Site blog

By Hampshire EMTAS Bilingual Assistant Eva Molea

© Copyright Hampshire EMTAS 2018

I never trusted my mum when she told me that being an EAL parent was not easy. I regret to admit that it has more challenges that I expected. In the first chapter of my diary I went down memory lane, writing about my experience as an EAL child. The second chapter was about how I made my daughter feel comfortable in her new environment. This chapter focuses on strategies I used at home to support learning.

Supporting learning

If helping Alice to settle in could be achieved following one’s own gut feeling, supporting her learning in English needed to be done in a less instinctive way. Before leaving Italy, I had taken Alice to the GP for a check-up and asked if he had any advice about how to support her acquisition of the second language. He told me that he assumed that she would pick it up in school without me doing anything special, but told me that we HAD to speak Italian at home because all the emotional life of a person flows through their first language. So we did, and still do, stick to this rule strictly. It would always be Italian at home or when it is just the three of us, and English when we are with other people.

Since I knew that I would be moving to the UK anytime soon, in September 2014 I enrolled Alice in Year 1 in a private school, so when she started school in the UK she could already read, write and count and she could transfer these abilities to English. I have to say that Alice’s school in the UK was amazing. They made her feel welcome from the very first minute. All the grown-ups would be very nice to her and make sure that she had company and was buddied up with some sensible children. Her teacher in Year 1, Mrs Barton, was just amazing. She was always smiling and positive, and kept her under her wing. Mrs Barton would spot immediately if there was something wrong going on and tell me about it when I went to pick up Alice from school, or call me during school hours if she had some concerns. She knew a tiny little bit of Italian, which she used in the first days to welcome Alice to the class and which gave her the chance to guess what Alice was saying in Italian. She would look up specific words on Google translate to explain tasks or instructions to Alice; she would team Alice up with children who were strong models of language and behaviour and make sure she always had a buddy at playtime and lunchtime. She made all tasks accessible for Alice and would provide her with pictures and visuals, so she could participate in the activities just like any other child. Before reading a new story to the class, Mrs Barton would ask me to go to school at pick-up time to read in advance and translate the book for Alice so that she could follow the story in class the day after.

In Italy, Alice was used to having a literacy and a numeracy task plus reading

every day as homework, so she was very relieved when she found out that, in her

new school, homework was given only once a week and was due the week after. In

fact, she felt so relieved that at the end of the first week she did not even

tell me she had homework to do!! Reading, instead, had to be done every day and

recorded on the reading diary. Alice would come everyday with a book from the

Oxford Reading Tree and we would read it at home. In the first weeks, I would

do a first reading and translation of the book and then she would read it. I

also had to negotiate how many pages I would read to her in Italian and how

many pages she would read to me in English. So once I ended up reading 10 (ten)

Italian books in a row, in order to have her read a tiny little English book

with a line in each page. Life can be tough!

One day Alice came home with a sandwich bag full of pieces of paper with just one word on each. At the beginning I thought it was a puzzle and she had to build sentences with them. But, after a more careful look, I realised there were no verbs, so no sentences could be built. I decided to investigate with Alice, but she had no clue about what they were and why she had been given them. I felt too stupid to ask Mrs Barton about them so, not knowing precisely what to do, I stuck them on the fridge with magnets. A few times she played with them, rearranging them as she preferred, or making shapes on the fridge. After a long time, I found out that she was meant to read them every day. That episode persuaded me to ask a teacher every time I was not sure about what I needed to do. No question is too small.

When it came to writing tasks, they mainly consisted of spelling lists. Every week Alice was given a sheet which had the list of words in a column and then two columns for every day of the week. The task was to read the word, copy it in the first column of the day, cover the word and then write it independently in the second column. I cheated. I made her read it and write it independently both times. A bit of a challenge, but it worked because she used to get all the words right in the weekly spelling tests. This exercise also helped her reinforce her first language and acquire new words because we would translate each word in Italian and explain their meaning.

