Site blog

By Astrid Dinneen

In a previous blog, Hampshire EMTAS Team Leader Sarah Coles and Specialist Teacher Advisor Astrid Dinneen considered ways of supporting Hatice, a Turkish-speaking pupil in Primary school working within Band A of the Bell Foundation EAL assessment framework. In this blog, we catch up with Hatice and explore EAL practice which may support her as she continues her journey towards full academic proficiency.

It’s been nearly a year since we last wrote about Hatice, a new-to-English pupil literate in Turkish who joined Year 5 in her first UK school. Avid readers of our blog will remember that her teacher chose to put in place EAL-friendly strategies to help her access the curriculum alongside her peers. For example, a home-school journal was embedded so Hatice could discover, research and translate vocabulary in advance of lessons. In addition, grouping was considered to ensure she was exposed to sophisticated speakers of English as part of a trio. Finally, another powerful way to help Hatice engage with her learning in class was to build in opportunities for her to use her first language. She used translation apps downloaded on the class iPad and wrote in Turkish to annotate handouts as well as to demonstrate her learning. This resulted in Hatice feeling included and motivated to take part in a broad and balanced curriculum.

Fast forward to now, Hatice is in Year 6. She’s working securely within Band B and she is starting to demonstrate features of Band C, particularly with listening and speaking. Hatice is a popular member of the class. She has many friends and appears very chatty on the playground. She has formed good relationships with a range of adults in the school with whom she also enjoys conversations about her activities and the things she enjoys doing at home and at school. Hatice listens carefully in class and regularly takes part during lessons to contribute to whole class discussions and collaborative group activities. Her home-school journal is still in place hence she continues to be familiar with vocabulary linked to her subjects. She also has a good go at using her keywords in her contributions. Hatice feels more confident about her speaking in English hence she is increasingly attempting to write in English. However her teacher has noticed that whilst pre-rehearsing vocabulary in advance has helped Hatice become familiar with language at single word level, she appears to need further support at sentence and whole text level.

So what now? How can her teacher build on Hatice’s success? What does EAL practice look like for learners who are beyond the early stages of learning English?

It takes a long time for pupils to acquire both informal and more academic language – anything between 5 and 10 years. To make further progress pupils will continue to need support along the way through amazing teaching and learning. In fact Hatice’s teacher should feel reassured in the knowledge that keeping going with EAL-friendly strategies rather than a decontextualised English-first approach is recommended, even after the first few months. This means persevering with practice already in place for Hatice eg inclusion in the language-rich classroom, discovering vocabulary in advance, grouping with good language role-models and using first language as a tool for learning is still recommended.

With the latter in particular, pupils embarking on Band C will still benefit from reading texts in their first language. Technology to support this continues to evolve – colleagues are now encouraging the use of Google Lens and Immersive Reader which both allow pupils to read and listen to translations instantaneously. And whilst pupils like Hatice may increasingly produce their writing in English, it is important for opportunities for first language use to still be part and parcel of teachers’ planning. For example, Hatice may be planning her writing in Turkish and later completing it in English. Encouraging the use of first language at the planning phase reduces the cognitive load, helping pupils keep momentum for the writing phase. Likewise, routinely using translation tools will undoubtedly also continue to support pupils on their journey to full academic proficiency.

New-to-English pupils tend to make rapid progress initially, particularly from Band A through to Band B. This may give us the illusion that they require little EAL support after this point. However, after this initial stage it isn’t uncommon for pupils to reach a plateau as they embark on Band C ie ‘Developing Competence’. This is usually because ‘pupils with advanced fluency in spoken English are often left without support because their conversational competence masks possible limited vocabulary for curriculum purposes’ (Cummins, 1999).

So what else can Hatice’s teacher put in place to help her choose the best ways to express herself?

Let’s explore whole class strategies that will not only benefit Hatice but also her peers, whether they are EAL or not. Her teacher may like to build on the pre-reading of keywords happening at home and plan in whole class word level activities such as bingo games, word races, dominos etc. For example, imagine that a final outcome for a whole-class topic was for pupils to write a balanced argument on whether climate change is natural or man-made. Hatice may have talked about climate change in Turkish at home and translated tier 1 and tier 2 keywords such as hemisphere, scientists, sea levels, etc. in advance. Back in class, the whole class could also focus their attention on this language. A word race for example would see pupils work in pairs or trios to find definitions hidden around their classroom and match them to the keywords. Alternatively, a bingo game would see Hatice’s teacher read out the definitions for pupils to cross off their card (bingo card generator apps can help resource this).

