Site blog

By Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Jamie Earnshaw

A huge congratulations to all students who achieved a GCSE in a Heritage Language this summer! EMTAS supported 48 students with GCSEs in Arabic, Chinese Mandarin, German, Greek, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Russian and Turkish.

Here are all the fantastic results

achieved by students we supported:

GCSEs graded 9-4

|

Language |

9 |

8 |

7 |

6 |

5 |

4 |

|

Arabic |

2 |

1 | ||||

|

German |

1 |

|||||

|

Greek |

1 |

1 |

||||

|

Italian |

4 |

3 |

||||

|

Mandarin |

3 |

1 |

||||

|

Polish |

7 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Russian |

2 |

1 |

2 |

|

||

|

Total |

18 |

9 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

GCSEs graded A*-C

|

Language |

A* |

A |

B |

C |

|

Portuguese |

2 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

|

Turkish |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Totals |

3 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

As you can see, students did extremely well this summer. Many students achieved the top grades and there were individual stories of success across the board too, including one student who did really well who was previously referred to EMTAS when in primary school and was later diagnosed with SEND with difficulties in reading and writing. Even with an uneven profile of skills across Reading, Writing, Speaking and Listening, with support and hard work, students can still succeed and achieve a grade at GCSE. Also do note that we offer an initial one session package of assessment to help determine if a student is ready for the GCSE.

Many of the students we supported this year were in Year 11 - we wish those students good luck with their next steps! No doubt the Heritage Language GCSE will be a bonus for those students to show to future colleges or employers. Do bear in mind though it is not necessary to wait until a student is in Year 11 to enter them for a Heritage Language GCSE but sometimes the themes of the exams are better-suited to older students (so perhaps most suitable for students in Year 9 onwards).

Visit

the GCSE page on our website for more information about the

GCSE packages of support we

offer to help prepare students for Heritage Language GCSEs. When you have

decided which package you want, ask your Exams Officer to complete the GCSE

Support Request and GCSE

Agreement forms and return them both to Rekha Gupta

using the address details provided on the GCSE Support Request form (by the

deadline of the 1st March 2020).

We look forward to working on Heritage Language GCSEs with you and your students this academic year!

Comments

Sarah Coles shares the fourth instalment of a journal-style account of her reading for the literature review and methodology chapters of her PhD thesis.

12th October 2018

Continuing with my reading, this time I write again about interviewing, as it seems there is no end to the number of articles devoted to this particular subject. I read one about interviewing dementia care-givers, a cheery little number. Whilst you might not immediately think there’d be many parallels, I found there was much to gain from it, mainly to do with thinking about respondent vulnerabilities, ethical considerations and how to get the most out of an interview situation when you are really expecting people to talk about some highly personal stuff to a someone they barely know. A lot of this boils down to knowing your interview schedule really well (that’s the list you prepare in advance of the key things you want to cover in the interview). It was found to be off-putting if the researcher had to refer to a list as this seemed to depersonalise the interview experience for respondents, causing them to stop giving full, descriptive accounts of their experiences – so clearly it had an impact that was entirely at odds with the researcher’s aims and as such is a useful tip I shall be taking on board. Also, and in a similar vein to guidance we are periodically given relating to dealing with safeguarding concerns and disclosures, it is advised that one avoids asking leading questions and instead asks people to describe their situations. O’Connell Davidson and Layder (1994) suggest that in qualitative approaches to interviewing, the researcher should be prepared to respond flexibly to whatever the respondent may say and should maintain a strong focus on listening and encouraging talk rather than on ensuring all the questions they have prepared are covered. Their book, ‘Methods, Sex and Madness’, is an entertaining caper through issues of gender identity, sexuality and witchcraft, all linked to research methods. I find it a refreshing change from the way research methods are discussed in more traditional academic writing, and it certainly raises some important points to ponder in relation to my own research. These points are reiterated by a guy called Seidman writing in 2013, who advises that in-depth, qualitative interviewing should have as its goal to encourage respondents to reconstruct and express their experiences and to describe their making of meaning, not to test hypotheses, gather answers to a set of pre-determined questions or corroborate opinions. Seidman goes on to expend some wordage decrying the use of the word ‘probe’ in favour of ‘explore’, which is the point at which I had to go and make a cup of tea. The last advice I need to take from this week’s reading is to listen more and talk less. This I will endeavour to practise at work, and I have asked colleagues at EMTAS to let me know how I get on. I am fairly certain I will find it particularly challenging, and I can already hear those of you who know me well chuckling quietly as they are very well aware that I can talk for England and many other countries besides, given the opportunity.

2nd

November 2018

Undaunted

by the lack of feedback on my academic ramblings, I shall persist as I am sure

at least two of you will be properly interested in this week’s topic, which is

the concept of ‘semi-lingualism’.