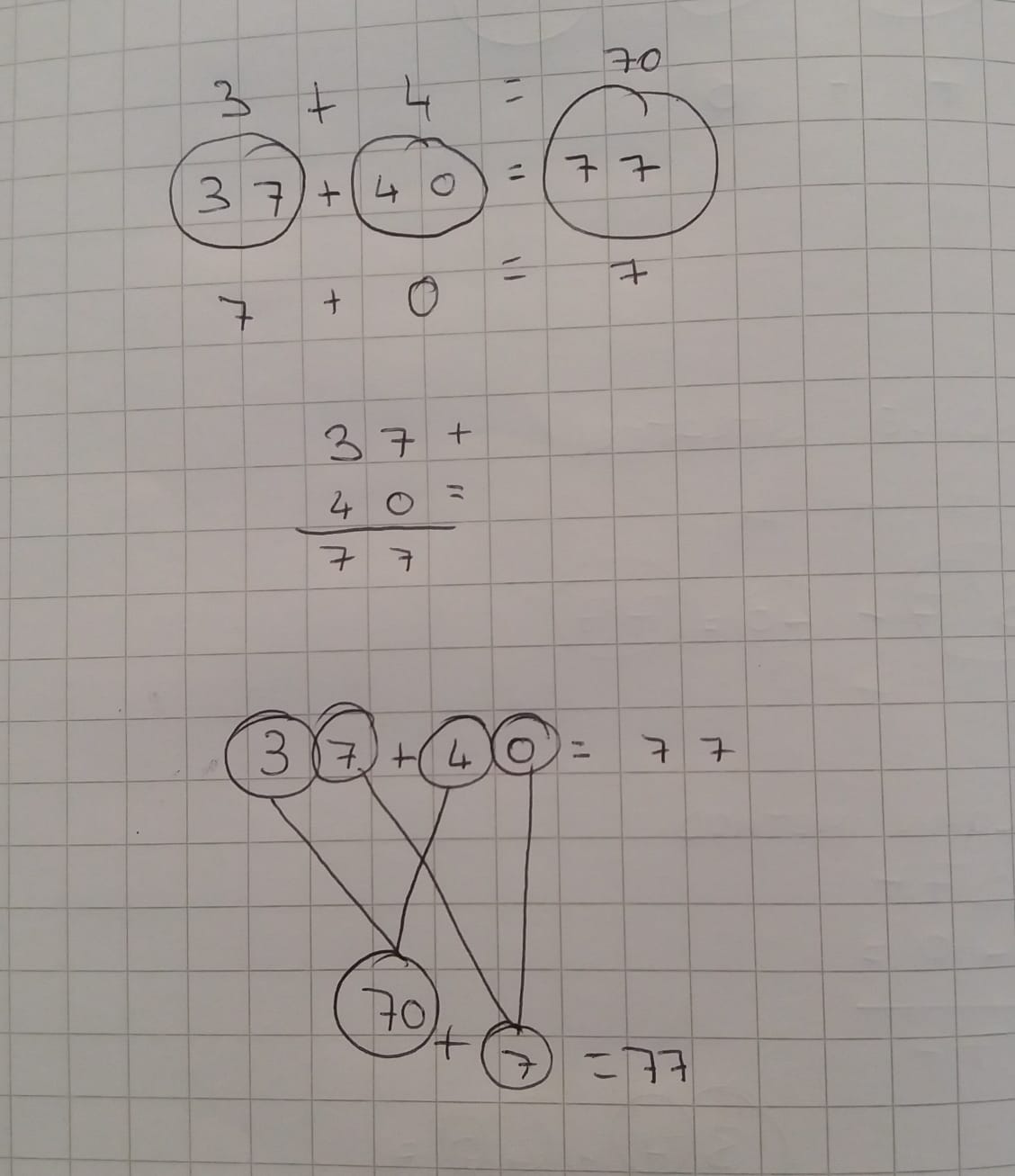

Maths was my nightmare. I know you would think “Year 1 maths a nightmare?? Really??” And the answer is “Yes”. Not because of the difficulty of the tasks themselves, but for the worry of not using the right method to explain things. In the olden days, when I went to school in Italy, we were taught only one method for each operation. To me these are the only options, the easiest ones and the ones that never fail. Can you imagine my face when Alice told me about the “bubble strategy”?? I could only think about a good bubbly drink… Anyway, I resolved to address the maths issues using pegs. Being the “Queen of the Washing Machine”, I had loads of pegs, so I could master additions, subtractions, multiplications, divisions and, ta da, fractions. It was easier for me to explain maths using real objects, things that we could count, move around and “bend” to our needs.