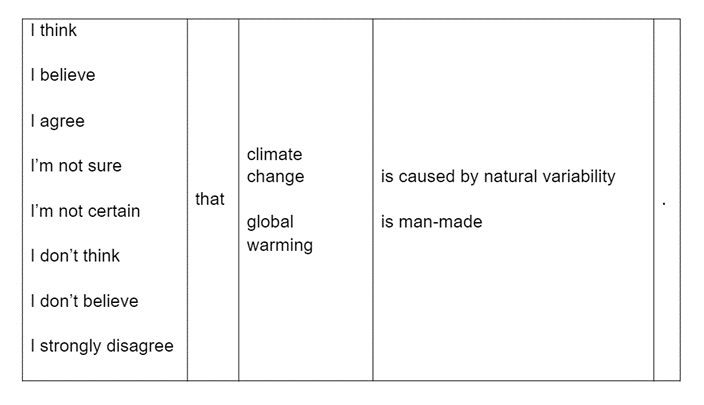

Having focussed pupils’ attention on subject specific language at word level, Hatice’s teacher could support language at sentence level. Sentence structure can be modelled and made explicit thanks to substitution tables - an extremely useful scaffolding tool to support speaking as well as writing. A substitution table is a simple frame which allows the learner to follow the correct syntax in a sentence whilst retaining autonomy over the choice of words. To continue with our theme of climate change, a substitution table could help Hatice (and others in her class) to express her views using more formal language, aided by an interactive opinion line activity:

As for modelling whole paragraphs and longer pieces, Hatice and her class could be provided opportunities for listening and speaking to prepare themselves for writing. Dictogloss lends itself well to this as a What A Good One Looks Like (WAGOLL) activity. In Dictogloss, pupils listen to a pre-prepared model text and take notes. Then they use the language they’ve heard to work with their peers (first orally then in writing) to recreate a similar piece. The end product is typically a piece of writing which includes some of the language and structures used in the model, but is not an exact replica. Dictogloss is an opportunity for pupils to hear a model that includes all the subject specific vocabulary, ideas and other things covered in class, and then to collaborate on using these same components to produce a cohesive piece of writing in keeping with the target genre.

To see what Dictogloss might look like in practice, readers can join one of our online network meetings. We will discuss the steps for Dictogloss and give a demonstration linked to our theme of climate change on January 10th and March 27th. If you cannot wait that long, why not talk to your EMTAS Teacher Advisor about whole staff training? You can also liaise with the English HIAS team to find out how EAL strategies can be woven through the English Learning Journey. For further resources, check our Guidance Library on Moodle and visit the HIAS team’s own platform.

Hatice is pronounced /hætidʒe/

By Hampshire EMTAS Team Leader Sarah Coles and Astrid Dinneen, EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor for schools in Basingstoke & Deane

With the increase in numbers of children joining our schools from overseas with very little English, practitioners in schools are asking how best to proceed. Should they first focus on teaching the children English or is there another approach?

EAL best practice tells us that the best thing to do for such children is to include them in the full mainstream curriculum being delivered in schools via the medium of English. This can be scaffolded in various ways. The children should not be withdrawn to be taught English separately or as a prerequisite to being allowed to join their peers in regular lessons. But this immersion approach can seem an alarming response; surely the children will not be able to understand anything and will flounder and fail, people may think. So instead some opt for an ‘English first’ approach. They buy in an online English teaching app or print off worksheets for the children to learn the days of the week and the colours in English whilst their peers are learning about how plants grow or the story of The Titanic or Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

The problem with the English first approach is that far from helping, it actually slows down the children’s progress in their acquisition of English, as well as making it harder for them to feel welcomed and included in the life of their new school. Plus it adds to teachers’ workloads; now they are having to source materials for an entirely separate curriculum as well as plan for the rest of their class.

To illustrate this in more detail, consider these two

approaches for the same newly arrived child whom we shall call Hatice*. Assume Hatice

is new to English (Bell Foundation EAL Assessment Framework Band A, to those in

the know) and literate in Turkish.

Scenario 1: English first

The teacher decides to plan separate provision for Hatice, because they feel their mainstream English lesson is too challenging for Hatice’s level of English. So whilst the other children are preparing to write a letter persuading their Head Teacher to shift the start of the school day back by an hour so they start at 10.00 instead of at 9.00, Hatice will sit on her own and work through some sheets that focus on learning the English words for some colours and common classroom objects. In one example below Hatice is required to draw and colour the correct classroom object in the empty box.

