Site blog

Anyone in the world

This blog is about a collaboration between Olha, an EMTAS Bilingual ELSA (B-ELSA) and Hannah, one of two school-based ELSAs at Fairview School. Working together, they provided emotional literacy support to Yehor, a child from Ukraine, when he was in Year 2 and again when he was in Year 3. In January 2025, EMTAS Team Leader Sarah Coles visited the school with Olha to talk to Yehor about his experience of that support.

Children from Ukraine in Hampshire schools

Most of Hampshire’s Ukrainian children came to the UK under the ‘Homes for Ukraine’ scheme following Russia’s full-scale invasion of their homeland in February 2022. As we’ve got to know them, we’ve learned they are linguists, mathematicians, musicians, physicists, dancers, artists, gymnasts, chess players and poets. And they are children who’ve been impacted by war, bringing with them experiences the like of which no child should have to endure. Some have had direct experience of the bombing raids, losing people, pets, homes and possessions that way; others have relatives and friends in the worst-affected regions of Ukraine and know about the impacts of the war through the experiences of those people; many continue to live apart from their male relatives who have stayed behind and are involved in the fighting, leading for some to further loss of loved ones as the war drags on. In short, it is not difficult to understand that some of our Ukrainian children may have a need for extra support as they learn to live with grief, separation and losses big and small - these experiences on top of the stress of getting used to living in a new country and a new language. Hence the creation of the B-ELSA role, one way in which Hampshire has responded to the support needs of children from Ukraine.

The B-ELSA role

EMTAS Ukrainian and Russian-speaking Bilingual Assistants have been ELSA-trained by Hampshire Educational Psychology (HEP) and they continue to receive the same supervision from HEP as school-based ELSAs. They are deployed to partner up with school ELSAs to plan and deliver ELSA sessions to children from Ukraine. Because of this collaborative approach, the child can access their ELSA sessions using any or all of their languages. While the B-ELSA moves from school to school throughout the working week, the school ELSA stays put. This ensures that the child has someone they can go to who understands their situation and is there for them all the time; they don’t have to wait for the next B-ELSA visit to get support. What the B-ELSA brings to the sessions is two-fold, both language and culture. Thus the B-ELSA can be a link with home for the child, bridging gaps between home and school in ways in which their school-based colleague cannot.

The school

Fairview School in south-west Hampshire is a one form entry primary school with around 240 children on roll. Most of the children are English-speaking and numbers of learners for whom English is an Additional Language are low at around 5%. The arrival of children from Ukraine has been a learning curve for everyone at Fairview, but people have been open to taking on this challenge and responding in ways that nurture a sense of belonging; the Ukrainian children are seen as bona fide members of this school’s community.

Meet Yehor

After the initial shock of joining the school in Year R, his first experience of being in an all-English environment, Yehor seems to settle in well. He tells me he is the youngest of three children and he talks about his dad, Stefan, and an uncle and aunt; these are the people in his family unit. Yehor likes Minecraft and stories. He plays football and he is partial to a custard cream. He doesn’t seem like a child who’s heard bombs falling on his home city, Kiev, or sat for hours in bomb shelters, waiting for the all-clear.

Yehor’s mother died when he was a baby so Stefan is parenting on his own alongside holding down a full-time job. The older siblings help out, collecting Yehor from school. Yehor says they sometimes call him the baby of the family; he doesn’t much like this.

Stefan is keen that his children maintain their language and culture and so when Yehor gets home, there is Ukrainian school work to be done too. Yehor is proud to be Ukrainian and keen to do well. He says

“If I do everything neatly, my dad will take photograph and send it to my teacher in Ukraine. My Ukrainian teacher says I am the best boy who write in Ukrainian.”

At Fairview, all is well until Year 2. By this time, Yehor is 7 and he’s been here two years. His English is developing well and he is able to access the learning, and is especially keen on maths. However, he begins to demonstrate some behaviours that tell staff he needs a different kind of support. When things don’t go his way, Yehor throws or breaks things, bangs his head on the table or retreats under it. If another child has something he wants, Yehor snatches it. If they get in his way, he roughly pushes them aside.

It is the school’s Head and Deputy who first suggest trying B-ELSA support, having heard about it at a district Head Teachers’ meeting. The school SENDCo agrees; she understands that these new behaviours might be Yehor’s attempt to communicate that he is struggling to navigate the bumpy terrain of living two very different lives, each with its own set of demands and expectations. One he lives at school in English and the other at home in Ukrainian – two different languages, two different cultures; small wonder he’s experiencing difficulties finding his way aged just 7 and with no route map to help him.

The B-ELSA-supported sessions

EMTAS B-ELSA Olha is the person in this story whose job it is to help Yehor build his own bridge so that he can navigate life in two languages and manage the emotional side of that experience. In her B-ELSA role, Olha says she sees herself as a facilitator, letting the school-based ELSA lead the sessions, ready to step in if a child seems hesitant, or if she sees there’s been a misunderstanding. School-based ELSA Hannah’s job is to provide continuity and to be the person who is there for Yehor every day, noticing when he’s coped well with a tricky situation and offering him an encouraging word, and feeding her day-to-day observations of him into session planning.

The two aims of Yehor’s B-ELSA-supported sessions are 1) to work on Yehor’s social skills and 2) to help him understand and name his own emotions – a vital step towards managing them for himself in more positive ways. In line with best practice for this way of working, at the start of each of Olha’s visits, and before Yehor joins them, Hannah briefs Olha on what’s been going on for Yehor between times. At the end, when Yehor’s gone back to class, they spend another few minutes reflecting on how the session went and planning for the next one.

After the second series of sessions in the autumn term of Yehor’s Year 3, the situation is much improved. Yehor is able to use lots of new words to talk about emotions – his own and those of others. He can identify when he is feeling angry and he describes ‘hot chocolate breathing’ as a strategy he’s learned in his B-ELSA-supported sessions and uses to calm himself down.

Yehor says the best part of his B-ELSA supported sessions has been the stories; he’s loved having Olha read to him in Ukrainian at the end. This has for Yehor been an affirmation of his Ukrainian identify, a link with his home language and his home country. It’s also been an opportunity for him to explore a new role, that of interpreter; he tells Hannah in English what the story’s about as they go, and he’s become really good at it, both Hannah and Olha affirm. Thus his sense of his own identity has been boosted and he has learned to accept praise where he’s achieved success, here as a young interpreter.

When asked if he’d recommend B-ELSA-supported sessions to other children from Ukraine, Yehor says “definitely,” adding that the sessions “…helped me a lot…to talk about how I’m feeling.” Now, when asked about school in England, Yehor tells me, “whole entire class is my friends.” He goes on, “I have to do everything correctly, listen, be good, be kind,” and he knows some ways to show those behaviours now, thanks to the sessions he’s had. And so we leave Yehor, a happy, settled, talkative boy who is now able to more fully enjoy the experience of growing up in more than one language.

___________________________________________________

For more information about children here as refugees, for

free resources and for specific information about accessing B-ELSA support for

a child from Ukraine, see the EMTAS Moodle Course: Asylum

Seeker & Refugee Support.

[ Modified: Monday, 10 March 2025, 9:50 AM ]

Anyone in the world

By Olha, EMTAS Bilingual ELSA and Sarah, ELSA at Shamblehurst Primary School

The Little Box of Big Thoughts from ‘Bear Us in Mind’

This blog explores how Bilingual ELSA (B-ELSA) support has worked at Shamblehurst Primary school in Hampshire. It brings together the perspectives of highly-experienced school-based ELSA Sarah, and EMTAS B-ELSA Olha. They collaborated to provide ELSA support to children from Ukraine. After an introductory section outlining why children from Ukraine might need ELSA support, the blog continues in the style of an interview, with questions followed by responses from these two practitioners.