No matter which subject the homework was about, since the beginning we have always done them together and with a dictionary at hand. We have taught Alice how to use the old school dictionary (i.e., the paper copy), but we have also downloaded on all our devices Word Reference, an online dictionary that provides also idiomatic forms and common uses (very useful for verbs whose meaning changes depending on the preposition associated). We still do the daily reading and, luckily, since the end of Year 2 Alice is an independent reader and has access to library books, so no more one-line pages for me. In Years 3 and 4, most homework has been project works or topic works which is really nice because we use literacy and numeracy in different contexts. Alice is a very creative child, so we use lots of colours and ICT, which make the tasks funnier.

A great support in acquisition and development of Alice’s social language came from her school, which offered many after-school clubs at a very accessible price. In Years 1 and 2 she took part in many of them: dance, basket ball, cricket, gymnastic. This was a way for her to be exposed to the use of English in a friendlier context and in an environment she knew. She made lots of new friends in school, and had a bit of fun-time with other children, developing new skills at the same time.

Truth is that, not being a professional, I had no precise recipe on how to support Alice’s acquisition of a second language. It was a trial and error process, a bit like Pavlov’s dogs. All I had to do was to be always positive (which comes easy to me) and patient (much harder, I have learnt many breathing techniques), and when the situation was super-dramatic (which, to tell the truth, happened very rarely) HAND OUT A DELICIOUS PIECE OF CHOCOLATE!!!!! (I know this solution is not the most politically correct one but, trust me, it works!!).

Visit the Hampshire EMTAS website to view information for parents.

Written by Hampshire EMTAS Bilingual Assistant Eva Molea, this is the second instalment in a series of blog posts focussing on the experience of parents of pupils with EAL. Read Chapter 1 before enjoying this new post.

March 2015

I needed a strategy. And a pretty good one, too. I needed to make my daughter Alice’s life in the UK enjoyable, cure her homesickness and support her learning. Any of these tasks on their own would have been hard enough, but all together I was not sure I could make it. So, I rolled up my sleeves and started working on our new environment.

An enjoyable life in the UK

The first thing I had to do was to make Alice comfortable

in her new house. So, we made a lovely and cosy room for her, with some of her

toys from Italy, many books in Italian and some in English (now we have loads of

both and we do not know where to put them…). Since she was in the “pink

period”, we chose some of the furniture accordingly, and some decorations as

well. We showed her where everything was in the house, so she could quite

independently have access to what she needed. We taught her how Sky worked, so

she could watch TV whenever she wanted. At the beginning, we allowed her to

watch much more TV than we normally would, but we believed that TV would offer

a good model of English, so she had free access to it for quite a while. In the

first days, she would just watch “Tom & Jerry” or the Warner Bros. cartoons,

as she could follow the story even if she did not speak a word of English. Then

she gradually moved to other programmes without our suggestion, and soon

started to watch feature films, even if with a bit of a struggle.

Then we moved to explore the surrounding area. We went to the adventurous discovery of the neighbourhood and then of our small town. We took her to the playgrounds and to the cinema, to the local museum for a play day on dinosaurs, shopping for her school uniform and for food, encouraging her to try new flavours. We took her for a full English breakfast and to eat out. In general, unless it was raining cats and dogs, we took her out every week-end, even if it was just for a walk into town. But the best thing we did was to enrol her to the dance school at the local leisure centre. Since she was very little, she had asked me to go to a dance school, so now she was in for a treat. It turned out to be a great decision because Alice had the chance to meet with other children and make different friends from the ones she had at school. Also, since she had already practised sports in Italy, she knew she had to imitate the teacher, so she could join in quite easily. Her dance teachers were lovely and this helped a lot. She still dances three times a week with the same eagerness of the first days.

Defeating homesickness

To overcome homesickness was definitely a harder task. Alice missed her grandparents, her friends, her teachers, and the entire little universe she was used to live in. We tried to recreate the life she had in Italy: we did not change habits, but stuck to the usual routines. Doing everyday exactly the same things that she was used to in Italy made Alice feel safe and secure. She knew what was coming next, and these little certainties helped her find her way through the bigger changes our lives were going through.