It is a…

|

red |

pen.

|

|

purple |

book.

|

|

|

orange |

chair.

|

|

Fortunately, Hatice is compliant, meaning the teacher can get on with teaching the rest of the class. Hatice spends the whole morning working on these worksheets on her own. She doesn’t disrupt anyone but the teacher notices that she regularly has her head down on the desk and appears to be dozing.

At the end of a couple of weeks at school, Hatice is still very much on the periphery of things in the classroom and needs frequent reminding when she is included in instructions given by the teacher, for example when it’s time to get ready for PE or line up to go to assembly. She spends long periods of time gazing out of the window and generally seems to lack motivation and enthusiasm for anything other than home time.

There has also been a deterioration in her output and she

now very rarely completes the worksheets she is given. Where she has had a go with

tasks that require writing, her handwriting is much less tidy and it seems she is

taking increasingly less care over her work.

With regards to friendships, it seems to be still very early days and Hatice has not formed any strong relationships with her peers. She continues to spend most of her time at break and lunch times on her own.

Her teacher reflects on practice and provision so far. It has

taken a lot of time planning, resourcing and marking the worksheets for Hatice,

yet she does not seem to be making progress. He is not sure what else to do but

feels this is not a sustainable approach in the long term. He is interested in

finding out about alternatives…

Scenario 2: immersion using EAL-friendly strategies

Hatice’s teacher plans to include her in the lesson along with everyone else from the get-go. First off, before the series of lessons begins, the teacher sends Hatice home with a list of words in English to be translated into Turkish with the help of parents. He asks them to talk to Hatice about the concept of ‘persuasion’; what does the word itself mean and in what in real life scenarios might we use persuasion to get the outcome we desire? The teacher recommends the family use a translation tool like Google Translate to help them to do this:

English word/phrase |

Turkish (Türkçe) |

Persuade (someone to do something) |

ikna etmek |

We think |

düşünürüz |

Benefit |

|

Consider |

|

Because |

|

Late/later |

|

Traffic |

|

Drawback |

|

Ensure |

|

Potential |

|

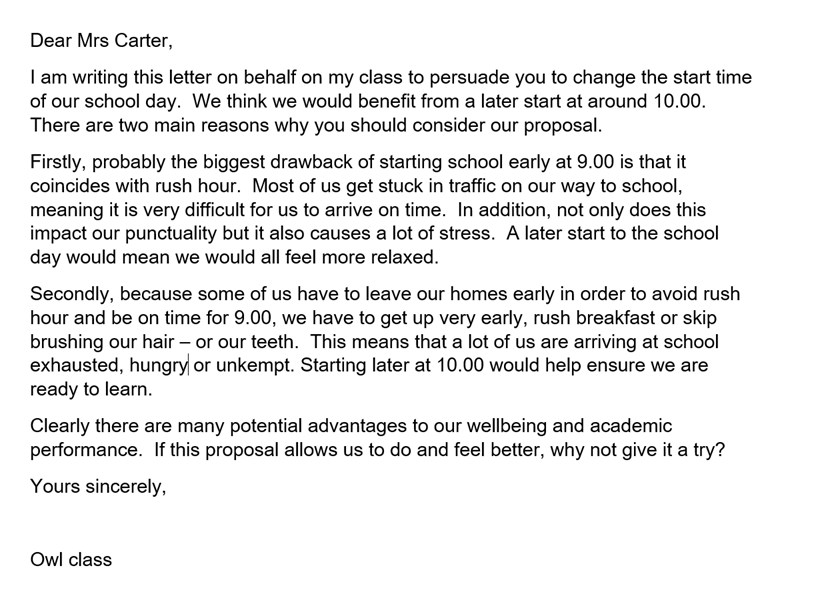

The words the teacher chooses for this are drawn from a model letter which will be used in the lesson the following day. The teacher chooses to write the model himself to incorporate the language of persuasion, different persuasive techniques and ideas already suggested by the children themselves. At other times, he might have used ChatGPT to generate a model in no time.

Having diligently completed her pre-learning at home with

the help of her parents and discussed the concept of persuasion in Turkish, Hatice

is very proud to bring in a dual-language glossary she has started in her

special book. She places it on her desk

next to her pencil case. Her new buddies seem to be taking an interest in the

stickers she has stuck on her book and this adds to her feeling of pride.

She is also pleased to recognise the vocabulary she has researched and translated in a handout placed on her desk by her teacher. Everybody else is given the same handout. Hatice is intrigued and delighted to see she might not be doing different work today. Plus a Teaching Assistant approaches her holding a tablet and shows her how to scan the text to translate it into Turkish. Hatice smiles and chuckles as she reads the translation and discovers the text is a letter asking their head teacher to delay the start of the school day.

