Site blog

Anyone in the world

By EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Lisa Kalim

Following last summer’s military evacuation of families from

Afghanistan and a subsequent period in temporary hotel accommodation, many of

these refugees are now permanently settled in Hampshire. The families have been able to start the

process of building new lives for themselves.

For the children an important part of this has been starting school and

being able to attend regularly. This

blog describes the experiences of nine-year-old Maryam as she left Afghanistan and

how her new school in Basingstoke helped her to settle in and subsequently begin

to thrive.

Kabul

Maryam was airlifted by the British military from Kabul airport on the 26th of August 2021, together with her parents and two younger brothers. Her father had previously worked as an interpreter for the British army for several years and was therefore fearful that the whole family would become a target for the Taliban if they remained in Afghanistan.

The decision to leave their home was a sudden one. Maryam was woken in the middle of the night and told to put a few things into a small backpack. Shocked, she hastily packed a few clothes and a bottle of water, grabbed her favourite necklace and then they were picked up by a family friend who had a car. He drove them as close to the airport as he could get and then dropped them off – the roads close to the airport were all blocked by vehicles and large numbers of people on foot who were packed tightly together. It took Maryam and her family several hours to get near to the airport perimeter. By this time, it was starting to get light. Then they had to join the crush to get through the gate and try to work their way towards the front where soldiers were checking papers and making decisions about who could get a place on a flight and who would be left behind. It was incredibly difficult to move forwards because there were so many people and there was no space to move. Maryam was terrified that she would be separated from her family and never find them again. They gradually inched their way forwards, managing to stay together, but many more hours passed and they were still nowhere near the front. It was really hot and there was no shade. They hadn’t brought any food with them, so they were all hungry. There were no toilets. They spent the rest of the day in the crush and into the following evening. Just as it was starting to get dark, there was a loud explosion behind them and they could see smoke rising from just outside the airport close to where they had been earlier. This was shortly followed by the sound of ambulance sirens. Maryam felt numb inside – what was happening to her didn’t seem real, she felt like she was in a movie.

Eventually, sometime in the night, they reached the front. Maryam watched as her father waved his papers at the soldiers, desperately trying to get their attention. He had to keep trying for quite a while but at last a soldier took his papers, examined them and then let the whole family through. They were taken to a runway where they had to wait for several more hours before boarding a military plane. Once they were aboard Maryam quickly fell asleep only waking when the plane touched down in the UK.

Once they had left the plane, they were told to get on a bus that was waiting for them just outside the airport. Maryam had no idea where they were going. She looked out of the window and found that everything looked very different to what she was used to. She was not sure if she was going to like living in England.

Basingstoke

Three months later Maryam and her family were finally able to move from their temporary hotel room to their permanent accommodation in Basingstoke. It was such a relief to be out of the hotel and to have their own safe space at last. For the first time in her life Maryam had a bedroom to herself. She was delighted to discover that it even had a small desk and a chair that she could use to study at home. It had been several years since Maryam had been able to attend school in Afghanistan due to it being too dangerous – the Taliban often targeted girls’ schools as they did not support education for girls or women. There had been many attacks aimed at schools where bombs had exploded resulting in children being injured or killed in the province that Maryam’s family came from. Her father had reluctantly decided that it was safer to keep Maryam at home. He tried his best to continue her education by teaching her at home when he was not working but this was not possible every day. In fact, Maryam was one of the lucky ones in terms of being able to access at least some education as about 40% of children in Afghanistan are not able to attend school at all.

Shortly after moving into her new home Maryam was hugely excited to find out that she had been given a school place at her local primary school. She had walked past it a few times on the way to the shops so knew what it looked like on the outside but had no idea what it would be like inside or what kind of lessons she would have. Then she started to worry about how she would understand what her teacher was saying because she didn’t know much English. Her father told her that they had been invited in to speak to school staff and that she would find out more then. He said that he was sure that they would do everything they could to help her and that she should try not to worry.

A few days later Maryam and her father visited her new school. They had a good look around the whole school with Maryam’s father acting as an interpreter so that Maryam could understand everything that was being said. Maryam was amazed at how different it was compared to her old school in Afghanistan. The classrooms themselves were much bigger and there were only about 30 children in each class. She had been used to smaller classroom sizes with up to about 60 children in each, packed in very close together. There were no individual desks – instead the children sat in groups around tables. Maryam was puzzled to see that not all of them faced the front. There were lots of pictures and children’s work on the walls – this made it seem much brighter and more colourful than what she was used to. All the classrooms had large electronic screens on the walls at the front and Maryam saw teachers using these to show their pupils lots of different things – back in Afghanistan her teachers had just had a board at the front that they wrote on, and the pupils had to copy what they wrote into their exercise books. Maryam didn’t see this happening here and wondered how she would know what her teacher wanted her to do. Another strange thing that she noticed was that for quite a lot of the time the children were talking amongst themselves whilst doing some writing in class – this would not have been allowed in Afghanistan and if you were caught talking, you would be punished.

Maryam was introduced to her teacher and was told which classroom would be hers. The teacher explained what Maryam would need to bring to school each day and where she could hang her coat and bag. She also showed her where to line up in the morning and told what time she had to be there and when school finished. Maryam was surprised that the school day was so long in Basingstoke – back in Afghanistan her school day had only been about three and a half hours long with another shift of children arriving in the afternoon. However, she felt reassured that she knew what to expect. Most importantly she had also been shown where the toilets were as she had been worrying about not being able to ask about this. Maryam was also introduced to a girl called Isobel who was going to be her ‘buddy’ on her first day. She seemed very friendly, and Maryam felt happier knowing that she wouldn’t be left on her own.

The next day Maryam started at her new school. She felt a strange mixture of excitement and nervousness but visiting the school the day before had helped her to feel less worried than she would have been if she hadn’t already had the opportunity to visit the school.

Unbeknown to her the school had been busy preparing for her arrival. They had identified some actions that they could take and strategies that they could use to best support Maryam as she started her full-time education in the UK. They ensured that Maryam was placed in her correct chronological year group, Year 5, and her teacher made sure that she was included in the same types of activities that the other children were doing in class, but with appropriate differentiation and lots of peer support. She was placed in a middle ability group with children who would be able to assist her if needed and who could provide her with good models of English. They understood that withdrawing her from the classroom for interventions or to ‘teach her English’ would not be a helpful approach and that what she needed was to follow ‘normal’ school routines as far as possible. They were also very mindful that Maryam had been through a very traumatic experience in the way she left Afghanistan. She had also had to leave almost everything behind in terms of possessions, extended family and friends at very short notice to move to an unfamiliar country where her family knew no-one. Because of this, the school decided that initially their focus should be on providing excellent pastoral care, ensuring that Maryam settled into the school well and was happy rather than concentrating on her academic attainment and progress (which could be addressed later).

The school also considered cultural differences and how these might affect Maryam at school. One area where they felt this could be relevant was around the school’s PE kit and changing facilities. Mindful that Maryam would most likely not feel comfortable changing for PE in front of boys they ensured that she had a private area in which to change and also allowed her to wear long track suit trousers instead of shorts for PE.

The school was also very aware of the importance of finding out as much as possible about Maryam’s background including details of her previous schooling and her skills in her first language, Pashto. The school therefore put in a referral to EMTAS soon after Maryam joined the school so that profiling could be carried out. They also kept in regular contact with Maryam’s father to ensure that there was good home-school communication.

It’s still early days in terms of how long Maryam has been in school in the UK but the early signs are good. She seems to have settled and is joining in with class activities non-verbally. Her teacher has high expectations of her going forward. Her father reports that although she is finding school very tiring, she is enjoying attending.