Why B-ELSA support is particularly important for children from Ukraine

The need for this sort of support arises because of the array of challenging experiences many Ukrainian children will have had, related to their displacement from country of origin. For each Ukrainian child who has come to the UK as a refugee from war, their journey will be unique and may include things such as:

- sudden departure from Ukraine when the war started

- loss of their home in Ukraine

- loss of belongings

- separation from family members, who remain in Ukraine

- separation from friends

- leaving their pets behind

- not knowing for how long they will be in the UK

- adapting to living in someone else’s house with their rules and expectations (if with a host family in the UK)

- needing to adapt to life in a new language and culture

- loss of voice

- loss of choice

- loss of power and control over key aspects of their daily lives.

The

above examples all contribute to toxic stress, and come on top of other, more

common situational challenges that any child may experience, such as divorce or

changes in their family’s financial circumstances. Toxic stress can manifest itself in

physiological symptoms such as tummy aches or headaches, and in behaviours such

as withdrawal, regression to an earlier developmental stage or exerting control

through what appear to be acts of defiance or refusal, this strongly linked to the

child having lost their sense of self actualisation.

The EMTAS B-ELSA role was developed as a way of offering support with their emotional literacy to children from Ukraine, many of whom have an attendant language barrier to contend with on top of all the other worries and stresses they carry round with them daily. B-ELSAs work collaboratively with school-based ELSAs to plan, deliver and review ELSA sessions with children from Ukraine. The remainder of this blog draws on the experiences of Olha and Sarah who have successfully worked together to plan and deliver ELSA sessions to children from Ukraine.

How did you identify that your Ukrainian children needed ELSA support?

Sarah: Well, we noticed that there were things happening for the children at school that caused us to become concerned about them. Teachers were key in identifying that there may be a need in addition to learning English. This was discussed with our SENDCo and people on our Senior Leadership Team. Our Head Teacher played a role too and has been very supportive of the collaborative way of working that comes with B-ELSA involvement.

What have been the challenges in getting B-ELSA support to work?

Olha: In general, whilst I have dedicated slots in my calendar for this work, some schools have said they can’t release their ELSA to work with me, so that’s been a problem. Another issue I’ve had has been matching up calendars – mine and the school ELSA’s - to achieve consistency with the days and times of my visits. In this school, it’s been easy because the Head Teacher has been so supportive.

Sarah: To be perfectly honest, before I worked with Olha I did think in schools we are so busy so if she’s coming, it’s two adults to one child. I didn’t get it to start with - I thought ‘why don’t you just do the session on your own?’ But I totally get it now.

Olha: Yes, same here - on a personal level, when I first started B-ELSA work, I wasn’t convinced I needed to be there at all as some children from Ukraine didn’t seem to need me for the language support. I’ve changed my mind about that having had the experience of working with people like Sarah, and seeing how beneficial it is for the children.

Sarah: I think it was crucial you were here. You can give the children a real connection to home, because you give them opportunities to speak in first language. Each week, the children have looked to you for support to express particular things they’ve wanted to say; they’ve really benefited from that. Also the collaborative approach means when you stop coming, the child still has someone they know and can trust in school, someone who understands and is there for them.

How have you gone about collaboratively planning and delivering ELSA sessions?

Sarah: I’ve been really fortunate in that my school has been so open to B-ELSA support. I’ve been given two hours a week for our two Ukrainian children, which is an absolute gift; in my regular ELSA work I don’t usually get the luxury of planning time. Working with Olha, whilst I have suggested some possible activities for sessions, I’ve also valued her opinion and input. With the extra time, we’ve been able to plan sessions together, and we’ve shared our ideas.

Olha: Yes, so 15 mins ahead of the session with the child, we’ve met to recap on the previous session, and share and consider feedback from teachers about what happened for the child during the rest of the week between visits. It’s helped us tailor the sessions so we get them right for each child.

How have you figured out appropriate targets for the children you've worked with?

Sarah: One child had some friendship issues so we’ve done some work on that. They joined Year 5 and had to negotiate their place amongst friendships that were long-established within the peer group. For them, it’s been the social aspects that have been more immediately challenging, yet vital as they need to build a new support network for themselves and to gain a sense of belonging here in school.

Olha: Yes, and it’s been really helpful that Sarah knows the other children in the class. She’s brought that knowledge to the sessions – I wouldn’t have been able to do that bit on my own. For this child, we’ve also worked on boundaries, the need to respect others’ feelings, what we can do for ourselves when we’re feeling upset. So lots of work on emotional literacy.

Sarah: For another child, we decided we’d work on social skills as they’d been having difficulties following instructions in class. We introduced a second child and we played some games together. We talked about the rules of those games. The Ukrainian child said they wanted to make a booklet so we came up with the idea of making a book of rules – things we need to remember when we’re playing with friends. Each week we played a different game and we talked about the rules.

Olha: Yes, they knew we were working on that book, which was their idea. At the end, they were so proud of their book of rules and they took it to share with their class. I believe this child was more focused and engaged because we followed that project with them, their own idea.

How did you draw on the child's first language in your sessions?

Olha: I’ve collected resources in Ukrainian, Russian and English through this role. Some have come from my ELSA training with the Educational Psychology service; I especially like the ones from ‘Bear us in Mind’ – which is a charity set up to support refugee children, including those from Ukraine.

Sarah: We wanted to make sure the children understood the feelings words we were using. We used cards to talk about that. The children definitely needed Olha to be able to do this effectively. Also, after seeing some of the resources in Ukrainian that Olha brought with her, I started using translation tools myself, to create more.

For me, the language options Olha’s opened up for the children is the beauty of it – we’ll come in and have a chat about each child and go in my ELSA cupboard and choose something suitable. For example the feelings cards – we picked a few cards and we asked what’s happening in the picture. If we could add a speech bubble to the picture, what would they be saying/thinking? Because Olha’s been there, the children have been able to use whichever language they like to express their thoughts and ideas. I think this has been a real strength of it.

What has been the hardest part of working in this way?

Sarah: To be honest, at the beginning I was concerned about my waiting list children. I have lots of children with lots of needs. Prioritising the Ukrainian children did make me feel a bit bad. But a child at the top of my list was the one we chose to join some of the B-ELSA-supported sessions, which was great, really fortunate that it worked out that way.

Also, the targets from the teachers needed a bit of work to get them right for the children.

Olha: We agreed on that – it’s been really common in my experience in this role. Teachers sometimes think we have a magic wand and can solve anything and everything, but ELSA support can really only help with one thing at a time.

Sarah: Yes, when we had our Remembrance Day, one child suddenly started talking about everything they’d been through and the teachers and the other children were shocked to hear it. I think when something like that happens, people can go into panic mode.

Olha: I think this is sometimes where it doesn’t work so well in other schools – people lose confidence. They sit back and they seem to want me to do everything, which isn’t how it’s meant to work.

What's been the most useful thing to have come out of your collaboration?

Sarah: The legacy – through the work we’ve done together, the children have accessed the ELSA sessions so they’ve benefited from that. Plus now they know me really well, and they understand I’m always here for them, even if Olha’s visits have ended for the time being.

How do you achieve a sense of closure at the end of a period of ELSA support?

Sarah: Closure was really important for the children. In the end, we decided we’d give each child a card, so I modified one I had. In it, we put that Olha’s saying goodbye but the child can still come and talk to me.

Olha: Yes, a card like

this is a resource we’re now developing at EMTAS. The new cards will be printed with space to

add something personal, special to each child. All the EMTAS B-ELSAs will be able to give

them to the children they’ve worked with.