Highlighters are distributed and her buddies start a conversation. They’re highlighting parts of the letter. Hatice checks the tablet to see the translation again and tries to match the highlighted text to the translation. She starts to neatly annotate her letter in Turkish. Her teacher looks happy so she continues her annotations and adds to her dual-language glossary words such as ‘firstly’, probably’, ‘clearly’ etc. Her buddies highlighted them so Hatice thinks they must be important.

Later on, the children are to write their own letter using

features of the original. Hatice’s teacher suggests to her that she could write

her letter in Turkish. Hatice happily engages with this, writing fluently and

at length, sometimes self-correcting and adding punctuation. She writes in

paragraphs and her sentence starters seem to vary. She even attempts to

incorporate some English vocabulary eg ‘firstly’ and ‘clearly’. This reassures Hatice’s

teacher who can see she has lots of ideas and things to say. He notices Hatice

sometimes looks at her peers’ writing - both are quite happy to show her their

work – and is making use of the tablet to communicate with them using translation

apps.

What now?

Experimenting with EAL pedagogy has proved promising as it’s meant Hatice has felt included, motivated and able to meet curriculum objectives in a differentiated way. Her teacher would like to build on this by trying other EAL strategies such as substitution tables and Dictogloss, planning further opportunities for listening and speaking and continuing the use of Turkish as a tool for learning. To explore these further why not join one of our online network meetings?

EMTAS

training courses | Hampshire County Council (hants.gov.uk)

*This child's name is pronounced /hætidʒe/

Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Chris Pim busts popular EAL myths

Anyone who works with EAL learners, particularly those at an early stage of learning English, knows how challenging this can be. The only common factor besides varied exposure to English is that these pupils have another influencing language in their background. In all other respects they vary as much from each other as non EAL pupils. Not only do we, as practitioners, need to consider the overall aptitude of a learner but also complex issues such as proficiency in first language, cultural factors, previous learning experiences and family circumstances. This makes effective support for EAL learners particularly difficult and raises some important questions. How do we know whether our current provision is working? How do we know that an alternative intervention or set of support strategies might not produce more effective results?

As a specialist teacher adviser, working for an established ethnic minority achievement team, I have come to an understanding about what I believe works best with EAL learners at different stages of acquiring English. My assumptions have been informed by looking at findings from more than 40 years of research, as well as observation and personal experience over many years working in this sector. Yet sometimes there would appear to be a mismatch between what happens on a practical level in schools and my understanding of best practice. So why would this be the case?

On one level it is my belief that effective provision for EAL learners can, at times, seem counter- intuitive. Take the issue of whether new arrivals should have acquired a basic level of English before entering mainstream provision. This is still a perpetuating myth, as it seems pretty clear that pupils would have a better chance of engaging with the curriculum if they had a good grasp of colloquial English, than if they didn’t. Whilst at face value that is undoubtedly true, the alternatives on offer in terms of offering a bespoke curriculum outside of the mainstream do most pupils no favours, either in terms of accelerating their development of academic English or enabling them to acquire curriculum-specific skills and knowledge. In addition, it has been shown to knock self- esteem and is a very expensive form of intervention. Except in rare circumstances most pupils simply do not need this level of intervention so long as they are being taught well in the mainstream.

It may be that an English first approach persists as an idea and a practice because it makes us as practitioners feel more comfortable; we project our feelings of inadequacy as we see new to English learners struggling with the undoubtedly challenging demands of learning new knowledge in an unfamiliar language. It is the same fear as restricting pupils’ use of their own first language as a tool for learning. We don’t understand what children might be saying, don’t know what bilingual sources to use and can’t mark their work if they write in an unfamiliar language. Therefore, some believe these types of approaches are to be avoided, despite unequivocal evidence that this benefits most learners who are orally fluent and literate in one or more other languages.

One widely held belief goes like this: Our early stage learners of English would do better if we reduce the cognitive challenge in the work, perhaps grouping them with ‘less able’ pupils where there is often an additional adult available to offer support to the whole group. In some cases, this belief extends to withdrawing pupils for an intervention session, either 1:1 with an adult or in a small group guided session. To be clear, grouping EAL learners with less able pupils and significant amounts of withdrawal intervention are not effective approaches for all sorts of reasons. Guided sessions also tend to limit the quality of peer-to-peer dialogue which is generally unhelpful for very early stage learners of EAL.

