User blog: Astrid Dinneen

Written by Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Chris Pim

As a trainer I often find there can be a wide range of assumptions or even misconceptions about the effectiveness of digital translation tools for supporting learners of English as an additional language (EAL) and their families. Whilst there is no doubt that these tools are continuing to improve over time, they do have their limitations. So what can we say about their effectiveness - in what contexts are they useful and how can we make best use of them?

The first point that is worth mentioning is that these tools won’t be putting translators out of a job any time soon. It is certainly the case that these tools are not reliable enough for formal written translation and there are many stories, perhaps apocryphal, of nuance being completely lost because a word like ‘detention’ translates as ‘prison’. Moreover, clarification can’t easily be sought once the translated material escapes into the real world. We should also be cautious about replacing professional interpreters in situations where accuracy of face to face communication is essential, such as in formal meetings, particularly where the topic involves sophisticated or esoteric subjects and where there may be additional safeguarding issues.

So what place do these tools have for communication and curriculum-related support? It might help initially to clarify the distinction between standalone translation devices or scanning pens and other solutions that utilise the power of the internet. The former examples have been programmed with a specific set of in-built translations for vocabulary and stock phrases. These devices will be fairly accurate so long as, particularly for vocabulary, the user can pick the correct option from a range of homographs or grammatical constructs. The latter versions, online tools, will be more unpredictable but potentially much more powerful, especially when used judiciously.

