Site blog

by Smita Neupane and Sudhir Lama, Nepali Bilingual Assistants with Hampshire Ethnic Minority and Traveller Achievement Service

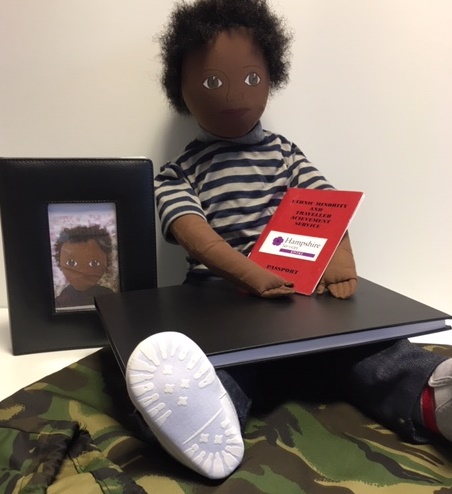

Have you ever used a Persona doll? Do you know how and why to use a Persona Doll? Persona Dolls are an ELSA resource and emotional literacy support tool used to initiate talk and to share experiences within the classroom. EMTAS were awarded an amount of money in an MOD bid to work with Infant and Early Years settings to introduce Personal Dolls to help all children cope with the demands of moving school, house, and even country with a particular focus on Service children. The Persona Doll project is also designed to involve the family and community and to share experiences with peers. It has an intergenerational element with the involvement of secondary pupils supporting the creation of some of the resources.

In the beginning…

Hampshire is an area rich with Service children across the length and breadth of the county and spanning all the educational phases. The project is designed to support Early Years children but to make it relevant, the experiences of older children was needed and had to be included in the package.

Initially, before the Persona Dolls had joined us, the work started at The Wavell School, with two Nepali Bilingual Assistants from Hampshire Ethnic Minority and Traveller Achievement Service (EMTAS) interviewing students with backgrounds from Fiji, Nepal, Malawi and Jamaica. They shared their stories and were open and honest about their experiences including the difficulties faced during transition and the worries about having a parent in the forces. They spoke of homesickness and missing friends and family, the foods they missed and aspects of their lives that had changed. Some of the students were UK born so had not lived in their parents’ country of origin so they took time to find out as much about their culture and history as they could through their families and community. The students created talking books from this information that included pictures and speech both in English and first language. Some of the books included nursery rhymes from their culture and how to count in their first language. The books are proactive and help bring the Persona Dolls alive. The Wavell children chose the dolls and named them ready for their journey into their schools.

First steps…

When the Talking books were all prepared and each Persona Doll had its name and a passport produced, they were packed up ready to travel with their big note book to record their experiences. The dolls have been taken to infant and primary schools all over the county and the idea is that they stay in that school for roughly half a term and then they are off on their travels again. The doll is taken into the school and introduced into the class where it will be staying and the children get to ask it questions and to find out what it likes and dislikes.

Some ground rules were set:

- doesn’t matter how dirty the doll gets

- no face painting, hands or feet painting of the doll!

- it is not to be used as a reward

- it has to be included on the register

- it has to have its own seat, peg etc.

- it has to have lots of different experiences

- everything has to be recorded in the Persona Doll’s book and shared.

The first doll to leave EMTAS was Himal, a Nepali boy, and he went off to Talavera Infant school and Becky the class teacher. Becky and the class totally embraced this project and the work was amazing. Himal attended an Eid festival where he was gifted new shoes. He went to a Christening. He went to a hot tub party (but just watched). He also shared his feelings about moving to a new school and how this made him feel.

The Persona Dolls generate lots of discussion with the children. It encourages them to think about how they feel when they experience trying something for the first time. It makes them think about what a good friend is and how a good friend can support a new arrival. It allows the children to talk about things that may worry them about transition and about what is happening in their lives at home and at school.

Desired outcomes …

It is hoped that the eight dolls will continue to transition from setting to setting and may even revisit schools they have been to already as can happen with Service children.

One of the aims of the project was to help build up pupil self esteem and confidence. It is hoped that through exposure to the stories children will want to talk and share their own feelings and experiences. Through listening to each other’s experiences it helps children realise that they are not alone in what they are feeling and it is okay to feel that way.

While the project has a fun element of taking the doll to different celebrations and events it is also teaching social and emotional skills through communication and responsibility.

