Site blog

Sarah Coles shares the third instalment of a journal-style account of her reading for the literature review and methodology chapters of her PhD thesis.

Week 5, Autumn 2018

Last time I focused on sequential and simultaneous bilingualism with a light touch on the Critical Period Hypothesis, specifically referencing the age at which one starts learning an additional language, a cause for personal lament. I mentioned how there is a general difference between early starters and late starters, with the acquisition of phonology being the key area in which a difference can be discerned. Apart from that, the notion of there even existing a Critical Period is open to debate, so the jury’s still out. Undaunted I will keep up my efforts, practising asking for things in Turkish when in France.

There are, of course, various factors that are important in second language learning and in this instalment I will talk about two more: aptitude and attitude/motivation. First to aptitude, and the literature reveals that…wait for it…some people are better at learning a second language than others. Ground-breaking stuff you’d never have thought of for yourself, eh? Anyway, in the 50s and 60s, aptitude was a popular area of study and there were many tests developed, each designed to assess language aptitude. These were largely geared towards formal second language learning in the 1960s classrooms of the UK, where students conjugated verbs, did precis and dictation and learned lists of vocabulary (in fact exactly how I was taught French in the 1980s) but rarely – if ever – used the new language to communicate with others. How weird is that? Anyway, when teaching practice evolved to include experience of actual communication (must’ve been after I left secondary school), aptitude testing fell out of favour. There ensued a tumble-weed period of about 30 years until the debate bump-started again in the 1990s when working memory was put forward as a key component of aptitude, conventional intelligence testing having become a subject of much controversy. The net result has been to propose language learning aptitude needs to be redefined to include creative and practical language acquisition abilities as well as memory and analytical skills. Mystic Sarah predicts the conclusion will still be that some people are just better at it than others but that a lot more hot air will have been generated along the way.

Now, if you’re all still keeping up, to attitude and motivation. As you might presume if you give it 5 minutes’ thought, these are difficult things to measure. Gardner and Lambert (1972) helpfully distinguished integrative motivation and instrumental motivation. These go as follows. Integrative motivation is based on an interest in the second language and its culture and refers to the intention to become part of that culture. I wonder if by this they were really talking about assimilation, given they were writing in the 1970s, but that aside they developed tests to measure motivation and attitude. These included factors such as language anxiety, parental encouragement and all the factors underlying Gardner’s definition of motivation. A sort of self-fulfilling prophecy, then. For Gardner, the learner’s attitude is incorporated into their motivation in the sense that a positive attitude increases motivation. This is not always the case, some astute observers note, citing by way of an illustrative example Machiavellian motivation in which a learner may strongly dislike the second language community and only aim to learn the language in order to manipulate and prevail over people in that community. They do like to quibble, these academics.

Instrumental motivation is all about the practical need to

communicate in the second language and is sometimes referred to as a ‘carrot

and stick’ type of motivation. The learner wants to learn the second

language to gain something from it. I can see the carrot here, but where

the stick comes in is less clear, unless it means putting in the effort

required to make progress. Back on planet earth, it is often difficult to

separate the two types. For instance, you might be in a classroom

learning a second language and you might have an integrative motivation towards

your progress in acquiring the second language. You might, for instance,

yearn to have a Spanish boyfriend and fancy going off to live in Madrid or

Barcelona to find him. But you might at the same time have an

instrumental motivation to get high grades in order to ensure you can get onto

the A level Spanish course next year, just in case he turns out to be nothing

more than a pipe dream and you need to rethink your strategic timescales.

People more recently engaged with this aspect of the discussion suggest this

dichotomy (integrative/instrumental) is a bit on the limited side. They

put forward ideas such as social motivation, neurobiological explanations of

motivation, motivation from a process-oriented perspective and task

motivation. So nowadays motivation is seen as more of a dynamic entity,

in a state of constant flux due to a wide range of interrelated factors.

That said, motivation is a good predictor of success in second language

learning. Probably.

