Site blog

By former EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Jess Richards

It’s one thing to be an advisor helping other people welcome new arrivals. It’s quite another when your family become the new arrivals themselves.

At the start of 2024 my husband and I relocated to Texas with our two children. To be absolutely clear, we are in a privileged position. We weren’t escaping conflict or instability, we had the support of a big corporate employer and – most significantly of all – we didn’t have a language barrier to overcome. Nonetheless, moving several thousand miles with kids has been a real education for this so-called ‘specialist’.

I am pleased to say I have seen a lot of excellent practice. My daughter arrived in Kindergarten in the middle of the school year and was literally welcomed with open arms. Teachers stood outside on her first day with signs like an airport arrivals lounge to make sure she knew where to go. They were visibly excited to meet her and make her part of the school community. We received lots of information about aspects that were completely new to us: riding the bus or joining the car lines for school pick up, buying school supplies. Despite the frequency of accepting new students from overseas it hadn’t dampened their enthusiasm. Not once did our arrival feel like an added burden in their busy schedules. School spirit and belonging wasn’t just theoretical; they were living it out every day.

There’s an infographic sometimes used in EMTAS training with concentric circles showing the concerns of newly arrived students. The outside circle is the least complex, applying to any child at a new school without the added burdens of language acquisition or forced displacement. This is the circle where my family sits. Will I make friends? Will I know where to find the toilet? Will they have food I like? These are easy to solve but often overlooked. I have a new appreciation for them now. When you’re operating in a totally different education system, the little things really matter.

What did my children find most challenging? Ironically, my six year-old daughter says it’s the language. She’s a first language English speaker in a first language English setting and yet she’s still navigating linguistic differences every day. We tried to prepare her for the obvious: restrooms, recess, trash. Others she learned by inference or plain old misunderstanding: band aids, tennis shoes, braids. Luckily she isn’t alone in a big expat community and she’s socially confident. A shy child might have found it quite tough.

The linguistic challenges for my three year-old son have been much more stark. Still early in his own English language journey, he had less context to help him piece things together. We talked about the ‘bathroom’ and the ‘restroom’ and his ‘pants’ but didn’t realise how frequently he would be asked, ‘do you need to go potty?’ Once he worked out it was ‘potty’ not ‘party’ (accents are tricky when you’re three!) he still thought it wasn’t for ’big boys’ like him. He assured them in no uncertain terms that he uses the toilet.

Our move has also taught me a lot about an aspect we sometimes overlook: cultural difference. I felt I had lived in America for nearly 40 years through my TV screen. I didn’t expect to feel so…different. Outside of my home country I don’t always know the code. What are suitable topics of conversation? Luckily we have Texan friends who will help us out and fortunately it’s usually fairly low-stakes. My daughter’s school explained that we needed a home-made post box in time for 14th February. Nonethless I didn’t realise every child in my son’s preschool class required a treat as well as a Valentine’s card. Next year we will try not to come off as the stingy Brits.

In the grand scheme of things these are minor issues. However, they serve to underline the scale of the challenge for other children who might be newly contending with language, literacy and sometimes the imprint of trauma. It’s a steep hill to climb. The very best thing we can offer in schools is empathy.

By Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Kate Grant

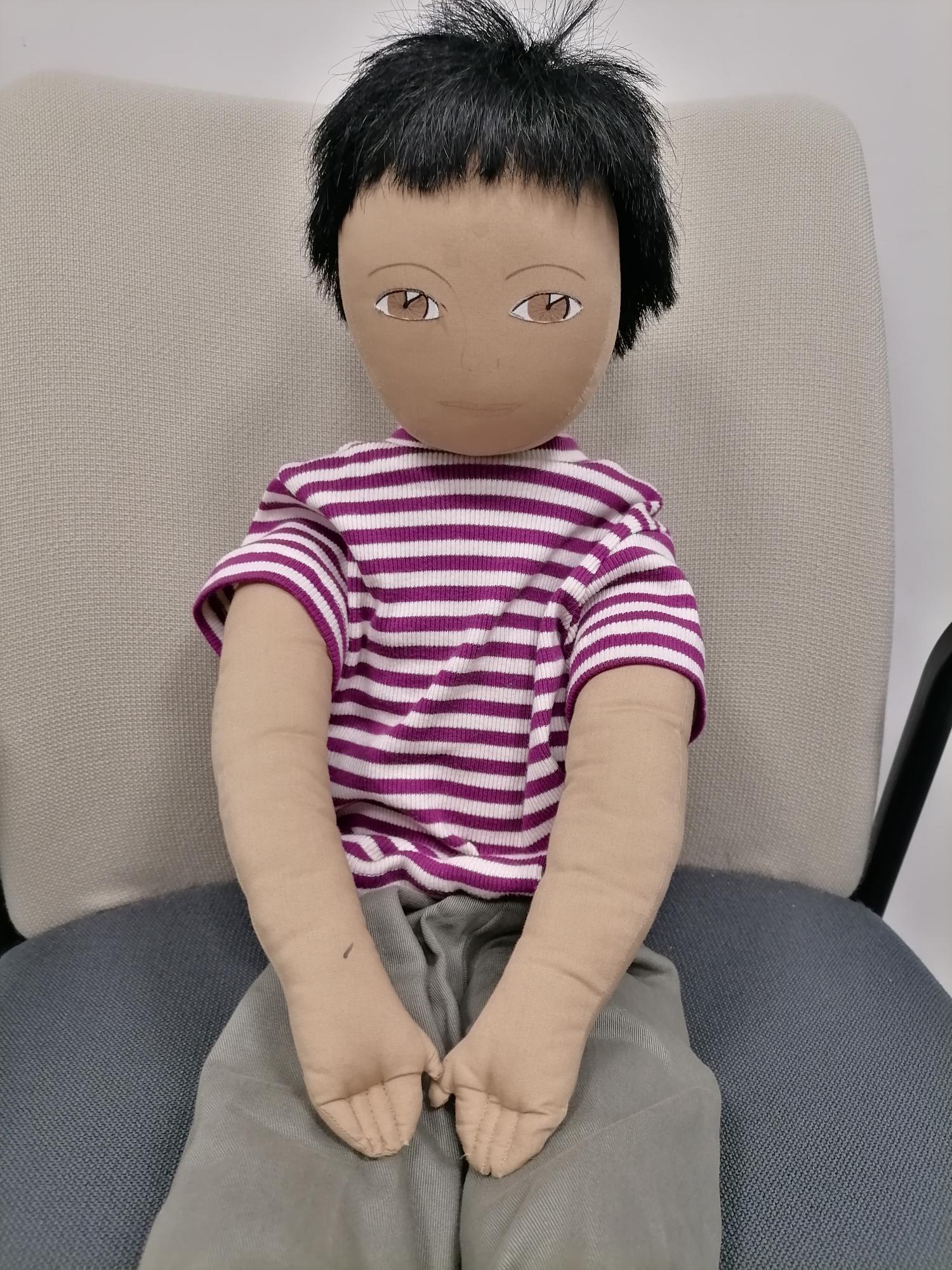

In this blog, Kate Grant interviews Albanian born Persona Doll Avdi. She asks how practitioners can work with EMTAS Persona Dolls to engage young learners with topics such as diversity, culture and stereotypes.

