Site blog

This blog is about a collaboration between Olha, an EMTAS Bilingual ELSA (B-ELSA) and Hannah, one of two school-based ELSAs at Fairview School. Working together, they provided emotional literacy support to Yehor, a child from Ukraine, when he was in Year 2 and again when he was in Year 3. In January 2025, EMTAS Team Leader Sarah Coles visited the school with Olha to talk to Yehor about his experience of that support.

Children from Ukraine in Hampshire schools

Most of Hampshire’s Ukrainian children came to the UK under the ‘Homes for Ukraine’ scheme following Russia’s full-scale invasion of their homeland in February 2022. As we’ve got to know them, we’ve learned they are linguists, mathematicians, musicians, physicists, dancers, artists, gymnasts, chess players and poets. And they are children who’ve been impacted by war, bringing with them experiences the like of which no child should have to endure. Some have had direct experience of the bombing raids, losing people, pets, homes and possessions that way; others have relatives and friends in the worst-affected regions of Ukraine and know about the impacts of the war through the experiences of those people; many continue to live apart from their male relatives who have stayed behind and are involved in the fighting, leading for some to further loss of loved ones as the war drags on. In short, it is not difficult to understand that some of our Ukrainian children may have a need for extra support as they learn to live with grief, separation and losses big and small - these experiences on top of the stress of getting used to living in a new country and a new language. Hence the creation of the B-ELSA role, one way in which Hampshire has responded to the support needs of children from Ukraine.

The B-ELSA role

EMTAS Ukrainian and Russian-speaking Bilingual Assistants have been ELSA-trained by Hampshire Educational Psychology (HEP) and they continue to receive the same supervision from HEP as school-based ELSAs. They are deployed to partner up with school ELSAs to plan and deliver ELSA sessions to children from Ukraine. Because of this collaborative approach, the child can access their ELSA sessions using any or all of their languages. While the B-ELSA moves from school to school throughout the working week, the school ELSA stays put. This ensures that the child has someone they can go to who understands their situation and is there for them all the time; they don’t have to wait for the next B-ELSA visit to get support. What the B-ELSA brings to the sessions is two-fold, both language and culture. Thus the B-ELSA can be a link with home for the child, bridging gaps between home and school in ways in which their school-based colleague cannot.

The school

Fairview School in south-west Hampshire is a one form entry primary school with around 240 children on roll. Most of the children are English-speaking and numbers of learners for whom English is an Additional Language are low at around 5%. The arrival of children from Ukraine has been a learning curve for everyone at Fairview, but people have been open to taking on this challenge and responding in ways that nurture a sense of belonging; the Ukrainian children are seen as bona fide members of this school’s community.

Meet Yehor

After the initial shock of joining the school in Year R, his first experience of being in an all-English environment, Yehor seems to settle in well. He tells me he is the youngest of three children and he talks about his dad, Stefan, and an uncle and aunt; these are the people in his family unit. Yehor likes Minecraft and stories. He plays football and he is partial to a custard cream. He doesn’t seem like a child who’s heard bombs falling on his home city, Kiev, or sat for hours in bomb shelters, waiting for the all-clear.

Yehor’s mother died when he was a baby so Stefan is parenting on his own alongside holding down a full-time job. The older siblings help out, collecting Yehor from school. Yehor says they sometimes call him the baby of the family; he doesn’t much like this.

Stefan is keen that his children maintain their language and culture and so when Yehor gets home, there is Ukrainian school work to be done too. Yehor is proud to be Ukrainian and keen to do well. He says

“If I do everything neatly, my dad will take photograph and send it to my teacher in Ukraine. My Ukrainian teacher says I am the best boy who write in Ukrainian.”

At Fairview, all is well until Year 2. By this time, Yehor is 7 and he’s been here two years. His English is developing well and he is able to access the learning, and is especially keen on maths. However, he begins to demonstrate some behaviours that tell staff he needs a different kind of support. When things don’t go his way, Yehor throws or breaks things, bangs his head on the table or retreats under it. If another child has something he wants, Yehor snatches it. If they get in his way, he roughly pushes them aside.