This

pejorative term has been used to describe an individual whose first language

has not developed fully in that they are not considered to be ‘proficient’

users of that language. When introduced to another language, such an

individual would not be able to reach ‘proficiency’ in that language either,

lacking the linguistic framework yielded by proficiency in the first language

on which to hang the new language. Or so the theory goes. This

being the case, rather than becoming a ‘balanced bilingual’ (more on that

nebulous notion in a future edition) with comparable ‘proficiency’ (ditto) in

both languages, such an individual would never attain proficiency in

either. Scary stuff indeed.

Several

inherent difficulties push their way to the fore here. The first is that

there is no universally accepted definition of ‘proficiency’ in either a first

language or a subsequent one. In the US, there have been attempts to

measure first language proficiency and MacSwan (2005) discusses the use of

various ‘native language’ assessment tools in the US to determine the

proficiency of speakers of Spanish as a first language in particular. For

MacSwan, there are issues with construct validity with these tests. How,

he questions, can such a test assess a child brought up in a monolingual,

Spanish-speaking household as a “non- or limited speaker of Spanish” given that

the child has no attendant learning difficulties and given what we know about

language development 0-5 years? A review of the types of questions asked

in these tests and the test rubric itself demonstrates a strong bias towards

answers given in full sentences. For instance:

|

Item |

Required student response |

Prompt |

[What is the boy doing?] |

El (niño) está leyendo/estudiando. [The boy is reading/studying.] |

Picture of boy looking at book |

In the above example, most people would give the response “Leyendo” or “Estudionado” (“reading/studying”) rather than responding using a full sentence – and they would be rewarded with a score of zero for this. MacSwan suggests that to give an answer to that particular question using one word reveals “detailed covert knowledge of linguistic structure”, which sounds terribly learned. To what MacSwan says I will therefore add my own two penn’orth and call it an example of “linguistic economy” – a new concept I have just invented to describe beautifully succinct language use in which no syllable is superfluous yet the full meaning is evident. Add to these observations the fact that we only learn about the ‘need’ to answer in full sentence in school, where these US tests are used prior to a child being admitted to full-time education, and a picture begins to emerge of Spanish-speaking children in various states in the US being found linguistically wanting and in consequence penalised and denigrated for having poorly developed first language skills before they have even got off the starting blocks. Furthermore, it is widely held that children exhibit from an early age complex knowledge of such language-related things as word order, word structure, pronunciation and appropriate use of language in particular situations, whatever their first language may be. Most children achieve this by the age of five, in fact, bar perhaps just the latter stipulation which brings to mind those priceless examples drawn from one’s observations of one’s own child’s completely inappropriate use of language in various public fora. Do please send in your own examples of these as mine, which took place at Marwell Zoo just outside the zebra enclosure, is unrepeatable in this context. Back to the matter in hand and for MacSwan, then, it is not the child’s first language proficiency that is being measured with the test question above; it is the child’s ability to suspend his pragmatic linguistic knowledge in favour of compliance with an arbitrary requirement to couch an answer in a complete sentence - in itself an unrealistic requirement, given the child has yet to start school. Hence definitions of ‘language proficiency’ and the ways in which this might be measured are open to debate and, in consequence, so too is the concept of ‘semi-lingualism’ for which I for one am thankful.

Keep tabs on Sarah's journey using the tags below.

Comments

In their last blog article published in the summer term, the Hampshire EMTAS team concluded the academic year with a celebration of their schools’ successful completion of the EAL Excellence Award. Now feeling refreshed after the summer break, the team look forward to the year ahead.

EAL Excellence Award

Our work supporting schools to develop and embed best practice for their EAL learners through the EAL Excellence Award continues. Surgeries will be held to help colleagues get ready for Bronze level and many of this year’s network meetings will focus on aspects of the award which practitioners need to develop for the next level up. For example, many schools will want to work on planning for the use of first language as a tool for learning this year (more on this in a future blog). See the EMTAS website for more information about the Award and how you can introduce it in your school or setting.

GRT Excellence Award

Following the success of the EAL Excellence Award, we have developed a similar award to support schools who have Gypsy, Roma and/or Traveller pupils on roll. At present, we have eight schools piloting the GRT Excellence Award and working towards getting their accreditation. To find out more, please contact: claire.barker@hants.gov.uk

NALDIC Berkshire & Hampshire Regional Interest Group (RIG)

NALDIC is the National Association for Language Development in the Curriculum and has an EAL remit. Part of the work of NALDIC is to run Regional Interest Groups (RIGs) across the country. Many of you may have heard that Dr Naomi Flynn is giving up her role as convenor of the Berkshire and Hampshire RIG. Whilst we are sad as this means we will see less of Naomi, we are also excited that the responsibility will now be shared between Portsmouth EMAS, Dr Anna Tsakalaki at the University of Reading and ourselves at Hampshire EMTAS! We wish Naomi all the best in her new role of Events Chair for NALDIC and look forward to working with our new co-convenors.