The Persona Dolls approach affords children an engaging, enjoyable and interactive safe space where they can address challenging issues, share their lived experiences and have their voices heard and valued. It helps our youngest learners to develop their emotional literacy and empowers children to use their voice. The approach is designed to facilitate dialogue around bias and stereotypes which so many of our youngest learners will have already encountered.

If you have used EMTAS Persona Dolls previously you will have noticed that they have been taking a well-deserved rest. After all, it’s not easy visiting lots of schools and making friends all over the county - just ask Avdi! Whilst the dolls have been relaxing, Kate has been working behind the scenes on making the use of EMTAS Persona Dolls in school more accessible, relevant and most of all fun. So without further ado please welcome Avdi to tell us more…

Avdi: Përshëndetje (hello) everyone, my name is Avdi and I am from Albania. Kate has asked me to share with you how working with Persona Dolls can help support your youngest learners in school. This is the perfect topic for me to talk about as I have been a Persona Doll my whole life!

Kate: What do you like about being a Persona Doll?

Avdi: One of the main things I love about being a Persona Doll is that I get to travel around the county, meeting lots of children and learning about different schools. I am always amazed by how warmly the children welcome me into their classroom - they sometimes even give me a school uniform to wear. But most of all, I love hearing the brilliant things children say when I go to visit their school and it often surprises their teachers too as we delve into conversations about issues they might not ordinarily get to discuss such as discrimination and inequality. Big topics for our youngest minds.

Kate: How do you support the children?

Avdi: I find that the children see me as being just like

them. This helps create a safe environment where they are happy to share and

talk about aspects of life they may not normally get to discuss. I think of it as providing children with a

window into someone else’s life, but they often find aspects that mirror their

own too. That’s what life is all about, learning

about yourself and others and embracing the similarities as well as the

differences.

Kate: How will teachers find time to use Persona Dolls?

Avdi: We work within the Early Years Foundation Stage and Key Stage 1/2 curriculum, so we are not an add-on. In fact we’re a different approach to teaching Personal, Social, Emotional Development, Knowledge and Understanding of The World and Relationships and Sex Education. Kate has linked all the relevant parts of the curriculum with our guidance documents so that teachers can see the objectives they can cover whilst working with us. For example you will see we provide an authentic way to approach the People, Culture and Communities element of the Early Years Foundation Stage curriculum [1] and the Respectful Relationships aspect of the Key Stage 1/2 curriculum [2].

Kate: What happens when you visit schools?

Avdi: I normally visit once a week for a half term. When I first go into a school, I explain that I am feeling a bit nervous about being somewhere new with people I don’t know yet, and the children discuss how they could help make me feel more comfortable. It’s lovely to hear how kind the children are and accepting of new people - I wish people were always like this. The next week when I return, I am more confident so I let their teacher share a PowerPoint I have made to tell them a bit more about myself, my home, my language and my interests. The children always want to tell me about themselves too and we find similarities and differences with each other.

By week 3 I am really enjoying being with my new group of friends and I share that something has been worrying me. For example, another child has been unkind to me because my hair is different to theirs. The teacher helps me talk to the children and they respond with so much empathy. A lot of the time, the children tell me they have experienced similar things and we talk about what helped them eg speaking to an adult at school. My new friends always give me good advice, so I go away and try some of their ideas. When I return for my final visit, I feel so much better because they supported me. I explain that I must return to my school again and might not see them, but we will still be friends. I like to surprise them with an e-postcard after my final visit. This shows I am still thinking of them and gives me an opportunity to ask them to write to me about our time together.

Kate: What is different about the way EMTAS Persona Dolls work now?

Avdi: Kate is working on making everything available online because we know how busy teachers are and we want everything to be readily accessible in the moment. Once everything is ready to go, it will all be uploaded to our Moodle where you will find the guidance documents, a list of all our Persona Dolls, suggestions for what to do during each visit and some social stories for teachers.

When I visit your school I will have a lanyard with a QR code so that teachers can find what they need instantly. When teachers share the Persona Doll’s PowerPoint it will contain video links to find out more about the culture and language(s) of the doll’s country of origin together with traditional dances and nursery rhymes in first language.

Kate: Is there anything else you want to tell everyone?

Avdi: Just that I am really excited to get back into schools and to meet lots of new friends. Oh, and if any schools would like to pilot our revamped way of working please email Kate at kate.grant@hants.gov.uk.

[1] Explain some similarities and differences between life in this country and life in other countries

[2] The importance of respecting others, even when they are very different from them (for example, physically, in character, personality or backgrounds), or make different choices or have different preferences or beliefs.

By Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisors Lisa Kalim and Astrid Dinneen

In the academic year 2021-22, Hampshire EMTAS saw its highest ever increase of referrals for asylum seekers and refugees with over 300 referrals made by schools. The majority were for children and young people from Afghanistan and Ukraine. The former was caused by the Taliban reclaiming power in Afghanistan in summer 2021 and the latter by the war in Ukraine starting in spring 2022.

In order to better support these children and families, Hampshire EMTAS welcomed new Bilingual Assistants on to the team covering Pashto, Dari, Farsi and Ukrainian languages. The Teacher Team caught up with these new colleagues to find out more about the backgrounds of these children. This highlighted many areas which school practitioners will find useful when settling and supporting their new arrivals. Lisa Kalim and Astrid Dinneen summarise these key areas before concluding with a list of recommendations and further resources.

Climate

In general, Afghanistan has extremely cold winters and hot summers, although there are regional variations. Most of the precipitation falls between December and April, with the summer months being very dry apart from in the south-eastern region. Afghan children may not consider our winters to be particularly cold or our summers particularly hot and may for example not feel the need to wear a coat in winter or short sleeves in summer.

In contrast, Ukraine has a temperate climate, with winters in the west being considerably milder than in the east. In summer, the east often has higher temperatures than the west. Summers are much wetter than winters with June and July being the wettest months. The west of Ukraine tends to have more rainfall than the east.

Geography

Afghanistan is a landlocked country in south-central Asia. It borders Pakistan to the east and south, Iran to the west, and the states of Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan to the north. It also has a short border with China in the extreme north-east. It covers an area more than twice the size of the UK. Afghanistan is divided into 34 provinces, each of which is sub-divided into 421 districts for administrative purposes. There are extensive mountainous areas, as well as high plateaus and plains. Mountains cover about three-quarters of the land area, with deserts in the south-west and north. The people of Afghanistan mainly live in rural areas in the fertile river valleys between the mountains, although the desert areas of the southwest are also becoming more populated. About 4.5 million people live in the capital, Kabul, in the east of the country.

Ukraine is located in eastern Europe and has borders with Belarus to the north, Russia to the east, Moldova and Romania to the south-west and Hungary, Slovakia and Poland to the west. In the south it has over 1,700 miles of coastline along the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea. It also covers an area more than twice the size of the UK but is slightly smaller than Afghanistan. Ukraine is a largely flat, relatively low-lying country consisting of plains with mountainous areas only in small areas near its southern and western borders. The majority of people live in urban areas in Ukraine with rural areas being much less densely populated. The east and west of the country have urban areas with higher populations, together with the cities of Kyiv in the north and Odessa in the south.