It is the school’s Head and Deputy who first suggest trying B-ELSA support, having heard about it at a district Head Teachers’ meeting. The school SENDCo agrees; she understands that these new behaviours might be Yehor’s attempt to communicate that he is struggling to navigate the bumpy terrain of living two very different lives, each with its own set of demands and expectations. One he lives at school in English and the other at home in Ukrainian – two different languages, two different cultures; small wonder he’s experiencing difficulties finding his way aged just 7 and with no route map to help him.

The B-ELSA-supported sessions

EMTAS B-ELSA Olha is the person in this story whose job it is to help Yehor build his own bridge so that he can navigate life in two languages and manage the emotional side of that experience. In her B-ELSA role, Olha says she sees herself as a facilitator, letting the school-based ELSA lead the sessions, ready to step in if a child seems hesitant, or if she sees there’s been a misunderstanding. School-based ELSA Hannah’s job is to provide continuity and to be the person who is there for Yehor every day, noticing when he’s coped well with a tricky situation and offering him an encouraging word, and feeding her day-to-day observations of him into session planning.

The two aims of Yehor’s B-ELSA-supported sessions are 1) to work on Yehor’s social skills and 2) to help him understand and name his own emotions – a vital step towards managing them for himself in more positive ways. In line with best practice for this way of working, at the start of each of Olha’s visits, and before Yehor joins them, Hannah briefs Olha on what’s been going on for Yehor between times. At the end, when Yehor’s gone back to class, they spend another few minutes reflecting on how the session went and planning for the next one.

After the second series of sessions in the autumn term of Yehor’s Year 3, the situation is much improved. Yehor is able to use lots of new words to talk about emotions – his own and those of others. He can identify when he is feeling angry and he describes ‘hot chocolate breathing’ as a strategy he’s learned in his B-ELSA-supported sessions and uses to calm himself down.

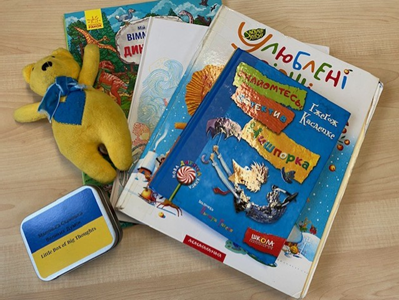

Yehor says the best part of his B-ELSA supported sessions has been the stories; he’s loved having Olha read to him in Ukrainian at the end. This has for Yehor been an affirmation of his Ukrainian identify, a link with his home language and his home country. It’s also been an opportunity for him to explore a new role, that of interpreter; he tells Hannah in English what the story’s about as they go, and he’s become really good at it, both Hannah and Olha affirm. Thus his sense of his own identity has been boosted and he has learned to accept praise where he’s achieved success, here as a young interpreter.

When asked if he’d recommend B-ELSA-supported sessions to other children from Ukraine, Yehor says “definitely,” adding that the sessions “…helped me a lot…to talk about how I’m feeling.” Now, when asked about school in England, Yehor tells me, “whole entire class is my friends.” He goes on, “I have to do everything correctly, listen, be good, be kind,” and he knows some ways to show those behaviours now, thanks to the sessions he’s had. And so we leave Yehor, a happy, settled, talkative boy who is now able to more fully enjoy the experience of growing up in more than one language.

___________________________________________________

For more information about children here as refugees, for

free resources and for specific information about accessing B-ELSA support for

a child from Ukraine, see the EMTAS Moodle Course: Asylum

Seeker & Refugee Support.

By Olha, EMTAS Bilingual ELSA and Sarah, ELSA at Shamblehurst Primary School

The Little Box of Big Thoughts from ‘Bear Us in Mind’

This blog explores how Bilingual ELSA (B-ELSA) support has worked at Shamblehurst Primary school in Hampshire. It brings together the perspectives of highly-experienced school-based ELSA Sarah, and EMTAS B-ELSA Olha. They collaborated to provide ELSA support to children from Ukraine. After an introductory section outlining why children from Ukraine might need ELSA support, the blog continues in the style of an interview, with questions followed by responses from these two practitioners.