Hampshire EMTAS have advice and guidance about refugees and

asylum seekers on our website here. We have also produced a comprehensive good

practice guide which schools receiving refugees and asylum

seekers in Hampshire will find useful. There are more resources on our Moodle.

[ Modified: Tuesday, 25 January 2022, 11:18 AM ]

Comments

Anyone in the world

In this blog, Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Jamie Earnshaw explores best practice provision in relation to the placement of learners with EAL in 'ability' groups, sets or streams in primary and secondary school settings.

Typically, any decisions on which group, set or stream to place

learners in are based on their perceived academic ability. If learners with EAL are placed in

groups, sets or streams merely according to their proficiency in English, or

what they can demonstrate in English, it might take some learners many years

before being able to access appropriately cognitively challenging tasks in the

upper groups, sets or streams, given the timescales involved in learners

reaching a similar level of English to their monolingual peers. For example, generally

speaking, younger learners who start to learn English in Key Stage 1 can take

between 7 and 10 years to acquire full cognitive academic language proficiency

(CALP) in their use of English across the curriculum. Older learners with

better developed language and literacy skills in their first languages may take

between 5 and 7 years to achieve CALP.

It is vital to

keep in mind that a learner’s proficiency in English is not necessarily representative

of their cognitive ability and of their understanding of subjects or topics if

demonstrated in their first language (L1). Schools should therefore make any

decisions to group, set or stream learners on a multitude of factors, not

solely based on a learner’s level of proficiency in English, keeping in mind

that a newly arrived learner of EAL is unlikely to have a sufficient level of

English to demonstrate their full knowledge or abilities.

Therefore, when

assessing learners with EAL, and consequently when making any decisions

relating to the placement of learners in groups, sets or streams, schools

should collect a range of information, including their prior education and

skills in L1.

With

this principle in mind, standardised tests should be avoided for early stage

learners of EAL and results from such tests should not be used to inform the

placement of learners with EAL into groups, sets or streams.

Why should L1 help to inform decisions on the placement of learners with EAL?

Research by

Cummins (1984, 1996)[i]

highlights the interdependency of a pupil’s academic skills in L1 and a second

language – known as common underlying proficiency.

Later research

suggests:

‘This common

underlying proficiency allows some aspects of cognitive/academic or

literacy-related skills to transfer across languages, including: conceptual

knowledge, subject matter knowledge, higher-order thinking skills, reading

strategies and writing composition skills’[ii]

It might

therefore be the case that a learner understands ideas or concepts in L1,

including those which are more abstract and complex, and is confidently able to

demonstrate this understanding in L1. However, when asked to demonstrate their

understanding in English, they might lack the necessary language of instruction

to fully understand the task they are being asked to complete, or, equally,

they might not have a sufficient command of English vocabulary or language

structures to be able to convey their understanding to school staff or peers,

who do not share the same language medium.

Appropriate

assessment of a learner with EAL will help to provide a more accurate

determination of a learner’s existing knowledge and skillset, rather than

merely what they are able to demonstrate through the medium of spoken or

written English.

The importance of appropriate placement of learners with EAL

Research

highlights the fundamental fact that all learners achieve more when they view

the learning environment as positive and supportive[iii]

and therefore, any decisions on groups, sets and streams should look to

facilitate the appropriate level of cognitive demand for the individual

learner. This is pivotal in ensuring the positive learning journey of learners

with EAL and in supporting their progression to developing full CALP.

Furthermore,

a key part of language learning is having access to a range of strong written

and verbal models of English, which is most likely to be found in higher

ability groups, sets or streams. This should be a fundamental consideration

when making decisions on the placement of learners with EAL.

The Bell Foundation research highlights how it ‘seems as though EAL learners are too often considered to be ‘learning disabled’ and/or classified as SEN[D] rather than simply being less proficient in English’.[iv]

The

distinction between EAL and SEND is explicitly stated in the Children and

Families Act 2014, section 20 (4):

‘A

child or young person does not have a learning difficulty or disability solely

because the language (or form of language) in which he or she is or will be

taught is different from a language (or form of language) which is or has been

spoken at home.’

Indeed,

learners with EAL are no more likely to have SEND than any other learner. Learners

with EAL should not therefore be automatically placed in lower sets with SEND

learners.

Learners

with EAL, like their monolingual peers, generally understand the principles

around placement of learners in groups, sets or streams and are therefore aware

that they are grouped with peers of a similar academic ability. By

inappropriately placing a learner with EAL with other learners who are of low

underlying cognitive ability or who have SEND, it is likely to be demeaning and

demotivating for them. Indeed, according to research from The Bell Foundation,

where learners were ‘not fully stretched because of insufficient staff

assessment and knowledge of their prior learning and attainment, their motivation

levels dropped and their behaviour in school could deteriorate’. i[v]

Furthermore,

it is important that the activities and tasks offered to learners with EAL are

appropriate for their cognitive ability. Thus, for example, offering a reading

task to a pupil with EAL from a storybook that is well below their age may be

counter-productive because although the language demand may be lower, the

images and concepts may be inappropriate and serve to demean rather than help.

Tasks for learners with EAL should be cognitively challenging and language is

best acquired when there is a clear context within which the pupil is learning

the target language.

With

this in mind, back-yearing or deceleration, where learners are placed in a year

group below their chronological age, should, in the vast majority of cases, be

avoided.

What if a learner with EAL does not have prior knowledge or understanding in a particular subject area?

The

principle that a pupil’s proficiency in English will increase more quickly

alongside accurate, fluent users of English, providing positive models for both

language and behaviour, is widely accepted.

According

to research from the DfE:

‘It

is … vital that pupils learning English have the opportunity to hear positive language

models, and so groupings need to be managed carefully to ensure that this

happens’[vi]

Schools

should therefore keep in mind, even where it is determined that a learner with

EAL lacks sufficient knowledge or skills more generally in a specific subject

area, their placement in a group, set or stream should facilitate their access

to positive language models. The placement of a learner with EAL in a mid to

higher ability group is more likely to provide the range of opportunities to

hear and see language being modelled appropriately - a vital part of language

learning.

Conclusion

Fundamentally, the proper and accurate assessment of learners with

EAL, to determine their academic proficiency beyond what they are able to

demonstrate in English, is vital. Furthermore, when placing learners with EAL

in groups, sets or streams, the need for access to appropriate models of

written and verbal English, which underlines language learning, should be at

the forefront of any such decisions.

Recommendations

1.) Place learners with EAL in groups, sets

or streams which facilitate access to a range of positive models of written and

verbal English. This is a fundamental principle of language learning.

2.) Use accurate and appropriate individual

assessment of learners’ academic and cognitive ability, including through L1,

to inform decisions on their placement in groups, sets or streams.

3.) As part of the assessment process,

collate as much information as possible about learners with EAL, including

proficiency in L1, prior educational experiences and pedagogical approaches

learners are familiar with.

4.) Involve learners and their

parents/carers in the decision-making process as much as possible. Seek the

views of learners and provide regular opportunities for review. Be prepared to

explain any decisions to parents/carers and provide opportunities for them to

ask any questions they might have.

5.) Avoid automatically placing learners

with EAL in groups, sets or streams purely because there are additional adults

available to support. This is only likely to be beneficial if staff have

received specific EAL-focused language learning training.

6.) Avoid relying on the results of

standardised tests to inform the placement of learners with EAL in groups, sets

or streams.