Languages

More than 30 languages are spoken in Afghanistan. Many Afghans are bilingual or multilingual. There are two official languages, Dari (also known as Farsi or Persian) and Pashto. Dari is more widely spoken than Pashto, with over 70% of the population speaking it either as a first or second language. It can be heard mainly in the central, northern, and western regions of the country. It is considered to be the language of trade, it is used by the government, its administration and mass media outlets. However, it is estimated that less than 50% of Dari speakers are literate. The primary ethnic groups that speak Dari as a first language include Tajiks, Hazaras, and Aymaqs.

Around 40% of the population are first language Pashto speakers, with a further 28% speaking it as an additional language. It can be heard predominantly in urban areas located in the south, southwest, and eastern parts of the country. Pashto is used for oral traditions such as storytelling as a high proportion of Pashto speakers are not literate in the language. Although spoken by people of various ethnic descents, Pashto is the native language of the Pashtuns, the majority ethnic group.

There are also five regional languages - Hazaragi, Uzbek, Turkmen, Balochi, and Pashayi. Hazaragi is a dialect of Dari. Additionally, there are around 30 other languages spoken by minority groups in Afghanistan including Pamiri, Arabic and Balochi.

There are at least 20 languages spoken in Ukraine. The most widely spoken is Ukrainian which is the country’s official language. Russian is spoken as a first language by approximately 30% of the population, mainly in the east near the border with Russia and in the south in Crimea. Generally, Russian speakers are more likely to live in cities, and are not found in large numbers in rural areas. Many first language Ukrainian speakers will also speak Russian as a second language. However, recently the Russian language has become a very sensitive issue for Ukrainians and now many Ukrainians do not want to use Russian at all. Other minority languages spoken in Ukraine include Romanian, Crimean Tatar, Bulgarian, Hungarian, Armenian, Belarusian and Romani.

School starting age

School starting age in both Afghanistan and Ukraine is much later than in the UK. Typically, Afghan children will start school at the age of 7. Many new arrivals into Hampshire will have attended school however many were not able to attend due to factors such as having to work to support their family, school being too far from their home, fears of terrorist attacks on schools, gender and of course COVID. As a result, the formal education of many children is fragmented or minimal. This can make it harder for these children to settle in school in the UK as many are not used to attending school regularly. When attending school in Afghanistan, children would attend half a day (about 3 ½ hours a day) hence attending a full school day in the UK would be very tiring for many new arrivals initially.

In Ukraine, parents will send their children to school between the age of 6 and 7. Until then, children will typically attend nursery where the curriculum is play based and where children still nap in the afternoon. This means that these children will find it hard to complete a full day in Year R and Year 1 due to tiredness as they are used to sleeping in the middle of the day. Additionally, it is common for children to go to bed much later than is usual in the UK ie between 22.00 and 23.00. This can also contribute to tiredness and settling in issues including behaviour problems. In primary school the academic part of the day usually finishes at around 1 pm and children attend clubs in the afternoon.

Attendance

In Afghanistan children may be accompanied to school by family members or neighbours in the early days of the academic year and they will usually walk to and from school without an adult for the rest of the year. Some children may choose not to attend and have a day out instead. Parents may not find out about their children missing school because absences are not routinely reported, particularly in state schools. In private schools however children have a home-school diary which supports communication between home and settings and any issues such as lateness, absences, lack of homework etc. are reported in writing.

In Ukraine, expectations around attendance are different from that in the UK. For example, children with a runny nose and a mild cough are considered by their families to be poorly hence they are kept away from settings for long periods of time eg a week or two. This tends to be encouraged by teachers in Ukraine. Similarly, parents in Ukraine will often take their children out of school to go on holiday or for an extended weekend away.

It may be necessary for school practitioners to have conversations with parents about expectations and the law around attendance in the UK and the requirement to let the school know if children are going to be absent.

School facilities

In both Afghanistan and Ukraine, facilities depend on whether schools are state or private and on whether they are located in a city or a remote village.

In Afghanistan, girls and boys are educated separately in state schools. However in private schools they are taught together. Class sizes in Afghanistan tend to be very large. Facilities in private schools may include buildings with classrooms and sometimes IT and Science equipment whereas in rural areas classes may take place outside as there may not be a building (it might not exist or may have been destroyed). State and private secondary schools are now closed for girls since the Taliban took over in Summer 2021.

In Ukraine there are also regional disparities affecting school facilities as well as differences between private and public sectors. Facilities eg interactive whiteboards may also depend on donations from families. Class sizes are similar to those in the UK.

Teaching and learning

In Afghanistan, children wear a uniform at school. Dari and Pashto are taught in both private and state schools together with Maths, Science, Geography, History and Art. English is taught from Year 4 in state schools and from Year 1 in private schools. IT is taught where facilities allow – sometimes through textbooks, sometimes through practical work. Since the Taliban came back to power there is more of a focus on religious studies than other subjects. Children in Afghanistan are usually taught from the front and are not expected to speak to each other or to work collaboratively, just copy from the board. When children deviate from this, corporal punishment is used to discipline them.

In Ukraine the range of subjects is similar to that offered in the UK. The language of instruction is Ukrainian across the whole country and most pupils, including Russian speakers, use Ukrainian for academic purposes. Russian is not taught in schools and is not part of the curriculum. Often even Russian speaking children are not literate in Russian. Younger children may know only the basics. Older children may be more confident with reading and writing in Russian however this is usually because they have taught themselves or learnt with their parents. Children do not wear a uniform. The teaching style in state schools is traditional with children being expected to sit passively and not move around the classroom. This means that new arrivals in the UK will have to adjust to a more active and collaborative approach to learning. In fact, newly arrived Ukrainian children sometimes report that they cannot distinguish the difference between lessons and break times in the UK.

In Ukraine pupils are used to receiving plenty of homework daily and families – usually mothers – tend to spend large amounts of time supporting their children with this every day. Outside of school families will commonly also employ private tutors. Families arriving in the UK have reported their surprise at how little homework their children receive in comparison. They also report not having a good grasp of how well their children are doing here because of the differences in grading work completed at school and at home. Homework is also very important in Afghanistan and children receive it daily.

In Ukraine, children would not be expected to play outside when it rains. In fact, settings should be aware that water play – even in the summer months – is not a well-accepted learning activity because the children may get wet. Similarly, sitting on the floor is not acceptable in Ukraine - particularly for girls.

In both Afghanistan and Ukraine children are required to pass assessments in order to progress to the next year group. In practice it is rare for Ukrainian children not to progress but it is relatively common in Afghanistan.

Extra-curricular activities

In Afghanistan children may attend private language centres to learn English outside of school. They may also attend taekwondo or karate clubs as well as private art courses. Some children work part-time to support their families however many families prefer to live modestly to be able to afford extra-curricular activities for their children. Football and cricket are very popular sports in Afghanistan.

Music schools are popular in Ukraine and it is usual for children to attend up to three times a week. Many children will have brought their musical instruments to the UK to continue practising. Sports such as athletics and gymnastics are also very popular and clubs are attended just as often. Children’s assiduity means their skills can surpass that of their UK peers. Settings should make every effort to find out about children’s interests and signpost ways for them to continue developing those skills in or outside of school.