The other thing that was very helpful was that I did not work at that time. We had decided, with my husband, that I would have not looked for a job until September 2015, because I wanted to make sure that Alice had settled in nicely and everything was going well. My husband had moved to the UK in 2013, so Alice and I had been on our own for quite a long time. At that time, I used to work from Monday to Friday from 4.30 to 8 pm. This meant that Alice had to stay with the grandparents, who would alternate in the babysitting during the week. She was looking forward to an intense one-to-one time with mummy, which was served to her on a silver tray when we moved to the UK. She really made the most of it: she would ask for girls’ night in, to go to the cinema, to go shopping. Basically, she really enjoyed being part of a team of two. Yahoo!!

Technology also played an essential role in defeating homesickness. Daily video-calls with the grandparents made distances smaller, and Alice would happily take the tablet to her room and talk to them about her day or play games with them on Skype. We often spoke to our closest friends via Skype, so the children also kept in touch. This also created great excitement the first times we went back to Italy, because they would not feel like strangers when they met after a long period.

So far so good, but now how was I going to help her with her learning since I am an EAL person myself? And with a strong Italian accent too (they say)? Find out in the next chapter of my Diary of an EAL Mum! In the meantime, why not browse the 'For Parents' tab on the Hampshire EMTAS website?

A small scale piece of research into the ‘Any other White background’ (WOTH) ethnic group in Basingstoke & Deane painted a fascinating picture of the experiences of Polish families in UK schools. Parental engagement and home-school communication emerged as an important area for both parents and practitioners – and an aspect of EAL practice that can be difficult to get right.

What are the challenges?

Despite schools’ best efforts, induction can be a delicate time. Parents may struggle to get to grips with school systems, such as getting uniforms right, understanding timetables, knowing how to pay for school dinners, learning about the purpose of different virtual learning environments, etc. – whilst having to fill out forms in an unfamiliar language.

Keeping up to speed with the school calendar might be another difficulty. Parents of EAL learners may struggle to understand letters concerning events such as parent evenings, trips, data collection, and other special occasions such as sports days and INSET days. In fact, the very use of acronyms such as ‘INSET’ is sometimes another hurdle for EAL parents who are new the UK system and often also new to English, especially when these acronyms can be confused for a common everyday term like ‘insect’!

Parents are very keen to support their children with homework and whilst subject knowledge may not necessarily cause them concern, instructions and key words are more problematic due to the more academic nature of the language. However most of all, parents seem to struggle with never being quite certain whether or not they are in the loop. Often, support comes in the form of an EMTAS Bilingual Assistant who is able to interpret for school systems, routines and curricula. Watch this video clip to learn about their experience.

What’s helpful?

In addition to the use of bilingual staff, parents find a simple text message is very helpful in reinforcing the content of school letters, especially when these contain a lot of information to process. Text messages offer condensed details highlighting the most important facts e.g. dates and times of meetings, things to bring to school, reminders, etc. and help parents to keep track of what is happening and when. Yet this is not always a system in place in all schools.

Other parents are another important resource for families. When unsure about any aspect of school life, EAL parents may look to other parents – EAL as well as English-only. However whilst other parents may be a source of reassurance for some, those who aren’t confident with their English to approach other parents may continue to feel lost and isolated at pick up and drop off times. Some schools have tackled this issue by approaching established parents to become helpers in order to offer support to newly-arrived families.

Receiving feedback from their child’s teacher at the end of the day is another way for parents to feel reassured. In our study, EAL parents said they appreciated school practitioners initiating a conversation about how the children had coped during the day, what they had achieved and what they needed to work on. Sometimes, a thumb up and a word of praise was enough to alleviate parents’ anxieties. This was even more appreciated when parents weren’t confident to take the first step to approach staff themselves. In some cases, EAL parents still felt they were only approached by classroom staff when their child had done something wrong.

EAL parents spoke about the advantages of knowing what was coming up in class from one week to the next. This gave them opportunities to discuss topics in advance at home and in their first language, allowing their children to take a more active part in lessons. Parents found general information shared on the school website about what the children were to learn over the half-term less useful because this information contained less details and didn’t focus on the particular needs of their child.