What I find interesting is that pupils often say they like this approach, possibly because they are receiving more attention from an adult than normal and therefore feel they must be learning something. But is it enough to implement a strategy simply because children enjoy it? Withdrawal intervention for early stage EAL learners is also popular with some practitioners who believe that their pupils make good progress in this setting. Yet it is my belief that this is a pedagogical placebo. By this I mean that any reasonable intervention from an adult is likely to help a pupil make progress. But will this be more successful than what the pupil would have received if they had remained in a well-taught mainstream lesson with the class teacher?

My advice is to keep early beginner EAL learners in the classroom as much as possible. Provide these pupils with the same curriculum and experiences as their peers, support access with sound EAL pedagogy and offer them alternative ways of demonstrating their learning.

Explore the following links for guidance around good practice teaching and learning for early stage learners of EAL:

- Bell Foundation EAL Assessment Framework

One question often asked is ‘What are the differences between teaching English as an Additional Language (EAL) and teaching English as a Foreign Language (EFL)? They’re practically the same thing, aren’t they?’ Lynne Chinnery, Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor on the Isle of Wight clarifies how these approaches to English language learning are distinctively different from each other.

Who are EFL and EAL learners?

English as a Foreign Language (EFL) is used to refer to both adults and children learning English in a non-English speaking country or in the UK for a limited period of time, such as a summer course. English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) mainly refers to adult learners of English in the UK attending English language classes. English as an Additional Language (EAL) is usually used to refer to children who are living and attending school in the UK and whose first language is not English.

Practitioners should remember however that ‘pupils with English as an additional language are not a homogeneous group’ (Naldic, 2012a); their age, background, previous education and previous experience of language learning will all play a part in shaping the way they learn English. Practitioners will therefore need a variety of EAL specific approaches to help each individual along his or her learning path.

What difference does it make?

One of the main differences between EAL and EFL is that because EFL is mostly taught in non-English-speaking countries, EFL students have limited exposure to English. They may have between one and five English lessons a week (the majority from my experience having only one to three lessons) and for many students, this time in the classroom will be the only time that they are immersed in English. They will usually be given English homework and, depending on their level, may even watch English TV programmes or listen to English songs outside the classroom, but on the whole, they will not have extended periods of communication in English, apart from their time inside the classroom.

EAL students, on the other hand, have a completely different experience. Not only are they immersed in English all day, five days a week, both in the classroom and in the playground, but they will also hear English outside school too. Even if they speak their first language at home or use it as a tool for learning, which we highly recommend, they will be listening to English all around them whenever they go out, and will eventually be communicating in the language outside as well as inside school.

One result of this is that EAL learners will normally acquire English much faster than learners of EFL. Even so, learning a language is a long process and EAL learners can take between 7 to 10 years to catch up with their monolingual peers. What is interesting to consider is the way in which they pick up the language. EAL students have time to listen to lots of talk, especially if they are seated with peers who can act as good language models. Being immersed in the language, they will begin to copy what they hear, experiment with it and eventually shape it for themselves. With lots of speaking opportunities in a supportive atmosphere, as well as a teacher and peers to model new language and recast it correctly, their confidence, fluency and accuracy will flourish. EFL students also need many opportunities for practice, but because their exposure to English is more limited, there will be much less time to develop the patterns and rules of language themselves in such a natural way. Because of this, they are likely to need more explicit instruction of grammar and syntax than the EAL student.

Another difference to bear in mind between EFL and EAL, is the fact that the EAL learner is usually alone or in a minority language group within the classroom, while EFL learners often share the same first language. This can make the initial stages of learning much more stressful for the EAL student. Sometimes early stage EAL learners also experience what is known as the ‘silent period’, where the learner begins to absorb the language around them but is not yet ready to speak. Although an EFL student may suffer some anxiety before their first lesson or two, this is not usually so pronounced or prolonged. Imagine how different it would feel if you were learning French in a class of English speaking peers at the same level as yourself compared with learning French in a class of French native-speakers!

EAL learners also differ from their EFL peers as, while they are learning English, they are also learning the school curriculum - in English, which means they have the difficult task of trying to learn English, access the curriculum and catch up with their peers – all at the same time! For this reason, focussing on vocabulary lists that have little or no connection with the curriculum, such as colours, pets or vegetables, is not good practice.

Are there any similarities?