Network meetings

EMTAS network meetings are a great opportunity to meet colleagues with an interest in EAL practice and provision, to share ideas and to access input and take part in discussions on a range of EAL-related issues. These termly meetings are free to Hampshire maintained schools; staff from academies or the independent sector are also welcome to attend for a small charge. To find dates and information about how to register for a network meeting near you, see the Training section of the EMTAS website.

EAL E-learning

Our EAL E-learning has been given a complete overhaul this year to bring it up to date. The modules will now play even better in the Chrome browser and are optimised for seamless delivery over mobile devices. Check out our latest module on the ‘Role of the EAL coordinator’ and look out for new modules being developed this year.

SEAL (Supporting English as an Additional Language)

Due to popular demand, this course is running again starting in October 2019. It is a training programme for support staff and EAL co-ordinators to help them build up their knowledge of EAL good practice and pedagogy and has a strong focus on practical strategies to support pupils with EAL within their school environment. The course covers best practice in the classroom, SEND or EAL?, assessment, working with parents of children with EAL and the latest digital technology and resources to support learning in the classroom. If you are interested in signing up for this course, please check details on our website.

NALDIC Conference

This year the NALDIC conference takes place at King’s College London on 16th November (easy walking access from Waterloo station). The conference title this year is ‘Inclusive practices in multilingual classrooms: assessing and supporting EAL and SEND learners in the mainstream’. The NALDIC conference always has a good variety of workshops to suit all tastes, stands from publishers/resource providers and is a great place to network with colleagues from all over the country.

As you can see there are plenty of opportunities to get involved with EAL this year. We look forward to seeing you at an event near you.

Comments

Last September we kicked off our second year of blogging with an article introducing our new EAL Excellence Award, a self-evaluation tool for schools created with a view to support practitioners in developing EAL practice and provision. As they are about to break for their Summer holiday the Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisors reflect on their work with schools using the EAL Excellence Award in their area.

Getting ready

The award was met with much enthusiasm after its

launch in our blog and during network meetings. Practitioners found it helpful

as a way of mapping out the areas where provision was already strong whilst

identifying areas for development. For example, many schools identified the

need to appoint and train an EAL Governor. They reflected on policies and the

importance of writing a stand-alone EAL policy. The self-evaluation tool also

highlighted staff training needs which we supported through bespoke sessions as

well as our e-learning. Feedback from schools indicated that they found

the self-evaluation criteria relevant and purposeful.

Some

schools have collated evidence into folders to make the validation visit as

smooth as possible. They have used each statement from the EXA as a divider and

then placed any appropriate evidence, such as lesson plans, copies of school

policies or photos of work, into each section. This

made the validation process relatively straightforward since all the evidence

could be found in one place. For one school, the portfolio of evidence was

a piece of work which particularly impressed the Ofsted inspectors.

The validation process

Validation visits were, in most cases, carried

out by a Specialist Teacher Advisor not previously connected with the

school in order to get a fresh take on practice and provision. It has also been great

being able to meet Young Interpreters in some schools and in one school there

was even the chance to meet with the school governor responsible for EAL. This was supplemented by tours to see displays and collections of

resources in the library or in classrooms. One tip for schools thinking

about gaining their own award might be to take pictures of anything ephemeral

like a classroom display and keep them in readiness.

What’s next?

Since the launch of these materials in September there

has been interest from colleagues beyond the bounds of Hampshire. Schools have

already purchased licenses to use the tool within their establishment and EAL

specialists have been trained as validators to work with schools in their

own locality. If you are interested in finding out more, please contact: Chris.Pim@hants.gov.uk.

More materials will be produced to support schools

with gaining their EAL Excellence Award in 2019-20. There will also be training

opportunities to support aspects of the framework which some schools have found

trickier e.g. using first language as a tool for learning. We will also work with our current bronze schools who might be thinking

about developing their practice and provision towards silver.

Building on the success of the EAL Excellence Award,

the EMTAS Traveller Team have introduced a Traveller Excellence

Award that is currently being piloted in eight schools all around

Hampshire. We hope to present our first award early in the Autumn

term. This award helps schools audit their provision for their Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities and helps to ensure that all

staff are well informed about the different GRT cultures in their

setting. If you are interested in finding out more, please contact: Claire.Barker@hants.gov.uk.

Finally...

