Site blog

By Hampshire EMTAS Team Leader Sarah Coles

This blog is about terminology and our understanding of a specific group of children for whom English is an Additional Language: heritage language speakers.

Most practitioners who’ve spent any time at all working with

multilingual learners in schools will be familiar with the concept of the

international new arrival; children who come to the UK from overseas having

been immersed in another language from birth.

Where they are typically developing, these children’s first language

skills will be broadly similar to those of anyone who’s had a monolingual start

in life. Older learners who have been

schooled in their language (L1) in country of origin may have literacy skills

as well as oracy, whilst younger children who’ve not yet started to learn to

read and write may have age-appropriate oracy skills only. Whatever their skills in L1, it is often

shortly after their arrival to the UK that these children embark on the task of

adding English to their repertoire, hence they might be described as ‘sequential

bilinguals’; L1 first, followed by English.

Heritage language speakers are a bit different. The term ‘heritage language speaker’ is used to describe a child growing up in a society where their home language is not the same as the majority language. For example, a heritage language speaker might be a child born in the UK to Polish speaking parents. The main language in use at home might be Polish but outside of the home, they will also have exposure to English, the societally dominant language. For these children, the model of bilingualism is ‘simultaneous’; exposure to both languages from birth (or shortly after). What this means is that whilst such a child might have access to good L1 role models at home, overall their access to Polish is typically less than had they been born and raised in Poland. So they may present with different skills in L1 in comparison with a monolingual Polish-only child.

Many UK-born heritage language speakers have their first experience of being immersed for prolonged periods of time in an all-English environment at pre-school. They will, from that point onwards, rapidly develop their vocabulary in English, alongside the continuing development of L1. However, due to their more limited exposure, it would be expected that their L1 oracy skills might develop more slowly than those of a child born and raised in an essentially monolingual setting, where the main language in use in all social situations is L1.

As they reach school age, heritage language speaking children suddenly experience a dramatic increase in the amount of time they spend in social settings where English is dominant. This typically corresponds with a reduction in access to L1. Whilst in Year R, they may find opportunities to continue to use L1, for example in their spontaneous play with other children who share the heritage language; but in adult-led activities they quickly learn that English is required. Often, it is from the start of school that heritage language speakers’ L1 development plateaus whilst their English comes on in leaps and bounds. There can develop a dichotomy in terms of the words the child knows in their two languages too, with the academic vocabulary known only in English and L1 increasingly beached in informal, home-based contexts. Further, parents often notice that when addressed in L1, their child prefers to respond in English.

Thus from Year R onwards, it takes considerable effort on the part of parents to ensure their child does not lose the heritage language. This is where the Family Language Policy (FLP) comes in. FLPs are important in determining whether or not the heritage language will be successfully transmitted to the child and maintained over time, and comprise the unwritten ‘rules’ around language use in the home. In families where parents continue to use L1 at home, its transmission and maintenance tend to be more successful. But in families where parents gradually abandon L1 in favour of English, which is especially likely in families where one of the parents is a monolingual English speaker themselves, the prognosis is much bleaker. Ceding L1 in favour of English might be prompted by their children’s growing preference for the majority language, but the often unintended consequences can include those same children no longer being able to talk to their grandparents, with the chances of the heritage language surviving to the next generation, their children’s children, reduced to zero.

So what does this matter to practitioners? Well, especially in the Early Years, it is

important that schools work closely with parents if the complete loss of the

heritage language is to be avoided. These

days, ICTs gift us with lots of ways in which we can make space for children’s

L1s in Foundation Stage settings, and it’s really important that practitioners

avail themselves of these. If they do

not overtly value children’s L1s and encourage their use at school, children

will quickly learn to leave their heritage languages at the school door to wait

for home time.

To find out more about ICTs that could be used at school to promote children’s heritage languages, see

Use of ICT (hants.gov.uk)

By Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Astrid Dinneen

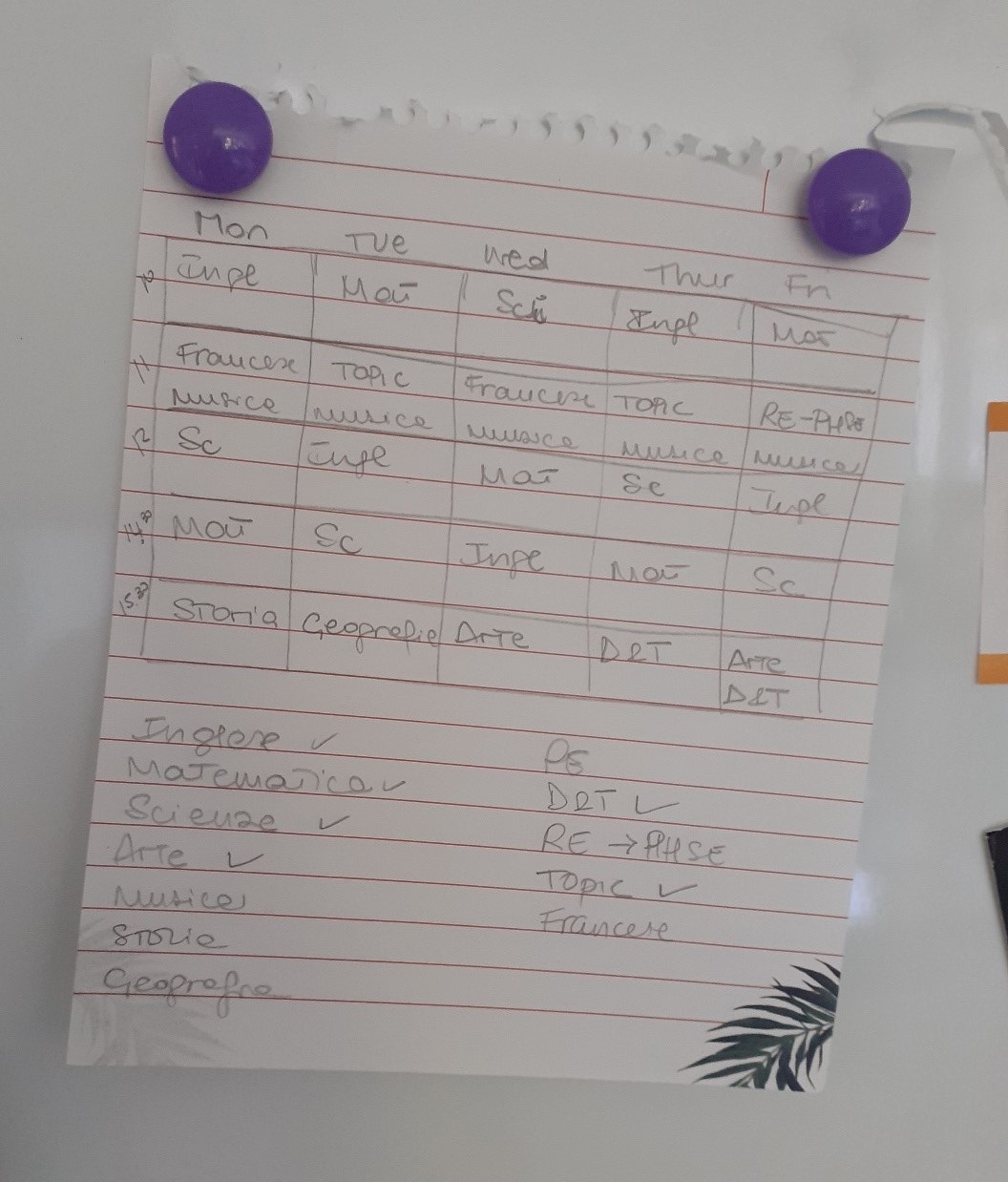

This term we are launching a new and innovative form of support for pupils in Years 5 and 6 and KS3/4 who are literate in their first language.