The

above conversation outlines some of the challenges associated with accessing

B-ELSA support for children from Ukraine and some of the benefits – for the

children, for their peers and for the adults around them. It illustrates how one school has added B-ELSA

support to their work with Ukrainian children and their families, developing a

healing environment in which the children can begin to recover from the trauma

they’ve experienced. To find out more

about working with refugee children and to access various free resources,

including ‘Bear us in Mind’, mentioned by Olha, see Course: Asylum

Seeker & Refugee Support (hants.gov.uk).

[ Modified: Wednesday, 17 April 2024, 10:24 AM ]

Anyone in the world

By Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisors Lisa Kalim and Astrid Dinneen

In the academic year 2021-22, Hampshire EMTAS saw its highest ever increase of referrals for asylum seekers and refugees with over 300 referrals made by schools. The majority were for children and young people from Afghanistan and Ukraine. The former was caused by the Taliban reclaiming power in Afghanistan in summer 2021 and the latter by the war in Ukraine starting in spring 2022.

In order to better support these children and families, Hampshire EMTAS welcomed new Bilingual Assistants on to the team covering Pashto, Dari, Farsi and Ukrainian languages. The Teacher Team caught up with these new colleagues to find out more about the backgrounds of these children. This highlighted many areas which school practitioners will find useful when settling and supporting their new arrivals. Lisa Kalim and Astrid Dinneen summarise these key areas before concluding with a list of recommendations and further resources.

Climate

In general, Afghanistan has extremely cold winters and hot summers, although there are regional variations. Most of the precipitation falls between December and April, with the summer months being very dry apart from in the south-eastern region. Afghan children may not consider our winters to be particularly cold or our summers particularly hot and may for example not feel the need to wear a coat in winter or short sleeves in summer.

In contrast, Ukraine has a temperate climate, with winters in the west being considerably milder than in the east. In summer, the east often has higher temperatures than the west. Summers are much wetter than winters with June and July being the wettest months. The west of Ukraine tends to have more rainfall than the east.

Geography

Afghanistan is a landlocked country in south-central Asia. It borders Pakistan to the east and south, Iran to the west, and the states of Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan to the north. It also has a short border with China in the extreme north-east. It covers an area more than twice the size of the UK. Afghanistan is divided into 34 provinces, each of which is sub-divided into 421 districts for administrative purposes. There are extensive mountainous areas, as well as high plateaus and plains. Mountains cover about three-quarters of the land area, with deserts in the south-west and north. The people of Afghanistan mainly live in rural areas in the fertile river valleys between the mountains, although the desert areas of the southwest are also becoming more populated. About 4.5 million people live in the capital, Kabul, in the east of the country.

Ukraine is located in eastern Europe and has borders with Belarus to the north, Russia to the east, Moldova and Romania to the south-west and Hungary, Slovakia and Poland to the west. In the south it has over 1,700 miles of coastline along the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea. It also covers an area more than twice the size of the UK but is slightly smaller than Afghanistan. Ukraine is a largely flat, relatively low-lying country consisting of plains with mountainous areas only in small areas near its southern and western borders. The majority of people live in urban areas in Ukraine with rural areas being much less densely populated. The east and west of the country have urban areas with higher populations, together with the cities of Kyiv in the north and Odessa in the south.

Languages

More than 30 languages are spoken in Afghanistan. Many Afghans are bilingual or multilingual. There are two official languages, Dari (also known as Farsi or Persian) and Pashto. Dari is more widely spoken than Pashto, with over 70% of the population speaking it either as a first or second language. It can be heard mainly in the central, northern, and western regions of the country. It is considered to be the language of trade, it is used by the government, its administration and mass media outlets. However, it is estimated that less than 50% of Dari speakers are literate. The primary ethnic groups that speak Dari as a first language include Tajiks, Hazaras, and Aymaqs.

Around 40% of the population are first language Pashto speakers, with a further 28% speaking it as an additional language. It can be heard predominantly in urban areas located in the south, southwest, and eastern parts of the country. Pashto is used for oral traditions such as storytelling as a high proportion of Pashto speakers are not literate in the language. Although spoken by people of various ethnic descents, Pashto is the native language of the Pashtuns, the majority ethnic group.

There are also five regional languages - Hazaragi, Uzbek, Turkmen, Balochi, and Pashayi. Hazaragi is a dialect of Dari. Additionally, there are around 30 other languages spoken by minority groups in Afghanistan including Pamiri, Arabic and Balochi.

There are at least 20 languages spoken in Ukraine. The most widely spoken is Ukrainian which is the country’s official language. Russian is spoken as a first language by approximately 30% of the population, mainly in the east near the border with Russia and in the south in Crimea. Generally, Russian speakers are more likely to live in cities, and are not found in large numbers in rural areas. Many first language Ukrainian speakers will also speak Russian as a second language. However, recently the Russian language has become a very sensitive issue for Ukrainians and now many Ukrainians do not want to use Russian at all. Other minority languages spoken in Ukraine include Romanian, Crimean Tatar, Bulgarian, Hungarian, Armenian, Belarusian and Romani.

School starting age

School starting age in both Afghanistan and Ukraine is much later than in the UK. Typically, Afghan children will start school at the age of 7. Many new arrivals into Hampshire will have attended school however many were not able to attend due to factors such as having to work to support their family, school being too far from their home, fears of terrorist attacks on schools, gender and of course COVID. As a result, the formal education of many children is fragmented or minimal. This can make it harder for these children to settle in school in the UK as many are not used to attending school regularly. When attending school in Afghanistan, children would attend half a day (about 3 ½ hours a day) hence attending a full school day in the UK would be very tiring for many new arrivals initially.

In Ukraine, parents will send their children to school between the age of 6 and 7. Until then, children will typically attend nursery where the curriculum is play based and where children still nap in the afternoon. This means that these children will find it hard to complete a full day in Year R and Year 1 due to tiredness as they are used to sleeping in the middle of the day. Additionally, it is common for children to go to bed much later than is usual in the UK ie between 22.00 and 23.00. This can also contribute to tiredness and settling in issues including behaviour problems. In primary school the academic part of the day usually finishes at around 1 pm and children attend clubs in the afternoon.

Attendance

In Afghanistan children may be accompanied to school by family members or neighbours in the early days of the academic year and they will usually walk to and from school without an adult for the rest of the year. Some children may choose not to attend and have a day out instead. Parents may not find out about their children missing school because absences are not routinely reported, particularly in state schools. In private schools however children have a home-school diary which supports communication between home and settings and any issues such as lateness, absences, lack of homework etc. are reported in writing.

In Ukraine, expectations around attendance are different from that in the UK. For example, children with a runny nose and a mild cough are considered by their families to be poorly hence they are kept away from settings for long periods of time eg a week or two. This tends to be encouraged by teachers in Ukraine. Similarly, parents in Ukraine will often take their children out of school to go on holiday or for an extended weekend away.

It may be necessary for school practitioners to have conversations with parents about expectations and the law around attendance in the UK and the requirement to let the school know if children are going to be absent.

School facilities

In both Afghanistan and Ukraine, facilities depend on whether schools are state or private and on whether they are located in a city or a remote village.

In Afghanistan, girls and boys are educated separately in state schools. However in private schools they are taught together. Class sizes in Afghanistan tend to be very large. Facilities in private schools may include buildings with classrooms and sometimes IT and Science equipment whereas in rural areas classes may take place outside as there may not be a building (it might not exist or may have been destroyed). State and private secondary schools are now closed for girls since the Taliban took over in Summer 2021.

In Ukraine there are also regional disparities affecting school facilities as well as differences between private and public sectors. Facilities eg interactive whiteboards may also depend on donations from families. Class sizes are similar to those in the UK.

Teaching and learning

In Afghanistan, children wear a uniform at school. Dari and Pashto are taught in both private and state schools together with Maths, Science, Geography, History and Art. English is taught from Year 4 in state schools and from Year 1 in private schools. IT is taught where facilities allow – sometimes through textbooks, sometimes through practical work. Since the Taliban came back to power there is more of a focus on religious studies than other subjects. Children in Afghanistan are usually taught from the front and are not expected to speak to each other or to work collaboratively, just copy from the board. When children deviate from this, corporal punishment is used to discipline them.