We congratulate the following schools for their hard

work in achieving their award:

Bronze

Cherbourg Primary School, Eastleigh

Cove School, Farnborough

Hiltingbury Infants, Eastleigh

Marlborough Infant School, Aldershot

Merton Infant School, Basingstoke

New Milton Infant School, New Milton

South Farnborough Infant School, Farnborough

St John the Baptist Primary School, Andover

The Wavell School, Farnborough

Weeke Primary, Winchester

Silver

Cherrywood Community Primary School, Farnborough

Harestock Primary, Winchester

Ranvilles Infant School, Fareham

St John the Baptist Primary School, Fareham

Wellington Community Primary School, Aldershot

Visit our website to find out more about the

EAL Excellence Award and contact the Specialist Teacher Advisor for

your area to book a visit:

Basingstoke & Deane: Astrid Dinneen, astrid.dinneen@hants.gov.uk

Eastleigh

and Test Valley: Jamie Earnshaw, jamie.earnshaw@hants.gov.uk

Fareham and Gosport: Chris Pim, chris.pim@hants.gov.uk

Hart, Rushmoor and East Hants: Claire Barker, Claire.Barker@hants.gov.uk

Havant and Waterlooville: Chris Pim, chris.pim@hants.gov.uk

Isle of Wight: Lynne Chinnery Lynne.Chinnery@hants.gov.uk

New Forest – Lisa Kalim, lisa.kalim@hants.gov.uk

Winchester: Sarah Coles, sarah.c.coles@hants.gov.uk

Comments

By Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Jamie Earnshaw

The early morning birdsong, lighter evenings and even maybe some sunshine peeping out from behind the clouds…this can only mean one thing: exam season is upon us.

This academic year, EMTAS Bilingual Assistants have supported over 50 EAL students in schools across Hampshire, and the Isle of Wight, to help them to prepare for their Heritage Language GCSEs. We have supported students who speak Arabic, Cantonese, Polish, Portuguese, Russian and Turkish, to name just a few. I’m sure that both staff and students will sigh a breath of relief to get to the end of the exam season this year!

Whilst we all know how stressful the exam season can be, upon receiving their results, many EAL students are given such a boost of confidence. It may well be an EAL student’s first experience of exams in this country and what better way than to acclimatise to the anomalous experience of sitting in an exam room than doing so in a subject they know well.

Nevertheless, just because a EAL student has grown up in an environment in which their first language has always been spoken, or they have had formal education in their home country, it is so important that we do not take for granted that students necessarily have the skillset to be able to take a GCSE exam in a Heritage Language without support. Do students have the skills across all aspects of the exam, speaking, listening, reading and writing, in order to be able to access the exam with confidence?

Having been brought up in the UK, where I spoke exclusively English, it was not just enough for me to turn up to the exam hall and proclaim my readiness for the English Language exam. In fact, I had 4 lessons each week, during my GCSE schooling years, in which I developed, improved and focused my language skills across speaking, listening, reading and writing. There was also the need to learn how to tackle the exams. How am I expected to answer the questions? Which skills do I need to display? What am I being assessed for?

It is essential for EAL students to have the same opportunity to have those niggling questions answered and to receive appropriate support when completing a Heritage Language GCSE. Attempting and receiving feedback on past papers and rehearsal opportunities for the speaking test are vital. It is also worth remembering that the papers are designed for non-native speakers, so the tasks are set in English. Therefore, for a newly arrived student with very little English, time might be needed to develop skills in English to a level in which they are able to access the questions or, at the very least, get used to the target question vocabulary used in the papers.

Once these initial hurdles have been crossed, the benefits for students really are immeasurable. Often, pupils achieve very good grades in their Heritage Language GCSEs and this can be a bonus when they are applying for college places or apprenticeships. It also gives students that experience of completing a GCSE examination, which, if they do earlier than Year 11, will help to ease any worries about what the experience of sitting an exam is actually like when it comes to perhaps those more daunting subjects like English, Maths and Science.

Visit the GCSE page on our website for more information about the EMTAS GCSE packages of support available to help prepare pupils for Heritage Language GCSEs. When you have decided which package you want, ask your Exams Officer to complete the GCSE Support Request and GCSE Agreement forms and return them both to Rekha Gupta using the address details provided on the GCSE Support Request form (by 1st March 2020).

Good luck to all those students (and staff) anticipating GCSE results this summer!