Why B-ELSA support is particularly important for children from Ukraine

The need for this sort of support arises because of the array of challenging experiences many Ukrainian children will have had, related to their displacement from country of origin. For each Ukrainian child who has come to the UK as a refugee from war, their journey will be unique and may include things such as:

- sudden departure from Ukraine when the war started

- loss of their home in Ukraine

- loss of belongings

- separation from family members, who remain in Ukraine

- separation from friends

- leaving their pets behind

- not knowing for how long they will be in the UK

- adapting to living in someone else’s house with their rules and expectations (if with a host family in the UK)

- needing to adapt to life in a new language and culture

- loss of voice

- loss of choice

- loss of power and control over key aspects of their daily lives.

The

above examples all contribute to toxic stress, and come on top of other, more

common situational challenges that any child may experience, such as divorce or

changes in their family’s financial circumstances. Toxic stress can manifest itself in

physiological symptoms such as tummy aches or headaches, and in behaviours such

as withdrawal, regression to an earlier developmental stage or exerting control

through what appear to be acts of defiance or refusal, this strongly linked to the

child having lost their sense of self actualisation.

The EMTAS B-ELSA role was developed as a way of offering support with their emotional literacy to children from Ukraine, many of whom have an attendant language barrier to contend with on top of all the other worries and stresses they carry round with them daily. B-ELSAs work collaboratively with school-based ELSAs to plan, deliver and review ELSA sessions with children from Ukraine. The remainder of this blog draws on the experiences of Olha and Sarah who have successfully worked together to plan and deliver ELSA sessions to children from Ukraine.

How did you identify that your Ukrainian children needed ELSA support?

Sarah: Well, we noticed that there were things happening for the children at school that caused us to become concerned about them. Teachers were key in identifying that there may be a need in addition to learning English. This was discussed with our SENDCo and people on our Senior Leadership Team. Our Head Teacher played a role too and has been very supportive of the collaborative way of working that comes with B-ELSA involvement.

What have been the challenges in getting B-ELSA support to work?

Olha: In general, whilst I have dedicated slots in my calendar for this work, some schools have said they can’t release their ELSA to work with me, so that’s been a problem. Another issue I’ve had has been matching up calendars – mine and the school ELSA’s - to achieve consistency with the days and times of my visits. In this school, it’s been easy because the Head Teacher has been so supportive.

Sarah: To be perfectly honest, before I worked with Olha I did think in schools we are so busy so if she’s coming, it’s two adults to one child. I didn’t get it to start with - I thought ‘why don’t you just do the session on your own?’ But I totally get it now.

Olha: Yes, same here - on a personal level, when I first started B-ELSA work, I wasn’t convinced I needed to be there at all as some children from Ukraine didn’t seem to need me for the language support. I’ve changed my mind about that having had the experience of working with people like Sarah, and seeing how beneficial it is for the children.

Sarah: I think it was crucial you were here. You can give the children a real connection to home, because you give them opportunities to speak in first language. Each week, the children have looked to you for support to express particular things they’ve wanted to say; they’ve really benefited from that. Also the collaborative approach means when you stop coming, the child still has someone they know and can trust in school, someone who understands and is there for them.

How have you gone about collaboratively planning and delivering ELSA sessions?

Sarah: I’ve been really fortunate in that my school has been so open to B-ELSA support. I’ve been given two hours a week for our two Ukrainian children, which is an absolute gift; in my regular ELSA work I don’t usually get the luxury of planning time. Working with Olha, whilst I have suggested some possible activities for sessions, I’ve also valued her opinion and input. With the extra time, we’ve been able to plan sessions together, and we’ve shared our ideas.

Olha: Yes, so 15 mins ahead of the session with the child, we’ve met to recap on the previous session, and share and consider feedback from teachers about what happened for the child during the rest of the week between visits. It’s helped us tailor the sessions so we get them right for each child.

How have you figured out appropriate targets for the children you've worked with?

Sarah: One child had some friendship issues so we’ve done some work on that. They joined Year 5 and had to negotiate their place amongst friendships that were long-established within the peer group. For them, it’s been the social aspects that have been more immediately challenging, yet vital as they need to build a new support network for themselves and to gain a sense of belonging here in school.