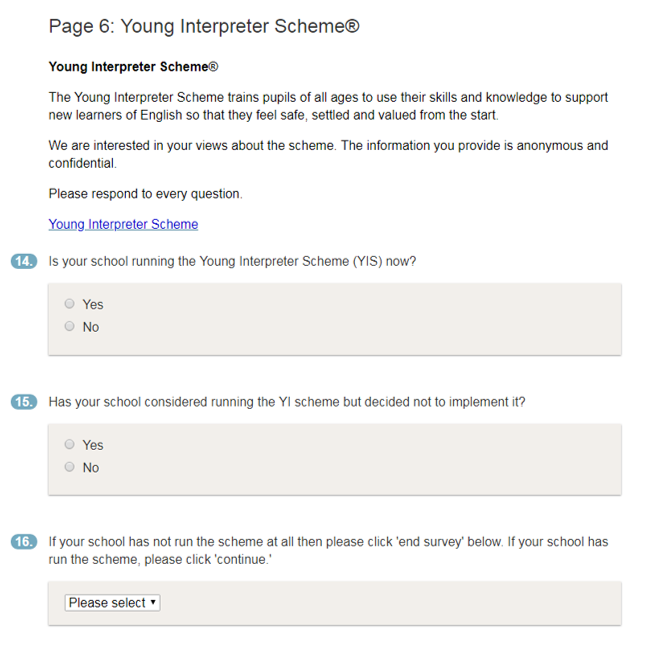

By Debra Page, Masters candidate at the University of Reading

Hi readers. If you’ve not read about me in the Young Interpreters Newsletter, my name is Debra Page. I am conducting research on the Young Interpreter Scheme under the supervision of the Centre for Literacy and Multilingualism at the University of Reading and with Hampshire EMTAS as a collaborative partner. This is the first time the successful scheme will be systematically evaluated since it began 10 years ago. I have worked in research and as an English as a Additional language teacher since graduating with my psychology degree. Now, I am completing my Masters in Language Sciences before starting the PhD. My Masters research dissertation is looking at staff experiences of the Young Interpreter Scheme with a specific focus on motivation for participation in the scheme, views around teaching pupils with EAL and effects of running the scheme on children, staff and schools.

After months of behind the scenes work from the team, a questionnaire has now gone live! The team and I encourage as many staff as possible to complete the questionnaire. This includes people who are running the scheme, who aren’t running the scheme, and staff who work with children with EAL. This anonymous online questionnaire should take around 15 minutes to complete and will allow myself and Hampshire EMTAS to discover what you really think about the scheme, your experiences of participation, and working with children with EAL. Finding out your views in running the scheme (or not) will help EMTAS improve and expand it, plus you will be helping to shape its future.

If you haven’t met me yet, I will be at the Basingstoke Young Interpreters conference on 28th June. If you have any questions about the questionnaire, please email me – debra.page@student.reading.ac.uk.

I hope you choose to help by completing the questionnaire. Please spread the word and share the link!

Sarah Coles shares the second instalment of a journal-style account of her reading for the literature review and methodology chapters of her PhD thesis.

Week 3, Autumn 2018

Week three of the PhD experience and this time I dwell on second language acquisition in early childhood and whether or not there is a difference in one’s eventual proficiency in a language due to acquiring it simultaneously or successively in early childhood. Simultaneous bilingualism is where 2 (or more) languages are learned from birth, ie in a home situation where both languages are more or less equal in terms of input and exposure, a child would develop 2 first languages. I am not volunteering to try and explain this to the DfE, who seem thus far only able to comprehend home situations in which children are exposed to just the one language, but maybe some followers of this blog don’t find it such a strange notion. If so, then perhaps they are in the company of researchers who suggest children growing up in this sort of situation proceed through the same developmental phases as would a monolingual child, and they are able to attain native competence in each of their languages. I personally think there are many variables at play in any teaching and learning situation, things like motivation, confidence, opportunity, resilience and the like, and they all play a part in our lifelong learning journeys. I also think the concept of “native competence” is problematic. What do we mean by that term? How are we measuring it? Do we mean just listening and speaking or reading and writing as well? What about the different registers – does – or should - fluency in the language of the streets count for as much as academic English delivered with Received Pronunciation? Who says so? Then I consider the many monolingual speakers of English I have known; they are not all comparable in their competence in English, despite experiencing a similar sort of education as me, many of them over a similar period of time. Thus ‘native competence’ is not a fixed, immutable thing – in an ideal world, you don’t stop developing your first language skills when you meet the ARE for English at the end of Year 5, do you? ‘No’, I hear you chorus, clearly agreeing with me that it’s a moveable feast. So now even the yardstick implied by the term “native competence” is starting to look a bit flimsy and unfit for purpose. Funnily enough, it wasn’t nearly so problematic until I started all this reading.