The EMTAS Study Skills Programme will be delivered to suitable pupils in withdrawal by EMTAS Bilingual Assistants. It aims to help pupils explore how they feel about their learning and their subjects and to equip them with different tools and strategies they can apply in their lessons and home learning. For example, pupils will explore and annotate texts using Microsoft Translator, learn to use Google Lens to create a glossary, have a go at using Immersive Reader to access information and much more.

The programme consists of 5 sessions of 50 minutes. Each session has been meticulously planned and resourced by the EMTAS team to offer a predictable and consistent scheme of work - regardless of the language in which it is being delivered. For instance, pupils will typically start their sessions by sharing how they have used the tools and skills covered in the previous session in class or at home. They will then consider how they feel about learning a new skill at the start of the session and revisit this again at the end. A new tool and strategy will usually be demonstrated by EMTAS staff and pupils will have the opportunity to have a go themselves using their own or school device. This will offer pupils the space to practise their new skill through the context of what they are currently learning in class. At the end of the final session, pupils will be awarded a special notebook for their hard work both during and between sessions.

The Bilingual Assistant team has worked tirelessly over the last few months to upskill themselves in delivering the programme which is now reaching the end of the pilot phase. We are ready for a full rollout after the October break and look forward to working with you to make the programme as meaningful as possible for pupils. We have reviewed our procedures and adapted our communication folder. EMTAS staff will use this document to feed back on what the pupils have focussed on during their sessions, how they have participated and what skill and IT tool they will be applying in class. This written feedback, together with continued open conversations with our staff, will give you a chance to reflect and build these very skills into your own practice, allowing pupils to draw links between the programme and their lessons. To sharpen your own IT skills and keep up to speed with the technology we’ll be using with your pupils, why not join one of our network meetings?

To find out more about the programme, please visit our website and download a flier. Please also sign up for our free network meeting on Monday 6 November at 9.30.

By Hampshire EMTAS Team Leader Sarah Coles and Astrid Dinneen, EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor for schools in Basingstoke & Deane

With the increase in numbers of children joining our schools from overseas with very little English, practitioners in schools are asking how best to proceed. Should they first focus on teaching the children English or is there another approach?

EAL best practice tells us that the best thing to do for such children is to include them in the full mainstream curriculum being delivered in schools via the medium of English. This can be scaffolded in various ways. The children should not be withdrawn to be taught English separately or as a prerequisite to being allowed to join their peers in regular lessons. But this immersion approach can seem an alarming response; surely the children will not be able to understand anything and will flounder and fail, people may think. So instead some opt for an ‘English first’ approach. They buy in an online English teaching app or print off worksheets for the children to learn the days of the week and the colours in English whilst their peers are learning about how plants grow or the story of The Titanic or Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

The problem with the English first approach is that far from helping, it actually slows down the children’s progress in their acquisition of English, as well as making it harder for them to feel welcomed and included in the life of their new school. Plus it adds to teachers’ workloads; now they are having to source materials for an entirely separate curriculum as well as plan for the rest of their class.

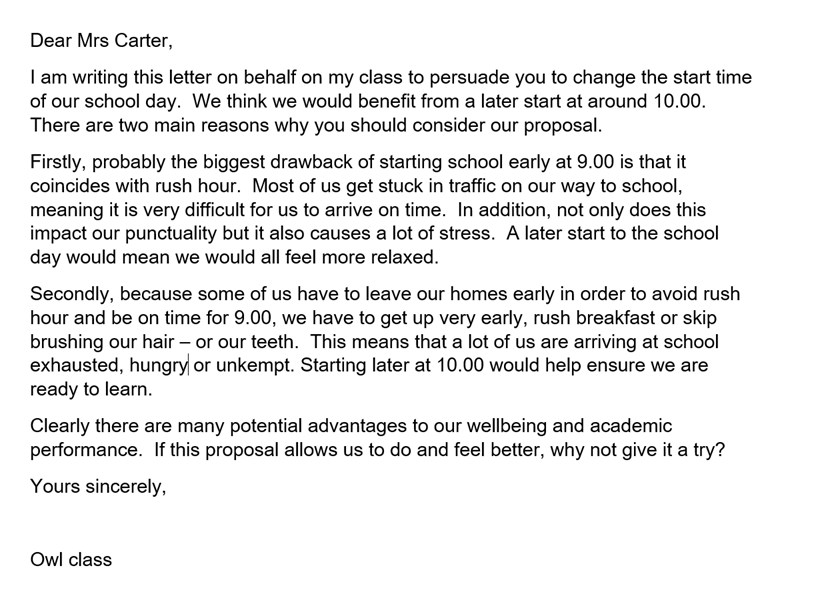

To illustrate this in more detail, consider these two

approaches for the same newly arrived child whom we shall call Hatice*. Assume Hatice

is new to English (Bell Foundation EAL Assessment Framework Band A, to those in

the know) and literate in Turkish.

Scenario 1: English first

The teacher decides to plan separate provision for Hatice, because they feel their mainstream English lesson is too challenging for Hatice’s level of English. So whilst the other children are preparing to write a letter persuading their Head Teacher to shift the start of the school day back by an hour so they start at 10.00 instead of at 9.00, Hatice will sit on her own and work through some sheets that focus on learning the English words for some colours and common classroom objects. In one example below Hatice is required to draw and colour the correct classroom object in the empty box.

It is a…

|

red |

pen.

|

|

purple |

book.

|

|

|

orange |

chair.

|

|

Fortunately, Hatice is compliant, meaning the teacher can get on with teaching the rest of the class. Hatice spends the whole morning working on these worksheets on her own. She doesn’t disrupt anyone but the teacher notices that she regularly has her head down on the desk and appears to be dozing.

At the end of a couple of weeks at school, Hatice is still very much on the periphery of things in the classroom and needs frequent reminding when she is included in instructions given by the teacher, for example when it’s time to get ready for PE or line up to go to assembly. She spends long periods of time gazing out of the window and generally seems to lack motivation and enthusiasm for anything other than home time.

There has also been a deterioration in her output and she

now very rarely completes the worksheets she is given. Where she has had a go with

tasks that require writing, her handwriting is much less tidy and it seems she is

taking increasingly less care over her work.

With regards to friendships, it seems to be still very early days and Hatice has not formed any strong relationships with her peers. She continues to spend most of her time at break and lunch times on her own.

Her teacher reflects on practice and provision so far. It has

taken a lot of time planning, resourcing and marking the worksheets for Hatice,

yet she does not seem to be making progress. He is not sure what else to do but

feels this is not a sustainable approach in the long term. He is interested in

finding out about alternatives…

Scenario 2: immersion using EAL-friendly strategies

Hatice’s teacher plans to include her in the lesson along with everyone else from the get-go. First off, before the series of lessons begins, the teacher sends Hatice home with a list of words in English to be translated into Turkish with the help of parents. He asks them to talk to Hatice about the concept of ‘persuasion’; what does the word itself mean and in what in real life scenarios might we use persuasion to get the outcome we desire? The teacher recommends the family use a translation tool like Google Translate to help them to do this:

English word/phrase |

Turkish (Türkçe) |

Persuade (someone to do something) |

ikna etmek |

We think |

düşünürüz |

Benefit |

|

Consider |

|

Because |

|

Late/later |

|

Traffic |

|

Drawback |

|

Ensure |

|

Potential |

|

The words the teacher chooses for this are drawn from a model letter which will be used in the lesson the following day. The teacher chooses to write the model himself to incorporate the language of persuasion, different persuasive techniques and ideas already suggested by the children themselves. At other times, he might have used ChatGPT to generate a model in no time.

