Blog entry by Astrid Dinneen

Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Lisa Kalim separates fact from fiction

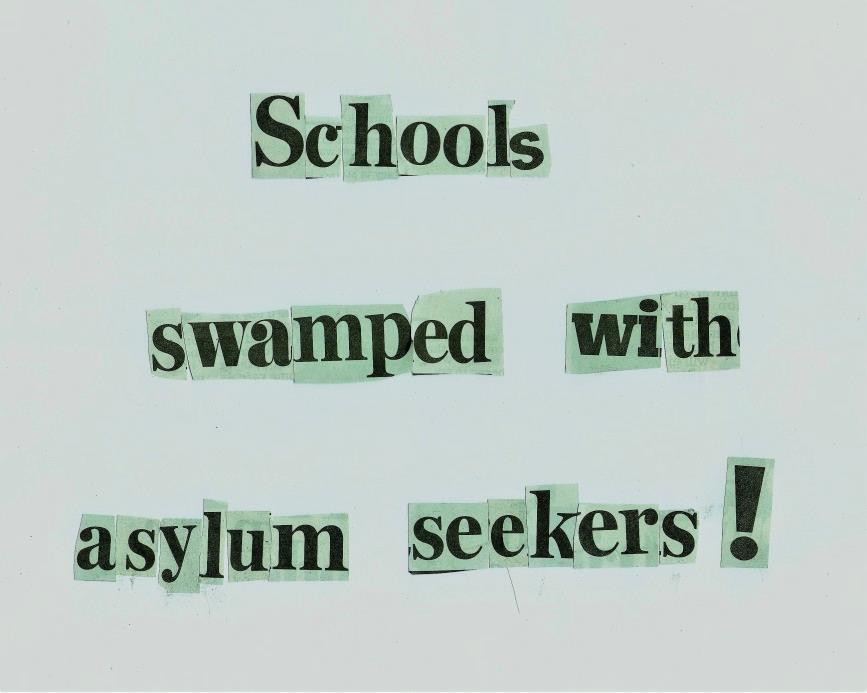

If you read and believe certain tabloid newspapers you may well have reached the conclusion that UK schools are struggling with a large influx of asylum-seeking children and young people. However, this view is not supported by the most recent data released by the Home Office in February 20181. These give the details of all asylum applications made by children in 2017 and compare the data with the previous four years. Applications from Unaccompanied Asylum Seeking Children (UASC) and those that arrived in the UK with an asylum seeking relative/guardian are included in the data so all children who were seeking asylum during this period have been considered.

How many asylum seeking children started at British schools in 2017?

Probably far fewer than you think. In 2017 a total of 2,206 children applied for asylum in their own right, down 33% from the previous year. Of these, 71% were aged 16-17, 22% were aged 14-15 and 4% were aged under 14 with a further 3% of unknown age. All are entitled to a school or college place. An additional 2,774 applied as dependents of adult asylum seekers, making a total of 4,980 children. Some of the latter were under the age of 5 years at the time of their relative/guardian’s application and so would not all need a school place straight away. When you consider that there were 8,669,085 pupils in UK schools in 2017 (DfE, 2017)2 but only 4,980 of these were newly arrived asylum seekers, it would seem clear that schools are not being swamped by asylum seekers. How can they be when one year’s worth of newly arrived asylum seeking children make up less than 0.05% of the total school population?

But don’t some areas get more than their fair share of asylum seeking pupils?

The UK operates a policy of dispersal for asylum seekers to avoid particular areas receiving much larger numbers than others. This has been in place since 2000 for adult asylum seekers and their families and whilst it is not a perfect system (it has had criticism for removing new arrivals from their extended family in the UK, for example) it has meant that any particular area should not receive more than one asylum seeker per 200 of the settled population and therefore no area should feel ‘swamped’.

For UASC, a new scheme called the National Transfer Scheme has been in place since 2016. Similarly, it limits the numbers of UASC for whom any particular Local Authority is responsible to 0.07% of its total child population. Again, this should mean that no single area should receive a larger number than it is able to manage.

Didn’t the UK take in lots of children when the Calais Jungle closed?

Between 1st October 2016 and 15th July 2017 only 769 children were permitted to move to the UK from the camps in Calais. There were 227 children from Afghanistan, 211 from Sudan, 208 from Eritrea and 89 from Ethiopia. The rest came from a variety of countries, with fewer than 10 children from each. Nowhere near enough to swamp UK schools.

Where have the rest of the children come from?

Sudan is now the country of origin for the largest number of UASC. 89% of all applications in 2017 were from the following 9 countries: Sudan (337), Eritrea (320), Vietnam (268), Albania (250), Iraq (248), Iran (213), Afghanistan (210), Ethiopia (74) and Syria (41). 89% of these children were male. For female UASC Vietnam is the most common country of origin.

For children arriving with a relative or guardian, the countries of origin are similar but with the addition of Pakistan, Bangladesh and India. Numbers from Sudan and Vietnam have increased significantly since 2016, whereas numbers from Iran and Afghanistan have decreased. In contrast to UASC, around 66% of children that arrived with a relative or guardian are female.

How many children are granted refugee status and allowed to stay in the UK?

1,998 initial decisions relating to UASC were made in 2017. Of these 1,154 (58%) were granted refugee status or another form of protection, and an additional 378 (19%) were granted of temporary leave (UASC leave). A further 23% of UASC applicants were refused. This will include those from countries where it is safe to return children to their families, as well as applicants who were determined to be over 18 following an age assessment.

For children with a parent or guardian their decisions are linked to their adult applicant’s. So, if their parent or guardian is granted refugee status, the children are too. In 2017, 68% of asylum applications (excluding UASC) were refused. Only 28% were successful and an additional 4% were granted other types of leave. The numbers being granted refugee status are the lowest that they have been in the last 5 years. The numbers of refusals increased in 2017 compared to previous years. Pakistan, Bangladesh, India and Nigeria have well above average refusal rates, whereas children from Iran, Eritrea, Sudan and Syria are most likely to be granted refugee status. Those refused can choose to appeal the decision. In 2017 only 35% of appeals were allowed, while 60% were dismissed. This means that a large proportion of the asylum seeking children arriving in our schools will not be permitted to remain in the long term.

So, are our schools being swamped with asylum seekers or not?

Based on the facts, I would say definitely not but you make up your own mind. Some schools may have more asylum seekers than others but this does not mean that they are swamped. The numbers arriving overall are falling.

References

1 Refugee Council (February 2018) Quarterly asylum statistics [online]

https://www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/assets/0004/2697/Asylum_Statistics_Feb_2018.pdf

2 Department for Education (June 2017) Schools, pupils and their characteristics: January 2017 [online] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/650547/SFR28_2017_Main_Text.pdf