Olha: Yes, and it’s been really helpful that Sarah knows the other children in the class. She’s brought that knowledge to the sessions – I wouldn’t have been able to do that bit on my own. For this child, we’ve also worked on boundaries, the need to respect others’ feelings, what we can do for ourselves when we’re feeling upset. So lots of work on emotional literacy.

Sarah: For another child, we decided we’d work on social skills as they’d been having difficulties following instructions in class. We introduced a second child and we played some games together. We talked about the rules of those games. The Ukrainian child said they wanted to make a booklet so we came up with the idea of making a book of rules – things we need to remember when we’re playing with friends. Each week we played a different game and we talked about the rules.

Olha: Yes, they knew we were working on that book, which was their idea. At the end, they were so proud of their book of rules and they took it to share with their class. I believe this child was more focused and engaged because we followed that project with them, their own idea.

How did you draw on the child's first language in your sessions?

Olha: I’ve collected resources in Ukrainian, Russian and English through this role. Some have come from my ELSA training with the Educational Psychology service; I especially like the ones from ‘Bear us in Mind’ – which is a charity set up to support refugee children, including those from Ukraine.

Sarah: We wanted to make sure the children understood the feelings words we were using. We used cards to talk about that. The children definitely needed Olha to be able to do this effectively. Also, after seeing some of the resources in Ukrainian that Olha brought with her, I started using translation tools myself, to create more.

For me, the language options Olha’s opened up for the children is the beauty of it – we’ll come in and have a chat about each child and go in my ELSA cupboard and choose something suitable. For example the feelings cards – we picked a few cards and we asked what’s happening in the picture. If we could add a speech bubble to the picture, what would they be saying/thinking? Because Olha’s been there, the children have been able to use whichever language they like to express their thoughts and ideas. I think this has been a real strength of it.

What has been the hardest part of working in this way?

Sarah: To be honest, at the beginning I was concerned about my waiting list children. I have lots of children with lots of needs. Prioritising the Ukrainian children did make me feel a bit bad. But a child at the top of my list was the one we chose to join some of the B-ELSA-supported sessions, which was great, really fortunate that it worked out that way.

Also, the targets from the teachers needed a bit of work to get them right for the children.

Olha: We agreed on that – it’s been really common in my experience in this role. Teachers sometimes think we have a magic wand and can solve anything and everything, but ELSA support can really only help with one thing at a time.

Sarah: Yes, when we had our Remembrance Day, one child suddenly started talking about everything they’d been through and the teachers and the other children were shocked to hear it. I think when something like that happens, people can go into panic mode.

Olha: I think this is sometimes where it doesn’t work so well in other schools – people lose confidence. They sit back and they seem to want me to do everything, which isn’t how it’s meant to work.

What's been the most useful thing to have come out of your collaboration?

Sarah: The legacy – through the work we’ve done together, the children have accessed the ELSA sessions so they’ve benefited from that. Plus now they know me really well, and they understand I’m always here for them, even if Olha’s visits have ended for the time being.