Having diligently completed her pre-learning at home with

the help of her parents and discussed the concept of persuasion in Turkish, Hatice

is very proud to bring in a dual-language glossary she has started in her

special book. She places it on her desk

next to her pencil case. Her new buddies seem to be taking an interest in the

stickers she has stuck on her book and this adds to her feeling of pride.

She is also pleased to recognise the vocabulary she has researched and translated in a handout placed on her desk by her teacher. Everybody else is given the same handout. Hatice is intrigued and delighted to see she might not be doing different work today. Plus a Teaching Assistant approaches her holding a tablet and shows her how to scan the text to translate it into Turkish. Hatice smiles and chuckles as she reads the translation and discovers the text is a letter asking their head teacher to delay the start of the school day.

Highlighters are distributed and her buddies start a conversation. They’re highlighting parts of the letter. Hatice checks the tablet to see the translation again and tries to match the highlighted text to the translation. She starts to neatly annotate her letter in Turkish. Her teacher looks happy so she continues her annotations and adds to her dual-language glossary words such as ‘firstly’, probably’, ‘clearly’ etc. Her buddies highlighted them so Hatice thinks they must be important.

Later on, the children are to write their own letter using

features of the original. Hatice’s teacher suggests to her that she could write

her letter in Turkish. Hatice happily engages with this, writing fluently and

at length, sometimes self-correcting and adding punctuation. She writes in

paragraphs and her sentence starters seem to vary. She even attempts to

incorporate some English vocabulary eg ‘firstly’ and ‘clearly’. This reassures Hatice’s

teacher who can see she has lots of ideas and things to say. He notices Hatice

sometimes looks at her peers’ writing - both are quite happy to show her their

work – and is making use of the tablet to communicate with them using translation

apps.

What now?

Experimenting with EAL pedagogy has proved promising as it’s meant Hatice has felt included, motivated and able to meet curriculum objectives in a differentiated way. Her teacher would like to build on this by trying other EAL strategies such as substitution tables and Dictogloss, planning further opportunities for listening and speaking and continuing the use of Turkish as a tool for learning. To explore these further why not join one of our online network meetings?

EMTAS

training courses | Hampshire County Council (hants.gov.uk)

*This child's name is pronounced /hætidʒe/

In this blog, the Hampshire EMTAS Teacher Team considers what best practice might look like in relation to catering for the needs of refugee children on roll in Hampshire Schools.

In recent months, Hampshire has hosted a number of refugee families from Afghanistan, some of whom will remain in the county permanently whilst others will eventually be found a permanent home elsewhere. The children of these refugee families are starting to be taken onto roll at schools across the county, and this has raised a number of questions as colleagues have sought advice on how best to streamline support at this vital point in the children’s lives.

First and foremost, at the point of referral to EMTAS it has become apparent that not everyone is confident when it comes to telling the difference between an asylum seeker and a refugee. To cut to the chase, the term refugee is widely used to describe displaced people all over the world but legally in the UK a person is a refugee only when the Home Office has accepted their asylum claim. While a person is waiting for a decision on their claim, he or she is called an asylum seeker. Some asylum seekers will later become refugees if their claims for asylum are successful.

The recently-arrived Afghan refugee children are here with their families and because of this they benefit from greater continuity in terms of support from their primary care-givers. Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children (UASC), on the other hand, are minors who are here on their own and therefore don’t have the support of their close families. UASC are accommodated in the care system in the UK but their status in the longer term remains in question. They will be claiming asylum, which – if they are successful – will give them indefinite leave to remain and refugee status. This will give them the right to live permanently in the UK and to pursue higher education and/or work in the UK. Check the EMTAS guidance for more detail on this point.

Moving on to talk about refugees, in many ways the needs of

refugee children are very similar to those of any other international new

arrival, hence staff in schools should, in the main, adopt the same EAL good

practice with these children as they would any others. There are, however, some additional things to

bear in mind.

Refugee children (as well as UASC) may have had to leave their country of origin suddenly, bringing with them very few of their personal belongings and leaving much behind. Because of this, some may experience a greater sense of loss than children whose move to the UK was undertaken in a more planned way. Some refugee children will have left behind members of their extended families as well as friends, favourite toys and pets (where keeping pets is part of their culture), and may be concerned for their safety or not know their whereabouts or even if they are alive. This can be compounded by having little opportunity to communicate with them to check if they’re OK. Older children are likely to be more aware of and affected by this than younger ones, and their awareness may be heightened by conversations within their household as parents talk about and begin to process the events that brought them here.

Some refugee children will have experienced unplanned interruptions to their education, especially those who have spent time in refugee camps en route to the UK or those who have travelled with their families through various countries. Lack of facilities might mean that some have missed opportunities to keep up with their learning, hence there may be gaps. The longer the gap, the more they will have missed – hardly rocket science, but something to bear in mind when thinking about reasons why a child’s reading and writing skills may not be as secure as would normally be expected. The advice with this would be to clarify each child’s education history with parents and then to consider what arrangements might be put in place to help plug any gaps – without causing them to miss even more eg through ill-timed/too many withdrawal interventions (see EMTAS Position Statement on Withdrawal Provision for learners of EAL).

For most refugee children, routine really helps. They benefit from knowing what each school day will hold, so things like visual timetables are helpful. They also benefit from being supported to quickly develop a sense of belonging in their new school. Use buddies – including trained Young Interpreters – to support them as they adjust to their new surroundings. Bear in mind that the less-structured times such as break and lunch times can be more difficult for a newly-arrived refugee child, so check that they are being included and are joining in with play with other children. Teachers may find it helpful to teach some playground games in the relative safety and calm of the classroom, with input and support from other children in their class, with the idea that these games can then transfer to the outside areas.

Support from their peers will be key to the induction and integration of a newly-arrived refugee child. Sit them with peers who can be good learning, behaviour and language role models. Try to match them with peers who are of similar cognitive ability. Remember to reward all children involved with praise where things have gone well eg if they have shown the new arrival their book or repeated an instruction or the new arrival has accepted support from a peer or tried to involve themselves in a task or whatever. With younger learners, consider using a Persona Doll to explore ways of supporting the new arrival with your class.

When it comes to accessing the curriculum, remember the benefits of using first language both to aid access and engagement and to give the child a sense of the value of the L1 skills they bring with them. Use of L1 can be a great way of involving parents too, so make sure you think of ways they can support – perhaps helping their child look up key words or using Wikipedia in other languages to research a topic. If you have a literate child in your class, encourage them to write in L1 and explore how translation tools can be used to build a dialogue with the child and give them the skills to communicate their ideas with others in accessible ways. Many translation tools have an audio component too, so even children who can’t read very well in L1 can benefit from their use in the classroom. For more information about translation tools, see ‘Use of ICT’ on the EMTAS Moodle.

The biggest issues often relate not to language barriers but to culture; there are lots of things we take for granted to be commonly understood, shared experiences which for refugee children will be new, alien. These can include experiences of teaching and learning, for instance a didactic approach wherein the teacher conveys knowledge to the empty vessels that are their charges may have been the norm in country of origin. People whose schooling embodied this sort of approach may find learning through play or learning through engaging in dialogue with others very ‘foreign’; uncomfortably new territory they need to negotiate without any prior experience on which to base their understanding or response.

Refugee children from Afghanistan will almost invariably be Muslim and this in itself raises some issues that schools will need to address. For some children, there will be issues with school uniform, with others, schools may need to rethink key texts they are using in class eg ‘The Three Little Pigs’ with younger learners or ‘Lord of the Flies’ with children in secondary phase may be problematic. For guidance on these and other issues to do with having Muslim children on roll in your school, see the comprehensive guidance from the Muslim Council of Britain (MCB), posted in an open access course on the EMTAS Moodle here.