In Ukraine the range of subjects is similar to that offered in the UK. The language of instruction is Ukrainian across the whole country and most pupils, including Russian speakers, use Ukrainian for academic purposes. Russian is not taught in schools and is not part of the curriculum. Often even Russian speaking children are not literate in Russian. Younger children may know only the basics. Older children may be more confident with reading and writing in Russian however this is usually because they have taught themselves or learnt with their parents. Children do not wear a uniform. The teaching style in state schools is traditional with children being expected to sit passively and not move around the classroom. This means that new arrivals in the UK will have to adjust to a more active and collaborative approach to learning. In fact, newly arrived Ukrainian children sometimes report that they cannot distinguish the difference between lessons and break times in the UK.

In Ukraine pupils are used to receiving plenty of homework daily and families – usually mothers – tend to spend large amounts of time supporting their children with this every day. Outside of school families will commonly also employ private tutors. Families arriving in the UK have reported their surprise at how little homework their children receive in comparison. They also report not having a good grasp of how well their children are doing here because of the differences in grading work completed at school and at home. Homework is also very important in Afghanistan and children receive it daily.

In Ukraine, children would not be expected to play outside when it rains. In fact, settings should be aware that water play – even in the summer months – is not a well-accepted learning activity because the children may get wet. Similarly, sitting on the floor is not acceptable in Ukraine - particularly for girls.

In both Afghanistan and Ukraine children are required to pass assessments in order to progress to the next year group. In practice it is rare for Ukrainian children not to progress but it is relatively common in Afghanistan.

Extra-curricular activities

In Afghanistan children may attend private language centres to learn English outside of school. They may also attend taekwondo or karate clubs as well as private art courses. Some children work part-time to support their families however many families prefer to live modestly to be able to afford extra-curricular activities for their children. Football and cricket are very popular sports in Afghanistan.

Music schools are popular in Ukraine and it is usual for children to attend up to three times a week. Many children will have brought their musical instruments to the UK to continue practising. Sports such as athletics and gymnastics are also very popular and clubs are attended just as often. Children’s assiduity means their skills can surpass that of their UK peers. Settings should make every effort to find out about children’s interests and signpost ways for them to continue developing those skills in or outside of school.

SEND

Children with SEND do not usually attend school in Afghanistan, particularly in rural areas. Instead, it is likely that they would be kept at home. There is very little educational provision available in Afghanistan for children with SEND at present, but this is beginning to change. There are a few schools that specialise in children with SEND in the larger cities, but these are mostly private and so parents would need to be able to afford the fees for their children to attend. Kabul has the country’s only school for visually impaired children which is government funded and there are also schools for hearing impaired children in Kabul and Jalalabad. Additionally, there are other small schools in Kabul catering for children with a wide range of SEND, some of which do not charge fees as they are funded by charitable donations. For those children with SEND who are able to attend standard schools, no additional support is available. These children will not be able to progress to higher year groups if they fail the end of year exams and so may have to repeat a year several times. Many of these children will eventually drop out of school as a result.

In contrast with Afghanistan, children with SEND in Ukraine do usually attend school. In the past, these children were educated away from the mainstream in either special schools for those with SEND, including boarding schools, or in separate classes held in a mainstream school with no interaction with other children without SEND. However, although many children still attend segregated provision, Ukraine is now moving towards an inclusive approach where children with SEND are given the opportunity to attend mainstream schools. This means that many children with SEND now attend standard classes with their peers. Specialist centres conduct assessments of SEND and decide upon the most appropriate form of education for the child in consultation with the parents. Additional support is provided as needed, eg through the provision of Teaching Assistants.

In both Afghanistan and Ukraine SEND can be a sensitive subject for parents with some feeling a sense of stigma or shame around having a child with SEND. Therefore, it is important to be mindful of this possibility when discussing the subject of SEND with parents.

Relationship and Sex Education (RSE)

In Afghanistan children do not learn about sex and relationships at school. In Year 10, pupils may learn about anatomy and how babies are conceived as part of the Biology curriculum but this input excludes girls who do not attend secondary school. They learn about periods at home from their mothers, older sisters or friends and the quality of information is variable. Families may respond differently when informed about the RSE element of the school curriculum in the UK. Some may be happy for their children to receive well-informed advice at school whereas others are more reticent and may prefer to withdraw their children, especially in relation to the theme of same-sex relationships which are not permitted in Afghanistan. It is recommended that settings clarify the content of the RSE sessions and highlight themes such as healthy relationships with parents so they can make an informed decision based on the facts.

In Ukraine, subjects such as Health Education and Biology cover parts of sex education however relationships is not an area that is explored in detail and schools may not provide consistent guidance. Some families may not be comfortable discussing sex education with their children while others may try to do so using books and other resources.

Family and home life

Family is very important in both Ukraine and Afghanistan and it is common for children to live with their extended family, particularly their grandparents. They play a big part in the children’s lives. In fact, grandparents help so much at home that it has been noticed by UK Early Years settings that Ukrainian children can be less independent than their peers with routine tasks such as getting dressed or putting their shoes on. At the same time, it is also usual for Ukrainian parents to leave their young children alone at home to go to work and it can come as a surprise to them that in the UK parents are not expected to do this until children are much older. Similarly young children in Ukraine would usually go to the park or walk to school on their own hence it is useful for settings to be mindful and have conversations about this early on.

Families are also very close in Afghanistan. It is common for several families to live under the same roof and under the responsibility of the grandfather who is the decision-maker. Women are responsible for cleaning, cooking, and taking care of all the children. It’s not unusual for aunts and uncles to raise their nieces and nephews as their own children, which may explain why schools may welcome more than one ‘sibling’ within the same year group. To colleagues in the UK children may not strictly fall under our notion of brother or sister but for the children themselves the relationship is very strong indeed. Questions around children’s dates of birth should be asked sensitively and we must be reminded that not all will know their birth dates anyway.

For Afghan families who practise Islam the routine of the home revolves around prayer. Some families (Sunni Muslims in particular) pray 5 times a day while others (Shia Muslims) may pray 3 times a day. They wake up early for morning prayer. There is another prayer late in the evening after which families will have their dinner hence it is not unusual for children to go to bed late at around 23.00. In Ukraine, parents finish work at 18.00-19.00 to collect their children. Life starts then – families may go out and meet with friends. Children will also tend to go to bed late. Families moving to the UK from both Ukraine and Afghanistan have had to adjust to different routines and synchronise their body clocks to that of UK children who usually go to bed earlier and get up earlier too.

Food and diet is another area that families and children from Ukraine and Afghanistan have struggled with since moving to the UK. At the time of writing many families from Afghanistan are still housed in bridging hotels where they are unable to cook their own meals from fresh ingredients or at times of their choosing. Schools have also commented that many children are hungry during the day because they do not like school dinners. Instead they may bring in hard-boiled eggs and bread from the hotel breakfast buffet which is not always enough to sustain them until the end of a busy school day. In Ukraine, families will typically have a big breakfast consisting of waffles, omelettes, fruit, etc. and will usually have a late lunch consisting usually of soup followed by a main meal. Chips, pizzas and sandwiches and other foods offered at school are not considered a proper lunch.

To conclude this section on family life it is important to note that many refugee families coming to the UK have had to leave family members behind. For example, most Ukrainian children have moved here without their fathers and older brothers because they are required to fight for their country (there are some exceptions). Many Afghan children have also left members of their extended family behind and this can cause a lot of anxiety to those who are unsure about the safety of their loved ones. Families, including mothers who have moved to the UK with their children on their own, are having to cope without their usual support network. We must be reminded that for them juggling everything unaided for the first time can be stressful, particularly in a new country where systems, customs, education and much more are so unfamiliar.