Comments

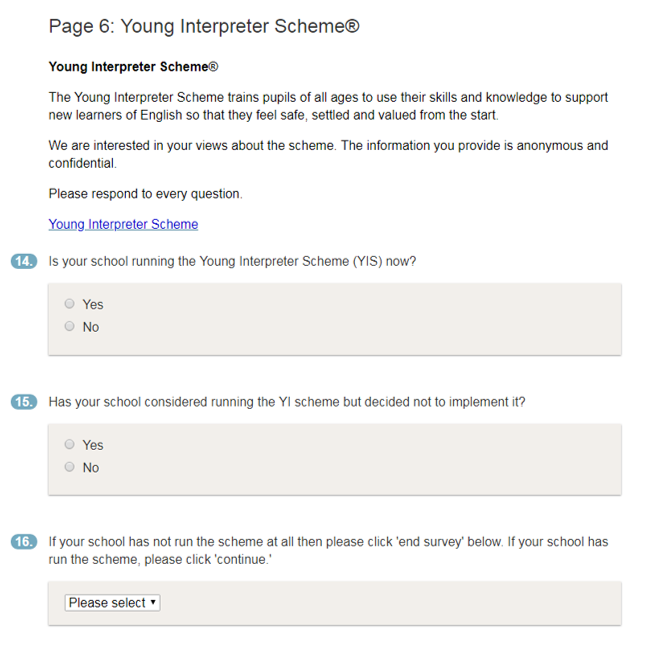

By Debra Page, Masters candidate at the University of Reading

Hi readers. If you’ve not read about me in the Young Interpreters Newsletter, my name is Debra Page. I am conducting research on the Young Interpreter Scheme under the supervision of the Centre for Literacy and Multilingualism at the University of Reading and with Hampshire EMTAS as a collaborative partner. This is the first time the successful scheme will be systematically evaluated since it began 10 years ago. I have worked in research and as an English as a Additional language teacher since graduating with my psychology degree. Now, I am completing my Masters in Language Sciences before starting the PhD. My Masters research dissertation is looking at staff experiences of the Young Interpreter Scheme with a specific focus on motivation for participation in the scheme, views around teaching pupils with EAL and effects of running the scheme on children, staff and schools.

After months of behind the scenes work from the team, a questionnaire has now gone live! The team and I encourage as many staff as possible to complete the questionnaire. This includes people who are running the scheme, who aren’t running the scheme, and staff who work with children with EAL. This anonymous online questionnaire should take around 15 minutes to complete and will allow myself and Hampshire EMTAS to discover what you really think about the scheme, your experiences of participation, and working with children with EAL. Finding out your views in running the scheme (or not) will help EMTAS improve and expand it, plus you will be helping to shape its future.

If you haven’t met me yet, I will be at the Basingstoke Young Interpreters conference on 28th June. If you have any questions about the questionnaire, please email me – debra.page@student.reading.ac.uk.

I hope you choose to help by completing the questionnaire. Please spread the word and share the link!

Comments

At a recent EMTAS teachers’ meeting we had an interesting conversation about how often we find ourselves repeating the same messages to practitioners about what good practice looks like for schools working with new arrival learners of EAL. We wondered what methods beyond face to face training and written guidance might be effective at communicating those core principles.

Of course we already have various ways of communicating good practice principles to schools in our local authority and the wider educational community, including via School Electronic Communications, Young Interpreter newsletters, our Twitter account @HampshireEMTAS, online EAL training materials and even posting on national outlets such as the EAL-Bilingual Google group.

In thinking about new ways to communicate our messages, we were inspired by Rochdale Local Authority’s brilliant video ‘Our Story’, which explores the feelings of new arrivals on their first few days at their new school. We decided to produce our own video that focused on how to settle, induct, assess and teach new arrivals to ensure they have the best possible start in the UK education system.

To produce our video, we decided on a software tool called Videoscribe (from Sparkol). For those of you unfamiliar with this technology, Videoscribe produces those videos where a hand draws images on a white canvas to the accompaniment of a narration and possibly a musical score.

The first task was to write a script to cover the key messages:

baseline assessment, with the avoidance of standardised testing

valuing linguistic and cultural diversity

building upon the skills and aptitudes of each child

effective buddying

mainstreaming teaching and learning

Having written a script, we pooled our ideas around choosing a strong metaphor through which we could visualise the main ideas (sports day theme) and any potential images that would need to be drawn. Working with a local artist we then incorporated those drawings with the narration into the Videoscribe software. The resulting video can be viewed below:

Do signpost this to colleagues, and let us know what you think.

Comments

Mum, I don’t want to go to school today!

By Hampshire EMTAS Bilingual Assistant Eva Molea

This is the 5th chapter of my Diary of an EAL mum, a series of blogs in which I share the ups and downs of my experience of bringing up my daughter Alice in the UK. So far I have spoken about my experience as an EAL child, how we prepared a cosy nest for Alice to feel at home in her new country, how I tried to support her learning, and the sometimes peculiar choices for lunch. This chapter is about attendance.