So to some final advice on how to negotiate this unfamiliar terrain. For one, try to remember always that refugee children’s responses may at first seem strange or oppositional or even rude. This sort of thing is likely to be indicative of a cultural barrier that needs to be overcome with both parties open to moving their respective positions. To get the best results, try to be the party that is receptive to difference and willing to make the most moves to understand and accommodate. If issues arise and you’re not sure what to do, EMTAS is here to support so do get in touch with us.

By phone 03707 794222

By email emtas@hants.gov.uk

Find out more:

By Hampshire EMTAS Bilingual Assistant Eva Molea

In my Diary of EAL Mum I share the ups and downs of my experience of bringing up my daughter Alice in the UK. After 9 weeks of lockdown and with the happy prospect of school re-opening, I reckon it is time for me to reflect on the last couple of months, especially on the irregular shape that Alice's education has taken.

I would like to start with a big shout out to all teachers, TAs, and school staff in general. You, guys, are my true heroes. Where do you get all your patience from? How can you manage with 30 children, day in - day out for 39 weeks a year, when my own one has driven me round the bend in not even 10 weeks??

Anyway, let's get back on track. When the nation was told that the 20th of March would have been the last day of school for the foreseeable future, I was hit by an education frenzy, so I went to the bookshop and bought:

- as many learning packs as I could possibly carry

- two books that I believed Alice should read (=I wanted to read) and one that she had asked for

- a pack of story cubes

- a notebook as we are always short on paper, and a letter set should she ever feel the need for correspondence

- a jigsaw puzzle of the periodic table of elements

- sketchbook (hoping that Alice would keep a diary of this peculiar period).

Proud of my shopping, I showed it to Alice when she came back from school on the 20th of March, but her reaction was far less enthusiastic than I had expected. I wondered why...

The school had provided her with SATs buster test booklets for maths, SPaG and reading and a grid of activities on Ancient Greece. They had also set tasks on the digital platforms for the children to complete.

On Sunday the 22nd of March, I sat down with my husband (aka the Headmaster) and made a learning plan for the first week: 5 days, 5 subjects per day. I was very proud of my broad and balanced curriculum.

So, on Monday morning, bright and early, we sat down to work. We focused on the booklets and the digital activities and easily Week 1 was out of the way.

On Week 2, having completed all the booklets and digital tasks, we approached the Ancient Greeks grid. I really enjoyed this topic. In Southern Italy, also known as Magna Graecia (Big Greece), Ancient Greek culture had shaped ours well before the Romans, and we learnt the ins and outs of it in school, so it was lovely to be able to share this with Alice. We did some learning on the BBC Bitesize website; we read some myths from books we had brought with us from Italy; we used the story cubes to write Alice’s own myth. But I was not satisfied. So, we had a Greek Day, where we:

- tried to learn Sirtaki, the Greek traditional dance, following some videos on YouTube;

- dressed Alice up as a Greek Goddess (YouTube tutorial);

- learnt the alphabet and the polite words in modern Greek, and looked at how Greek language has influenced most European languages, including English;

- cooked pastitsio and tzatziki, following the recipe that my lovely Greek colleague, Eva P, had recommended. And bought baklava…yum!

This was a great way for the whole family to learn new things and share our knowledge with Alice.

Weeks 3 and 4 of lockdown were the Easter holiday, and my lovely child decided she was not going to touch any schoolbooks and the Headmaster agreed, so I could be off task too and enjoy the sunshine. We did a lot of drawing tutorials on the YouTube channel of the children’s illustrator Rob Biddulph, that are glued in the sketchbook.

Alice devoured one of the books I had bought for her (The boy at the back of the classroom), and tried the other one (When Hitler stole pink rabbit) but found it too hard (or not interesting enough, I’m not sure). Fortunately, dance and gym went virtual that week, so we had enough to keep her entertained. We also played some traditional Italian card games.

Getting back to work on week 5 proved to be quite hard. By then, Alice was feeling very lonely and bored because we did not have the skills to keep her interested and, not to be underestimated, we also had some work to do. But fortunately, the school set more structured homework for the children and we were not sailing in the dark anymore. Having daily work to complete was very helpful, as Alice had some tasks she could carry out independently and ask for the occasional help, whereas when she had to make research on the Internet I was a bit concerned about the appropriateness of content she might come across. For guidance, I also re-read the EMTAS information leaflet on safeguarding and wellbeing which includes online safety .

From week 5 onwards, home learning has been an emotional rollercoaster. We have gone from enthusiastic reactions to some tasks to flood of tears for others, covering all the shades in between. Obviously, had Alice been in school, her learning would have been tailored to her abilities (including the right challenges) and more interesting for her. But I have to say that I really enjoyed learning with her, especially because we all had a very intense EAL experience as we used Italian to investigate, question, explain and reinforce everything and both the Headmaster and I have noticed that Alice’s Italian has improved and her vocabulary has widened, with many new and more interesting words being used. She has also enjoyed listening to audiobooks in Italian and asked me to read to her in Italian at bedtime. EAL parents will be interested in this survey on multilingual language use during the COVID-19 Pandemic.

I pushed my luck and asked her how these 9 weeks had been for her. At first, I got a single word answer: “Boring”. I was expecting that. But then she told me that using Italian for maths had made the subject easier as she still counts in Italian (I didn’t know that), that she felt that her translation skills had improved, and her vocabulary in both languages broadened.

Despite the strangeness of this lockdown period, I really enjoyed playing school with Alice and loved seeing her eyes brighten up when there was something that interested her or when she had finally secured the concepts she was struggling with. But now we all, especially her, can’t wait to get back to school.

PS: The lovely learning packs I had bought have never been touched in these 10 weeks. I will have to force them upon Alice during the Summer holidays…

Visit the Hampshire EMTAS website

Visit our Distance Learning page

Subscribe to our Blog Digest (select EMTAS)

In this blog, Hampshire EMTAS Bilingual Assistant Eva Papathanassiou reviews Mantra Lingua’s Kitabu dual-language ebook Library.