7.) Ensure regular monitoring and tracking

of learners with EAL and provide regular opportunities for reviewing the

groups, sets or streams of learners with EAL.

8.) Promote the use of a learner’s L1 in

school to help with access to the curriculum. Training from EMTAS could help

staff to identify how learners with EAL could use L1 effectively in school

settings.

9.) Recognise the difference between the

needs of, and appropriate support for, a pupil with SEND, with that of an EAL learner

without SEND.

10.)

Do

not backyear or decelerate learners with EAL as a matter of course. This will

only be appropriate in a limited number of cases and should only be done in

consultation with Hampshire EMTAS so that the full range of factors of any such

decision can be considered.

11.)

Provide

opportunities for learners with EAL to have access to peers who can model

language and skills in an appropriate way. This will also facilitate

opportunities for learners with EAL to practise using the target language in

meaningful contexts. Ensure that EAL learners’ peers are trained effectively to

support them in this way.

12.) Be wary of using KS2 SATs

outcomes for learners with EAL in order to determine sets, groups or streams at

KS3. Learners of EAL, particularly those who joined a UK school for the

first time during Key Stage 2, may have suppressed KS2 results due to not

having had enough time to fully ‘catch up’ with their monolingual peers. Any algorithm that generates end of KS4 predictions based on KS2 SATs results,

or any setting decisions based on those suppressed KS2 SATs outcomes, may lower

teacher expectations of what that learner may be able to achieve given a

further 5 years’ education in the UK system.

Contact emtas@hants.gov.uk for further support and guidance. One

of our Specialist Teacher Advisors will be able to provide further advice for

specific cases.

Further reading

[i] Cummins, J. (1984) Bilingualism

and Special Education: Issues in Assessment and Pedagogy. Clevedon:

Multilingual Matters. ISBN: 0-905028-13-9

Cummins,

J. (1996) Knowledge, Power, and Identity in Teaching English as a Second

Language. In Genesee, F. (Ed.) Educating Second Language Children: The

Whole Child, the Whole Curriculum, the Whole Community. Cambridge University

Press. ISBN: 0-521-45797-1

[ii] Rosamond, S. et

al.(2003) Distinguishing the Difference: SEN or EAL – an effective

step-by-step procedure for identifying the learning needs of EAL pupils causing

concern. Birmingham Advisory Support Service, Birmingham City Council

[iii] Dorman, J.P.,

Aldridge, J.M. & Fraser, B.J. (2006) Using Students' Assessment of

Classroom Environment to Develop a Typology of Secondary School Classrooms.

International Education Journal, 7(7), 906-915

[iv] The Bell Foundation

(2015) School Approaches to the Education of EAL Students: Language

Development, Social Integration and Achievement

[v] The Bell Foundation

(2015) School Approaches to the Education of EAL Students: Language

Development, Social Integration and Achievement

[vi] Department for

Education and Skills (2002) Access

and engagement in ICT: teaching pupils for whom English is an additional

language

Read the

Hampshire EMTAS Position Statement on the placement of learners with EAL in

groups, sets or streams on our Moodle here.

For further

information on assessment of learners with EAL, see the section on assessment

in our Guidance Library here. Also, see our e-learning module on assessing L1 here.

See the

Hampshire EMTAS guidance on Standardised testing and EAL learners.

For

further information on back-yearing/deceleration, please see the full Hampshire EMTAS guidance on deceleration

for learners of English as an Additional Language.

Further

guidance on the distinction between EAL and SEND can be found on the Hampshire EMTAS

website here.

[ Modified: Tuesday, 11 January 2022, 9:52 AM ]

Comments

Anyone in the world

By Steve Clark, Hampshire EMTAS Teaching Assistant for Travellers

Hampshire EMTAS is pleased to announce the release of a new e-learning module for all school staff who support children and families from GRT backgrounds. This module - which complements existing EMTAS cultural awareness training - aims to offer CPD in a way, and at a time, which fits in with practitioners’ busy work schedules. It offers an insight, through self-driven exploration, into the linguistic and cultural aspects of several GRT backgrounds. There are phase-specific examples of how best to support children and families from GRT heritages and an opportunity to build an action plan to support your work with your GRT communities.

So what does it look like?

The GRT e-learning course takes approximately 40 minutes to complete. The objective is to provide a general awareness of several GRT cultural groups, their languages, their history and from where these groups originated. It is designed to enable the learner to explore various aspects to the support offered by a school to its GRT pupils and their families.

Who should take this course?

This unit will be relevant for class teachers, Governors, TAs/LSAs, the GRT coordinator and any home-school link workers. It is particularly relevant for any trainee teachers and those at an early stage in their teaching career. It is also a useful addition to the training programme of any agency that supports children and families from GRT backgrounds, whether they are within or outside of Hampshire.

What does it include?

Find out interesting facts about GRT cultures around the

world and listen to four podcasts about Roma, Irish Travellers, English Gypsies

and Showmen. In addition, you can have a try at a language activity which will

introduce you to Romany. There are interactive school maps where you can access

phase specific information about catering for GRT families. You can learn more

about the benefit of ascription for GRT pupils, their families and the school

and there is helpful advice about attendance issues, dual registration,

distance learning and how and when to use the ‘T’ Code appropriately. The unit

culminates with the creation of an action plan to support your role as GRT Lead.

How can I access this module?

This module is available free of charge to Hampshire LEA schools and Academies that have bought into the Hampshire EMTAS SLA. There is a charge for other institutions to access the unit. Please contact emtas@hants.gov.uk for details.

Where can I find out more about GRT?

Visit our website and use the tabs to find out more about GRT resources, how to access support for a Traveller child, effective distance learning for GRT pupils, the GRT Excellence Award and Kushti Careers

Guidance for schools regarding attendance

A Study Into the Use of the T Code

Find out more about our suite of e-learning

modules, including The Culturally Inclusive School

[ Modified: Tuesday, 4 January 2022, 12:14 PM ]

Comments

Anyone in the world

Starting school can be a tricky time for any child and their family but for learners of English as an additional language (EAL) it can be a particularly anxious time. In this blog Specialist Teacher Advisor Helen Smith discusses ways to support new EAL learners and help them and their families settle into the school community.

It can be difficult for some EAL parents to understand the equipment that their child needs for school, such as a P.E. kit, book bag and spare clothes. They may also welcome some guidance on what is appropriate and usual to put in a lunch box. Some parents may not be aware that their child needs to be able to dress themselves, take themselves to the toilet, feed themselves etc., and they will need some support with helping their child become more independent with their self-care. Families may also not fully understand the school system. In some countries for instance, children do not progress from one school year to the next without passing exams. Some parents may not be familiar with the concept of learning through play and will need help to understand all the learning that is taking place in a busy Reception classroom. In many counties their child would not be expected to start school until they are 6 or 7 years old. This can make parents feel more unsettled and worried about their child beginning their school journey at a young age.

There are some simple steps that you can take to help your

EAL families feel welcome and more settled. This starts with finding out as much background information as you can.

As

well as the usual new starter information, it will be useful to know about all

the languages spoken in the home. You

will need to ensure names are pronounced correctly and that naming

conventions are understood. It is also important to know if the child was born in the UK or if they’re

a new arrival to the country. If the child is not UK born, try to find out

about the circumstances of their relocation and about their journey – was it

difficult or traumatic? It is also useful to find out if the family is isolated

or if they have strong family and community links.

All this information will help you in putting the right support and resources in place. For example, you may like to share translated or simplified information available on our website. You can also direct parents to the EMTAS phonelines or ask a Bilingual Assistant to help interpret. An effective way to ensure good communication is to hold weekly/half-termly drop-in sessions for EAL parents to discuss any letters or concerns.