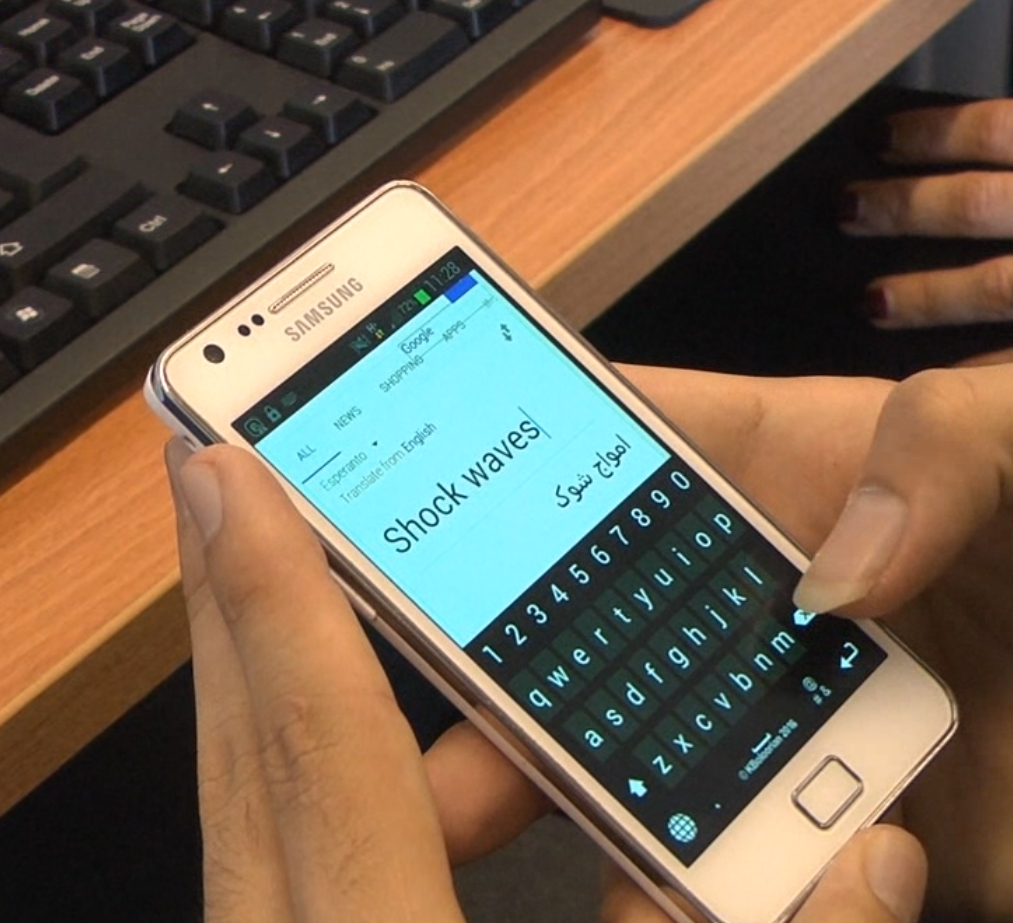

Modern online tools use the immense processing power of neural networks, piecing together their output from known good translations in the target language that exist around the World Wide Web. This is how the system learns and improves and in fact certain language learning tools like Duolingo are helping by contributing to the accuracy of online translated materials. Connected devices such as phones and tablets and appropriate apps (such as SayHi and Google Translate) are beginning to transform how EAL students can benefit from using their first language skills. For example, using Google Translate a user can scan printed text with the camera on their chosen device and, as if by magic, the text will change in real time into target language. Similarly, where before the effectiveness of online translation required a user to be able to read rendered text, now a user can use the listening capability of a mobile device to register speech and read out an oral translation in a naturally synthesised accent for the target language.

This is where digital translation becomes genuinely useful. So, for ad-hoc communication, whether face-to-face or via video conferencing technologies like Skype, the conversation is mediated by the participants who can check for clarification in the moment and fall about laughing if it all goes wrong. Meaning is more important than grammatical accuracy in this context. Moreover, for more academic work users can type or talk and get instant translation which they can mediate for themselves to enhance their access to the curriculum.

Practitioners can use these technologies to communicate with students in lessons. They could translate the aim of the lesson or a key concept and also prepare resources such as bilingual keyword lists, notwithstanding the complexities of ensuring they choose the correct words. With short paragraphs, removing clauses can produce more accurate translations. Additionally, it is also possible to reverse translate to check for accuracy.

Many of these tools are free, or really low-cost, so what’s not to like? Try them and encourage your EAL learners as well. You may be surprised at the results!

One question often asked is ‘What are the differences between teaching English as an Additional Language (EAL) and teaching English as a Foreign Language (EFL)? They’re practically the same thing, aren’t they?’ Lynne Chinnery, Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor on the Isle of Wight clarifies how these approaches to English language learning are distinctively different from each other.

Who are EFL and EAL learners?

English as a Foreign Language (EFL) is used to refer to both adults and children learning English in a non-English speaking country or in the UK for a limited period of time, such as a summer course. English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) mainly refers to adult learners of English in the UK attending English language classes. English as an Additional Language (EAL) is usually used to refer to children who are living and attending school in the UK and whose first language is not English.

Practitioners should remember however that ‘pupils with English as an additional language are not a homogeneous group’ (Naldic, 2012a); their age, background, previous education and previous experience of language learning will all play a part in shaping the way they learn English. Practitioners will therefore need a variety of EAL specific approaches to help each individual along his or her learning path.

What difference does it make?

One of the main differences between EAL and EFL is that because EFL is mostly taught in non-English-speaking countries, EFL students have limited exposure to English. They may have between one and five English lessons a week (the majority from my experience having only one to three lessons) and for many students, this time in the classroom will be the only time that they are immersed in English. They will usually be given English homework and, depending on their level, may even watch English TV programmes or listen to English songs outside the classroom, but on the whole, they will not have extended periods of communication in English, apart from their time inside the classroom.

EAL students, on the other hand, have a completely different experience. Not only are they immersed in English all day, five days a week, both in the classroom and in the playground, but they will also hear English outside school too. Even if they speak their first language at home or use it as a tool for learning, which we highly recommend, they will be listening to English all around them whenever they go out, and will eventually be communicating in the language outside as well as inside school.

