Site blog

By Astrid Dinneen

In a previous blog, Hampshire EMTAS Team Leader Sarah Coles and Specialist Teacher Advisor Astrid Dinneen considered ways of supporting Hatice, a Turkish-speaking pupil in Primary school working within Band A of the Bell Foundation EAL assessment framework. In this blog, we catch up with Hatice and explore EAL practice which may support her as she continues her journey towards full academic proficiency.

It’s been nearly a year since we last wrote about Hatice, a new-to-English pupil literate in Turkish who joined Year 5 in her first UK school. Avid readers of our blog will remember that her teacher chose to put in place EAL-friendly strategies to help her access the curriculum alongside her peers. For example, a home-school journal was embedded so Hatice could discover, research and translate vocabulary in advance of lessons. In addition, grouping was considered to ensure she was exposed to sophisticated speakers of English as part of a trio. Finally, another powerful way to help Hatice engage with her learning in class was to build in opportunities for her to use her first language. She used translation apps downloaded on the class iPad and wrote in Turkish to annotate handouts as well as to demonstrate her learning. This resulted in Hatice feeling included and motivated to take part in a broad and balanced curriculum.

Fast forward to now, Hatice is in Year 6. She’s working securely within Band B and she is starting to demonstrate features of Band C, particularly with listening and speaking. Hatice is a popular member of the class. She has many friends and appears very chatty on the playground. She has formed good relationships with a range of adults in the school with whom she also enjoys conversations about her activities and the things she enjoys doing at home and at school. Hatice listens carefully in class and regularly takes part during lessons to contribute to whole class discussions and collaborative group activities. Her home-school journal is still in place hence she continues to be familiar with vocabulary linked to her subjects. She also has a good go at using her keywords in her contributions. Hatice feels more confident about her speaking in English hence she is increasingly attempting to write in English. However her teacher has noticed that whilst pre-rehearsing vocabulary in advance has helped Hatice become familiar with language at single word level, she appears to need further support at sentence and whole text level.

So what now? How can her teacher build on Hatice’s success? What does EAL practice look like for learners who are beyond the early stages of learning English?

It takes a long time for pupils to acquire both informal and more academic language – anything between 5 and 10 years. To make further progress pupils will continue to need support along the way through amazing teaching and learning. In fact Hatice’s teacher should feel reassured in the knowledge that keeping going with EAL-friendly strategies rather than a decontextualised English-first approach is recommended, even after the first few months. This means persevering with practice already in place for Hatice eg inclusion in the language-rich classroom, discovering vocabulary in advance, grouping with good language role-models and using first language as a tool for learning is still recommended.

With the latter in particular, pupils embarking on Band C will still benefit from reading texts in their first language. Technology to support this continues to evolve – colleagues are now encouraging the use of Google Lens and Immersive Reader which both allow pupils to read and listen to translations instantaneously. And whilst pupils like Hatice may increasingly produce their writing in English, it is important for opportunities for first language use to still be part and parcel of teachers’ planning. For example, Hatice may be planning her writing in Turkish and later completing it in English. Encouraging the use of first language at the planning phase reduces the cognitive load, helping pupils keep momentum for the writing phase. Likewise, routinely using translation tools will undoubtedly also continue to support pupils on their journey to full academic proficiency.

New-to-English pupils tend to make rapid progress initially, particularly from Band A through to Band B. This may give us the illusion that they require little EAL support after this point. However, after this initial stage it isn’t uncommon for pupils to reach a plateau as they embark on Band C ie ‘Developing Competence’. This is usually because ‘pupils with advanced fluency in spoken English are often left without support because their conversational competence masks possible limited vocabulary for curriculum purposes’ (Cummins, 1999).

So what else can Hatice’s teacher put in place to help her choose the best ways to express herself?

Let’s explore whole class strategies that will not only benefit Hatice but also her peers, whether they are EAL or not. Her teacher may like to build on the pre-reading of keywords happening at home and plan in whole class word level activities such as bingo games, word races, dominos etc. For example, imagine that a final outcome for a whole-class topic was for pupils to write a balanced argument on whether climate change is natural or man-made. Hatice may have talked about climate change in Turkish at home and translated tier 1 and tier 2 keywords such as hemisphere, scientists, sea levels, etc. in advance. Back in class, the whole class could also focus their attention on this language. A word race for example would see pupils work in pairs or trios to find definitions hidden around their classroom and match them to the keywords. Alternatively, a bingo game would see Hatice’s teacher read out the definitions for pupils to cross off their card (bingo card generator apps can help resource this).

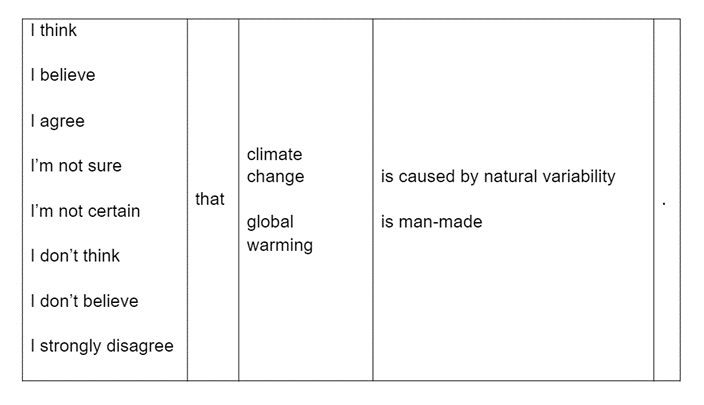

Having focussed pupils’ attention on subject specific language at word level, Hatice’s teacher could support language at sentence level. Sentence structure can be modelled and made explicit thanks to substitution tables - an extremely useful scaffolding tool to support speaking as well as writing. A substitution table is a simple frame which allows the learner to follow the correct syntax in a sentence whilst retaining autonomy over the choice of words. To continue with our theme of climate change, a substitution table could help Hatice (and others in her class) to express her views using more formal language, aided by an interactive opinion line activity:

As for modelling whole paragraphs and longer pieces, Hatice and her class could be provided opportunities for listening and speaking to prepare themselves for writing. Dictogloss lends itself well to this as a What A Good One Looks Like (WAGOLL) activity. In Dictogloss, pupils listen to a pre-prepared model text and take notes. Then they use the language they’ve heard to work with their peers (first orally then in writing) to recreate a similar piece. The end product is typically a piece of writing which includes some of the language and structures used in the model, but is not an exact replica. Dictogloss is an opportunity for pupils to hear a model that includes all the subject specific vocabulary, ideas and other things covered in class, and then to collaborate on using these same components to produce a cohesive piece of writing in keeping with the target genre.

To see what Dictogloss might look like in practice, readers can join one of our online network meetings. We will discuss the steps for Dictogloss and give a demonstration linked to our theme of climate change on January 10th and March 27th. If you cannot wait that long, why not talk to your EMTAS Teacher Advisor about whole staff training? You can also liaise with the English HIAS team to find out how EAL strategies can be woven through the English Learning Journey. For further resources, check our Guidance Library on Moodle and visit the HIAS team’s own platform.

Hatice is pronounced /hætidʒe/

written by Chris Pim, Hampshire

EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor

How to use computer games to enrich the curriculum and raise standards in reading and writing for all pupils, including more advanced learners of English as an additional language (EAL)

Introduction

Most pupils have direct experience of playing computer games, whatever their linguistic or cultural heritage. Minecraft, you may be aware, is one of the most successful games of all time. So how could you capitalise on the interest in digital gaming to engage your learners and develop approaches that can raise standards across the curriculum?

Using computer games for language learning across the curriculum – some considerations

Not all computer games are created equal – to coin a phrase. Games that are specifically designed for education, such as English language learning games, may not be that successful because pupils realise that they are no more than thinly disguised tests and don’t respond positively to them.

In an educational context the best games are immersive; the player inhabits a realistically rendered 3D world influencing a narrative- rich storyline through the actions of their character/avatar. From a learning perspective, especially for EAL pupils, professionally produced computer games contain clear graphics, authentic storylines, audio narration/music and rich texts that provide a clear context and make meaning explicit. Some also provide obvious links to the curriculum such as through historical, geographical and scientific settings and scenarios.

You also need to be aware that all marketed computer games are subject to an age rating to determine their appropriateness for children and young people (Pegi). This is an important factor in determining the type of computer game that you might choose to use with your pupils.

As you read this article you may already have ideas for suitable computer games. However you might like to consider any of the following: The Myst series, Minecraft Storymode, Syberia, The Longest Journey, Tintin - Search for the Unicorn, The Room series and Amerzone.

Curriculum opportunities

There are numerous opportunities for developing thinking, talking and writing around computer games. For example, there is obviously merit in allowing pupils to play the game in pairs/groups as the quality of discussion will benefit EAL learners as they work alongside supportive peers. There is also tremendous potential in playing parts of the game as a whole class, projecting game play onto a large digital display. One pupil plays the game and peers suggest where to look, which objects to interact with and generally help to decide on particular courses of action at major decision points. Pupils can also debate particular courses of action. This all helps to develop more academic types of language that will improve written outcomes.

Playing a computer game from start to finish won’t be possible. But the game can be moved on by playing video game walk-throughs sourced from the internet. Featured texts within the game can be used as the basis for EAL-friendly activities; vocabulary-building games, Directed Activities Related to Texts (DARTs) and collaborative writing tasks like Dictogloss.

When playing computer games it is immediately apparent how fruitful the medium is for developing writing within different text types - for example, encouraging descriptive writing around realistic settings and well-defined characters. The format also encourages learners to produce recounts of game play sessions. Finding solutions to puzzles and making progress through the game provides opportunities for instructional and explanation-based texts. Students can discuss/argue the relative strengths and weaknesses of any particular game or perhaps the appropriateness of its age-rating from the perspective of a player or parent. Pupils could also write computer game reviews.

Why not also challenge your pupils to create persuasive videos to advertise a chosen computer game? Using professionally produced video game adverts sourced from the internet you can demonstrate persuasive techniques, such as rhetorical questions, repetition, lists of three, hyperbole etc. Next, using images and video captured from their chosen game, encourage pupils to collaborate on the production of a promotional video using iMovie’s Trailer feature. You will find this activity is especially beneficial for more advanced EAL learners as it acts as an intermediate scaffold for writing persuasively.

As you can see there are many ideas for integrating computer games into the classroom to improve the reading and writing skills of your more advanced EAL learners alongside their peers. So, what’s stopping you? You won’t be disappointed with the outcomes!

To read a research case study focussed on using immersive games to improve the writing of more advanced EAL learners visit: https://eal.britishcouncil.org/eal-sector/eal-and-immersive-games