Next steps

A network meeting was held in Basingstoke to share findings from the research with local infant, junior and secondary EAL practitioners. Delegates discussed specific aspects of home-school liaison they wanted to improve at their school and collaborated on a checklist. To follow up on the practice discussed at the network meeting, practitioners at The Vyne School organised a coffee morning event for parents of EAL learners joining Year 7. The event was attended by key staff along with the school’s Young Interpreters who spoke to the children and families and gave tours of the school. The event was well-attended by pupils and parents from a range of feeder Primary schools who felt supported in their transition to Secondary education.

What action would you take to help improve home-school liaison at your school? Over to you now: read the full research report, learn about the First Language in the Curriculum (FLinC) project, set up the Young Interpreter Scheme® and share the strategies you have found most successful at your school in the comment box below.

Written by Hampshire EMTAS Bilingual Assistant Eva Molea, this is the first instalment in a series of blog posts focussing on the experience of parents of pupils with EAL.

March 1980

Many moons ago, when I was nearly 5, my dad decided to apply for a temporary position as plastic surgeon at Queen Victoria Hospital, in East Grinstead, and was luckily appointed. So, we packed our entire house, the useful and useless (silver cutlery included because one could never ever think of dining without one's own silver fork!), loaded our blue Alfetta and embarked on the three day trip that would change our lives.

It was early 80s, and a very exciting time to be at Queen Victoria Hospital with many other people from all over the world: Australians, French, Israeli, Egyptians, Irish, Italians, just to name a few. And, obviously, some Brits as well! It was also very exciting for us children, all attending the same primary school.

This is the background of my personal experience as an EAL child. I will not say that it was easy at the very beginning - name it the first month. The sense of deep isolation for not having a child to talk to and who understood me was overwhelming and my mum, who did not speak a single word of English, had to do everything in her powers to keep me entertained.

Then I started going to school in Year 1 and it was a blessing. My mum felt relieved (and we all know that a happy mum has happy children) as I picked up the language very quickly and made many friends, making her juggling skills no longer needed.

Besides taking me out of my linguistic isolation, the school gave me much more: thanks to the empiric approach of the British scholastic system, I developed strong observational skills and a genuine curiosity towards what I was being taught, which have been my main features through all my years at school and university. It taught me to challenge what I was learning to prove it right. It helped me develop a very rational approach to everything and the ability to analyse. Should it not be clear enough, I am still very grateful to the system. Also, the environment was amazing: massive playground with forts and a field at the back which had no boundaries. My classroom was big enough to host 30 children, plus a play-pretend corner, a big carpet, loads of toys and walls covered with pictures and resources to support our learning.

Unfortunately, my EAL experience came abruptly to its end after just one year because my dad's contract expired and we repacked all our house plus some other souvenirs, loaded again our Alfetta and headed south. Back to Naples, Southern Italy. I could have never imagined, at the time, that my own daughter would follow my steps.

February 2015

We packed our house, with all its useful and useless clutter, shipped it to the UK - how smart! - and moved in February 2015, my daughter being nearly 6 and halfway through Year 1. Strong from my personal experience, I moved quite light-heartedly. At the end of the day, how hard could it be?? This is when I learnt that every child is different, despite genetics. It also made me understand that I had always seen the whole issue of moving from a happy child's perspective, not from a sensible adult's one. I was not prepared. Not at all.

Fortunately, school started one week after we arrived, and with a school trip to the HMS Victory on day 1. What a great start! A. was very impressed and this put her in a good disposition towards her new school. As soon as her teacher introduced her to the class, a girl came and took her to line up. An unexpected act of kindness that changed one of my most dreaded days into a lovely and very informative school trip - did you know that when Admiral Nelson died he was put in a barrel of rum to be preserved for his funeral?

But the linguistic isolation struck her quite soon, so we had the before-going-to-school tantrum and the after-school one. The "I want to go back to Italy right now" desperate cry and the unintelligible sobs that showed all her frustration at not being able to function as well as she was used to in Italy.

But I was not prepared to give up. Nor to let her do so.

To be continued… Come back soon to read the next chapter of this unique parent diary, using the tags to help you.