Tapping into children’s languages will help EAL learners feel

welcomed and settled in the classroom right from the start. You may consider using

a peer mentoring programme such as the

Young Interpreter Scheme or source multilingual signs and labels as

well as multilingual books and resources. You can also invite speakers of other

languages into your classroom and learn basic words in a child’s first

language. The use of first language should also be encouraged in play and the

rehearsing of speech and writing. Head to our

Moodle to find out how the use of first language as a tool for

learning can support your learners in making solid academic progress.

Another effective tool to help a child transition in school are Persona Dolls. They can be used to introduce a new member of the class and learn about other cultures but also to help children to learn ways to challenge unfairness and discrimination. They help with emotional wellbeing and self-esteem, highlight diversity and commonality and are also a great tool to encourage talk in the classroom. It is important to remember that the doll is a member of your class, not a toy. Persona Dolls can be borrowed from our Resources Centre and training on their effective use is available from EMTAS. Please contact the EMTAS office - EMTAS@hants.gov.uk - if you would like to book a session.

EMTAS Coffee Events revamped

Hosting an EMTAS Coffee Event is another way to help EAL families feel settled and welcome in school. The aim of a coffee event is to provide parents of EAL learners the opportunity to find out a little bit more about the routines and expectations of their children’s school and help them to feel more engaged with their child’s learning and the school community. It is good practice for one or two Bilingual Assistants representing the school’s most prevalent languages to be on hand to interpret as needed.

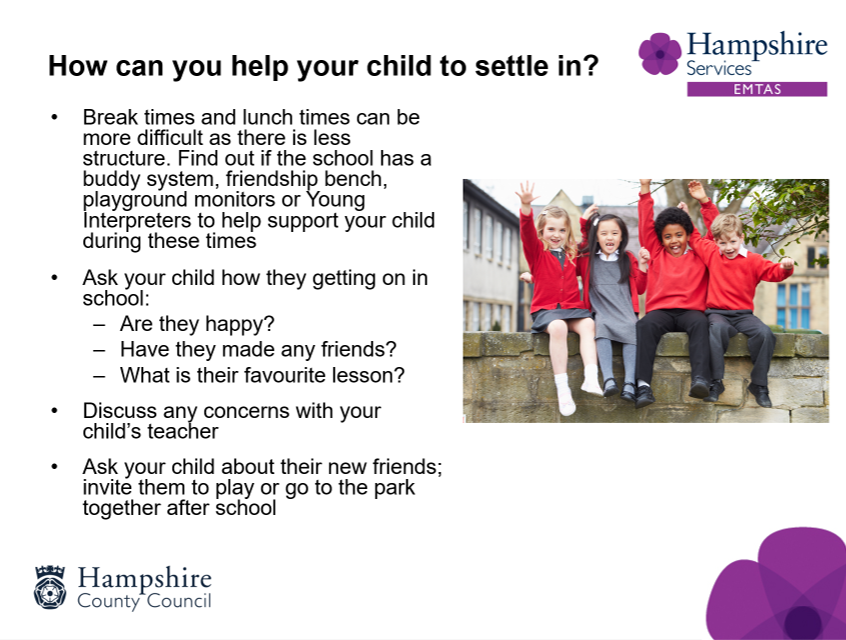

During the summer term we began a shake-up of our EMTAS Coffee Events programme. After all the lockdowns we felt that a lot of schools and parents would welcome the opportunity to get together face-to-face once again and start building partnerships. The sessions involve a suite of slides that can be adapted to suit the individual needs of the school. To ensure that we cater for all the languages spoken by our families, the coffee events and slides are designed to be simple, visual and informative. Coffee events are interactive and allow the parents ample opportunity to ask questions and voice any concerns or worries. To facilitate this, we have designed the slides to be based around questions, so it is more of a conversation than a presentation. Questions covered in the slides so far include:

What is Hampshire EMTAS?

What does my child need to be able to do for him/herself?

How can you help your child to settle in?

What does my child need to bring to school each day?

What should I put in my child’s lunchbox?

Should my child maintain first language?

How can you support your child’s reading?

What can you do at home to support your child’s learning?

Currently our slides our very Primary based. However we are working with Secondary schools to develop some secondary based slides. If you would like to book a coffee event for your school, you can contact the EMTAS office - EMTAS@hants.gov.uk.

More advice and guidance can be found on our

website. This includes information about making a Year R referral

and how and when to make a Year R transition referral. In addition more ideas

and resources can be found in the guidance library on our

Moodle. If you

would like to improve your EAL practice in Early Years you can also sign up for

our EYFS E-Learning on our Moodle. The course takes you through an introduction

and gives you some starting points and some context about the different

languages that are spoken across Hampshire. There are top tips and help with

assessment and action planning as well as advice on the best use of resources.

[ Modified: Friday, 7 January 2022, 4:27 PM ]

Comments

Anyone in the world

In this blog, the Hampshire EMTAS Teacher Team considers what best practice might look like in relation to catering for the needs of refugee children on roll in Hampshire Schools.

In recent months, Hampshire has hosted a number of refugee families from Afghanistan, some of whom will remain in the county permanently whilst others will eventually be found a permanent home elsewhere. The children of these refugee families are starting to be taken onto roll at schools across the county, and this has raised a number of questions as colleagues have sought advice on how best to streamline support at this vital point in the children’s lives.

First and foremost, at the point of referral to EMTAS it has become apparent that not everyone is confident when it comes to telling the difference between an asylum seeker and a refugee. To cut to the chase, the term refugee is widely used to describe displaced people all over the world but legally in the UK a person is a refugee only when the Home Office has accepted their asylum claim. While a person is waiting for a decision on their claim, he or she is called an asylum seeker. Some asylum seekers will later become refugees if their claims for asylum are successful.

The recently-arrived Afghan refugee children are here with their families and because of this they benefit from greater continuity in terms of support from their primary care-givers. Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children (UASC), on the other hand, are minors who are here on their own and therefore don’t have the support of their close families. UASC are accommodated in the care system in the UK but their status in the longer term remains in question. They will be claiming asylum, which – if they are successful – will give them indefinite leave to remain and refugee status. This will give them the right to live permanently in the UK and to pursue higher education and/or work in the UK. Check the EMTAS guidance for more detail on this point.

Moving on to talk about refugees, in many ways the needs of

refugee children are very similar to those of any other international new

arrival, hence staff in schools should, in the main, adopt the same EAL good

practice with these children as they would any others. There are, however, some additional things to

bear in mind.

Refugee children (as well as UASC) may have had to leave their country of origin suddenly, bringing with them very few of their personal belongings and leaving much behind. Because of this, some may experience a greater sense of loss than children whose move to the UK was undertaken in a more planned way. Some refugee children will have left behind members of their extended families as well as friends, favourite toys and pets (where keeping pets is part of their culture), and may be concerned for their safety or not know their whereabouts or even if they are alive. This can be compounded by having little opportunity to communicate with them to check if they’re OK. Older children are likely to be more aware of and affected by this than younger ones, and their awareness may be heightened by conversations within their household as parents talk about and begin to process the events that brought them here.