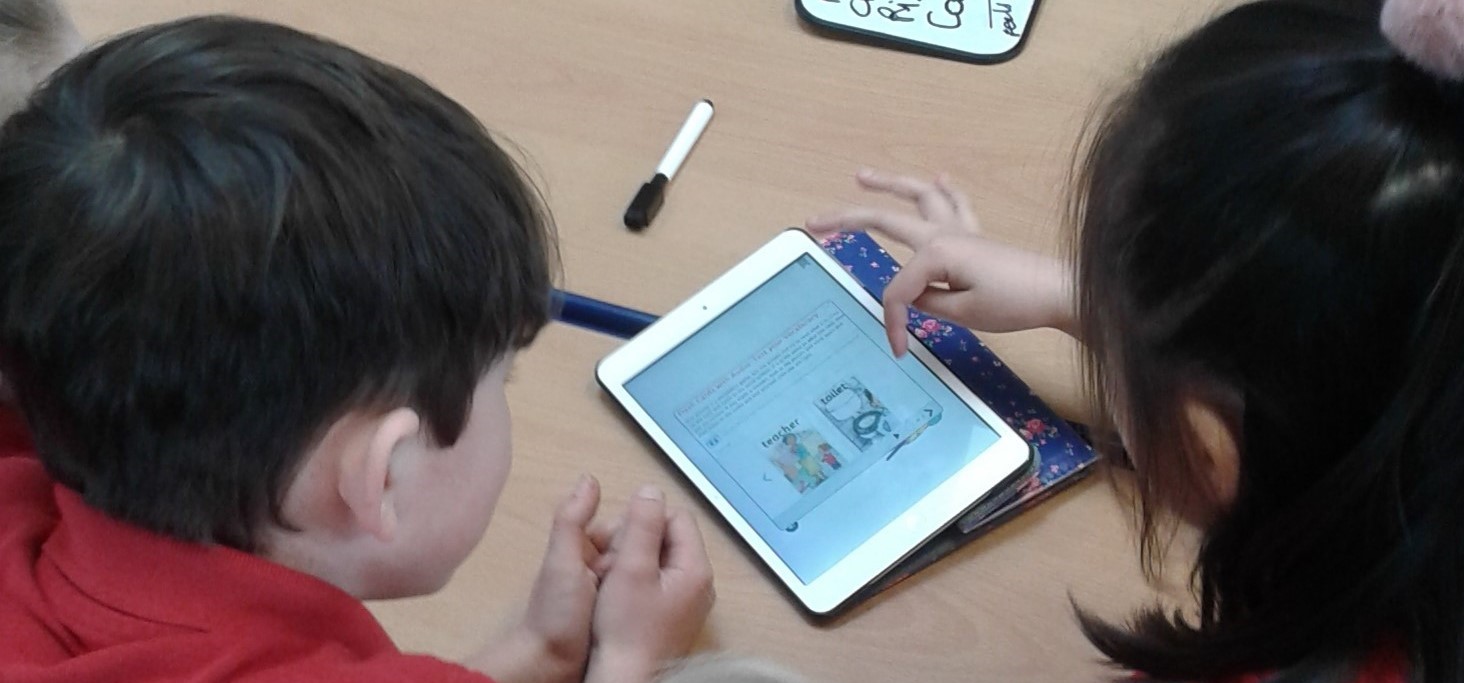

I got very excited and relieved a few months ago, when I opened my work inbox and read that I was invited to have access to an application which is literally an e-book library! Excited, because as a Bilingual Assistant, I know how any first language use, tool and resource can be extremely useful and significant for supporting children who have English as an Additional Language (EAL) to engage with the curriculum. Relieved, because this rich and diverse library would be in my hands, at any place, at any time, in less than one minute, without having to travel to our main office to get a resource or having to ask my colleagues to send to me at short notice.

I will briefly present to you this tool which is available as an app (download from Google Play or App Store) as well as through a URL on laptops and computers. I will then share with you two examples of how I have used it and why I am still so enthusiastic about it.

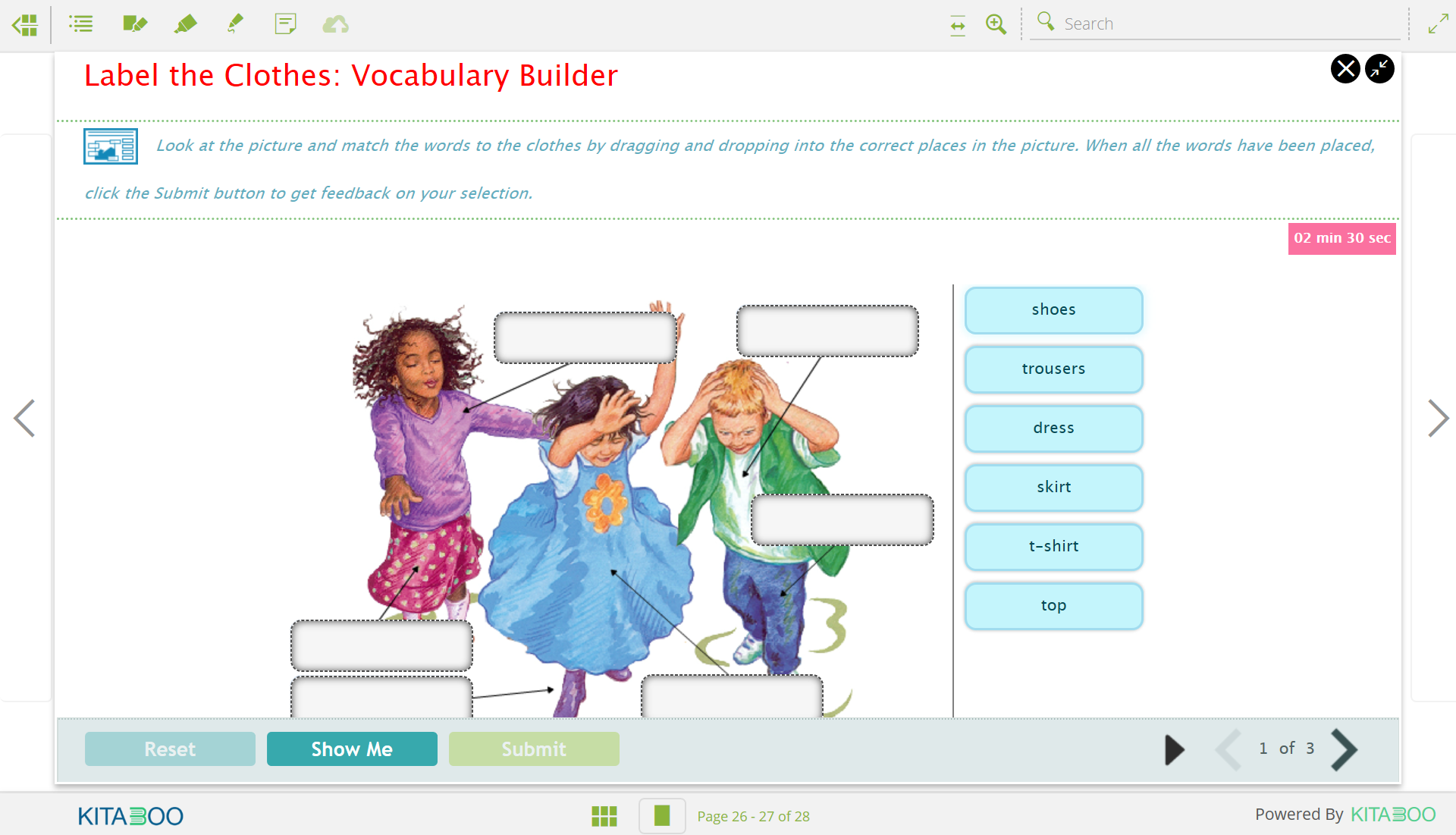

The Kitabu dual-language ebook Library by Mantra Lingua is a bilingual, interactive e-book library which gives you access to more than 550 books in 42 languages. The books are grouped by origin of language and type/genre. The majority of the books are fiction and folk stories for primary to early secondary (KS3) children. The fantastic thing about this library is that every e-book has both text and narration in two languages and different extra features. For example, you can create and share notes in any page, you can highlight a word or you can use a pen to draw, write or erase in any place in the text. You can also ‘tap around to hear the sound’ - tap around the page and hear the sounds of the illustration, making the book very vivid and appealing, especially to young children.

Most e-books contain a video of the story in English and follow on activities at the end for vocabulary and comprehension such as flash cards, labelling the parts of a picture, matching pairs, sequencing pictures and video observations matched with reading comprehension multi-choice questions. As you will read later on, I found the activities extremely useful to both EAL pupils and myself, especially for making the children feel more relaxed and confident, creating a rapport and for assessing first language literacy skills.