The feedback so far from two schools has been very positive and the children have loved having their guest to stay and were really sad when they left. This too helped teach pupils resilience as many children feel unhappy and lost when their best friend moves on and this helps them build up coping strategies to deal with this and invites discussion within the classroom to look at feelings.

Do you want to be part of this?

If you are a Hampshire school and would like to be part of this ongoing project please email Claire Barker, claire.barker@hants.gov.uk. We would be delighted to have you come on board and training is available this term.

Please see our website for further information on the use of Persona Dolls.

If you are a school outside Hampshire and would like a chat about how to set this up in your area, please contact Claire Barker, claire.barker@hants.gov.uk.

Sarah Coles shares the start of her PhD journey with the first two instalments of a journal-style account of her reading for the literature review and methodology chapters of her thesis. She is planning to research the language learning journeys of UK-born EAL learners as they enter Year R but before entering the field, there are books and articles to be read and planning to be done.

Week 2 of Term 1 (2018-19) and the summer has faded in more ways than one, which coincides with an interesting bit of a book I have been reading for my PhD. The book is about Second Language Acquisition and makes the point that most research into this has a focus on learning the new language. While this is of course interesting with many, often competing, views vying for attention in the literature, the authors suggest that language attrition – or ‘forgetting’ – is equally interesting. They say that all our languages form part of a complex, dynamic system in our brains that changes continuously and they put forward a simple rule which states that information we do not regularly retrieve becomes less accessible over time and ultimately sinks beyond our reach. In relation to our languages, these are in a constant state of flux, they argue, depending on the degree of exposure we have to each. Talking to colleagues about this in the EMTAS office, they said they had noticed changes in their own languages over time. Kamaljit talked about how her ability to write in Hindi has decreased due to lack of use, whilst Ulrike and I had both experienced difficulties with word retrieval and with one language affecting the other in different ways. For instance sometimes, because of immersion in Turkish all those years ago, I would respond in Turkish to members of my immediate family who don’t speak the language when I went home for a holiday. They were grateful that this passed fairly rapidly, though I observe my languages have been shuffling around in my mental filing cabinet ever since. Mostly, English sits at the front and comes out first, Turkish is a bit further back but in front of French, pushing French out of the way when I am in France much to the bemusement of the French – the majority of whom don’t speak Turkish either.

Week 3 of term 1

Alongside the day job, I have carried on reading for my PhD studies and my focus this week has been on qualitative research methods. One thing I need to consider carefully is my own impact on the situations I will be researching because even if I am only there to observe, this in itself will influence not only what happens but also how I interpret what I see. Clearly in a classroom situation you cannot see absolutely everything that happens, never mind be able to record it all in handwriting that you can read back afterwards. There will be much that you don’t see at all, and also much that you do see but that you don’t record – which isn’t to say it’s not useful or relevant to the area of research, just that there will be inevitable casualties due to the pragmatic aspects of what you’re able to do as the researcher. Anyway, the long and short of it is that researcher bias is something I will need to be aware of as according to several different authors, you can’t remove it from the equation. Rather, you need to be aware of your point of view, your previous experiences and prior knowledge and how these things colour the way you see and hear and interpret events in order to manage the impact of your own bias on your research. It is interesting to me to consider too how language and cultural differences might impinge on methods like interview, and there is a lot to think about when you are planning to use this as a tool to elicit data from people. You could, for instance, have a set of predetermined questions and you could just ask people those. Or you might find this too interrogative a way of doing an interview which just doesn’t fit with what you are trying to achieve – which in my case is a full, rich picture of people’s lived experiences and views. So I am thinking about a more flexible approach, possibly around doing some mapping of languages, people, communities and the like while people talk, which won’t look much like the sort of interview I mentioned first but will hopefully give me the sorts of data I am looking for. I have yet to read the chapter on coding, so there is a chance I may change my mind about this. Keep tabs on the journey as it unfolds using the tags below.