SEND

Children with SEND do not usually attend school in Afghanistan, particularly in rural areas. Instead, it is likely that they would be kept at home. There is very little educational provision available in Afghanistan for children with SEND at present, but this is beginning to change. There are a few schools that specialise in children with SEND in the larger cities, but these are mostly private and so parents would need to be able to afford the fees for their children to attend. Kabul has the country’s only school for visually impaired children which is government funded and there are also schools for hearing impaired children in Kabul and Jalalabad. Additionally, there are other small schools in Kabul catering for children with a wide range of SEND, some of which do not charge fees as they are funded by charitable donations. For those children with SEND who are able to attend standard schools, no additional support is available. These children will not be able to progress to higher year groups if they fail the end of year exams and so may have to repeat a year several times. Many of these children will eventually drop out of school as a result.

In contrast with Afghanistan, children with SEND in Ukraine do usually attend school. In the past, these children were educated away from the mainstream in either special schools for those with SEND, including boarding schools, or in separate classes held in a mainstream school with no interaction with other children without SEND. However, although many children still attend segregated provision, Ukraine is now moving towards an inclusive approach where children with SEND are given the opportunity to attend mainstream schools. This means that many children with SEND now attend standard classes with their peers. Specialist centres conduct assessments of SEND and decide upon the most appropriate form of education for the child in consultation with the parents. Additional support is provided as needed, eg through the provision of Teaching Assistants.

In both Afghanistan and Ukraine SEND can be a sensitive subject for parents with some feeling a sense of stigma or shame around having a child with SEND. Therefore, it is important to be mindful of this possibility when discussing the subject of SEND with parents.

Relationship and Sex Education (RSE)

In Afghanistan children do not learn about sex and relationships at school. In Year 10, pupils may learn about anatomy and how babies are conceived as part of the Biology curriculum but this input excludes girls who do not attend secondary school. They learn about periods at home from their mothers, older sisters or friends and the quality of information is variable. Families may respond differently when informed about the RSE element of the school curriculum in the UK. Some may be happy for their children to receive well-informed advice at school whereas others are more reticent and may prefer to withdraw their children, especially in relation to the theme of same-sex relationships which are not permitted in Afghanistan. It is recommended that settings clarify the content of the RSE sessions and highlight themes such as healthy relationships with parents so they can make an informed decision based on the facts.

In Ukraine, subjects such as Health Education and Biology cover parts of sex education however relationships is not an area that is explored in detail and schools may not provide consistent guidance. Some families may not be comfortable discussing sex education with their children while others may try to do so using books and other resources.

Family and home life

Family is very important in both Ukraine and Afghanistan and it is common for children to live with their extended family, particularly their grandparents. They play a big part in the children’s lives. In fact, grandparents help so much at home that it has been noticed by UK Early Years settings that Ukrainian children can be less independent than their peers with routine tasks such as getting dressed or putting their shoes on. At the same time, it is also usual for Ukrainian parents to leave their young children alone at home to go to work and it can come as a surprise to them that in the UK parents are not expected to do this until children are much older. Similarly young children in Ukraine would usually go to the park or walk to school on their own hence it is useful for settings to be mindful and have conversations about this early on.

Families are also very close in Afghanistan. It is common for several families to live under the same roof and under the responsibility of the grandfather who is the decision-maker. Women are responsible for cleaning, cooking, and taking care of all the children. It’s not unusual for aunts and uncles to raise their nieces and nephews as their own children, which may explain why schools may welcome more than one ‘sibling’ within the same year group. To colleagues in the UK children may not strictly fall under our notion of brother or sister but for the children themselves the relationship is very strong indeed. Questions around children’s dates of birth should be asked sensitively and we must be reminded that not all will know their birth dates anyway.

For Afghan families who practise Islam the routine of the home revolves around prayer. Some families (Sunni Muslims in particular) pray 5 times a day while others (Shia Muslims) may pray 3 times a day. They wake up early for morning prayer. There is another prayer late in the evening after which families will have their dinner hence it is not unusual for children to go to bed late at around 23.00. In Ukraine, parents finish work at 18.00-19.00 to collect their children. Life starts then – families may go out and meet with friends. Children will also tend to go to bed late. Families moving to the UK from both Ukraine and Afghanistan have had to adjust to different routines and synchronise their body clocks to that of UK children who usually go to bed earlier and get up earlier too.

Food and diet is another area that families and children from Ukraine and Afghanistan have struggled with since moving to the UK. At the time of writing many families from Afghanistan are still housed in bridging hotels where they are unable to cook their own meals from fresh ingredients or at times of their choosing. Schools have also commented that many children are hungry during the day because they do not like school dinners. Instead they may bring in hard-boiled eggs and bread from the hotel breakfast buffet which is not always enough to sustain them until the end of a busy school day. In Ukraine, families will typically have a big breakfast consisting of waffles, omelettes, fruit, etc. and will usually have a late lunch consisting usually of soup followed by a main meal. Chips, pizzas and sandwiches and other foods offered at school are not considered a proper lunch.

To conclude this section on family life it is important to note that many refugee families coming to the UK have had to leave family members behind. For example, most Ukrainian children have moved here without their fathers and older brothers because they are required to fight for their country (there are some exceptions). Many Afghan children have also left members of their extended family behind and this can cause a lot of anxiety to those who are unsure about the safety of their loved ones. Families, including mothers who have moved to the UK with their children on their own, are having to cope without their usual support network. We must be reminded that for them juggling everything unaided for the first time can be stressful, particularly in a new country where systems, customs, education and much more are so unfamiliar.

Important dates

School settings should note important religious dates for which families may wish to withdraw their children (they have the right to 1 day for each festival). Schools may wish to take an interest and celebrate these dates through cards, assemblies, etc.

Afghanistan:

Independence day: 19th August

New Year’s day in Persian calendar: 21st March

Eid al-Adha: June 29th 2023

Ramadan: will start around March 23rd 2023 and last approximately 30 days

Eid al-Fitr: end of Ramadan, April 21st 2023

Further dates: Afghanistan Public Holidays 2023 - qppstudio.net

Ukraine:

7th January – Orthodox Christmas

Easter

Birthdays and name days

First Communion

Further dates: Upcoming Ukraine Public Holidays - qppstudio.net

Summing up - recommendations

Find out as much as you can about the background experiences of your new arrivals eg previous experience of school if any, literacy levels in home language(s), etc.

Use Google maps to find out where the children lived before moving to the UK. Did they live in a city or a rural area? Consider how this might have impacted access to services, education and other infrastructures. Consider also how this may have impacted their life experiences eg Afghan children will not be familiar with coasts and may for example need support to access stories and language relating to going to the beach and playing with a bucket and spade

Be aware that some Ukrainian parents may not be comfortable conversing in Russian, particularly to a person who is Russian rather than Ukrainian, even though they may be very competent in speaking Russian as a second language. Bear this in mind when planning to use an interpreter for meetings with parents – if a Ukrainian speaking interpreter is not available and you are considering using a Russian speaker instead always check with the family how they feel about using a Russian speaker before proceeding

Set up a home-school communication book to share details of topics covered at school. This helps families become aware of what their children are learning and is also an opportunity for them to discuss their learning at home in first language

Use ICTs to support communication with parents eg Google Translate, Microsoft Translator, DeepL Translate, SayHi, etc. Note some apps have audio features for some languages and not for others so check this in advance. For example, SayHi recognises speech in Ukrainian and Farsi but not in Pashto and Dari (these require the user to input text using an appropriate keyboard). When talking to parents also give a note written in English so they can get help from others to understand any key messages

Focus on pastoral care and support settling in initially

Discuss routines including bedtime

Clarify expectations regarding behaviour, attendance and punctuality

Explain what children should be able to do by themselves depending on their age eg getting dressed and what they should still be supported with eg walking to school

Be open-minded about children’s wider conception of what close family means

Provide ELSA and bereavement support where appropriate. Use interpreters where required

Talk to pupils about how they would like to observe their faith at school. Offer a space to pray

Provide Muslim children with a vegetarian or fish option. Ensure families understand that these meals are appropriate options for their children

Find out about children’s interests, skills and talents they may have developed in their country of origin eg art, sport, music, cooking, etc.