I first used the Kitabu dual-language ebook Library last autumn, when I visited a Primary School to meet and support a Romanian pupil in Year 2, Alexandru*, who had recently arrived in Hampshire. One important part of my job is to write an initial profile report of the EAL pupil by collecting important information about the child, their personality, their concerns and challenges, previous education, the level of their literacy in first language and their proficiency in English at the school starting stage (in partnership with the school teacher). Sharing the same language and culture makes the pupil’s initial profile creation a more straightforward task. However, someone who doesn’t share the child’s first language would find the process more challenging due to the lack of mutual understanding and immediate rapport that comes more naturally with someone who shares the same heritage. I don’t speak Romanian so I needed to use any tools and means available that would facilitate this task, but most importantly would enable the pupil and myself to get to know each other a little bit more and establish a bond, a relationship of trust. After a brief cooking activity with his class, it was time for me to get to know Alexandru better and assess his literacy skills. The Kitabu dual-language ebook Library came to my rescue and in two minutes, I had in front of me a selection of 8 bilingual books for Alexandru to choose from. Alexandru seemed very much at ease with the tablet and he happily took it from my hands to explore it. When he noticed the title of the books in Romanian, his face lit up; he chose the book Let’s Go to the Park/Hai să mergem în parc and we both started exploring straight away.

Alexandru tapped excitedly the different parts of the book and heard the narrative in Romanian and the different sounds of the illustration, scenes of a park full of children playing with their families. Slowly, he read some of the sentences in his first language and he heard the audio and me reading the same sentences in English, whilst he was pointing to the pictures and tapping to hear the different sounds. We moved on to the activities at the end, and we looked to the bilingual glossary with matching images from the book where we could both hear and read the words in both languages. Alexandru had the opportunity to learn some new English words, teach me some Romanian ones and correct my pronunciation and at the same time he felt happier, more relaxed and engaged. He also wrote some words in capital letters in his own language showing his writing ability, which seemed appropriate to his age and previous education. Alexandru also built his vocabulary further with different games when he labelled the parts of an image by dragging the correct word at the correct place and matching different pictures to words on the tablet and submitting his answers. This e-book enabled me to engage in an informal conversation with Alexandru, made both of us feel more at ease and get to know each other a little bit better while I had the opportunity to assess Alexandru’s first language (and partly English) listening, speaking, reading and writing skills.

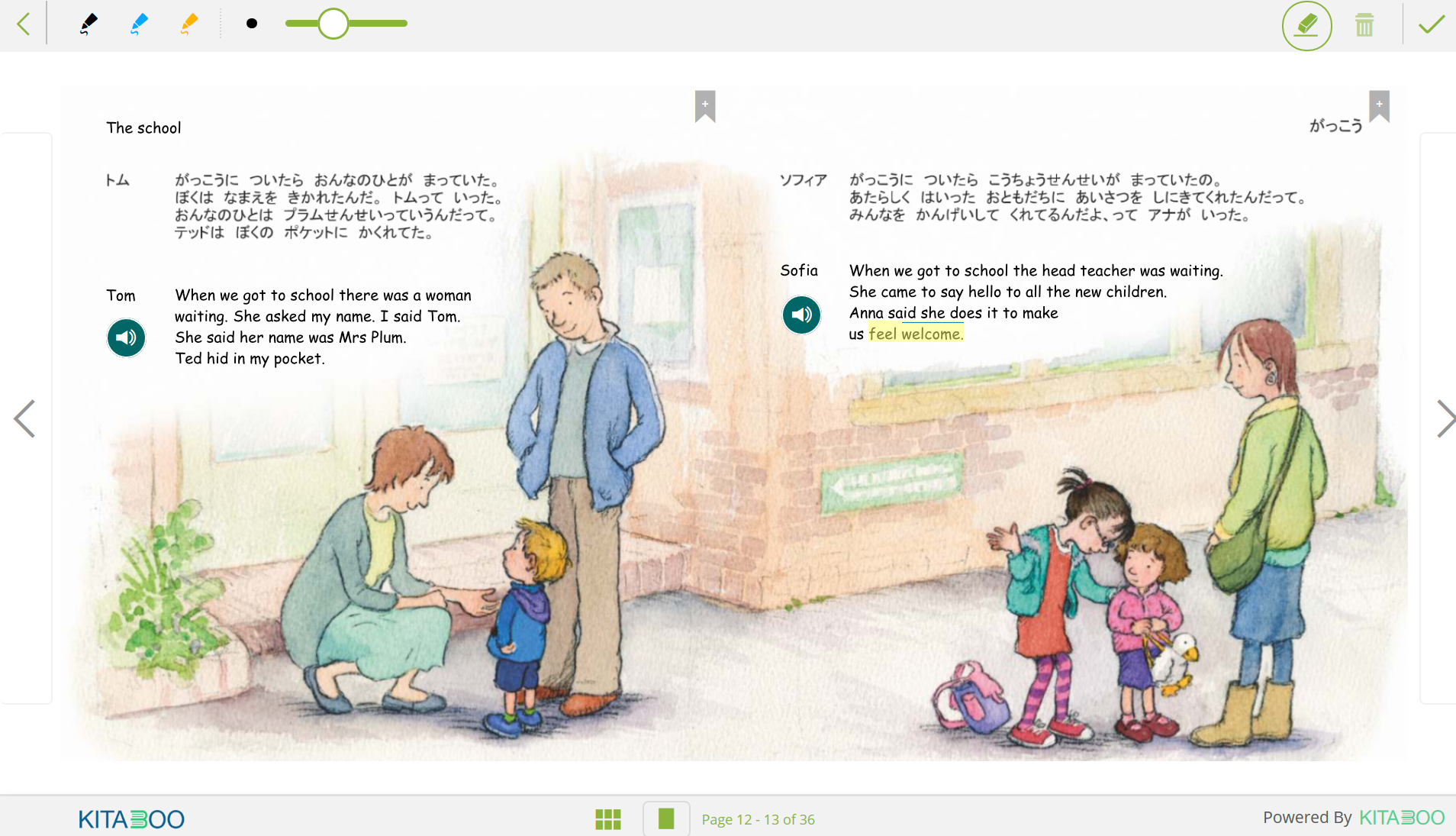

A second example where I found the Kitabu dual-language ebook Library extremely beneficial was when I was asked to take over the support of a Japanese girl in Year 2 at another Primary School after one of my colleagues left our team. Hinata* had learned to write in her first language at nursery in Japan and firstly joined the school in the summer term of the previous academic year, in Year 1. The school had very successfully used Hinata’s previous skills for various writing activities and the EMTAS department had already sent a bilingual book for Hinata to read together with her classmates. Hinata appeared rather shy when she had to speak to her teacher or in front of her class and she used one word answers or gestures for communication.

During one of my visits, I was asked by Hinata’s teacher to supervise a ‘guided reading’ group activity where Hinata and three of her friends would have the opportunity to read and discuss the bilingual book, Mei Ling’s Hiccups/メイリンのしゃっくり, lent by EMTAS as a hard copy.

Hinata appeared reluctant to read out loud in Japanese but she did read each page to herself and subsequently she happily heard the rest of the group who took turns to read the text in English. Very soon Hinata appeared more relaxed and took her turn to read parts of the text in English. Everyone was impressed with her reading skills and praised her efforts. We got into a conversation about parties and Hinata was able to answer closed questions and give one-word answers, using key vocabulary from the book i.e. balloon, party, drink. Having been exposed to the Kitabu dual language ebook Library very recently, I enthusiastically searched to find any appropriate Japanese books. I was thrilled to find Mei Ling’s Hiccups as an e-book and straight away I found the follow-on vocabulary and comprehension activities. In school, Hinata together with her classmates quickly got engaged in matching pictures to words and labelling different parts of a picture. Soon Hinata appeared much more confident to demonstrate her comprehension by tapping, dragging and listening to the questions, very often volunteering her answers and at the end we went back to the book text and Hinata heard parts of the story in Japanese and read several phrases in English.