Author's own image

Unless I was feeling seriously unwell, for me as a child not going to school was NOT an option. Probably because my parents always told me that going to school was my job and that I had to do it as professionally as possible, which meant being neat and tidy - especially at secondary level, where maintained schools in Italy have no uniforms - and well prepared for my lessons. But mainly because staying at home was DEAD BORING. Not going to school meant being locked up at home, no escape. So why would I ever swap a good 5 hours with my friends for the same amount of time on my own?? Therefore, my approach to the subject had always been simple: we all have to go to school. Until... one morning Alice started crying desperately because she didn't want to go to school and that SHE WANTED TO GO BACK TO ITALY RIGHT THEN.

Oh dear me! She was in such a state that, for the first time, I had to consider not sending her to school. I was very surprised though, as Alice had started going to school everyday at the age of 2 (drop off at 9 am and pick up at 2 pm) and had never told me that she didn't want to go to school. What was I supposed to do? I was worried that, had I allowed her to stay at home that day, she would have asked for it again and again. On the other side, to be fair to the child, we had been in the UK for less than a month and she was still finding going to school very hard and tiring because of the massive effort of processing everything in two languages and because of the linguistic isolation she was still experiencing, which she hated.

So I decided to give her a break and spend the whole day together as a reward for her hard work and intense effort. But I made an agreement with her: this would be the ONE AND ONLY exception in her school life (a bit drastic, I admit, but that's it). In Italy I would have just kept her at home, but here I had to call the school by 9 am to tell them that Alice would not be in school that day and why (schools require all parents to do so, otherwise they call you). I tried and tried but to no avail so I sent an e-mail to the School Office and within minutes I received a reply that it was OK to have Alice at home for that day as homesickness could be a real physical and mental condition. I was very grateful for their understanding. Her school is amazing.

Oh no! I had the hairdresser booked on that day, and a class at the gym I really wanted to go to. AARGH! The wise person that sometimes lives within me told me that instead I needed a plan to make the most of our day together so... We started with the hairdresser (I was not giving this up), next out for lunch, then to the bookshop, played some games at home and cooked a nice dinner for dad who, oblivious of all the things we had done that day, had been only at work (note to self: get a credit card on his bank account).

At the end of Year 1 Alice missed the last day of school too. Our tickets to fly back to Italy for the Summer holidays were a lot cheaper if we flew on the Friday instead of the Saturday, so I went to the School Office and they told me that they understood the issue but the absence was not authorised. I must have had a question mark on my lovely face as the Office, without prompting, explained to me that the Head Teacher had to authorise every absence and holidays were not a good reason to be off school. Obviously I could take my child with me but that would appear as an unauthorised absence on the register. I was very surprised to hear that if Alice made too many unauthorised absences we would have to pay a fine. And being late for school sometimes can count as an unauthorised absence. Aaarghhh! Given my Mediterranean concept of time, I would need to set my watch 10 minutes early to make sure we would be on time!!! The positive news was that Alice would be authorised to be absent during term time for weddings and funerals. So hopefully we will have loads of them. Let’s rephrase this: loads of weddings. Friendly advice: if you wish to know more about attendance policies, please ask the Office at your children’s school or visit the Hampshire EMTAS website.

We navigated swiftly through the rest of Year 1, 2 and 3 with Alice being true to her word up to Year 4 when, all of a sudden after the Christmas break, she started saying that she did not want to go to school. Obviously, I stuck to my principle that she had to go to school every day, until she started to get ill. At the beginning, she was complaining of a constant tummy ache and initially I thought it might have been a bug she had caught in Italy over Christmas. But that went on for a long time and we explored all the possible health conditions, but nothing came out. So, my husband and I started to worry about other issues at school we might not be aware of. So, just to test the waters, I offered her to change school and, much to my surprise, she accepted straight away. She then had to give me reasons for leaving the school she had always been so fond of. And here she opened Pandora's box: friendship issues of two different types, unkind friends and much-too-sticky friends; feeling limited in the choice of children she could play with; feeling the competition on academic grounds; a bit of tiredness because of her busy routines outside school; but the worse thing was the anxiety of not knowing who to talk to for the fear of not being taken seriously. As soon as she had told me all that, she felt immediately relieved, such a big weight having been lifted off her chest. As soon as she told me that, I felt like the worst mother ever. Why hadn't she trusted me enough? Was I being too superficial? Was I too busy to give her the attention she needed? Could have I spotted the sign of her uneasiness by myself? All this called for a large bottle of whisky to drain my sadness into (straight translation of the Italian saying “affogare I dispiaceri nell’alcool”). Sadly, I don't drink...

I addressed the issue with the school the following morning and, at pick up time, Alice and I had a meeting with the teachers who had promptly and delicately discussed this in class with all the children and everything was back to normal. I think I might be repeating myself but her school is amazing.

If I had a lesson to take home from my experience this was to pay attention to everything Alice tells me (which is hard work as she is a chatterbox, I wonder who she takes after...). It is in the little things that we can spot any difficulties our children are facing and an early detection can help us set things right before they become worrying.