Some refugee children will have experienced unplanned interruptions to their education, especially those who have spent time in refugee camps en route to the UK or those who have travelled with their families through various countries. Lack of facilities might mean that some have missed opportunities to keep up with their learning, hence there may be gaps. The longer the gap, the more they will have missed – hardly rocket science, but something to bear in mind when thinking about reasons why a child’s reading and writing skills may not be as secure as would normally be expected. The advice with this would be to clarify each child’s education history with parents and then to consider what arrangements might be put in place to help plug any gaps – without causing them to miss even more eg through ill-timed/too many withdrawal interventions (see EMTAS Position Statement on Withdrawal Provision for learners of EAL).

For most refugee children, routine really helps. They benefit from knowing what each school day will hold, so things like visual timetables are helpful. They also benefit from being supported to quickly develop a sense of belonging in their new school. Use buddies – including trained Young Interpreters – to support them as they adjust to their new surroundings. Bear in mind that the less-structured times such as break and lunch times can be more difficult for a newly-arrived refugee child, so check that they are being included and are joining in with play with other children. Teachers may find it helpful to teach some playground games in the relative safety and calm of the classroom, with input and support from other children in their class, with the idea that these games can then transfer to the outside areas.

Support from their peers will be key to the induction and integration of a newly-arrived refugee child. Sit them with peers who can be good learning, behaviour and language role models. Try to match them with peers who are of similar cognitive ability. Remember to reward all children involved with praise where things have gone well eg if they have shown the new arrival their book or repeated an instruction or the new arrival has accepted support from a peer or tried to involve themselves in a task or whatever. With younger learners, consider using a Persona Doll to explore ways of supporting the new arrival with your class.

When it comes to accessing the curriculum, remember the benefits of using first language both to aid access and engagement and to give the child a sense of the value of the L1 skills they bring with them. Use of L1 can be a great way of involving parents too, so make sure you think of ways they can support – perhaps helping their child look up key words or using Wikipedia in other languages to research a topic. If you have a literate child in your class, encourage them to write in L1 and explore how translation tools can be used to build a dialogue with the child and give them the skills to communicate their ideas with others in accessible ways. Many translation tools have an audio component too, so even children who can’t read very well in L1 can benefit from their use in the classroom. For more information about translation tools, see ‘Use of ICT’ on the EMTAS Moodle.

The biggest issues often relate not to language barriers but to culture; there are lots of things we take for granted to be commonly understood, shared experiences which for refugee children will be new, alien. These can include experiences of teaching and learning, for instance a didactic approach wherein the teacher conveys knowledge to the empty vessels that are their charges may have been the norm in country of origin. People whose schooling embodied this sort of approach may find learning through play or learning through engaging in dialogue with others very ‘foreign’; uncomfortably new territory they need to negotiate without any prior experience on which to base their understanding or response.

Refugee children from Afghanistan will almost invariably be Muslim and this in itself raises some issues that schools will need to address. For some children, there will be issues with school uniform, with others, schools may need to rethink key texts they are using in class eg ‘The Three Little Pigs’ with younger learners or ‘Lord of the Flies’ with children in secondary phase may be problematic. For guidance on these and other issues to do with having Muslim children on roll in your school, see the comprehensive guidance from the Muslim Council of Britain (MCB), posted in an open access course on the EMTAS Moodle here.

So to some final advice on how to negotiate this unfamiliar terrain. For one, try to remember always that refugee children’s responses may at first seem strange or oppositional or even rude. This sort of thing is likely to be indicative of a cultural barrier that needs to be overcome with both parties open to moving their respective positions. To get the best results, try to be the party that is receptive to difference and willing to make the most moves to understand and accommodate. If issues arise and you’re not sure what to do, EMTAS is here to support so do get in touch with us.

By phone 03707 794222

By email emtas@hants.gov.uk

Find out more:

[ Modified: Tuesday, 11 January 2022, 2:53 PM ]

Comments

Anyone in the world

Part-time PhD student Sarah Coles is currently researching UK-born children’s lived experiences of growing up in more than one language. In this blog, she considers the place of the home language in the linguistic landscape of bilingual children from linguistic minority communities.

My research focuses on the development

of both first language (L1) and English (L2) of bilingual children growing up

as members of linguistic minority communities in an L2 context. It’s a longitudinal study that follows a

small sample of bilingual children through their first year of schooling. Using picture sequences, I elicit stories

from each child, one in L1 and another in English, their L2. This will be done once at the beginning of

the fieldwork phase and again at the end.

In this way, I hope to be able to identify how the children’s two

languages evolve over time and to document any shift in dominance from one

language to another that may occur. I

will also work with each child to explore their lived experiences of growing up

in two languages. Additional contextual

information, including the detail of their own language use, will be gathered

from the children’s parents. Ultimately,

through the children’s own narratives, I hope to deepen practitioners’

understanding of bilingual children in the Foundation Stage and to pinpoint

some practical ways in which support for such children might be tailored to

improve their engagement with their learning.

Setting the scene: two

broad-brush models of bilingual development

Across the globe, monolingualism is not the norm for all

children; exposure to more than one language and bilingual development from an

early age is in fact more prevalent than a monolingual model. Children may experience different routes in

their journeys to bilingualism dependent on their immediate family contexts. Some children will be born into households

where each parent speaks a different language and the child has access to both

from birth. This might be described as simultaneous

bilingualism. Other families may be part

of a settled immigrant community and the child may experience a monolingual

start, being exposed to a minority language at home and, later in their

development, the majority language outside of it. This would describe sequential

bilingualism.

The outcomes for children growing

up in bilingual settings are varied. Some

will go on to develop comparable skills - receptive and productive – in their

two (or more) languages and will be able to function in different contexts –

school, home, community – equally well in both/all. At the other end of the spectrum, it is just

as possible for a child to have exposure to two (or more) languages yet to

learn to speak only one themselves.

The possible impact of differential linguistic prestige

There are various factors that may

influence the course and outcome of a bilingual child’s language

development. One that seems to be significant

relates to people’s perception of the relative prestige of the child’s two – or

more - languages. A child from a linguistic

minority community may experience a monolingual start to life with exposure to

the minority language in the home from their main care-givers from birth. Later, and because it is the language of

schooling, the child is required to develop a second, additional language,

English. For such a child, the second

language is where the cultural capital resides, it being the language of the majority

community. Because of its sociocultural

dominance over the minority language, it is often the case that this second

language becomes the child’s preferred one, eventually replacing their first,

minority language.

This is a scenario experienced by

many children of Hampshire’s UK-born ethnic and linguistic minority communities. They may, in their early years, be exposed to

– let’s say – Nepali at home but later, when they start school, English. From that point onwards, families may notice

their child gradually ceases to use Nepali, preferring to respond in English

even when addressed in first language (L1).

This end result is sometimes referred to as ‘passive bilingualism’

although as De Houwer (2009) notes there is “nothing passive about

understanding two languages and speaking one”.

The possible impact of quantity of input experienced

A second consideration is the quantity

of language input experienced by the child.

In a monolingual context, the language of the home is the same as the

language of the wider community and – often – of education too. Everywhere the child goes and everyone they

meet speaks the same language. Hence the

child has multiple models of the same, single language. In contrast, linguistic minority children born

in the UK may have exposure to L1 at home and L2 (English) outside of it. Hence their overall exposure to L1 is – in

most cases - reduced.

The impact of reduced exposure to

each of the bilingual child’s two languages has been explored by researchers

with an interest in child language development.

One thing that’s emerged is the observation that a child’s lexicon (the

words they know and use) in each of their languages reflects the amount of

exposure the child has to each language – which is typically less for each

language than the total exposure to their one language experienced by a

monolingual child of similar age. When

their vocabularies in both languages are combined, however, the overall picture

of these bilingual children’s lexical development has been found to be on a par

with their monolingual peers.