Last week, I visited the Primary School again for Hinata’s follow up visit. I was looking forward to seeing and supporting Hinata again and I remembered how much Hinata together with her classmates had enjoyed the bilingual book and its linked Kitabu activities, the first thing I did was to download another Japanese e-book from the app.

Hinata was joined by three other children and all together we went to the school library to read the new e-book, Tom and Sofia start School. Hinata was again hesitant to read in her language but she was very happy to listen to the text in Japanese, read some pages to herself and the rest of the group seemed excited to hear the story in a different language and took turns to read or hear the audio of the text in English. Very often after this activity, they asked Hinata questions like ‘is this how you say the word cool?’ repeating the last word they heard from the Japanese audio. Hinata replied by ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and she was also able to answer a few comprehension questions with one word answers with no hesitation. Afterwards, we watched the animated video of the story and we proceeded to the Video Observations follow on activity where you answer comprehension multi choice questions based on what you have just seen. Hinata’s confidence grew and very soon, she volunteered to answer the questions by choosing the correct answer on the tablet, take her turn to read small portions of the text in English together with her peers and participate in the other activities such as labelling the parts in a picture or matching pairs of images and words.

I used the Notes feature to write a comment on where and how Hinata read in the book and the children used the pen to circle different words in the e-book to demonstrate their comprehension. We highlighted more tricky words or phrases like ‘feel welcome’ and the group discussed what the phrase meant with examples. They also had the opportunity to listen to and read the definition of the word ‘welcome’ in English from an e-book. Hinata took part in all group activities contentedly and apart from learning through a new story and its key vocabulary, she was enabled to demonstrate her listening and reading comprehension and reading out loud skills confidently in front of the small group of her peers. In addition, she paid attention to the given instructions in English (read by me) or heard by the activity audio and followed what she needed to do together with her classmates, proud when she submitted a correct answer. At the end of the session, the group talked about their ‘special friends’ at home, pets or toys and Hinata told everyone that hers was a bunny.

Knowing how important it is for EAL pupils to continue using their first language in school and at home, the Kitabu dual-language ebook Library with text and audio in two languages, interactive activities and animated stories gave me an excellent opportunity to create a rapport with children who do not speak English or Greek (my own first language) and enabled me to assess their first language and English skills, through story-telling, informal chats, videos and games. Both Alexandru and Hinata felt more confident and engaged, happier to express themselves and participate, something more evident in a group setting.

The Kitabu dual-language ebook Library with its extensive bilingual library is another excellent tool for enriching children’s learning environment by use of their heritage language; something essential for confidence-boosting, self-expressing, demonstrating academic knowledge, studying more efficiently and independently and most importantly maintaining their culture and sense of identity.

*pseudonym

Find out more about Kitabu dual-language ebook Library (Mantra Lingua is offering parents of learners of EAL free access to the Kitabu dual-language ebook library until the end of August - see attachment for details)

Visit the Hampshire EMTAS website

Congratulations

to Eva who was appointed as our new Bilingual Assistant Manager since writing

her blog.

The Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisors have been supporting schools to complete the EAL Excellence Award for over a year now. Many schools have successfully earned their Bronze and Silver awards and are already working hard to achieve the next level up. Working with schools to drive EAL practice and provision forward through the EAL Excellence Award has highlighted areas of support which the EMTAS Teacher team has been keen to address.

One particular aspect of EAL good practice which many schools have had to consider is the use of first language as a tool for learning. Whilst most could confidently say that pupils felt comfortable speaking their languages at school (a feature evidenced at Bronze level), EAL co-ordinators felt that pupils could be better encouraged to use their languages to access the curriculum in the classroom (a feature evidenced at Silver level). In response to this, the EMTAS Teachers have been working closely with their schools to introduce ideas and strategies to support this and they are now keen to share their work with the EAL community.

Discover our brand new materials which consist of a narrated animation (below) with supporting material you will find attached to this blog: a transcript, activities based around the animation and an aide-mémoire summarising key strategies. Our work is still ongoing with a brand new piece of EAL elearning currently under development – watch this space!

Visit the Hampshire EMTAS website

Subscribe to our Blog Digest (select EMTAS)

By Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Jamie Earnshaw

A huge congratulations to all students who achieved a GCSE in a Heritage Language this summer! EMTAS supported 48 students with GCSEs in Arabic, Chinese Mandarin, German, Greek, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Russian and Turkish.

Here are all the fantastic results

achieved by students we supported:

GCSEs graded 9-4

|

Language |

9 |

8 |

7 |

6 |

5 |

4 |

|

Arabic |

2 |

1 | ||||

|

German |

1 |

|||||

|

Greek |

1 |

1 |

||||

|

Italian |

4 |

3 |

||||

|

Mandarin |

3 |

1 |

||||

|

Polish |

7 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Russian |

2 |

1 |

2 |

|

||

|

Total |

18 |

9 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

GCSEs graded A*-C

|

Language |

A* |

A |

B |

C |

|

Portuguese |

2 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

|

Turkish |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Totals |

3 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

As you can see, students did extremely well this summer. Many students achieved the top grades and there were individual stories of success across the board too, including one student who did really well who was previously referred to EMTAS when in primary school and was later diagnosed with SEND with difficulties in reading and writing. Even with an uneven profile of skills across Reading, Writing, Speaking and Listening, with support and hard work, students can still succeed and achieve a grade at GCSE. Also do note that we offer an initial one session package of assessment to help determine if a student is ready for the GCSE.

Many of the students we supported this year were in Year 11 - we wish those students good luck with their next steps! No doubt the Heritage Language GCSE will be a bonus for those students to show to future colleges or employers. Do bear in mind though it is not necessary to wait until a student is in Year 11 to enter them for a Heritage Language GCSE but sometimes the themes of the exams are better-suited to older students (so perhaps most suitable for students in Year 9 onwards).

Visit

the GCSE page on our website for more information about the

GCSE packages of support we

offer to help prepare students for Heritage Language GCSEs. When you have

decided which package you want, ask your Exams Officer to complete the GCSE

Support Request and GCSE

Agreement forms and return them both to Rekha Gupta

using the address details provided on the GCSE Support Request form (by the

deadline of the 1st March 2020).

We look forward to working on Heritage Language GCSEs with you and your students this academic year!

By Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Jamie Earnshaw

The early morning birdsong, lighter evenings and even maybe some sunshine peeping out from behind the clouds…this can only mean one thing: exam season is upon us.

This academic year, EMTAS Bilingual Assistants have supported over 50 EAL students in schools across Hampshire, and the Isle of Wight, to help them to prepare for their Heritage Language GCSEs. We have supported students who speak Arabic, Cantonese, Polish, Portuguese, Russian and Turkish, to name just a few. I’m sure that both staff and students will sigh a breath of relief to get to the end of the exam season this year!

Whilst we all know how stressful the exam season can be, upon receiving their results, many EAL students are given such a boost of confidence. It may well be an EAL student’s first experience of exams in this country and what better way than to acclimatise to the anomalous experience of sitting in an exam room than doing so in a subject they know well.

Nevertheless, just because a EAL student has grown up in an environment in which their first language has always been spoken, or they have had formal education in their home country, it is so important that we do not take for granted that students necessarily have the skillset to be able to take a GCSE exam in a Heritage Language without support. Do students have the skills across all aspects of the exam, speaking, listening, reading and writing, in order to be able to access the exam with confidence?