Clarify content of Relationship and Sex Education sessions

Be mindful that for some parents the subject of SEND can be sensitive

Attend training on how to best cater for the needs of refugee arrivals (see Hampshire EMTAS network meetings) https://www.hants.gov.uk/educationandlearning/emtas/training

Further reading and resources

Coming soon: more information about children speaking Pashto, Dari and Ukrainian will be added to our collection.

Many thanks to Olha Herhel, Kubra Behrooz and Sayed Kazimi for supporting the creation of this blog.

By Lynne Chinnery

In this three-part autobiographical blog, Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Lynne Chinnery takes us on a journey to Libya where she reminisces about the challenges and opportunities of moving to a country so drastically different to her own. In Part 1 and Part 2 we experienced Lynne's culture shock when she first arrived in Libya and read how she eventually found her place. In this final chapter Lynne focusses on her children and the decisions she had to make for the best of her family.

Part 3: Our children

We had made a conscious decision to bring our three children up bilingually from the very beginning as we could see the amazing benefits bilingualism could bring them. And so I mostly spoke to Sami, Leyla and Idris in English and my husband spoke to them in Arabic. As they spent more time with me when they were little, my husband would insist that they spoke to him in Arabic to ensure that they progressed in this language as much as in English. He did this in a playful way, pretending that he didn’t understand them whenever they spoke to him in English and they found this very funny as they knew that his English was really very good. They would use either language when talking to each other, often switching depending on who they were with, but there were some words that, as a family, we always tended to use only in one language or the other because they felt so much better in that language. For example, we’ve always referred to flip-flops or slippers as “shib-shib”, and shout “khalas” when we want someone to stop something. I’ve noticed many bilingual families do the same. Gaining Arabic literacy skills was not a problem, as all their lessons were in Arabic, and it was exciting but a bit daunting for me to see their writing in their school books in a language that I could barely read. I started teaching our children to read and write in English too as there was little of this taught at their schools. It took a lot of time and effort and I can understand why some parents baulk at the task, especially after a long day at work or school.

The Libyan people were warm and welcoming, many of my students became close friends, and I soon found that I regularly bumped into people in the city centre who I knew or who knew me through our school. I also found that the more my Arabic evolved, the happier I was, as I could ask for things in shops, joke with my neighbours and chat to the people in the doctor’s waiting room or on the bus. My children really helped with my Arabic acquisition as I could listen to them speaking Arabic to each other, and they also interpreted for me when I was stuck. I had made some English-speaking friends as well as my Libyan friends and we would meet on the nearby beach every morning during school holidays, which were wonderfully long. Our children would play and swim together while we chatted and shared food and drinks. It was particularly at times like these that our children seemed complete: running across the sand, climbing rocks and jumping into the clear Mediterranean Sea, code-switching from one language to another – half Libyan, half English but now, for these moments, whole.

Over the fourteen years that I lived in Benghazi, life grew easier. Of course there was some racism, as there is in every country. Some people slowed down in their cars to shout insults at me; some people talked about me rather than to me, thinking I couldn’t understand them; and some people were just hostile because I was a foreigner. But these were few compared to the warmth and generosity of the majority of the community; the friendships they offered assuaged the hurt I felt from any racism I experienced.

Our school flourished and we expanded the number of staff and classrooms. We moved from our small flat into a large, family villa with a surrounding garden that I loved to water at night. Gaddafi eased up on his restrictions on private shops and imports and so a much wider choice of groceries and products became available. Satellites arrived and although the government attempted to outlaw them, they were unsuccessful in doing so; the satellite dishes were being raised as fast as they could dismantle them. Eventually, they gave up and we could watch channels from many other countries, mostly Arab countries like Lebanon and Egypt, which had TV programmes and films in both English and Arabic. We were also finally able to watch world news via CNN and Al Jazeera, giving us a less censored version of current events. My husband and our children were happy watching TV in both languages, but I still craved English programmes as a way of switching off and relaxing in an Arabic world.

As time went on, however, it was actually the education in Libya that caused us the most trouble. By the time we had three children of school age, we found ourselves constantly trying to protect them from being beaten in school. We put them into private schools, which at least gave us the right to complain, but the system was still very old-fashioned: the classes were led by strict teachers who stood at their blackboards and dictated what should be copied down or memorised without any discussion. The pupils were sat in formal rows and if they stepped out of line or even answered incorrectly, a short piece of hose pipe or stick was used to hit them on their hands, and in extreme cases on their feet. I can still remember the fear we felt sending our children into such an environment; as well as the dread I felt when my husband was away and I had to go to the school unaccompanied, often to complain to the head about the corporal punishment being used. This would have been a difficult conversation to have in my first language, let alone in one I was still learning. In fact, I found it very stressful to attend any important meetings without someone there with me, even when my Arabic improved.

Eventually, as the political situation was not improving much and because of our growing concern about our children’s education, we decided that we would move back to the UK and put our children in English schools. The plan was that I would move first with the children and that we would visit Benghazi regularly, while my husband stayed on in Libya until he could get a job with a European airline. I had longed for this moment when I had first started living in Libya, but for a long time since, I had become accustomed to my life there: to our school, our home, our family and friends, my students (many of whom had become friends), and so I had stopped wishing that we could move to England. Now, although a part of me felt excited at the thought of moving back to the UK, another part of me felt that I had been away too long.

On my last trip to England, after a period of nearly four years without visiting, I had felt like a foreigner in the UK. It was a terrible realisation when it happened. I had thought that I still didn’t truly belong in Libya, but then upon visiting the UK, I realised to my horror that I didn’t belong there either. So much had happened while I was away, and this took me by surprise because in my head everything had stayed the same. Of course it would change, everything changes, but we don’t think of this when we are away, just as we don’t think about a child growing up and then we are surprised when we see that they are taller and older than before. But it wasn’t only this - I had changed. And so I suddenly had this awful realisation that I no longer belonged anywhere. I have spoken to other immigrants who have been through the same thing: that longing for home, then finding it so different once there that it no longer felt like home. It is a terrible feeling and one I will never forget. Feeling homeless. It does ease with time, and as I returned to Libya after that visit and continued my life there, I just felt that it was Libya which was becoming home to me more and more and I began to realise that I could see things differently to other people, neither one ‘side’ nor the other, a kind of insight into two worlds that are usually seen as poles apart.

So now, given the opportunity to move back to the UK, possibly for good, the thought of returning to live there was both exciting and frightening. Libya, in comparison, seemed safe – it was what I knew. I thought about it long and hard and decided it was right for us at that time and so we came. My husband visited us several times and we visited Libya too, but eventually he met someone else and we split up. I ensured that our children still kept in regular contact with him and they visited Libya at least once a year in the school holidays throughout their childhood.