Important dates

School settings should note important religious dates for which families may wish to withdraw their children (they have the right to 1 day for each festival). Schools may wish to take an interest and celebrate these dates through cards, assemblies, etc.

Afghanistan:

Independence day: 19th August

New Year’s day in Persian calendar: 21st March

Eid al-Adha: June 29th 2023

Ramadan: will start around March 23rd 2023 and last approximately 30 days

Eid al-Fitr: end of Ramadan, April 21st 2023

Further dates: Afghanistan Public Holidays 2023 - qppstudio.net

Ukraine:

7th January – Orthodox Christmas

Easter

Birthdays and name days

First Communion

Further dates: Upcoming Ukraine Public Holidays - qppstudio.net

Summing up - recommendations

Find out as much as you can about the background experiences of your new arrivals eg previous experience of school if any, literacy levels in home language(s), etc.

Use Google maps to find out where the children lived before moving to the UK. Did they live in a city or a rural area? Consider how this might have impacted access to services, education and other infrastructures. Consider also how this may have impacted their life experiences eg Afghan children will not be familiar with coasts and may for example need support to access stories and language relating to going to the beach and playing with a bucket and spade

Be aware that some Ukrainian parents may not be comfortable conversing in Russian, particularly to a person who is Russian rather than Ukrainian, even though they may be very competent in speaking Russian as a second language. Bear this in mind when planning to use an interpreter for meetings with parents – if a Ukrainian speaking interpreter is not available and you are considering using a Russian speaker instead always check with the family how they feel about using a Russian speaker before proceeding

Set up a home-school communication book to share details of topics covered at school. This helps families become aware of what their children are learning and is also an opportunity for them to discuss their learning at home in first language

Use ICTs to support communication with parents eg Google Translate, Microsoft Translator, DeepL Translate, SayHi, etc. Note some apps have audio features for some languages and not for others so check this in advance. For example, SayHi recognises speech in Ukrainian and Farsi but not in Pashto and Dari (these require the user to input text using an appropriate keyboard). When talking to parents also give a note written in English so they can get help from others to understand any key messages

Focus on pastoral care and support settling in initially

Discuss routines including bedtime

Clarify expectations regarding behaviour, attendance and punctuality

Explain what children should be able to do by themselves depending on their age eg getting dressed and what they should still be supported with eg walking to school

Be open-minded about children’s wider conception of what close family means

Provide ELSA and bereavement support where appropriate. Use interpreters where required

Talk to pupils about how they would like to observe their faith at school. Offer a space to pray

Provide Muslim children with a vegetarian or fish option. Ensure families understand that these meals are appropriate options for their children

Find out about children’s interests, skills and talents they may have developed in their country of origin eg art, sport, music, cooking, etc.

Clarify content of Relationship and Sex Education sessions

Be mindful that for some parents the subject of SEND can be sensitive

Attend training on how to best cater for the needs of refugee arrivals (see Hampshire EMTAS network meetings) https://www.hants.gov.uk/educationandlearning/emtas/training

Further reading and resources

Coming soon: more information about children speaking Pashto, Dari and Ukrainian will be added to our collection.

Many thanks to Olha Herhel, Kubra Behrooz and Sayed Kazimi for supporting the creation of this blog.

[ Modified: Thursday, 24 November 2022, 9:05 AM ]

Anyone in the world

By the Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisors

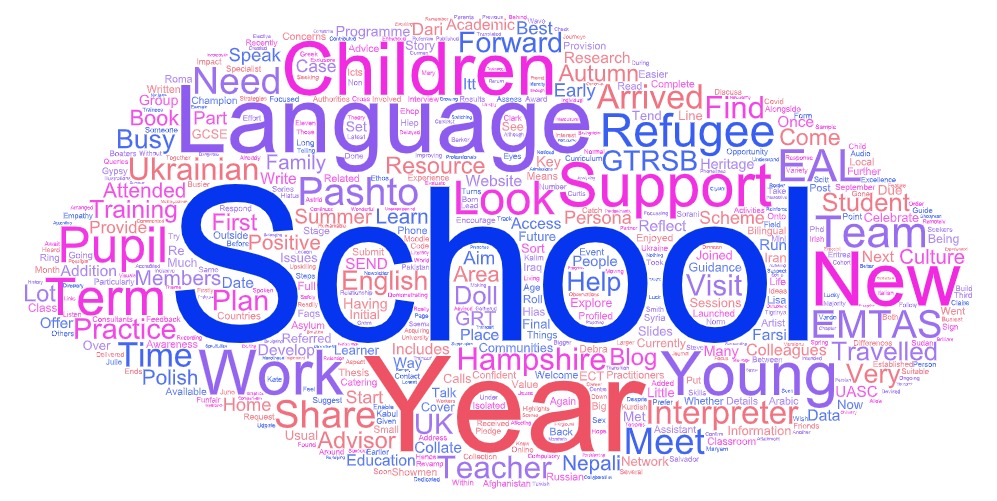

1077 pupils, 60 languages, 70 countries of origin; 2021-22 has been a year like no other. In this blog, we reflect on the highlights of a very busy academic year and share some of the things schools can look forward to after the summer. Notably we discuss our response to our refugee arrivals and Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children, review our SEND work, examine how our research projects are progressing, feedback on our GTRSB work, give an update of developments around the Young Interpreter Scheme, ECT programme and Persona Dolls and celebrate the end of support for Heritage Language GCSEs for this academic year. EMTAS Team Leader Michelle Nye concludes this blog with congratulations, farewells and an update around staffing.

Response to refugee arrivals

As we post this blog, 275 refugee arrivals have been referred to Hampshire EMTAS in 2021-22. These pupils predominantly arrived from Afghanistan and Ukraine with a small number coming from other countries such as El Salvador, Pakistan and Syria. EMTAS welcomed new Bilingual Assistant colleagues to support pupils speaking Ukrainian, Dari/Farsi and Pashto and a lot of work went into supporting and upskilling practitioners in catering for the needs of new refugee arrivals. We delivered a series of online network meetings where colleagues from across Hampshire joined members of the EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor team to find out more about suitable provision. We launched a new area on Moodle to share supporting guidance and resources. We published two blogs – Welcoming refugee children and their families and From Kabul to a school in Basingstoke – Maryam’s story. And we added two new language phonelines to our offer, covering Russian and Pashto/Dari/Farsi.

In the Autumn term you can look forward to further dates for network meetings focussing on how to meet the needs of refugee new arrivals. There will also be sessions where we will explore practice and provision in relation to catering for the needs of pupils who are in the early stages of acquiring English as an Additional Language (EAL). In addition to this, we are planning a blog in which we will interview our new Ukrainian-speaking Bilingual Assistant to share with you the specificities of working with Ukrainian children. The team is also working alongside colleagues from HIAS and HIEP to collate FAQs from queries and observations related to asylum seekers and refugees who have recently arrived into Hampshire.

Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children (UASC)

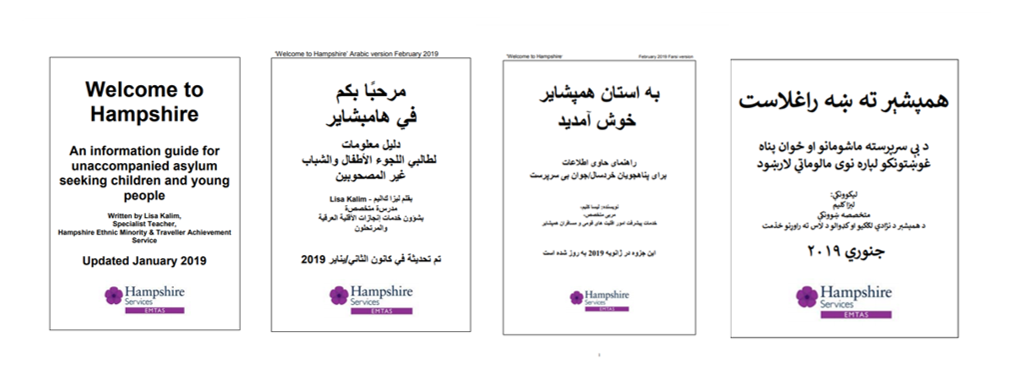

It’s been a busier than usual year for UASC new arrivals too, with 11 young people being referred to us having made long and dangerous journeys to the UK on their own. They have travelled from countries such as Sudan, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan and Eritrea and speak a variety of languages including Arabic, Kurdish Sorani, Tigrinya and Pashto. The majority have been placed in schools outside of Hampshire and so have been profiled remotely, but some are now attending Hampshire schools meaning that we have been able to visit them in person. There is lots of advice available for schools receiving UASC onto their school roll on our website. This includes detailed good practice guidance and Welcome to Hampshire (an information guide written for the young people) translated into several key languages with audio versions also available.

SEND work

The SEND phone line run by Lisa Kalim continues to be well used by schools as their initial point of contact with EMTAS when they have concerns about a pupil with EAL and suspect that they may have additional needs. There have been almost 100 calls made on this line to date this academic year. After school tends to be the busiest time so if you can ring earlier, it may be easier to get through first time. It is helpful to have first read the information on our website about steps to take when concerned that a pupil with EAL may also have SEND and to have gathered the information suggested in the sample form for recording concerns before calling. In many cases advice can be given over the phone without the need for a teacher advisor visit to the school. However, for others a visit by one of our Teacher Advisors can be arranged. This year, our Teacher Advisors have been especially busy with this aspect of our work and have completed over 60 visits since September. These have focused on establishing whether individual pupils may have additional needs as well as EAL or not and also on the enhanced profiling of those for whom a school will be submitting a request for assessment for an EHCP.

Ongoing research

It’s been a catch-up sort of year for Sarah Coles, with a delayed start to her data collection due to Covid affecting the normal transition programmes schools have for children due to start in Year R in September. Through the Autumn, Spring and Summer terms, Sarah has made visits to schools to work with the eleven children who are involved in her research. The children are either Polish or Nepali heritage and they were all born in the UK. This means they have not experienced a monolingual start to life, hence Sarah’s interest in them and their language development.

The children have talked about their experiences of living in two languages – although as it turns out they’ve had very little to say about this. Code-switching is very much the norm for them and having skills in two languages at such a young age seems to be nothing remarkable or noteworthy in their eyes. They’ve also done story-telling activities in their home languages and in English, once in the autumn term and again in the summer. This will enable comparisons to be made in terms of their language development as they’ve gone through their first year of full time compulsory schooling in the UK.

Early findings suggest big differences between the two language groups. The Nepali children tend to prefer to respond in English and most have not been confident to use Nepali despite all demonstrating that they understand this language when it’s used to address them. This has been the case whether they are more isolated – the only child who has access to Nepali in their class - or part of a larger group of children in the same class who share Nepali as a home language. In contrast, the Polish children have all been much more confident to speak Polish, responding in that language when it’s used to address them as readily as they use English when spoken to in that language. This has been the case whether they’re more isolated at school or part of a bigger cohort of children.

The field work ends in the summer with final interviews with the children’s parents and teachers. Sarah then has a year to write up her findings, submit her thesis and plan how best to share what she’s learned with colleagues in schools.

Young Interpreter news

This academic year Astrid Dinneen launched the Young Interpreter Champion initiative. Young Interpreter Champions are EAL consultants outside Hampshire who are accredited by Hampshire EMTAS to support schools in their area in running the Young Interpreter Scheme according to its intended ethos. Currently 6 Local Authorities are in our directory with more colleagues enquiring about joining.

Established Young Interpreter Champions met on Teams in the Summer term to find out how the Young Interpreter Scheme is developing in participating Local Authorities and to plan forward for 2022-23. They also heard more about Debra Page’s research on the Young Interpreter Scheme under the supervision of the Centre for Literacy and Multilingualism at the University of Reading and with Hampshire EMTAS as a collaborative partner.

The aim of Debra’s research is to evaluate the scheme’s impact on children’s language use, empathy and cultural awareness by comparing Young Interpreter children and non-interpreter children. Her third and final wave of data collection took place during the Autumn term 2021. This year is dedicated to analysing her data and writing her PhD thesis. Her chapter on empathy and the Young Interpreter Scheme is complete and she will soon write a summary about this in a future Young Interpreters Newsletter. She also looks forward to sharing results of what is found out in terms of intercultural awareness and language use.

GRT update

It has been a very busy year for the GRT team. Firstly, we will be moving towards using the more inclusive term of Gypsy, Travellers, Roma, Showmen and Boaters – GTRSB when referring to our communities.

As usual our two Traveller Support Workers Julie Curtis and Steve Clark have been out and about supporting GTRSB pupils in schools. The feedback they receive from schools and families is very positive. The pupils look forward to their opportunity to talk about how things are going and they value having someone listen to them and help sort out any issues. Our Traveller team lead Helen Smith has been meeting with families, pupils and schools to discuss many issues including attendance, transport, exclusions, elective home education (EHE), relationships and sex education, admissions and attainment.

Helen has been lucky enough to work with some members from Futures4Fairground who have advised us on best practice when including Showmen in our Cultural Awareness Training. Members of the F4F team also attended and contributed to our schools’ network meeting and to our GTRSB practitioners’ cross-border meeting.

The team was busy in June encouraging schools to celebrate GRT History Month. We devised activities and collated resources around the theme of ‘homes and belonging’. Helen attended an event to celebrate GRTHM at The University of Sussex. It was aimed at all professionals involved in working with members from all GTRSB communities in educational settings. It was encouraging to see so many professionals attending. Helen particularly enjoyed watching a performance of Crystal’s Vardo by Friends, Family and Travellers.

Sarah and Helen have been making plans for celebrating World Funfair Month in September. We have already put some ideas together for schools on our website and hope to develop them further with help from our friends at Future4Funfairs.

Looking forward to next year, as well as reviewing our GRT Excellence Award, we will be looking at how best to encourage and support our schools to take the GTRSB pledge for schools - improving access, retention and outcomes in education for Gypsies, Travellers, Roma, Showmen and Boaters. Schools that complete our Excellence Award should then be in a position to sign the pledge and confirm their commitment to improving the education for all their GTRSB families.

Early Career Teachers (ECT) programme

The Initial Teacher/Early Career Teacher programme that Lynne Chinnery is preparing for next academic year is really coming together. After a large proportion of student teachers stated they were still uncertain how to support their EAL learners after completing their training programmes (Foley et al, 2018), the EMTAS team decided to do something about it.

Lynne has collated a set of slides to train student and early career teachers on best practice for EAL learners by breaking down the theory and looking at practical ways to implement it in the classroom. The sessions cover such areas as supporting learners who are new to English; strategies to help students access the curriculum; assessing and tracking the progress of EAL learners; and information on the latest resources/ICTs and where to find them.

The programme has been made as interactive as possible in order to reinforce learning, with training that practices what it preaches. For example, it provides opportunities for group discussions that build on the trainees' previous experiences. The trainees can then try out the strategies they have learnt once they are back in the classroom.

Lynne Chinnery has already used the slides on a SCITT training programme and the feedback from that was both positive and useful. One part the students particularly enjoyed and commented on was being taught a mini lesson in another language so that they were literally placed in the position of a new-to-English learner. This term, Lynne and Sarah Coles have met with an artist who is designing the graphics for the training slides - once again demonstrating a feature of EAL good practice: the importance of visuals to convey a message. The focus in the autumn term will be a reflective journal for student teachers to use alongside the training sessions.