While we are considering the differences between EAL and EFL learners, it is also important to remember that there are many similarities between the two disciplines and that what is good practice in one field can also be good practice in the other. Many methods that are recommended when working with EAL students are also used with EFL learners, such as the use of visuals, role play, paired activities and collaborative group tasks. In fact, these methods work well for all students, not just those learning EAL. In any English language classroom, the form and function of language will still need to be explored but the way language is taught has changed, even in the field of EFL. For example, endless exercises practising one particular grammatical structure, without context or the opportunity to experiment with it in natural conversation, will be of as little benefit to the EFL student as it is to the EAL student. Talk is creative: it is spontaneous and unpredictable and teachers should therefore not only plan activities which enable the student to apply the language they have learnt, but also to use it in real conversations in order for them to grow into independent learners (Naldic, 2012b).

The world of EFL has recognised this shift in methodology and most EFL course books now reflect modern approaches to language learning. We have torn out the language labs and have introduced many more opportunities for spontaneous conversation, that provide a platform to practise the structures and vocabulary taught, rather than an overreliance on drilled exercises with no avenues for real expressiveness. In this way EFL has become more in line with the pedagogy of EAL, where ‘The active use of language provides opportunities for learners to be more conscious of their language use, and to process language at a deeper level. It also brings home to both learner and teacher those aspects of language which will require additional attention’ (Naldic, 2012b).

Accessing the curriculum

EAL and EFL students will have very different experiences on their language journeys, not only because of the differing amounts of exposure to English, but also because of the purposes for which they are learning the language; EFL learners are learning English as a discrete subject whereas EAL learners are learning the curriculum through the medium of English. The good news is there are many useful strategies which work well for both EFL and EAL students, and have been proven to be good practice for all children, including native-speakers. However, practitioners working in the mainstream setting should remember that the curriculum provides the context for English language learning and therefore EAL strategies should be planned into lessons to support pupils’ access to the language demands of the curriculum. Check out Hampshire EMTAS and the Bell Foundation for more ideas.

References

Naldic (January 2012a) Pupils learning EAL [online] https://www.naldic.org.uk/eal-teaching-and-learning/outline-guidance/pupils/ (accessed 09.05.2018)

Naldic (January 2012b) The Distinctiveness of EAL Pedagogy [online] https://www.naldic.org.uk/eal-teaching-and-learning/outline-guidance/pedagogy/ (accessed 09.05.2018)

Written by Hamish Chalmers, Doctoral Researcher at Oxford Brookes University

I run the NALDIC Oxfordshire Regional Interest Group (RIG) which is a forum for teachers, researchers and others interested in the education of EAL learners. Despite the very rich and diverse linguistic characteristic of Oxford and its surrounds, the Local Authority no longer has an EAL department and therefore no longer provides peripatetic support for EAL learners and their teachers. This means that it can be very difficult for individual teachers and schools to access training that would help them to keep up to date with developments in policy and practice relating to EAL, and ensure that they follow best principles in their teaching. Our RIG meets once a term. At each meeting teachers share their expertise, we invite guest speakers to talk about research and practice and we run workshops as a component of teachers’ continuing professional development.