Anyway, since then, I have never heard her saying "Mum, I don't want to go to school today". But, they say, never say never…

Comments

Sarah Coles shares the second instalment of a journal-style account of her reading for the literature review and methodology chapters of her PhD thesis.

Week 3, Autumn 2018

Week three of the PhD experience and this time I dwell on second language acquisition in early childhood and whether or not there is a difference in one’s eventual proficiency in a language due to acquiring it simultaneously or successively in early childhood. Simultaneous bilingualism is where 2 (or more) languages are learned from birth, ie in a home situation where both languages are more or less equal in terms of input and exposure, a child would develop 2 first languages. I am not volunteering to try and explain this to the DfE, who seem thus far only able to comprehend home situations in which children are exposed to just the one language, but maybe some followers of this blog don’t find it such a strange notion. If so, then perhaps they are in the company of researchers who suggest children growing up in this sort of situation proceed through the same developmental phases as would a monolingual child, and they are able to attain native competence in each of their languages. I personally think there are many variables at play in any teaching and learning situation, things like motivation, confidence, opportunity, resilience and the like, and they all play a part in our lifelong learning journeys. I also think the concept of “native competence” is problematic. What do we mean by that term? How are we measuring it? Do we mean just listening and speaking or reading and writing as well? What about the different registers – does – or should - fluency in the language of the streets count for as much as academic English delivered with Received Pronunciation? Who says so? Then I consider the many monolingual speakers of English I have known; they are not all comparable in their competence in English, despite experiencing a similar sort of education as me, many of them over a similar period of time. Thus ‘native competence’ is not a fixed, immutable thing – in an ideal world, you don’t stop developing your first language skills when you meet the ARE for English at the end of Year 5, do you? ‘No’, I hear you chorus, clearly agreeing with me that it’s a moveable feast. So now even the yardstick implied by the term “native competence” is starting to look a bit flimsy and unfit for purpose. Funnily enough, it wasn’t nearly so problematic until I started all this reading.

Moving swiftly on: if, however, two or more languages are acquired successively, a very different picture emerges from the literature. It has been argued that in successive bilingualism, learners exhibit a much larger range of variation over time with respect to the rate of acquisition as well as in terms of the level of grammatical competence which they ultimately attain. In fact it is doubtful, asserts a guy called Meisel writing in 2009, that second language learners are at all capable of reaching native competence and he says the overwhelming majority of successive bilingual learners certainly does not. Controversial or what? And Meisel is not on his own here; there are many people who agree with the “critical period hypothesis” which essentially boils down to the idea that there is an optimal starting age for learning languages beyond which, and no matter how hard you try, you will never become fully proficient (whatever that means). Johnson and Newport (amongst others) say this age is between 4 and 6 years - which makes me feel a bit downhearted, like I have completely missed the bilingual boat here. Curses.

It all makes for a rather depressing prognosis for older EAL learners, those late arrivals for instance, yet we know from other research that those of our EAL learners who’ve had long enough in school in the UK can achieve outcomes at GCSE that are comparable with their English-only peers, and this can only be a Good Thing, opening doors for them as they go through their teens and into adulthood. For next time, I will try to read something more uplifting, though I expect whatever that turns out to be it will raise more questions than it answers. Keep tabs on the journey as it unfolds using the tags below.