Moving swiftly on: if, however, two or more languages are acquired successively, a very different picture emerges from the literature. It has been argued that in successive bilingualism, learners exhibit a much larger range of variation over time with respect to the rate of acquisition as well as in terms of the level of grammatical competence which they ultimately attain. In fact it is doubtful, asserts a guy called Meisel writing in 2009, that second language learners are at all capable of reaching native competence and he says the overwhelming majority of successive bilingual learners certainly does not. Controversial or what? And Meisel is not on his own here; there are many people who agree with the “critical period hypothesis” which essentially boils down to the idea that there is an optimal starting age for learning languages beyond which, and no matter how hard you try, you will never become fully proficient (whatever that means). Johnson and Newport (amongst others) say this age is between 4 and 6 years - which makes me feel a bit downhearted, like I have completely missed the bilingual boat here. Curses.

It all makes for a rather depressing prognosis for older EAL learners, those late arrivals for instance, yet we know from other research that those of our EAL learners who’ve had long enough in school in the UK can achieve outcomes at GCSE that are comparable with their English-only peers, and this can only be a Good Thing, opening doors for them as they go through their teens and into adulthood. For next time, I will try to read something more uplifting, though I expect whatever that turns out to be it will raise more questions than it answers. Keep tabs on the journey as it unfolds using the tags below.

Sarah Coles shares the start of her PhD journey with the first two instalments of a journal-style account of her reading for the literature review and methodology chapters of her thesis. She is planning to research the language learning journeys of UK-born EAL learners as they enter Year R but before entering the field, there are books and articles to be read and planning to be done.

Week 2 of Term 1 (2018-19) and the summer has faded in more ways than one, which coincides with an interesting bit of a book I have been reading for my PhD. The book is about Second Language Acquisition and makes the point that most research into this has a focus on learning the new language. While this is of course interesting with many, often competing, views vying for attention in the literature, the authors suggest that language attrition – or ‘forgetting’ – is equally interesting. They say that all our languages form part of a complex, dynamic system in our brains that changes continuously and they put forward a simple rule which states that information we do not regularly retrieve becomes less accessible over time and ultimately sinks beyond our reach. In relation to our languages, these are in a constant state of flux, they argue, depending on the degree of exposure we have to each. Talking to colleagues about this in the EMTAS office, they said they had noticed changes in their own languages over time. Kamaljit talked about how her ability to write in Hindi has decreased due to lack of use, whilst Ulrike and I had both experienced difficulties with word retrieval and with one language affecting the other in different ways. For instance sometimes, because of immersion in Turkish all those years ago, I would respond in Turkish to members of my immediate family who don’t speak the language when I went home for a holiday. They were grateful that this passed fairly rapidly, though I observe my languages have been shuffling around in my mental filing cabinet ever since. Mostly, English sits at the front and comes out first, Turkish is a bit further back but in front of French, pushing French out of the way when I am in France much to the bemusement of the French – the majority of whom don’t speak Turkish either.

Week 3 of term 1

Alongside the day job, I have carried on reading for my PhD studies and my focus this week has been on qualitative research methods. One thing I need to consider carefully is my own impact on the situations I will be researching because even if I am only there to observe, this in itself will influence not only what happens but also how I interpret what I see. Clearly in a classroom situation you cannot see absolutely everything that happens, never mind be able to record it all in handwriting that you can read back afterwards. There will be much that you don’t see at all, and also much that you do see but that you don’t record – which isn’t to say it’s not useful or relevant to the area of research, just that there will be inevitable casualties due to the pragmatic aspects of what you’re able to do as the researcher. Anyway, the long and short of it is that researcher bias is something I will need to be aware of as according to several different authors, you can’t remove it from the equation. Rather, you need to be aware of your point of view, your previous experiences and prior knowledge and how these things colour the way you see and hear and interpret events in order to manage the impact of your own bias on your research. It is interesting to me to consider too how language and cultural differences might impinge on methods like interview, and there is a lot to think about when you are planning to use this as a tool to elicit data from people. You could, for instance, have a set of predetermined questions and you could just ask people those. Or you might find this too interrogative a way of doing an interview which just doesn’t fit with what you are trying to achieve – which in my case is a full, rich picture of people’s lived experiences and views. So I am thinking about a more flexible approach, possibly around doing some mapping of languages, people, communities and the like while people talk, which won’t look much like the sort of interview I mentioned first but will hopefully give me the sorts of data I am looking for. I have yet to read the chapter on coding, so there is a chance I may change my mind about this. Keep tabs on the journey as it unfolds using the tags below.