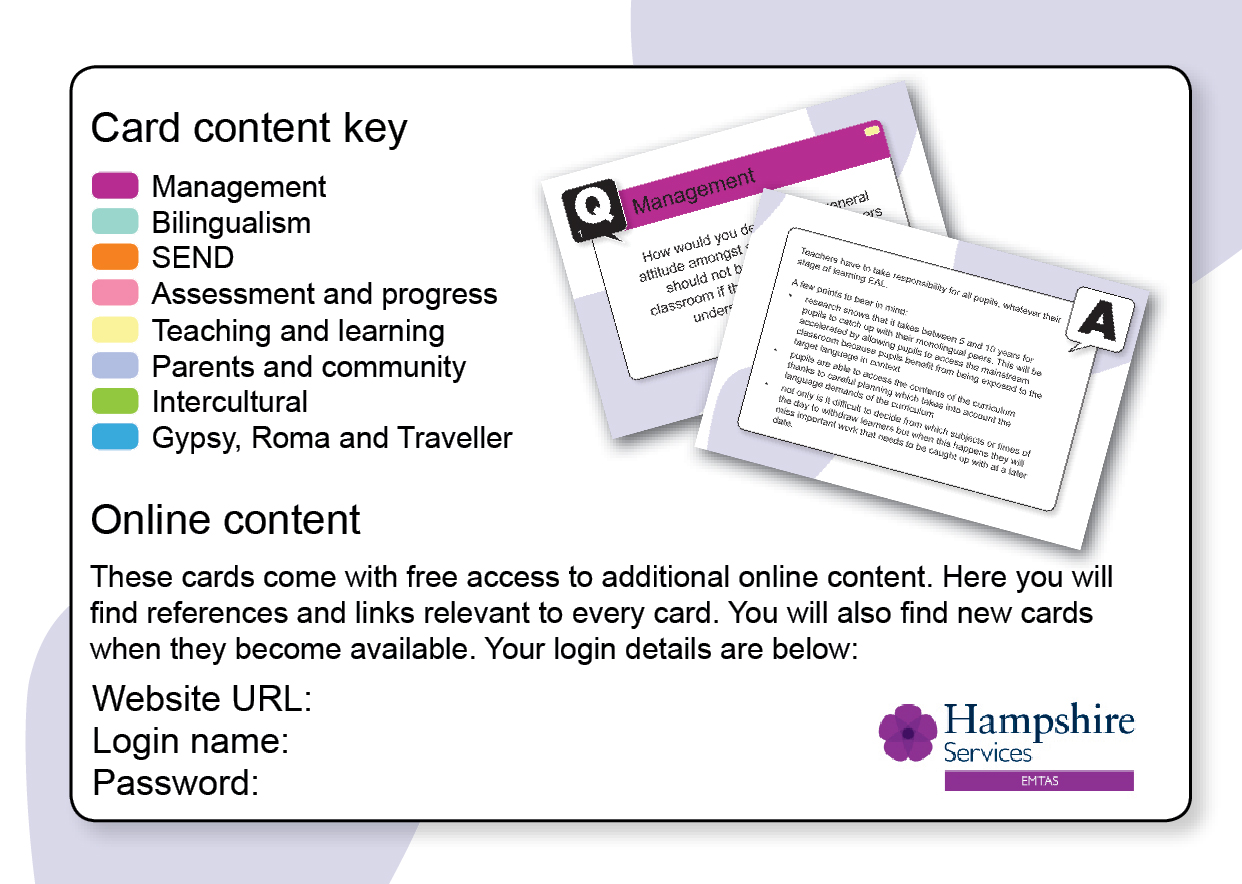

We were delighted, therefore, to be given an opportunity to try out the Hampshire EMTAS EAL Conversation Cards with the RIG this autumn. The conversation cards are an excellent way to stimulate thoughtful discussion around provision for EAL learners in our schools. Each card poses a question related to a typical scenario. For example one cards asks ‘At your school, pupils who are relatively new to English are withdrawn from language classes for extra English. What would be your opinion of this policy?’ The question is designed to prompt discussion about this authentic scenario, with a view to the discussion helping teachers to understand their own practice and policy. Each question is then answered on the reverse of the card, providing evidence-informed guidance for teachers on how best to respond. For example, the answer to the question above reiterates the right of all children to have a broad and balanced curriculum. It then explains that EAL learners are often already competent language learners, so withdrawing them for classes that build on this foundation of skills to develop English is unlikely to be in their best interests. The card then goes on to suggest things that schools should take into account when setting related policy.

The cards are organised into eight themes, each addressing a different aspect of EAL education. These include management, teaching and learning, parents and community, bilingualism, and so on. Working with a group of 30 teachers, I divided the cards into sets that included examples from each section and asked small groups to appoint a questioner who would lead the discussion with two or three colleagues. The room was abuzz with discussion and debate as colleagues engaged with the cards and considered their responses. Eavesdropping on the conversations was fascinating as it revealed a great breadth of knowledge among colleagues, but also some very typical misunderstandings which allowed for some timely myth busting by the cards.

One colleague commented on how useful the cards were for schools like hers, which do not have an appointed EAL coordinator. Here, like many schools, EAL expertise is largely down to the experience of individual teachers. In the absence of teachers who have taught in schools with large numbers of EAL learners and with good ongoing professional development, knowledge and guidance is rather hit and miss. Because the conversation cards provide evidence informed guidance for real-world scenarios, it means that anyone can lead CPD sessions regardless of their level of experience. While this might not be the ideal situation, it does mean that teachers can be confident that they are getting good advice, especially in the light of the many myths about language learning that get reinforced when expertise is lacking.

Online content

We also looked at the online version of the cards. Here, the same information is presented but can be shared using a projector, so that discussions about the same question can be held in larger groups. Our RIG members were impressed that the online version provides links to other online content that expands and reinforces the messages provided in the answers.

Using the cards in training

Colleagues left the meeting inspired to continue their learning about EAL, and sharing this with their colleagues by using the Hampshire EMTAS EAL conversation cards. Many saw the potential for including short sessions in staff meetings, dealing with a couple of cards at a time, or for one to one personal professional development meetings. We were delighted to have been able to share this essential resource with our colleagues and hope that the cards continue to shape policy and pedagogy for Oxford’s vibrant and diverse language learners.