Further, research has identified

that if the words known by a bilingual child are listed, only about one third

represent words that are translations of each other; i.e. two thirds of the

words a bilingual child knows in one of their languages are known only in that

language and are not shared with the child’s other language. This is likely to be directly related to differences

in the contexts in which each language is used and the communicative purpose being

served.

The possible impact of context

Some researchers have found there to be discrepancies

between UK-born bilingual children’s skills in L1 (the heritage language)

compared with those of children of comparable age but growing up in a

monolingual context. They suggest that

the L1 skills of bilingual children growing up in the UK are unlikely to reach

a level comparable to monolingual children growing up in country of origin. This, they say, is largely due to reduced

exposure to the heritage language from adult L1 models who may themselves be

experiencing language loss due to lack of use.

The overall outcome, some have suggested, is likely to be ‘incomplete L1

acquisition’.

Elsewhere in the literature, the notion that ‘incomplete first language development’ exists at all attracts criticism. Some have argued that all intergenerational first language transmission, including that which takes place in monolingual settings, evidences change. According to this view, what others may see as ‘errors’ in L1 in fact represent “normal intergenerational language change accelerated by conditions of language contact” (Otheguy, 2016). According to this view, in immigrant populations new L1 norms will naturally develop, resulting in divergence between L1 use in an L2 immersion context compared with L1 use in a monolingual, home country context. Hence context has a bearing on the language models to which a bilingual child might be exposed.

The possible impact of the language modelled

Another important consideration when it comes to a child’s

language development is the nature of the language models to which they are

exposed. Typically, linguistic minority parents

themselves do not function in a monolingual context and this can have an impact

on their everyday language practices.

The result is often an incremental increase in both code-switching (characterised

by swapping from one language to another at word/phrase level) and code-mixing

(combining grammatical structures from both languages) where in their

speech they move in a fluid, natural way between languages, swapping a word or

a phrase here and borrowing a grammatical structure there.

In the literature, code-mixing and code-switching are identified

as common linguistic practices amongst bilingual populations. Having been found to be rule-based and

systematic, code-switching and code-mixing are these days viewed in a

favourable light as opposed to the deficit view that prevailed in the past that

stigmatised them as “…the haphazard embodiments of “language confusion”

(MacSwan, 2017).

Although limited in terms of the number of empirical studies into the impact on bilingual children’s language development of code-switching and code-mixing by their parents, research suggests that bilingual adults frequently engage in these practices in interactions with their children. This is in line with trends identified in the broader sweep of studies into bilingual code-switching and code-mixing. What it means for a child growing up in more than one language is that they are likely to experience code-switching and code-mixing in language inputs modelled by family members and other significant adults around them. This may in turn prompt them to code-switch and code-mix themselves in their own speech.

Code-switching and code-mixing in

parental inputs appear to influence L1 development in children growing up as

members of language minority communities in other ways too. Some studies have found a negative

correlation, with higher rates of code-switching and code-mixing by parents resulting

in lower comprehension and production vocabulary sizes in young children. Others have identified that code-switched

input, arguably more challenging to process than input in a single language,

has positive outcomes but only for those children with greater verbal working

memory capacity who are capable of processing it.

What this means for my research

To draw to a close, the above

whistle-stop tour illustrates that bilingual language development is a complex,

multi-faceted phenomenon. It is affected

by multiple influences, each impacting in different ways and to different

degrees on the individual child in their own specific context. Through my research, I make space for a small

sample of UK-born bilingual children to explore these differences and to focus

on their first-hand experiences of growing up in more than one language. Once this has happened, any findings relevant

to practitioners working with young, UK-born bilingual learners will be shared

so that all bilingual children in Hampshire schools and settings receive a Year

R experience that is sensitive to their developmental needs.

References

De Houwer, A. (2009). Bilingual

first language acquisition (1st ed., Vol. 2). Multilingual Matters.

MacSwan, J. (2017). A Multilingual Perspective on

Translanguaging. American educational research journal, 54(1), 167-201.

Otheguy, R. (2016). The linguistic competence of

second-generation bilinguals Romance linguistics 2013 : selected papers from the 43rd Linguistic Symposium on

Romance Languages (LSRL), New York,

17-19 April, 2013, New York.

[ Modified: Thursday, 14 October 2021, 11:07 AM ]

Comments

Anyone in the world

By Claire Barker

At

long last we bring you the good news that the EMTAS conference will take place

on 15th October 2021 at The Holiday Inn, Winchester. We

are delighted that this will be an in person event; over the last eighteen

months, the conference date has been moved several times because we really

wanted to be able to meet and greet you face to face. This is, at last,

possible and we look forward to welcoming practitioners who work in any phase

of education from EYFS to KS4 to the long-awaited event.

The

Conference is titled ‘All in this together – going from strength to

strength’. This reflects the post pandemic fatigue felt by many of us and

how we now need to move forward together to support our EAL and GRT children

who have maybe struggled with their education during the pandemic. Many

EAL and GRT children will have lost skills they’d acquired in English and will

now be playing catch up. Many will have missed out on peer-to-peer

interaction and the opportunities this provides to develop social language and

interpersonal skills. On the positive side, some will have improved their

first language skills as a result of spending more time living in that

language. Others will have increased their ICT skills and their digital

literacy and this will be a focus of one of our workshops, how to use ICT

programmes to support literacy in the classroom.

We are very fortunate to be able to welcome Eowyn Crisfield, who is a well know name in linguistic communities. Eowyn is a Canadian-educated specialist in languages across the curriculum, including EAL, home languages, bilingual and immersion education, super-diverse schools and translanguaging. Her focus is on equal access to learning and language development for all students, and on appropriate and effective professional development for teachers working with language learners. She is author of the recent book ‘Bilingual Families: A practical language planning guide (2021) and co-author of “Linguistic and Cultural Innovation in Schools: The Languages Challenge” (2018 with Jane Spiro). She is also a Senior Lecturer in TESOL at Oxford Brookes University.

Our very own Deputy Team Leader, Sarah Coles is currently studying for her PhD. Sarah’s longitudinal study, now in its fourth year, focuses on children with Nepali or Polish in their backgrounds. These two languages represent the greatest number of referrals made by schools to Hampshire EMTAS, hence the relevance of the research to the Hampshire context. In her presentation, Sarah will consider some of the features of the linguistic soundscape experienced by UK-born bilingual children. Drawing on findings from her pilot study, she will discuss the use of the Multilingual Assessment Instrument for Narratives, drawing attention to some points of note for mainstream practitioners with an interest in language development.

Our third keynote speaker of the day is Leanda Hawkins. Leanda is from a Hampshire Romany family with a long history of culture and heritage. She went on to Higher Education, and has carved a career supporting children with special educational needs. Her motivation is to help all children progress and thrive through education. Leanda will share her experiences of education as a child, student and artist now working as Behavioural Lead and HLTA in a federated school in Hampshire.

The workshop offer will include a session with Eowyn looking at 'Language and literacy development for multilingual learners: What do we know and what can we do?'. There will be an interactive IT session looking at OT programmes to support literacy in the classroom led by Lynne Chinnery. Jamie Earnshaw will lead a workshop focusing on the 'New Hampshire EMTAS first language support programmes'. Helen Smith will host a session on 'Literacy for GRT pupils and breaking barriers in the school community'. Sarah Coles will lead a session on ‘MAIN - Multi-Lingual Assessment Instrument for Narratives'.

The Conference promises to be exciting and informative. Delegates will have the opportunity to participate in two workshop sessions as well as time to visit the stalls that will promote and highlight resources to help support EAL and GRT students.