Visit the Hampshire EMTAS website for information and guidance on how to help settle a newly arrived pupil into school.

written by Jamie Earnshaw, Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor

A small scale piece of research into the ‘Bangladeshi’ (ABAN) ethnic group in Eastleigh offers an insight into the experiences of Bangladeshi families in UK schools

Bangladeshi families in

Eastleigh have generally been settled in the town for many years. In fact,

Bangladeshi children going through the education system now tend to be UK born

and are often the second or third generation of their family to attend school

in the UK. However, school data for the ABAN group suggest they are behind many

other ethnic groups, particularly in the primary phase, in English and Maths.

Observations of pupils in class illustrate how settled and integrated ABAN pupils are in primary schools; ABAN pupils were seen to be actively participating in the classroom in both collaborative and independent activities, often taking the lead when presenting back to the rest of the class during group work. Discussions with school staff paint a similar picture; anecdotally, ABAN pupils are as engaged and as settled in the school environment as any other pupil. Of course, this has not happened by chance but is the direct result of quality first teaching, in which good practice strategies for supporting EAL pupils are embedded. The mismatch between the anecdotal evidence pointing to how ABAN pupils should achieve in school, compared with the factual data, is therefore quite a quandary.

At home, parents of EAL learners often battle with the decision over whether to forgo the use of first language in a pledge to support their child’s acquisition of English, despite this being the antithesis of good practice advice. With Bangladeshi families in Eastleigh, this is not so. At home, first language is used, often exclusively, between parents, their children and the wider family. The only time pupils tend to use English at home is with a sibling, normally when they are working on a piece of homework or playing a game.

For pupils, the desire to discuss homework in English is often as a result of the academic nature of the language which they have learnt and used solely in the classroom where the language domain is English; specific vocabulary for topics like Ancient Greece or the transference of forces in gears and pulleys is unlikely to be used in day-to-day family life. It is perhaps therefore understandable that pupils might choose to use English to support with the completion of homework. However, as a result, parents can often feel ostracised from their children during this time.

Unlike parents of newly arrived EAL pupils, the usual potential barriers for ABAN parents are not as prevalent. After all, ABAN parents in Eastleigh have often gone through the education system themselves. Parents tend to know what the school systems are, they understand about school events such as closures or non-uniform days and, according to school staff, frequently attend parents’ evenings. Dialogue between home and school, on the surface, is not an issue.

The unquestionable desire for parents to support their children at home, yet not feeling equipped to do so, appears to lie incongruently with the established links between home and school. Perhaps the best comparison is that of the advanced learner of English in the classroom; such pupils often do not receive the support they require due to them blending in, being able to partake in conversations, coupled with not wanting to identify themselves as being different by asking for additional support, for example. This is the dilemma parents often face. The general expectation of reinforcing at home what has been learnt in the classroom is understood, but addressing the finer details of actually being able to support in this role is often the pitfall.

The compartmentalisation of English for academic purposes and first language for family time can inhibit the identification of ways to build on what a child learns in class. Many ABAN pupils are not able to read and write in first language yet contrast this with the fact that parents are often confident when speaking conversational English but have low levels of literacy in English (coupled with low literacy levels in first language too). Consequentially, families tend not to have texts in any language they can share with their children at home. Additionally, the relative economic deprivation and lack of cultural capital in Eastleigh, exacerbated by the fact that often families do not have a car to travel out of the area, means that opportunities for learning in other contexts are rather limited.

The solution?

Of course, there is no one-size-fits-all answer. Key, however, must be continuing to build on the established links between school and home, in order to facilitate further exploration and open dialogue of how parents can support at home. Playing on parents’ strengths is essential; whether that’s sending home key questions for parents to ask in first language in order to evaluate their child’s prior learning, or sending home dual language texts as a way of sharing the learning process between parent and child. Recorded audio instructions might also help, alongside sending home differentiated materials used in the classroom, in advance, just to give parents confidence to get involved in supporting their children at home. Additionally, help with identifying opportunities for learning in other contexts away from school might also be beneficial.

This blog may well leave schools and parents with more questions than answers. Nevertheless, it has certainly shone a light on how well integrated ABAN pupils are in schools, which is testament to the hard work of schools, families and pupils. Through encouraging further open dialogue between home and school, the trajectory for ABAN pupils in Eastleigh can only be positive.