Where to get a set of cards

You can view a sample of the cards here where you can also find the order form.

written by Sarah Coles, Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor

It is usually clear to staff in schools that there is a

support need they should address when a newly-arrived pupil from overseas

experiences a language barrier on joining their first UK school. This may be the child’s first experience of

being in an English-speaking environment, and there is much to learn in terms

of the new language. What are less

discernible – and perhaps less well-supported - are the other barriers such a

child may face – barriers that relate to differences in pedagogy, social and

cultural differences and of course the sense of dislocation and loss the

newly-arrived child may feel when they first start, having left behind all

their friends and possibly family members too.

Being placed in a situation far outside of their comfort zone, there is

a lot for a new arrival to manage in addition to the demands of having to cope

in a new language.

In the UK, pedagogical

approaches focus on children learning through experience, learning from each

other, learning through trial and error, learning through talk. From an early stage, our indigenous,

monolingual children learn how to learn in these ways and teachers, many

themselves a product of this same system, teach from an often deeply-rooted

belief that these ways are the best. We

are so immersed in the UK classroom culture that as practitioners we may forget

it’s not like this everywhere in the world.

In Poland, for example,

children do not come to sit on the carpet to learn as the carpet is perceived

to be a dirty surface that’s walked on by everyone, so a Polish child – and

possibly also their parents - may look askance when the class is directed to

come to sit there for story time.

In some countries,

children’s behaviour is managed for them,often with a stick should they step

out of line. This means they do not

learn to regulate their own behaviours right from the start of their

educational journeys as UK-born children do.

New arrivals coming from countries where corporal punishment is still

the norm may therefore struggle and fall foul of UK classroom behaviour

management approaches which they do not comprehend, getting themselves into

endless trouble as they struggle to acquire self-regulation skills with little

or no support. One teacher, dealing with

an incident involving a student from overseas who had hit another child, asked

the former “Would it be OK if I hit you?”

To her surprise, the reply came “Well yes, of course it would.” It was the matter-of-factness of the response

that caused her to realise this child really meant what he had said and that

this was not as straightforward an issue as she had at first assumed.

In other parts of the world,

pedagogical approaches may rest on the premise that children are empty buckets,

waiting to be filled with the knowledge possessed by their teachers. While the teacher teaches from the front, the

children sit at their desks in rows, their success measured by how much they

are able to repeat back in the end of year test. There is little scope for learning through

dialogue or for experimenting with ideas and hypotheses to see which ones hold

true under close examination and which do not.

A child coming from that sort of school experience may struggle to

comprehend what is going on in their lessons in their new, UK classroom. How should they engage with their education

when it looks like this? How should they

now behave and function as learners?

Parents may experience their

own difficulties as they grapple with the apparent vagaries of the UK education

system. They may have found applying

online for a school place challenging enough but that was just the start. If they were used to a system wherein their

child was taught from a textbook that came home every night so they could see

what had been covered during the day’s lesson, then how difficult must it be

for them to keep abreast of their child’s learning when there is no text book

to look at? How then should they recap at home the key points covered in class

each day? How might they help prepare their child for the school day

ahead? If they were familiar with

knowing where in the class ranking their child sat, what sense can they make of

our system where we don’t publish information about each child’s attainment in

comparison to their peers? And if in

their country of origin promotion to the next class depended on their child

passing the end-of-year tests, what must it mean to them in our system where

promotion from Year 4 to Year 5 is automatic, regardless of whether or not the

child has met the end-of-year expectations?

An awareness of the far-reaching impact of living in a new culture that goes beyond a nod and accepts that mere survival isn’t really good enough will help practitioners reflect on how they currently support their international new arrivals and what they might be able to put in place to improve current practice. It is of course still good practice to support children to access the curriculum in English through the planned, purposeful use of first language but if we are to look at the bigger picture, then there is more that can be done to help a newly-arrived child to integrate into their new UK school – not least giving thought to what might be the barriers their parents are facing, and what they can do to reduce or remove them.

Sarah Coles

Consultant (EAL) at Hampshire EMTAS

First published on the ATL blog, July 2017

Further reading and resources

http://www3.hants.gov.uk/education/emtas/culturalguidance.htm EMTAS cultural guidance sheets

http://www3.hants.gov.uk/education/emtas/forparents/parentsandcarersguide.htm

behaviour management guides for parents