If you would like to continue your studies in EAL best practice the new Supporting English as an Additional Language(SEAL) course begins later this term. If you are interested in this course please contact HTLC to book a place or email: Claire.Barker@hants.gov.uk for more information.

We are looking forward to seeing you at our future events.

References

Language and learning loss: The evidence on children who use EAL (bell-foundation.org.uk)

Languages in lockdown: Time to think about multilingualism | LuCiD

[ Modified: Thursday, 7 October 2021, 1:21 PM ]

Comments

Anyone in the world

By the Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisors

Welcome to this new academic year. The EMTAS team is feeling refreshed after the summer holiday and looks forward to continuing their work. We’re particularly excited to support more schools this year as they work towards achieving an EAL or GRT Excellence Award. In this blog you will find out what’s in store for 2021-22 to support your professional development as well as your award submission. You will also learn more about our Heritage Honours Award, find out about staff changes in our team and catch up with important research projects.

Network meetings

The dates of our EAL network meetings can be found on our

website. We will also be holding

specific network meetings for Early Career Teachers, the details of which can

be found on the same page of our website. The termly GRT-focused network meetings will continue to be held

online this year. Like our EAL network meetings, they are free to

attend for Hampshire-maintained schools. To find out when the next ones

are, check the Training section of the EMTAS website.

EMTAS conference

We are very much looking forward to the EMTAS Conference on Friday 15th October at the Holiday Inn in Winchester. It promises to be an enlightening day with Eowyn Crisfield as one of our keynote speakers. She is an acclaimed expert in languages across the curriculum and has a wealth of knowledge in this field. Sarah Coles will be sharing her research findings on ‘Pathways to bilingualism: young children’s experiences of growing up in two languages’ and Leanda Hawkins will speak of her experiences of education from the perspective of belonging to the Romany community. There will also be a selection of cross phase workshops for delegates to take part in and stalls to see some of the latest resources available to support EAL and GRT pupils in education. Everyone who signs up will receive a free set of the latest EAL Conversation Cards valued at £45. There are limited spaces so please sign up as soon as possible. For further information and online booking please see our flyer attached to this blog.

New e-learning

We are pleased to announce that we have new E-learning modules now available:

- Supporting children and families from Gypsy, Roma and Traveller (GRT) backgrounds

- Developing culturally inclusive practice in Early Years settings

- The appropriate placement of learners with EAL in groups, sets and streams.

Our e-learning modules are free to access for Hampshire-maintained schools. To find out how to obtain a login, please see our Moodle.

Heritage Honours Award

The EMTAS Heritage Honours award, launched last academic year, celebrates the achievements of children from BME, EAL and GRT backgrounds at school and within the home/community. Children and young people can be nominated for an award by the school they are currently attending. More than 60 successful nominations were received last year. Reasons for nomination variously include success in heritage language examinations, practical and creative use of first language within the school environment, sharing cultural background with peers, acting as an empathetic peer buddy, success in community sporting events and excellent progress in learning EAL. Nominations are now open for this year. To find out more about how to nominate a pupil, see our Moodle.

Research

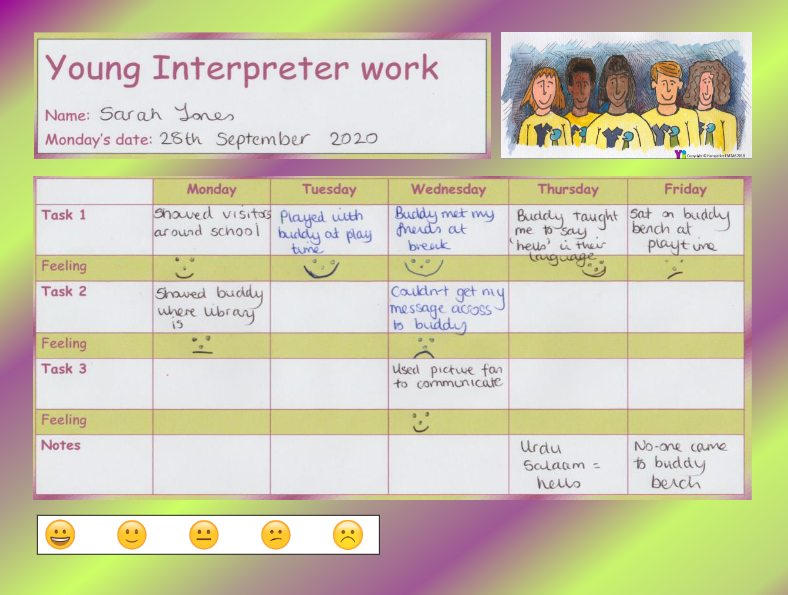

Debra Page is entering the third and final year of her PhD researching the Young Interpreter Scheme. Data

collection happened online due to the pandemic and the first and second wave of data collection with 84 children across 5 schools is now complete. The third and final data collection will be in November and all the data

will then be managed and analysed. In her last update, Debra shared a YI diary

and additional training resource she created. She delivered this virtually with

each school during their YI training session and initial feedback has been very positive. It is hoped that these extra resources will form part of the YI

training in the near future. The children are excited to complete their diaries

about the work that they do as a Young Interpreter. If the diary is something

that you are interested in, please get in touch. We look forward to finding out

results of what is learnt about the Young Interpreter Scheme.

Sarah Coles will update us on her own PhD in a separate blog very soon. Her PhD is part time and she’s just embarking on her fourth year of study. She’ll mainly be involved in data collection this year and a number of schools with children from Polish and Nepali families starting in Year R have agreed to support this. Sarah is hoping the families she and members of our Bilingual Assistant team approach will be similarly willing to be involved.

Staffing

At the end of last term, we wished Chris Pim a happy retirement and welcomed back Astrid Dinneen following her maternity leave. As a result, we have made some changes to the geographical areas the specialist teacher team will be covering:

Sarah Coles – Winchester

Lisa Kalim – New Forest

Astrid Dinneen – Basingstoke & Deane

Jamie Earnshaw – Eastleigh, Fareham and Gosport

Claire Barker – Hart, Rushmoor and East Hants

Lynne Chinnery – Havant, Waterlooville and Isle of Wight

Helen Smith – Test Valley

Sarah, Claire and Helen will also cover GRT work across the county.

We also welcome Abi Guler to our Bilingual Assistant team. He will be working with our Turkish families. We are delighted to have also newly recruited Fiona Calder as our new Black Children's Achievement Project Assistant.

We are all looking forward to continuing working with you. In the meantime, be sure to subscribe to the blog digest and visit our website.

[ Modified: Friday, 10 September 2021, 11:29 AM ]

Comments

Anyone in the world

By Hampshire EMTAS Traveller Teaching Assistant Steve Clark

The big leap from Year 6 to Year 7

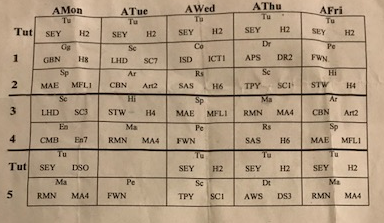

First steps into secondary school can be difficult for any pupil. Secondary schools are usually much bigger environments with more pupils and staff than most primary schools. The differences are noticeable: pupils move between lessons rather than staying in the same room all day and there is a complex school layout and timetables to negotiate. Pupils for whom English is an Additional Language (EAL) and pupils from a Gypsy, Roma, Traveller heritage (GRT) find the transition challenging. Rather than making the leap into the unknown, some GRT pupils withdraw from mainstream education and opt instead for elective home education (EHE).