Comments

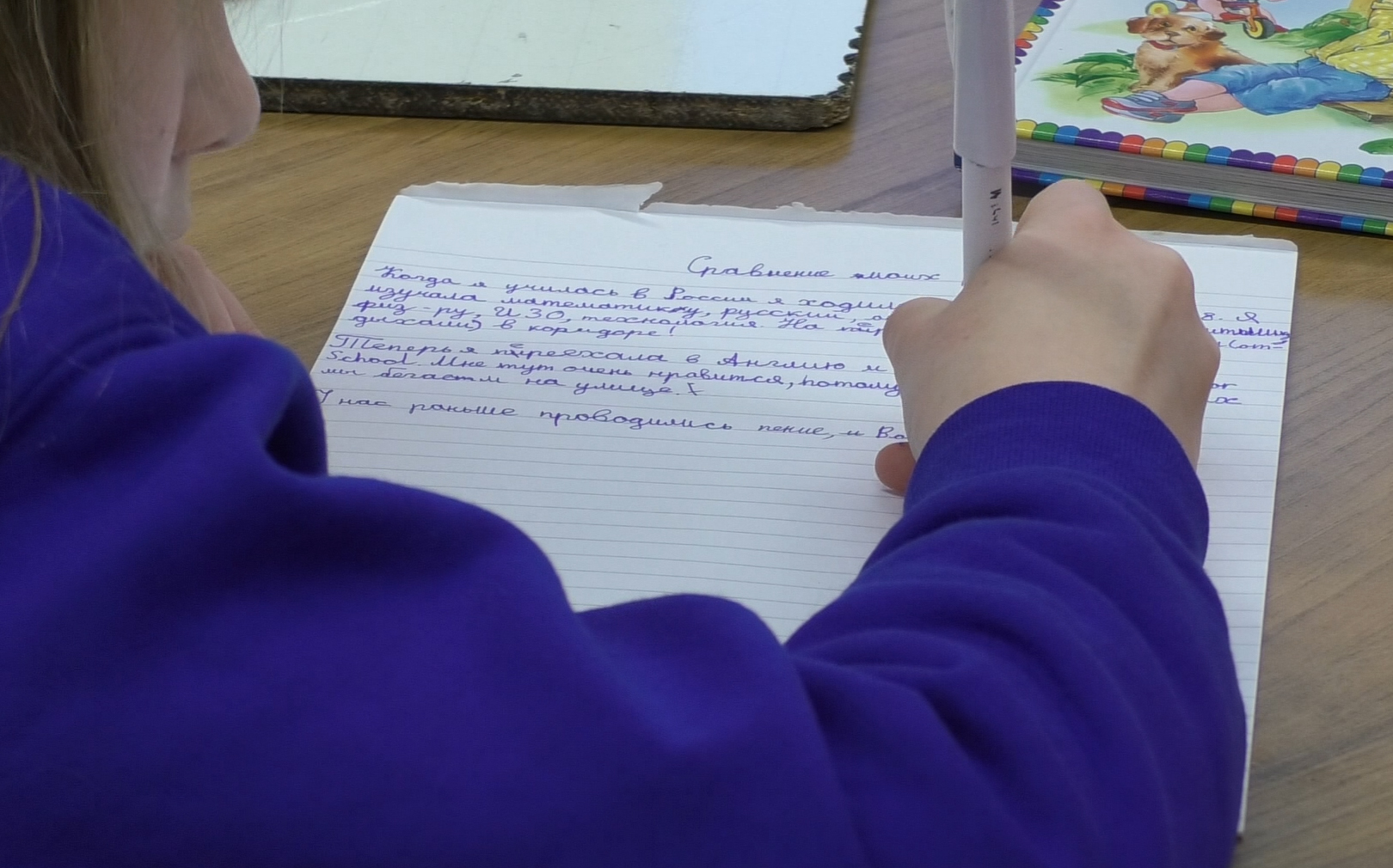

By Hampshire EMTAS Bilingual Assistant Luba Ashton

It can be very challenging for many school practitioners to start working with new EAL arrivals who have either very limited or no English language skills. In this situation, the school staff may have a lot questions and many of them can be about the pupil’s native, or first language skills:

Is the child speaking at an age appropriate level?

How proficient is this pupil in reading and writing?

Is the pupil working above or below age related expectations?

It is very important to find the answers to these basic questions sooner rather than later to start developing the pupil’s English skills with support of their first language prior knowledge and skills.

The best solution is always to invite an EMTAS bilingual assistant to carry out an assessment and get important insight in pupil's educational and cultural background. But when EMTAS are not immediately available, is there anything the school practitioners can do in the meantime, even when they do not share the pupil’s language?

It may sound surprising - but the answer is yes.

This is made possible with the help of the First Language Assessment E Learning resource, created by EMTAS. Using this E Learning tool, practitioners are given advice about how to carry out an assessment of pupil’s skills even in an unfamiliar language.

This resource will explain how to make judgement about reading proficiency; clarify comprehension, notice various features such as accent, intonation, expressing punctuation. It will also help to identify specific strengths and weaknesses in writing; handwriting, quantity, punctuation, self-correction etc.

The E Learning resource provides a practical step by step guide. It is structured into a few parts and gives very detailed instructions on how to assess listening, speaking skills and also reading and writing skills for pupils who are literate in their first language.

Other important steps explained are:

how to prepare for the first language assessment

how to guide and encourage the pupil

best practice to conduct the assessment

how to interpret the outcome of the assessment

how to use the results to further support the development of the pupil’s English skills.

The E Learning resource uses a real life case study of a new arrival Year 6 pupil, Maria. She is a native Russian speaker. The videos provide very useful guidance and enjoyable viewing. It is amazing how much you will be able to say about Maria’s Russian skills without being able to speak Russian!

The materials also provide users with a variety of interactive tools, a check list and links to other resources to support the assessment together with explanations of how to use and where to find them. It is set out to enable the practitioner to make an informed decision as to whether the pupil works at an age appropriate level and help highlight any potential issues.

Feedback from practitioners using this resource has been very positive and I am sure it will be a valuable support for the early assessment of EAL pupils. Visit Moodle for more information.