Having been brought up in the UK, where I spoke exclusively English, it was not just enough for me to turn up to the exam hall and proclaim my readiness for the English Language exam. In fact, I had 4 lessons each week, during my GCSE schooling years, in which I developed, improved and focused my language skills across speaking, listening, reading and writing. There was also the need to learn how to tackle the exams. How am I expected to answer the questions? Which skills do I need to display? What am I being assessed for?

It is essential for EAL students to have the same opportunity to have those niggling questions answered and to receive appropriate support when completing a Heritage Language GCSE. Attempting and receiving feedback on past papers and rehearsal opportunities for the speaking test are vital. It is also worth remembering that the papers are designed for non-native speakers, so the tasks are set in English. Therefore, for a newly arrived student with very little English, time might be needed to develop skills in English to a level in which they are able to access the questions or, at the very least, get used to the target question vocabulary used in the papers.

Once these initial hurdles have been crossed, the benefits for students really are immeasurable. Often, pupils achieve very good grades in their Heritage Language GCSEs and this can be a bonus when they are applying for college places or apprenticeships. It also gives students that experience of completing a GCSE examination, which, if they do earlier than Year 11, will help to ease any worries about what the experience of sitting an exam is actually like when it comes to perhaps those more daunting subjects like English, Maths and Science.

Visit the GCSE page on our website for more information about the EMTAS GCSE packages of support available to help prepare pupils for Heritage Language GCSEs. When you have decided which package you want, ask your Exams Officer to complete the GCSE Support Request and GCSE Agreement forms and return them both to Rekha Gupta using the address details provided on the GCSE Support Request form (by 1st March 2020).

Good luck to all those students (and staff) anticipating GCSE results this summer!

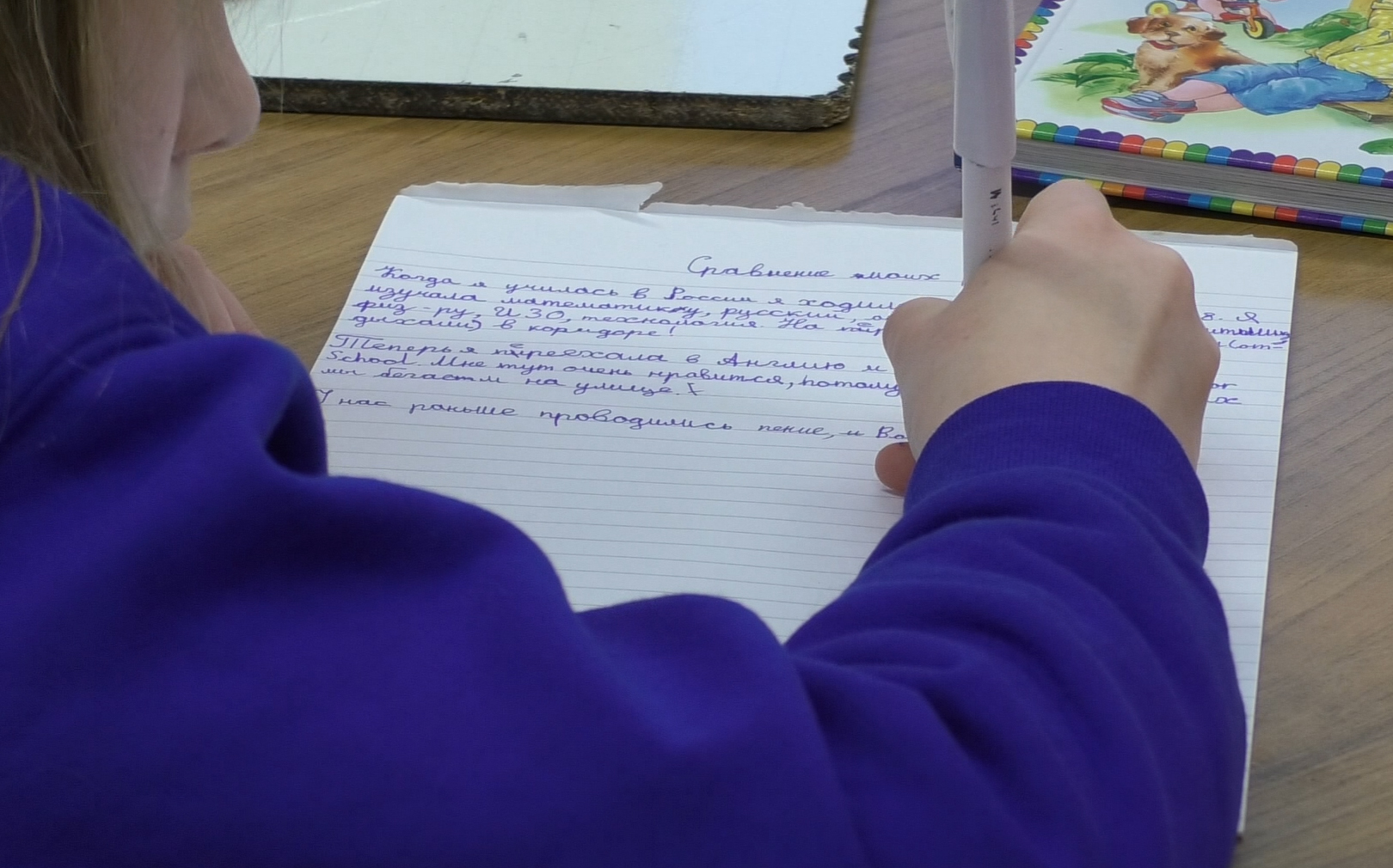

By Hampshire EMTAS Bilingual Assistant Luba Ashton

It can be very challenging for many school practitioners to start working with new EAL arrivals who have either very limited or no English language skills. In this situation, the school staff may have a lot questions and many of them can be about the pupil’s native, or first language skills:

Is the child speaking at an age appropriate level?

How proficient is this pupil in reading and writing?

Is the pupil working above or below age related expectations?

It is very important to find the answers to these basic questions sooner rather than later to start developing the pupil’s English skills with support of their first language prior knowledge and skills.

The best solution is always to invite an EMTAS bilingual assistant to carry out an assessment and get important insight in pupil's educational and cultural background. But when EMTAS are not immediately available, is there anything the school practitioners can do in the meantime, even when they do not share the pupil’s language?

It may sound surprising - but the answer is yes.

This is made possible with the help of the First Language Assessment E Learning resource, created by EMTAS. Using this E Learning tool, practitioners are given advice about how to carry out an assessment of pupil’s skills even in an unfamiliar language.

This resource will explain how to make judgement about reading proficiency; clarify comprehension, notice various features such as accent, intonation, expressing punctuation. It will also help to identify specific strengths and weaknesses in writing; handwriting, quantity, punctuation, self-correction etc.

The E Learning resource provides a practical step by step guide. It is structured into a few parts and gives very detailed instructions on how to assess listening, speaking skills and also reading and writing skills for pupils who are literate in their first language.

Other important steps explained are:

how to prepare for the first language assessment

how to guide and encourage the pupil

best practice to conduct the assessment

how to interpret the outcome of the assessment

how to use the results to further support the development of the pupil’s English skills.

The E Learning resource uses a real life case study of a new arrival Year 6 pupil, Maria. She is a native Russian speaker. The videos provide very useful guidance and enjoyable viewing. It is amazing how much you will be able to say about Maria’s Russian skills without being able to speak Russian!

The materials also provide users with a variety of interactive tools, a check list and links to other resources to support the assessment together with explanations of how to use and where to find them. It is set out to enable the practitioner to make an informed decision as to whether the pupil works at an age appropriate level and help highlight any potential issues.

Feedback from practitioners using this resource has been very positive and I am sure it will be a valuable support for the early assessment of EAL pupils. Visit Moodle for more information.