This year more than any other year it will take a concerted effort from EAL and GRT children, parents, carers and schools to support their transition. The Coronavirus has led to a long absence from school for most pupils and many will find adjusting to the routines of the school day and entering a new learning environment particularly challenging.

Many EAL families may have experienced high levels of anxiety about Covid-19 and isolation especially where they have not been able to go and visit relatives or, in some cases, have any contact with them at all. Some families will have suffered bereavement and their children may benefit from bereavement counselling and/or ELSA support. EMTAS can also offer first language support for schools and families, mentoring for pupils and cultural advice for staff.

Many of our GRT families are fearful of the impact of the virus on their children and their communities and may be very reluctant to allow their children to return to school for this reason. If this is the case, schools can ask for EMTAS support for staff and the GRT communities affected.

Many GRT families are self-employed and due to the nature of their work may be experiencing high levels of anxiety due to the impact of the lockdown on their ability to continue working. Some families may be trying to off-set this by travelling further afield to secure work.

Hampshire EMTAS is, as always, ready to support all concerned with transition. Usually, we offer a transition programme for GRT pupils and EMTAS staff visit pupils in person to support and facilitate their journey from primary school into secondary. However, this year, because of social distancing, EMTAS staff are instead offering this support via telephone and can liaise with EAL and GRT parents and carers this way to answer any questions they may have and to support them with the transition. In October, after the child has started in their secondary school, an EMTAS member of staff will arrange a follow-up visit to see them to check they are settling in.

What EAL and GRT pupils, parents and carers may want to know

Lunch systems - Many schools are cashless and operate a fingerprint recognition system to pay for lunches. It is important to stress to GRT and EAL pupils and their families that their fingerprint will not be used for any other purpose.

Mobile phones - It is important to communicate to GRT and EAL pupils, parents and carers, the school’s expectations around the use of mobile phones during the school day and to clarify how they can contact each other in exceptional circumstances.

Homework - Starting a conversation between school staff and GRT and EAL pupils, parents and carers can prove highly effective in ensuring that any potential problems with completing homework are identified early on and flexible solutions found.

Uniform and equipment - It is recommended that schools have a full and clear conversation with GRT and EAL parents and carers prior to the child starting in Year 7 about what equipment the pupil will need and what is acceptable uniform including jewellery and hairstyle. This may give school staff an opportunity to address any concerns the family may have regarding cost.

Cultural factors should be considered e.g. clarification about the provision of separate changing facilities for PE and modesty -related issues to do with PE kits etc. These are particularly relevant to Muslim students and their families.

Religious observance - Sikh boys may wear a patka (head covering) or other hair covering and may, for religious reasons, not have their hair cut; hijabs may be worn by some Muslim girls. Many Muslim pupils, especially once they are in secondary phase, will observe fasting throughout Ramadan followed by Eid, a day they may request permission to take off school for religious observance.

Attendance - Communication between GRT and EAL pupils, parents, carers and school staff is vital to ensure a good level of attendance (96% or above) is maintained. Clear guidance should be given to GRT and EAL pupils and parents on how to report any absence. Maintaining a good relationship with the GRT and EAL families will help to continue the conversation and to help identify any problems with attendance.

Art, Design & Technology, Food Tech and Science – Discussions between school and parents and carers about funding and the supply of ingredients and materials for these subjects can help avoid any potential misunderstandings or disruption to the pupil’s learning.

Ideas for schools to build confidence from Day One in September

The better prepared a pupil is for their transition, the more smoothly it will go. It is a good idea for the primary school to show pupils a timetable from a secondary setting and explain to them what it means. If the secondary school can provide a digital tour of the school this year to help ease anxieties about what the new environment looks like, this would help pupils gain a little knowledge about what to expect to see on their first day. A short film introducing key staff and the Year 7 Tutor team would allow the pupils to recognise these people more readily.

Communication with EAL and GRT parents and carers in the next few weeks will help identify and hopefully answer any questions the child and parent may have.

Schools running the Young Interpreter Scheme or New Arrivals Ambassador Scheme will be able to guide pupils into supporting their peers’ transition into school.

Hopefully all our EAL and GRT children will transition successfully in September and settle back into the learning environment quickly, making new friends and picking up with old ones. Give them time to think and process as the language and pressures of a new setting may take time to build up their confidence and to participate.

For further advice and guidance please visit the Hampshire EMTAS website and the Guidance Library for EAL and GRT.

Also see our dedicated pages for:

- GRT Advice and Guidance

- EAL Advice and Guidance

- Distance Learning including Covid-19 advice and guidance

For further information please contact Sarah Coles at sarah.c.coles@hants.gov.uk or the EMTAS office at emtas@hants.gov.uk.

Subscribe to our Blog Digest (select EMTAS)

[ Modified: Monday, 29 June 2020, 9:19 AM ]

Comments

Anyone in the world

By Rights and Diversity Education (RADE) adviser Minnie Moore

The shocking images on our screens of the death of George Floyd have resonated across the globe and led to many protests and demands for change across all areas of society in addressing and challenging systemic racism which is being characterised as an insidious and pervasive pandemic affecting every institution.

In Hampshire, through our education services, we have strived for many years to address discrimination and prejudice and to promote positive attitudes to difference across all our school communities. We support practitioners to enable them to provide a truly inclusive culture in their settings and there are many opportunities that teachers can access to enable them to continue to reflect on and develop existing practice.

Hampshire schools are in the enviable position of having access to a Rights and Diversity Education centre crammed full of teaching and learning resources which enable practitioners to embed good quality diversity education right across the ethos, environment and curriculum in their schools.

“It is firmly embedded in our staff psyche to source our topics from the RADE Centre as it is a treasure trove of resources and information covering a range of issues associated with rights, diversity and community cohesion in the UK particularly.” Headteacher Hale Primary School

CPD opportunities include training on race equality, diversity, equality teaching, pupil voice, prejudicial behaviour and Rights Respecting education and are all available to book in a range of formats tailored to individual school requirements.

'It was a great session. One of the best training sessions I’ve had to do with school including insets in my own setting.” Assistant Head teacher,Tanners Brook Primary School

We have recently produced a Hampshire Toolkit to support schools in challenging and responding to prejudicial language and behaviour which includes a new tracking form, a pupil survey and a leaflet for parents and carers. This is available to download by clicking on this link (FREE to Hampshire schools, please get in touch for a password).

The Voice of our children and young people is key to informing the work we do to embed inclusive practice across our schools and they have been instrumental in promoting equality and challenging discrimination in their school settings.

The Equality and Rights Advocates (EARA) is a group of students from

secondary schools across the county who work collaboratively to promote equality

and child rights in their schools, based on the nine protected characteristics

of the Equality Act and the UNCRC. The group has recently expanded to include

primary age children and have been making their voices heard across a range of

different platforms across the county. For more information on the work they do please click on this link. We are always looking for new members so please give your

students the opportunity to get involved!

The Equality and Rights Advocates (EARA) is a group of students from

secondary schools across the county who work collaboratively to promote equality

and child rights in their schools, based on the nine protected characteristics

of the Equality Act and the UNCRC. The group has recently expanded to include

primary age children and have been making their voices heard across a range of

different platforms across the county. For more information on the work they do please click on this link. We are always looking for new members so please give your

students the opportunity to get involved!

For more information on any of the above please contact Minnie.moore@hants.gov.uk.

Visit RADE's website

Contact RADE: Rade.centre@hants.gov.uk

[ Modified: Tuesday, 16 June 2020, 3:43 PM ]