Although the break-up of our family was a terrible time for all of us, I have never regretted my move back to the UK, especially in light of the terrible turmoil that has ensued there, just as I have never regretted my decision to move to Libya all those years ago. I learnt so much in Libya: the people taught me to understand other ways of living, of seeing, of understanding the world but they also revealed the similarities we all share: the love of family and friends and the hope for peace and security in our lives. They helped me to truly understand that people are people wherever you go and the majority of them are good.

Many thanks to Lynne Chinnery for sharing her personal story. Resources

for parents can be accessed from our website and on our Moodle.

Parents/carers who speak English as an Additional Language | Hampshire County Council (hants.gov.uk)

Advice for parents and carers (hants.gov.uk)

By Lynne Chinnery

In this three-part autobiographical blog, Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor, Lynne Chinnery, takes us on a journey to Libya where she reminisces about the challenges and opportunities of moving to a country so drastically different to her own. In Part 1 Lynne sets the scene and readers experience the culture shock she felt when she first arrived in Libya. In this second part we find out how she eventually found her place.

Sami, Leyla and Idris all dressed up for Eid

Part 2: Embracing the culture

After a year, I was pregnant with our first child, Sami, and as my husband didn’t want to leave, I felt I had no choice but to stay. I’m so glad I did.

Life soon settled into a fairly comfortable routine, with the main meal at lunchtime and a siesta afterwards if needed. Work and school were usually mornings only, six days a week but many people had two or more jobs to make ends meet. In the evenings, people stayed up late to make the most of the cooler night air. We sometimes went out to the lake for a walk in the gardens or stayed in and watched television. There were just two channels on Gaddafi’s strictly controlled TV in those days: one in Arabic and the other divided between French and English, mainly so that Gaddafi could spread the word of his Green Book and Socialist Jamahiriya theory. Most programmes were centred on his teachings and his take on the news, but there were some South American soap operas dubbed in Arabic that everyone crowded round to watch, as well as some ancient British sitcoms on the French/English channel for me. Tuning in to watch Terry and June whilst sat in a villa in the heart of Benghazi was a surreal experience, and I was surprised to find myself looking forward to each episode as there was little else I could understand, apart from rented videos and the BBC World Service on the radio.

Politically, Libya was a dictatorship under the complete control of Gaddafi, who was abhorred by the majority of its citizens (or at least that’s how I perceived it in Benghazi, where the resistance to the regime was strongest). But he had been in power so long and his rule was so harsh, that the majority of the population had learnt to live in a state of reluctant acceptance. For many, this was all they had known. Even my husband had been a child of just seven years when Gaddafi first took power from King Idris in a coup in 1969.

With my usual ability to pick the right time, the West had declared sanctions with Libya shortly after I arrived. Private enterprise had been slashed previously under Gaddafi’s vision of a Socialist state and, apart from a few shops selling cloth, which were still allowed to open in Soog AlJareed (a traditional market in the centre of Benghazi), the majority of shopping was done in the large government department stores or in the government Jamias. The department stores stood mostly empty but with one or two products in abundance, such as rows and rows of washing powder, endless lines of canned ghee, or shelves with just one type of skirt or sandals but very little else. The Jamias were local stores where we could buy necessities such as rice, oil and pasta - very important to a country with Italian heritage (Libya had been occupied by Italy from 1911 to 1943 and had retained some of its dishes, language and buildings). All items were modestly priced in the Jamia but rationed and you had to show your ration book in order to acquire them. Occasionally, we could also purchase some electrical goods such as a TV or a washing machine. If there weren’t enough for everybody, a lottery was held (although you still had to pay for the appliance if you won). Anything else people needed was bought on the black market, mostly from suitcase importers who travelled abroad to bring back what they could to sell. Not surprisingly, prices kept rising and the Libyan Dinar fell even further due to the sanctions, meaning that the cost of travelling abroad was particularly high and so I couldn’t visit home as often as planned.

I had been warned not to speak to anyone I didn’t know well about anything political – you could be locked up or even worse, and never to mention politics on the phone or in my letters home as these were all monitored. But with trusted family, friends and colleagues, we could speak freely and a closeness laced with black humour prevailed.

Sometimes there were flurries of physical resistance and I remember once stopping on the great bridge that spanned the largest of the lakes in central Benghazi, watching mortar bombs being fired into a block of flats. It sounds strange now, but we just stood there watching the whole scenario unfold before us as if we were watching a film. The residents had been evacuated because there were insurgents (the side we wanted to win) hiding within. I don’t think we ever found out what happened to them as such events were never reported in the news.

But on the whole, these were exceptions to our everyday life of family, school and work, interspersed with occasional picnics in the nearby countryside, trips to Jabal Al-Akthar Mountains (The Green Mountains) or days spent at one of the many breathtaking beaches. We now had three children: Sami, Leyla and Idris and so our thoughts were mostly preoccupied with acquiring the things we needed on the black market, getting our children ready for school on time, the successful growth of our language school and, for me, trying with great difficulty, to help my children with their Arabic homework and decipher the letters that came through the door when my husband was away.

There were some cultural aspects that I found more difficult to adjust to than others. For example, I just couldn’t understand why women and men had to sit in separate rooms unless they were family or close friends. This was especially painful at the beginning when I didn’t speak Arabic because if I was separated from my husband, I had no one to interpret for me. I also had to learn how short was too short for a skirt or dress, that trousers could only be worn with something long over the top, and that sleeveless tops were shameful. Libya had a real mix of orthodoxy at that time. Although the hijab was rarely worn, you could see women completely covered in a long-sleeved dress down to their ankles and a headscarf hiding their hair or, at the other extreme, you might see a young girl dressed in Western clothes driving by in her sportscar, her hair flying in the wind. Luckily for me, my husband’s family were somewhere in the middle, they were Muslim and believed in modest dress but were not insistent that anyone should wear a scarf, feeling that this was a personal choice.

The longer I stayed in Libya, the more ordinary the customs became to me. As my Arabic grew, I looked forward to the women’s get-togethers, known as ‘lemmas’, as a time to catch up with each other’s news and above all to laugh. I began to feel shy wearing my swimming costume on the beach and started wearing shorts over it as some of the Libyan women did and I wore a long shirt over my trousers when I went out. At home, I often wore a jalabiya: a long shift that was much cooler than jeans and a T-shirt. And I found that sitting on the floor to eat from shared bowls on a low table or tray was actually very sociable and relaxing, plus it certainly saved on the washing up! And all the time I was adjusting, my spoken Arabic was improving as I absorbed it from those around me. My literacy skills were also slowly coming along as I continued to teach myself from a book I had brought with me, and practised reading my children’s school books, frantically trying to keep up with them, but failing.

How did Lynne's family adjust to living in two languages? Come back next week to read the third and final part of her autobiographical blog.

By Lynne Chinnery

In this three-part autobiographical blog, Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor, Lynne Chinnery, takes us on a journey to Libya where she reminisces about the challenges and opportunities of moving to a country so drastically different to her own. Readers will reflect and empathise with the experiences of parents of international EAL arrivals settling in the UK.

View across the central lake of Benghazi, prior to the 2011 civil war

Part 1: The Culture Shock

Learning to live in a new country is never easy. The greater the differences that exist between the new language and culture and your own, the tougher it is. I only truly learnt this when I experienced it myself - by moving to Libya.