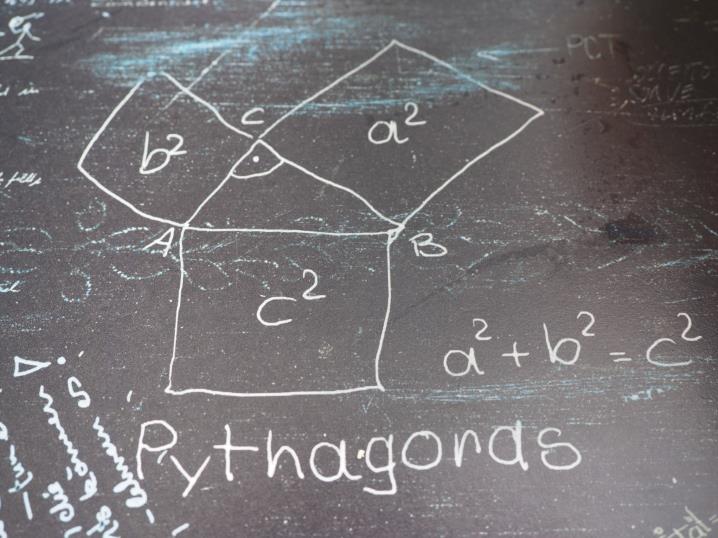

There is a commonly held notion that mathematics has a universal quality that ensures learners have a relatively equal opportunity to succeed, whatever their background. But is this generally true when it comes to pupils learning English as an additional language (EAL), or does it require qualification and a much more nuanced analysis?

Introduction

It can’t have escaped your attention, whether as an educator or parent, that there is some angst nationally over standards in mathematics compared with other nations. Whether this is a genuine problem and that the root causes can be easily explained is for another article. However, it is true that the UK differs from many other countries in the amount of language that is deliberately interwoven into the mathematics curriculum. This is important as the expression of mathematics through a linguistically rich curriculum may present barriers for learners who are not working at age-related expectations in English. This approach might also present cultural inhibitors, whether because children lack a degree of cultural capital as result of their upbringing or because they and/or their parents were educated abroad.

Pupils educated abroad

Pupils educated abroad, especially older EAL learners who have had an uninterrupted education, will have studied a lot of mathematics; finding out about their mathematical experience and ability can be problematic when they first arrive. However, it is true that mathematics is one subject in which newer to English learners have some chance to demonstrate their prior learning because it is less dependent on language than many other subjects. Testing and baseline assessment of mathematics can be helpful but the results need to be treated with caution. Whilst it is tempting to assume that mathematical approaches are similar across the world, the reality is very different. Numbers are not just numbers when a learner has routinely used different numerical symbols to the Hindu-Arabic numerals used in Western society. Not only this, but symbols, like an equal sign or a multiplication symbol, can be denoted differently. The fabric of the curriculum differs widely as well. We often find children are way ahead in certain disciplines such as algebra or calculus yet have limited knowledge of others like shape or perimeter. The mechanics of solving problems are such that a child may be secure in a method which is entirely different to those taught in UK Schools. Indeed, children abroad are not necessarily routinely taught several different methods and may find it hard to consider alternative ways of approaching a problem, particularly if they are already secure in one way.

The mathematical problem

As I am sure you are aware, our mathematical problems tend to be very wordy and the way that questions are expressed, particularly in exams, can be difficult for some EAL learners. The English is stylised, particular to mathematics and quite unlike the way that we talk or even write on a daily basis. I would also argue that most mathematical questions are culturally bound, making implicit assumptions about what experiences pupils will or will not have had, whether UK born or not.

To illustrate this quandary, consider the following problem:

At yesterday’s match 650 people watched Arsenal play on the big screen. Half of these fans bought a programme at £2.50 each.

- How many fans paid out?

- How much money was spent on programmes altogether?

Firstly, this question like many you will see in examination papers, lacks a comprehensively clear context. There are no visual clues and the setting, related to a football match, is implied but not explicitly referenced. If you don’t know about ‘Arsenal’ you are at an immediate disadvantage. The problem revolves around buying and selling ‘programmes’ which may be beyond many pupil’s experience if they have never attended a football game. The use of the word ‘programme’ is problematic as it can all too easily be linked with the phrase ‘watching on the big screen’ and interpreted as a TV programme. Like the word ‘programme’, there are other homographs as well, such as ‘match’ and ‘fan’ which may cause confusion. The relevant numerical operation is bound up in words like ‘each’ and ‘altogether’; words like this that imply a specific numerical operation, and there are many, need to be explicitly taught to EAL learners. The question also features the phrasal verb ‘paid out’; this type of language is extremely hard for English beginners.