Heritage Language GCSEs

This has been a particularly busy year for us supporting students with the Heritage Language GCSEs. We received 136 requests from 32 schools. We provided support for Arabic, Cantonese, German, Greek, Italian, Mandarin, Polish, Portuguese, Russian and Turkish. For the first time this year, we also supported a student with the Persian GCSE.

The details of the packages of support we will be offering next year will be shared with you in the Autumn term. You can also check our website. Remember to get your referrals in to us in good time!

We wish all students good luck as they await their results! A big thank you to Jamie Earnshaw for leading on this huge area of work. Sadly Jamie is leaving at the end of the Summer term. Claire Barker returns from retirement to take over the co-ordination of Heritage Language GCSEs from September.

Persona doll revamp

Persona Dolls are a brilliant resource which provide a wonderful opportunity to encourage some of our youngest learners to explore similarities and differences between people and communities. They allow children time to explore their own culture and learn about the culture of someone else. The EMTAS team currently have around 20 Persona Dolls, all of which come with their own identity, books and resources from their culture to share and celebrate.

Now some of you may have noticed that our Persona Dolls have been enjoying a little hiatus recently. What you will not have seen is all the work that is currently going on behind the scenes in our effort to revamp them. Within our plans we aim to provide better training for schools so that you as practitioners feel more confident in using them within your classrooms. Kate Grant is also looking at ways to incorporate technology so that you can have easier access to supporting guidance, links to learn more about the doll’s heritage and space to share the experience your school has of working with our Persona Dolls. EMTAS know that our schools recognise the value of this wonderful resource and look forward to seeing the positive impact they will have on their return.

Finally, a conclusion by Team Leader Michelle Nye

The last time EMTAS topped 1000 referrals was 7 years ago so it has been one of the busiest years we have experienced in quite a while. This was due to the exceptional number of refugee referrals and to a spike in Malayalam referrals whose families have come to work in our hospitals. On top of this we had over 120 new arrival referrals from Hong Kong; these children are here as part of the British Hong Kong Nationals Overseas Programme.

EMTAS recruited additional bilingual staff and welcome Sayed Kazimi (Pashto/Dari/Farsi), Tsheten Lama-North (Nepali), Kubra Behrooz (Dari), Tommy Thomas (Malayalam), Jenny Lau (Cantonese) and Olha Herhel (Ukrainian) to the team.

We are delighted that schools have been committed to improving their EAL and GRT practice and provision and have achieved an EMTAS EAL or GRT Excellence Award this year. Congratulations to St Swithun Wells, Bramley CE Primary, St James Primary, Marchwood Infant, New Milton Infant, St John the Baptist (Winchester District), Bentley Primary, St Peters Catholic Primary, Swanmore College, Poulner Junior, Grayshott CofE Primary, The Herne Primary, Wellington Community Primary, Marlborough Infants, John Hanson, Fleet Infants, Fairfields Primary, Swanmore CofE Primary, Brookfield Community School, Fernhill School, New Milton Junior Elvetham Heath and Red Barn Primary.

We say goodbye to Jamie Earnshaw, Specialist Teacher Advisor, who has been with EMTAS since 2012. During his ten-year tenure, his work has included producing the late arrival guidance on our website, developing our Accessing the curriculum through first language: student training programme now available for pupils in both primary and secondary phases, and for leading on our Heritage Language GCSE work. His are big shoes to fill and we will miss him immensely; we wish him every success in his new venture.

Enjoy your summer holiday and see you again in September.

Data correct as of 30.06.2022

Word cloud generated on WordArt.com

[ Modified: Monday, 25 March 2024, 1:36 PM ]

Anyone in the world

By EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Lisa Kalim

Following last summer’s military evacuation of families from

Afghanistan and a subsequent period in temporary hotel accommodation, many of

these refugees are now permanently settled in Hampshire. The families have been able to start the

process of building new lives for themselves.

For the children an important part of this has been starting school and

being able to attend regularly. This

blog describes the experiences of nine-year-old Maryam as she left Afghanistan and

how her new school in Basingstoke helped her to settle in and subsequently begin

to thrive.

Kabul

Maryam was airlifted by the British military from Kabul airport on the 26th of August 2021, together with her parents and two younger brothers. Her father had previously worked as an interpreter for the British army for several years and was therefore fearful that the whole family would become a target for the Taliban if they remained in Afghanistan.

The decision to leave their home was a sudden one. Maryam was woken in the middle of the night and told to put a few things into a small backpack. Shocked, she hastily packed a few clothes and a bottle of water, grabbed her favourite necklace and then they were picked up by a family friend who had a car. He drove them as close to the airport as he could get and then dropped them off – the roads close to the airport were all blocked by vehicles and large numbers of people on foot who were packed tightly together. It took Maryam and her family several hours to get near to the airport perimeter. By this time, it was starting to get light. Then they had to join the crush to get through the gate and try to work their way towards the front where soldiers were checking papers and making decisions about who could get a place on a flight and who would be left behind. It was incredibly difficult to move forwards because there were so many people and there was no space to move. Maryam was terrified that she would be separated from her family and never find them again. They gradually inched their way forwards, managing to stay together, but many more hours passed and they were still nowhere near the front. It was really hot and there was no shade. They hadn’t brought any food with them, so they were all hungry. There were no toilets. They spent the rest of the day in the crush and into the following evening. Just as it was starting to get dark, there was a loud explosion behind them and they could see smoke rising from just outside the airport close to where they had been earlier. This was shortly followed by the sound of ambulance sirens. Maryam felt numb inside – what was happening to her didn’t seem real, she felt like she was in a movie.

Eventually, sometime in the night, they reached the front. Maryam watched as her father waved his papers at the soldiers, desperately trying to get their attention. He had to keep trying for quite a while but at last a soldier took his papers, examined them and then let the whole family through. They were taken to a runway where they had to wait for several more hours before boarding a military plane. Once they were aboard Maryam quickly fell asleep only waking when the plane touched down in the UK.

Once they had left the plane, they were told to get on a bus that was waiting for them just outside the airport. Maryam had no idea where they were going. She looked out of the window and found that everything looked very different to what she was used to. She was not sure if she was going to like living in England.

Basingstoke

Three months later Maryam and her family were finally able to move from their temporary hotel room to their permanent accommodation in Basingstoke. It was such a relief to be out of the hotel and to have their own safe space at last. For the first time in her life Maryam had a bedroom to herself. She was delighted to discover that it even had a small desk and a chair that she could use to study at home. It had been several years since Maryam had been able to attend school in Afghanistan due to it being too dangerous – the Taliban often targeted girls’ schools as they did not support education for girls or women. There had been many attacks aimed at schools where bombs had exploded resulting in children being injured or killed in the province that Maryam’s family came from. Her father had reluctantly decided that it was safer to keep Maryam at home. He tried his best to continue her education by teaching her at home when he was not working but this was not possible every day. In fact, Maryam was one of the lucky ones in terms of being able to access at least some education as about 40% of children in Afghanistan are not able to attend school at all.

Shortly after moving into her new home Maryam was hugely excited to find out that she had been given a school place at her local primary school. She had walked past it a few times on the way to the shops so knew what it looked like on the outside but had no idea what it would be like inside or what kind of lessons she would have. Then she started to worry about how she would understand what her teacher was saying because she didn’t know much English. Her father told her that they had been invited in to speak to school staff and that she would find out more then. He said that he was sure that they would do everything they could to help her and that she should try not to worry.