I had met my husband in Athens and we’d been together as much as possible for three years, during which time I was living in Greece, Turkey and London before moving to his home country of Libya. He was an airline pilot and I had trained as a primary school teacher, but most of my actual working experience had been in TEFL (Teaching English as a Foreign Language). After moving to Libya, I taught privately for a while before we jointly opened a language school on the northern coast of Libya, in his birthplace and our home, Benghazi.

When I first went to Libya, the dramatic change in culture, language, religious views, work, leisure, everything in fact, took me completely by surprise. Of course, I had known it would be different as I had lived abroad before, and it was the difference itself which I usually found so exciting and that inspired me to travel. But this was unlike anything I had ever experienced before; I had so much to learn that I felt bewildered and almost childlike. Part of the problem was my lack of Arabic and the fact that English was far less prevalent than in other countries I had visited; in fact, it had been banned in Libyan schools for some years.

With no understanding of Arabic, apart from a smattering of phrases I had taught myself prior to the move, I was still unable to do little more than greet people and say thank you and goodbye. I had learnt part of the alphabet, which meant I could pick out some letters on the otherwise unintelligible street signs, although even that was difficult as the fonts varied enormously and did not seem to look at all like the letters in my book. I fully understood for the first time how people who do not use the Latin script feel when they first travel to the UK: there was nothing familiar to hold onto.

As I descended from the air-conditioned plane, I was met with that blast of hot air which heat-seeking holiday makers are familiar with, and looking around me, everything was dry and flat, with only distant palm trees breaking up the landscape. As we drove from the airport to the city of Benghazi, however, following the sprawl of the city to its source, the dusty roads were gradually replaced with tarmac and I saw tall apartment blocks with splashes of colour from balconies full of potted plants, hanging rugs and washing. These in turn were soon replaced with villas, their lush gardens overflowing with palms, jasmine and bougainvillaea.

Benghazi had that chaotic mix of many towns and cities, where buildings have sprung up without any plan, a few even adopting part of the street as an extension of their garden. Small, modest houses, some in need of repair, shared the street with gigantic, newly-built villas, most sitting on untarmacked dusty roads that led away from the wide tarmacked road we were driving along. We passed parks with beautiful trees full of red blossoms and cherished, thick grass; interspersed with neglected areas of wasteland that had been left barren, with only dusty palms surviving in the ruddy, sandy soil. As we neared the city centre, modern municipal buildings interrupted more traditional houses and the streets were in the old Italian-style, dotted with shady plazas. At the heart of the city, a beautiful cathedral filled the skyline and the huge central lake of Benghazi stretched out before us. It really was stunning.

Of course, everybody had thought I was crazy to move to Libya, but I was in love with my husband and he talked about Libya in a way that was so different to its portrayal in the media that I had already begun to see it through his eyes. The reality was a shock for me: this time rather than working as an English teacher and living with English-speaking colleagues, I was immersed completely in the new culture. I had to deal with life in a shared house with my new mother-in-law and one of my sisters-in-law, neither of whom spoke English and I found this particularly stressful when my husband was away. Luckily, my other sister-in-law was a doctor and so was fluent in English. When you can’t express yourself in your first language, the relief you feel when someone comes into a room and chats with you in your mother tongue is incredible.

We lived in a beautiful old villa that had been left empty for some time, situated in an area close to the city centre. It belonged to a relative of my husband who had kindly loaned it to our family to use until our apartment was ready. Wide and spacious, with large airy rooms and a garden and veranda encircling it, the charm of our temporary home helped to make up for the fact that all washing water needed to be collected from the garden and drinking water drawn from a well on the outskirts of the city.

Other

differences I needed to get used to were not having a job to occupy me, the

shortage of available goods, a new and very different language to learn and on

top of all this, a multitude of baffling customs to contend with. I felt

overwhelmed, with nothing tangible or familiar to help me. I did think of

leaving; I nearly did leave. But I knew enough to realise that I was suffering

from culture shock more than anything else and agreed to try it for a year.

What will Lynne decide after spending a year in Libya? Come back next week to read Part 2.

By the Hampshire EMTAS Traveller Team

Due to current circumstances and the impact on schools of the lockdown, we have decided it would be a good idea to move our celebration of Gypsy, Roma, Traveller History Month (GRTHM) from its traditional month of June to October so no one will miss out on our planned events.

To this end, we are putting on three roadshows across the county. The roadshows will be in Basingstoke, Winchester and the New Forest and there will be something for everyone from talks to exhibitions to Stepping with FolkActive. The roadshows promise to be lively, entertaining and informative and will give our audiences a chance to see how Hampshire EMTAS works with its schools and GRT communities.

The roadshows are drop-in events with talks taking place between 4pm and 5pm after which people will be invited to take part in a stepping activity. Stepping is a traditional form of dance that was initially a type of sport for working class men in the north of England and for Travellers. Each dance is created by the individual dancer and does not follow any set rules – it is energetic and is often described as tapping or drumming with your feet. It requires no previous experience or expertise and when the live music is playing, it is impossible not to move your feet. Come along and join in.

There will also be an exhibition of the Life of Showmen displaying the rich history of Showmen in Hampshire through the decades and a display of all the entries to the a postcard competition (details below).

These promise to be lively events with lots of interaction, music and dance so save the date! The EMTAS Gypsy Roma Traveller History Month Roadshows will take place on:

1st October: The Discovery Centre, Winchester, 3.30 – 6.00pm

8th October: The Discovery Centre, Basingstoke, 3.30 – 6.00pm

22nd October: Applemore College, Hythe, 3.30 – 6.00pm

We hope lots of you will be able to attend a roadshow near you. We will soon be sending out a Schools Comm with further details and we’ll be advertising the roadshows on our website as well as issuing personal invitations to all the schools, families and agencies we work with. We look forward to welcoming you to one of these events and to getting to know you while you enjoy the exhibitions, talks and dancing. We hope to see you there!

The EMTAS GRTHM

postcard competition

As part of our GRTHM celebrations, we are also holding a postcard competition. It’s open to all GRT children and there are three categories: KS1, KS2 and KS3/4. We are launching the competition in June and need lots of support from our schools to make this a big success. The winning postcards are going to be printed and, in liaison with schools, sent to GRT children all over Hampshire in recognition for their improved attendance and/or attainment throughout the year. The winners in each category will also receive a prize and both winners and runners-up will see their postcards included in a full-colour calendar, something they can share with their families and feel really proud of. We will be in touch about the competition and how you can support your GRT children to take part in it very soon.

Meet the Hampshire EMTAS Traveller Team

The EMTAS Traveller Team consists of

Strategic Lead:

Sarah Coles (EMTAS Deputy Team Leader)

Operational Lead:

Claire Barker (Specialist Teacher Advisor)

EMTAS GRT Officer:

Sam Wilson (Attendance, Admissions and Transport)

Traveller Teaching Assistants:

Julie Curtis with responsibility for ELSA

Steve Clark

Our work always has an education focus and comprises working in partnership with schools to support Traveller children and families. At this time of year, we are heavily involved in transition work, supporting the move from infant to junior school for younger GRT children and from Year 6 to Year 7 for older ones. New for 2019-20 is our GRT Excellence Award, a self-evaluation framework that can support schools to develop and embed best practice in relation to their work with GRT communities. Also popular is our new GRT Reading Ambassador Scheme which is having a positive impact on children’s progress in reading in the pilot schools where it has been running. We can also support with attendance, admissions and transport applications and we can provide cultural awareness training to school staff.