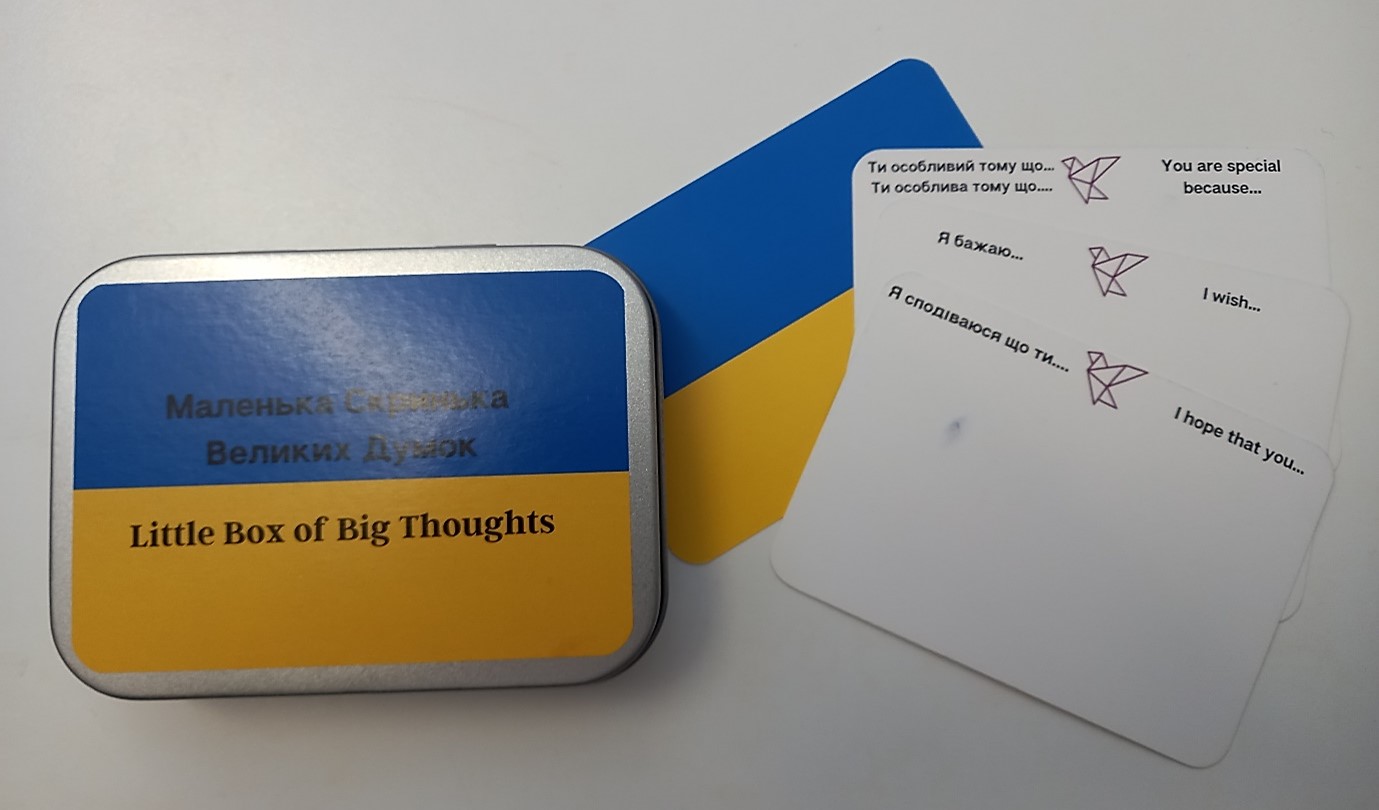

How do you achieve a sense of closure at the end of a period of ELSA support?

Sarah: Closure was really important for the children. In the end, we decided we’d give each child a card, so I modified one I had. In it, we put that Olha’s saying goodbye but the child can still come and talk to me.

Olha: Yes, a card like

this is a resource we’re now developing at EMTAS. The new cards will be printed with space to

add something personal, special to each child. All the EMTAS B-ELSAs will be able to give

them to the children they’ve worked with.

The

above conversation outlines some of the challenges associated with accessing

B-ELSA support for children from Ukraine and some of the benefits – for the

children, for their peers and for the adults around them. It illustrates how one school has added B-ELSA

support to their work with Ukrainian children and their families, developing a

healing environment in which the children can begin to recover from the trauma

they’ve experienced. To find out more

about working with refugee children and to access various free resources,

including ‘Bear us in Mind’, mentioned by Olha, see Course: Asylum

Seeker & Refugee Support (hants.gov.uk).

by Smita Neupane and Sudhir Lama, Nepali Bilingual Assistants with Hampshire Ethnic Minority and Traveller Achievement Service