A few days later Maryam and her father visited her new school. They had a good look around the whole school with Maryam’s father acting as an interpreter so that Maryam could understand everything that was being said. Maryam was amazed at how different it was compared to her old school in Afghanistan. The classrooms themselves were much bigger and there were only about 30 children in each class. She had been used to smaller classroom sizes with up to about 60 children in each, packed in very close together. There were no individual desks – instead the children sat in groups around tables. Maryam was puzzled to see that not all of them faced the front. There were lots of pictures and children’s work on the walls – this made it seem much brighter and more colourful than what she was used to. All the classrooms had large electronic screens on the walls at the front and Maryam saw teachers using these to show their pupils lots of different things – back in Afghanistan her teachers had just had a board at the front that they wrote on, and the pupils had to copy what they wrote into their exercise books. Maryam didn’t see this happening here and wondered how she would know what her teacher wanted her to do. Another strange thing that she noticed was that for quite a lot of the time the children were talking amongst themselves whilst doing some writing in class – this would not have been allowed in Afghanistan and if you were caught talking, you would be punished.

Maryam was introduced to her teacher and was told which classroom would be hers. The teacher explained what Maryam would need to bring to school each day and where she could hang her coat and bag. She also showed her where to line up in the morning and told what time she had to be there and when school finished. Maryam was surprised that the school day was so long in Basingstoke – back in Afghanistan her school day had only been about three and a half hours long with another shift of children arriving in the afternoon. However, she felt reassured that she knew what to expect. Most importantly she had also been shown where the toilets were as she had been worrying about not being able to ask about this. Maryam was also introduced to a girl called Isobel who was going to be her ‘buddy’ on her first day. She seemed very friendly, and Maryam felt happier knowing that she wouldn’t be left on her own.

The next day Maryam started at her new school. She felt a strange mixture of excitement and nervousness but visiting the school the day before had helped her to feel less worried than she would have been if she hadn’t already had the opportunity to visit the school.

Unbeknown to her the school had been busy preparing for her arrival. They had identified some actions that they could take and strategies that they could use to best support Maryam as she started her full-time education in the UK. They ensured that Maryam was placed in her correct chronological year group, Year 5, and her teacher made sure that she was included in the same types of activities that the other children were doing in class, but with appropriate differentiation and lots of peer support. She was placed in a middle ability group with children who would be able to assist her if needed and who could provide her with good models of English. They understood that withdrawing her from the classroom for interventions or to ‘teach her English’ would not be a helpful approach and that what she needed was to follow ‘normal’ school routines as far as possible. They were also very mindful that Maryam had been through a very traumatic experience in the way she left Afghanistan. She had also had to leave almost everything behind in terms of possessions, extended family and friends at very short notice to move to an unfamiliar country where her family knew no-one. Because of this, the school decided that initially their focus should be on providing excellent pastoral care, ensuring that Maryam settled into the school well and was happy rather than concentrating on her academic attainment and progress (which could be addressed later).

The school also considered cultural differences and how these might affect Maryam at school. One area where they felt this could be relevant was around the school’s PE kit and changing facilities. Mindful that Maryam would most likely not feel comfortable changing for PE in front of boys they ensured that she had a private area in which to change and also allowed her to wear long track suit trousers instead of shorts for PE.

The school was also very aware of the importance of finding out as much as possible about Maryam’s background including details of her previous schooling and her skills in her first language, Pashto. The school therefore put in a referral to EMTAS soon after Maryam joined the school so that profiling could be carried out. They also kept in regular contact with Maryam’s father to ensure that there was good home-school communication.

It’s still early days in terms of how long Maryam has been in school in the UK but the early signs are good. She seems to have settled and is joining in with class activities non-verbally. Her teacher has high expectations of her going forward. Her father reports that although she is finding school very tiring, she is enjoying attending.

Hampshire EMTAS have advice and guidance about refugees and

asylum seekers on our website here. We have also produced a comprehensive good

practice guide which schools receiving refugees and asylum

seekers in Hampshire will find useful. There are more resources on our Moodle.

[ Modified: Tuesday, 25 January 2022, 11:18 AM ]

Anyone in the world

In this blog, the Hampshire EMTAS Teacher Team considers what best practice might look like in relation to catering for the needs of refugee children on roll in Hampshire Schools.

In recent months, Hampshire has hosted a number of refugee families from Afghanistan, some of whom will remain in the county permanently whilst others will eventually be found a permanent home elsewhere. The children of these refugee families are starting to be taken onto roll at schools across the county, and this has raised a number of questions as colleagues have sought advice on how best to streamline support at this vital point in the children’s lives.

First and foremost, at the point of referral to EMTAS it has become apparent that not everyone is confident when it comes to telling the difference between an asylum seeker and a refugee. To cut to the chase, the term refugee is widely used to describe displaced people all over the world but legally in the UK a person is a refugee only when the Home Office has accepted their asylum claim. While a person is waiting for a decision on their claim, he or she is called an asylum seeker. Some asylum seekers will later become refugees if their claims for asylum are successful.

The recently-arrived Afghan refugee children are here with their families and because of this they benefit from greater continuity in terms of support from their primary care-givers. Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children (UASC), on the other hand, are minors who are here on their own and therefore don’t have the support of their close families. UASC are accommodated in the care system in the UK but their status in the longer term remains in question. They will be claiming asylum, which – if they are successful – will give them indefinite leave to remain and refugee status. This will give them the right to live permanently in the UK and to pursue higher education and/or work in the UK. Check the EMTAS guidance for more detail on this point.

Moving on to talk about refugees, in many ways the needs of

refugee children are very similar to those of any other international new

arrival, hence staff in schools should, in the main, adopt the same EAL good

practice with these children as they would any others. There are, however, some additional things to

bear in mind.

Refugee children (as well as UASC) may have had to leave their country of origin suddenly, bringing with them very few of their personal belongings and leaving much behind. Because of this, some may experience a greater sense of loss than children whose move to the UK was undertaken in a more planned way. Some refugee children will have left behind members of their extended families as well as friends, favourite toys and pets (where keeping pets is part of their culture), and may be concerned for their safety or not know their whereabouts or even if they are alive. This can be compounded by having little opportunity to communicate with them to check if they’re OK. Older children are likely to be more aware of and affected by this than younger ones, and their awareness may be heightened by conversations within their household as parents talk about and begin to process the events that brought them here.

Some refugee children will have experienced unplanned interruptions to their education, especially those who have spent time in refugee camps en route to the UK or those who have travelled with their families through various countries. Lack of facilities might mean that some have missed opportunities to keep up with their learning, hence there may be gaps. The longer the gap, the more they will have missed – hardly rocket science, but something to bear in mind when thinking about reasons why a child’s reading and writing skills may not be as secure as would normally be expected. The advice with this would be to clarify each child’s education history with parents and then to consider what arrangements might be put in place to help plug any gaps – without causing them to miss even more eg through ill-timed/too many withdrawal interventions (see EMTAS Position Statement on Withdrawal Provision for learners of EAL).

For most refugee children, routine really helps. They benefit from knowing what each school day will hold, so things like visual timetables are helpful. They also benefit from being supported to quickly develop a sense of belonging in their new school. Use buddies – including trained Young Interpreters – to support them as they adjust to their new surroundings. Bear in mind that the less-structured times such as break and lunch times can be more difficult for a newly-arrived refugee child, so check that they are being included and are joining in with play with other children. Teachers may find it helpful to teach some playground games in the relative safety and calm of the classroom, with input and support from other children in their class, with the idea that these games can then transfer to the outside areas.

Support from their peers will be key to the induction and integration of a newly-arrived refugee child. Sit them with peers who can be good learning, behaviour and language role models. Try to match them with peers who are of similar cognitive ability. Remember to reward all children involved with praise where things have gone well eg if they have shown the new arrival their book or repeated an instruction or the new arrival has accepted support from a peer or tried to involve themselves in a task or whatever. With younger learners, consider using a Persona Doll to explore ways of supporting the new arrival with your class.