Visit the Hampshire EMTAS website

Read our GRT blogs

Subscribe to our Blog Digest (select EMTAS)

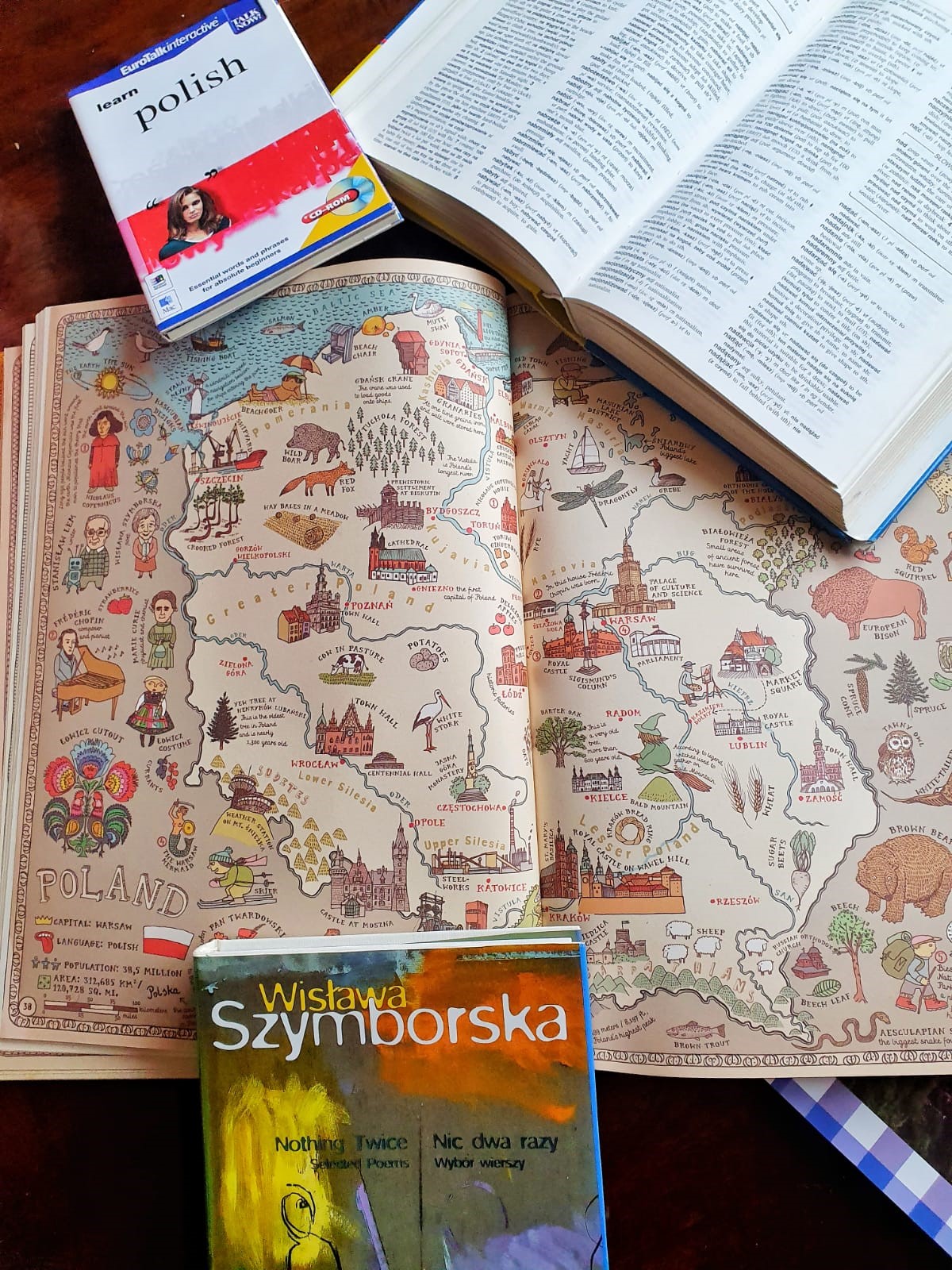

By Hampshire EMTAS Polish-speaking Bilingual Assistants Magdalena Raeburn and Katarzyna Tokarska.

Have you ever felt frustrated or out of your comfort zone because of communication barrier? Have you been on holiday abroad and found it tricky to explain what you need to your local shops, hotels or restaurants?

Imagine now, how much more complex and difficult a situation of an EAL child in a UK school might be. Try to put yourself in their shoes for a while… They come to the UK not for a holiday and not out of their own choice. They have to challenge themselves against a new language, new culture and a local community as well as the unknown school set of rules and regulations.

EMTAS Empathy Training will help you understand the complexity of the challenge that the EAL child faces every day. The aims of the session are:

- To increase awareness of the challenges that EAL learners face in the UK schools

- To give an insight into Polish learners’ cultural school differences

- To share ideas of how to approach the most common challenges experienced by the EAL learners.

During the training you will have a chance to become an EAL learner in a Polish classroom by taking part in a practical group activity on the geography of Poland. You will be expected to understand the teacher’s presentation, participate in a variety of activities, including group work, match the pictures, read and follow instructions as well as answer questions.

Would it be ‘only’ a language barrier…?

The training participants concluded that acquiring the language is only a part of the bigger picture. Cultural traits, local history, geography and customs are also a part of learning when they are trying to integrate into the new reality.

Our ‘students’ admitted that it ‘really made (them) consider other barriers than language’.

They also discovered that the manifested child’s behaviour in the classroom might have different roots rather than the ‘obvious’ ones… One of the participants said: ‘Very useful to understand how they would/could come across as ‘naughty’ or ‘distracted’’. It was an eye-opening experience.

Our workshop attendees revealed that their ‘survival’ strategy during the session was to answer ‘yes’ to any teacher’s attempt of communication. Have you got such EAL children in your classroom? Our workshop ‘students’ said it was their technique to use to be left alone rather than having to participate in the activity they do not feel competent or confident with. Our participants also felt ‘frustrated’, ‘confused’, ‘not very clever’ and ‘wanted to avoid being asked’. They were ‘easily disengaged’, ‘embarrassed when put on the spot’, ‘wanted to give up’ and ‘finally turned off’.

The session was an opportunity to face your own emotions as well as share the strategies, resources and ideas. Some strategies could involve researching information on the EAL child’s culture, educational system as well as taking your pupil’s personal experience into account.

When the EAL children join the UK classrooms, they need more than technicality of the language and pedagogical strategies. They need our empathy at every step of their challenging, new journey.

Take part in our empathy exercise at the Basingstoke EAL network meeting on January 28th. Limited spaces available and free to Hampshire maintained schools. For enquiries, please contact Lizzie Jenner, lizzie.jenner@hants.gov.uk.

Subscribe to our Blog Digest (select EMTAS).

Dawn Walters, Year R Team Leader at Hook Infant School, shares the exciting activities she planned as part of a Romany Gypsy Day she organised for her class.

Visit the Gypsy, Roma and Traveller (GRT) pages on the Hampshire EMTAS website.

Subscribe to the Blog Digest (select EMTAS).

By Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Claire Barker