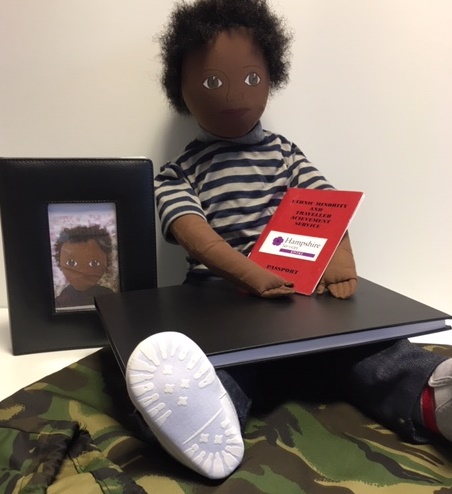

Have you ever used a Persona doll? Do you know how and why to use a Persona Doll? Persona Dolls are an ELSA resource and emotional literacy support tool used to initiate talk and to share experiences within the classroom. EMTAS were awarded an amount of money in an MOD bid to work with Infant and Early Years settings to introduce Personal Dolls to help all children cope with the demands of moving school, house, and even country with a particular focus on Service children. The Persona Doll project is also designed to involve the family and community and to share experiences with peers. It has an intergenerational element with the involvement of secondary pupils supporting the creation of some of the resources.

In the beginning…

Hampshire is an area rich with Service children across the length and breadth of the county and spanning all the educational phases. The project is designed to support Early Years children but to make it relevant, the experiences of older children was needed and had to be included in the package.

Initially, before the Persona Dolls had joined us, the work started at The Wavell School, with two Nepali Bilingual Assistants from Hampshire Ethnic Minority and Traveller Achievement Service (EMTAS) interviewing students with backgrounds from Fiji, Nepal, Malawi and Jamaica. They shared their stories and were open and honest about their experiences including the difficulties faced during transition and the worries about having a parent in the forces. They spoke of homesickness and missing friends and family, the foods they missed and aspects of their lives that had changed. Some of the students were UK born so had not lived in their parents’ country of origin so they took time to find out as much about their culture and history as they could through their families and community. The students created talking books from this information that included pictures and speech both in English and first language. Some of the books included nursery rhymes from their culture and how to count in their first language. The books are proactive and help bring the Persona Dolls alive. The Wavell children chose the dolls and named them ready for their journey into their schools.

First steps…

When the Talking books were all prepared and each Persona Doll had its name and a passport produced, they were packed up ready to travel with their big note book to record their experiences. The dolls have been taken to infant and primary schools all over the county and the idea is that they stay in that school for roughly half a term and then they are off on their travels again. The doll is taken into the school and introduced into the class where it will be staying and the children get to ask it questions and to find out what it likes and dislikes.

Some ground rules were set:

- doesn’t matter how dirty the doll gets

- no face painting, hands or feet painting of the doll!

- it is not to be used as a reward

- it has to be included on the register

- it has to have its own seat, peg etc.

- it has to have lots of different experiences

- everything has to be recorded in the Persona Doll’s book and shared.

The first doll to leave EMTAS was Himal, a Nepali boy, and he went off to Talavera Infant school and Becky the class teacher. Becky and the class totally embraced this project and the work was amazing. Himal attended an Eid festival where he was gifted new shoes. He went to a Christening. He went to a hot tub party (but just watched). He also shared his feelings about moving to a new school and how this made him feel.

The Persona Dolls generate lots of discussion with the children. It encourages them to think about how they feel when they experience trying something for the first time. It makes them think about what a good friend is and how a good friend can support a new arrival. It allows the children to talk about things that may worry them about transition and about what is happening in their lives at home and at school.

Desired outcomes …

It is hoped that the eight dolls will continue to transition from setting to setting and may even revisit schools they have been to already as can happen with Service children.

One of the aims of the project was to help build up pupil self esteem and confidence. It is hoped that through exposure to the stories children will want to talk and share their own feelings and experiences. Through listening to each other’s experiences it helps children realise that they are not alone in what they are feeling and it is okay to feel that way.

While the project has a fun element of taking the doll to different celebrations and events it is also teaching social and emotional skills through communication and responsibility.

The feedback so far from two schools has been very positive and the children have loved having their guest to stay and were really sad when they left. This too helped teach pupils resilience as many children feel unhappy and lost when their best friend moves on and this helps them build up coping strategies to deal with this and invites discussion within the classroom to look at feelings.

Do you want to be part of this?

If you are a Hampshire school and would like to be part of this ongoing project please email Claire Barker, claire.barker@hants.gov.uk. We would be delighted to have you come on board and training is available this term.

Please see our website for further information on the use of Persona Dolls.

If you are a school outside Hampshire and would like a chat about how to set this up in your area, please contact Claire Barker, claire.barker@hants.gov.uk.