The implications for EAL learners are far reaching. If you are working with children at an early stage of English acquisition you will need to consider both the linguistic and cultural demands of the mathematics curriculum. Making the mathematics more comprehensible will require thought and preparation - whether through the use of imagery, first language explanation, mathematical glossaries or other forms of personalisation.

written by Sarah Coles, Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor

It is usually clear to staff in schools that there is a

support need they should address when a newly-arrived pupil from overseas

experiences a language barrier on joining their first UK school. This may be the child’s first experience of

being in an English-speaking environment, and there is much to learn in terms

of the new language. What are less

discernible – and perhaps less well-supported - are the other barriers such a

child may face – barriers that relate to differences in pedagogy, social and

cultural differences and of course the sense of dislocation and loss the

newly-arrived child may feel when they first start, having left behind all

their friends and possibly family members too.

Being placed in a situation far outside of their comfort zone, there is

a lot for a new arrival to manage in addition to the demands of having to cope

in a new language.

In the UK, pedagogical

approaches focus on children learning through experience, learning from each

other, learning through trial and error, learning through talk. From an early stage, our indigenous,

monolingual children learn how to learn in these ways and teachers, many

themselves a product of this same system, teach from an often deeply-rooted

belief that these ways are the best. We

are so immersed in the UK classroom culture that as practitioners we may forget

it’s not like this everywhere in the world.

In Poland, for example,

children do not come to sit on the carpet to learn as the carpet is perceived

to be a dirty surface that’s walked on by everyone, so a Polish child – and

possibly also their parents - may look askance when the class is directed to

come to sit there for story time.

In some countries,

children’s behaviour is managed for them,often with a stick should they step

out of line. This means they do not

learn to regulate their own behaviours right from the start of their

educational journeys as UK-born children do.

New arrivals coming from countries where corporal punishment is still

the norm may therefore struggle and fall foul of UK classroom behaviour

management approaches which they do not comprehend, getting themselves into

endless trouble as they struggle to acquire self-regulation skills with little

or no support. One teacher, dealing with

an incident involving a student from overseas who had hit another child, asked

the former “Would it be OK if I hit you?”

To her surprise, the reply came “Well yes, of course it would.” It was the matter-of-factness of the response

that caused her to realise this child really meant what he had said and that

this was not as straightforward an issue as she had at first assumed.

In other parts of the world,

pedagogical approaches may rest on the premise that children are empty buckets,

waiting to be filled with the knowledge possessed by their teachers. While the teacher teaches from the front, the

children sit at their desks in rows, their success measured by how much they

are able to repeat back in the end of year test. There is little scope for learning through

dialogue or for experimenting with ideas and hypotheses to see which ones hold

true under close examination and which do not.

A child coming from that sort of school experience may struggle to

comprehend what is going on in their lessons in their new, UK classroom. How should they engage with their education

when it looks like this? How should they

now behave and function as learners?

Parents may experience their

own difficulties as they grapple with the apparent vagaries of the UK education

system. They may have found applying

online for a school place challenging enough but that was just the start. If they were used to a system wherein their

child was taught from a textbook that came home every night so they could see

what had been covered during the day’s lesson, then how difficult must it be

for them to keep abreast of their child’s learning when there is no text book

to look at? How then should they recap at home the key points covered in class

each day? How might they help prepare their child for the school day

ahead? If they were familiar with

knowing where in the class ranking their child sat, what sense can they make of

our system where we don’t publish information about each child’s attainment in

comparison to their peers? And if in

their country of origin promotion to the next class depended on their child

passing the end-of-year tests, what must it mean to them in our system where

promotion from Year 4 to Year 5 is automatic, regardless of whether or not the

child has met the end-of-year expectations?

An awareness of the far-reaching impact of living in a new culture that goes beyond a nod and accepts that mere survival isn’t really good enough will help practitioners reflect on how they currently support their international new arrivals and what they might be able to put in place to improve current practice. It is of course still good practice to support children to access the curriculum in English through the planned, purposeful use of first language but if we are to look at the bigger picture, then there is more that can be done to help a newly-arrived child to integrate into their new UK school – not least giving thought to what might be the barriers their parents are facing, and what they can do to reduce or remove them.

Sarah Coles

Consultant (EAL) at Hampshire EMTAS

First published on the ATL blog, July 2017

Further reading and resources

http://www3.hants.gov.uk/education/emtas/culturalguidance.htm EMTAS cultural guidance sheets

http://www3.hants.gov.uk/education/emtas/forparents/parentsandcarersguide.htm

behaviour management guides for parents