Further reading and resources

http://www3.hants.gov.uk/education/emtas/forparents/parentsandcarersguide.htm

https://eal.britishcouncil.org/teachers/parental-engagement

written by Sarah Coles, Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor

It is usually clear to staff in schools that there is a

support need they should address when a newly-arrived pupil from overseas

experiences a language barrier on joining their first UK school. This may be the child’s first experience of

being in an English-speaking environment, and there is much to learn in terms

of the new language. What are less

discernible – and perhaps less well-supported - are the other barriers such a

child may face – barriers that relate to differences in pedagogy, social and

cultural differences and of course the sense of dislocation and loss the

newly-arrived child may feel when they first start, having left behind all

their friends and possibly family members too.

Being placed in a situation far outside of their comfort zone, there is

a lot for a new arrival to manage in addition to the demands of having to cope

in a new language.

In the UK, pedagogical

approaches focus on children learning through experience, learning from each

other, learning through trial and error, learning through talk. From an early stage, our indigenous,

monolingual children learn how to learn in these ways and teachers, many

themselves a product of this same system, teach from an often deeply-rooted

belief that these ways are the best. We

are so immersed in the UK classroom culture that as practitioners we may forget

it’s not like this everywhere in the world.

In Poland, for example,

children do not come to sit on the carpet to learn as the carpet is perceived

to be a dirty surface that’s walked on by everyone, so a Polish child – and

possibly also their parents - may look askance when the class is directed to

come to sit there for story time.

In some countries,

children’s behaviour is managed for them,often with a stick should they step

out of line. This means they do not

learn to regulate their own behaviours right from the start of their

educational journeys as UK-born children do.

New arrivals coming from countries where corporal punishment is still

the norm may therefore struggle and fall foul of UK classroom behaviour

management approaches which they do not comprehend, getting themselves into

endless trouble as they struggle to acquire self-regulation skills with little

or no support. One teacher, dealing with

an incident involving a student from overseas who had hit another child, asked

the former “Would it be OK if I hit you?”

To her surprise, the reply came “Well yes, of course it would.” It was the matter-of-factness of the response

that caused her to realise this child really meant what he had said and that

this was not as straightforward an issue as she had at first assumed.

In other parts of the world,

pedagogical approaches may rest on the premise that children are empty buckets,

waiting to be filled with the knowledge possessed by their teachers. While the teacher teaches from the front, the

children sit at their desks in rows, their success measured by how much they

are able to repeat back in the end of year test. There is little scope for learning through

dialogue or for experimenting with ideas and hypotheses to see which ones hold

true under close examination and which do not.

A child coming from that sort of school experience may struggle to

comprehend what is going on in their lessons in their new, UK classroom. How should they engage with their education

when it looks like this? How should they

now behave and function as learners?

Parents may experience their

own difficulties as they grapple with the apparent vagaries of the UK education

system. They may have found applying

online for a school place challenging enough but that was just the start. If they were used to a system wherein their

child was taught from a textbook that came home every night so they could see

what had been covered during the day’s lesson, then how difficult must it be

for them to keep abreast of their child’s learning when there is no text book

to look at? How then should they recap at home the key points covered in class

each day? How might they help prepare their child for the school day

ahead? If they were familiar with

knowing where in the class ranking their child sat, what sense can they make of

our system where we don’t publish information about each child’s attainment in

comparison to their peers? And if in

their country of origin promotion to the next class depended on their child

passing the end-of-year tests, what must it mean to them in our system where

promotion from Year 4 to Year 5 is automatic, regardless of whether or not the

child has met the end-of-year expectations?

An awareness of the far-reaching impact of living in a new culture that goes beyond a nod and accepts that mere survival isn’t really good enough will help practitioners reflect on how they currently support their international new arrivals and what they might be able to put in place to improve current practice. It is of course still good practice to support children to access the curriculum in English through the planned, purposeful use of first language but if we are to look at the bigger picture, then there is more that can be done to help a newly-arrived child to integrate into their new UK school – not least giving thought to what might be the barriers their parents are facing, and what they can do to reduce or remove them.

Sarah Coles

Consultant (EAL) at Hampshire EMTAS

First published on the ATL blog, July 2017

Further reading and resources

http://www3.hants.gov.uk/education/emtas/culturalguidance.htm EMTAS cultural guidance sheets

http://www3.hants.gov.uk/education/emtas/forparents/parentsandcarersguide.htm

behaviour management guides for parents