One result of this is that EAL learners will normally acquire English much faster than learners of EFL. Even so, learning a language is a long process and EAL learners can take between 7 to 10 years to catch up with their monolingual peers. What is interesting to consider is the way in which they pick up the language. EAL students have time to listen to lots of talk, especially if they are seated with peers who can act as good language models. Being immersed in the language, they will begin to copy what they hear, experiment with it and eventually shape it for themselves. With lots of speaking opportunities in a supportive atmosphere, as well as a teacher and peers to model new language and recast it correctly, their confidence, fluency and accuracy will flourish. EFL students also need many opportunities for practice, but because their exposure to English is more limited, there will be much less time to develop the patterns and rules of language themselves in such a natural way. Because of this, they are likely to need more explicit instruction of grammar and syntax than the EAL student.

Another difference to bear in mind between EFL and EAL, is the fact that the EAL learner is usually alone or in a minority language group within the classroom, while EFL learners often share the same first language. This can make the initial stages of learning much more stressful for the EAL student. Sometimes early stage EAL learners also experience what is known as the ‘silent period’, where the learner begins to absorb the language around them but is not yet ready to speak. Although an EFL student may suffer some anxiety before their first lesson or two, this is not usually so pronounced or prolonged. Imagine how different it would feel if you were learning French in a class of English speaking peers at the same level as yourself compared with learning French in a class of French native-speakers!

EAL learners also differ from their EFL peers as, while they are learning English, they are also learning the school curriculum - in English, which means they have the difficult task of trying to learn English, access the curriculum and catch up with their peers – all at the same time! For this reason, focussing on vocabulary lists that have little or no connection with the curriculum, such as colours, pets or vegetables, is not good practice.

Are there any similarities?

While we are considering the differences between EAL and EFL learners, it is also important to remember that there are many similarities between the two disciplines and that what is good practice in one field can also be good practice in the other. Many methods that are recommended when working with EAL students are also used with EFL learners, such as the use of visuals, role play, paired activities and collaborative group tasks. In fact, these methods work well for all students, not just those learning EAL. In any English language classroom, the form and function of language will still need to be explored but the way language is taught has changed, even in the field of EFL. For example, endless exercises practising one particular grammatical structure, without context or the opportunity to experiment with it in natural conversation, will be of as little benefit to the EFL student as it is to the EAL student. Talk is creative: it is spontaneous and unpredictable and teachers should therefore not only plan activities which enable the student to apply the language they have learnt, but also to use it in real conversations in order for them to grow into independent learners (Naldic, 2012b).

The world of EFL has recognised this shift in methodology and most EFL course books now reflect modern approaches to language learning. We have torn out the language labs and have introduced many more opportunities for spontaneous conversation, that provide a platform to practise the structures and vocabulary taught, rather than an overreliance on drilled exercises with no avenues for real expressiveness. In this way EFL has become more in line with the pedagogy of EAL, where ‘The active use of language provides opportunities for learners to be more conscious of their language use, and to process language at a deeper level. It also brings home to both learner and teacher those aspects of language which will require additional attention’ (Naldic, 2012b).

Accessing the curriculum

EAL and EFL students will have very different experiences on their language journeys, not only because of the differing amounts of exposure to English, but also because of the purposes for which they are learning the language; EFL learners are learning English as a discrete subject whereas EAL learners are learning the curriculum through the medium of English. The good news is there are many useful strategies which work well for both EFL and EAL students, and have been proven to be good practice for all children, including native-speakers. However, practitioners working in the mainstream setting should remember that the curriculum provides the context for English language learning and therefore EAL strategies should be planned into lessons to support pupils’ access to the language demands of the curriculum. Check out Hampshire EMTAS and the Bell Foundation for more ideas.

References

Naldic (January 2012a) Pupils learning EAL [online] https://www.naldic.org.uk/eal-teaching-and-learning/outline-guidance/pupils/ (accessed 09.05.2018)

Naldic (January 2012b) The Distinctiveness of EAL Pedagogy [online] https://www.naldic.org.uk/eal-teaching-and-learning/outline-guidance/pedagogy/ (accessed 09.05.2018)

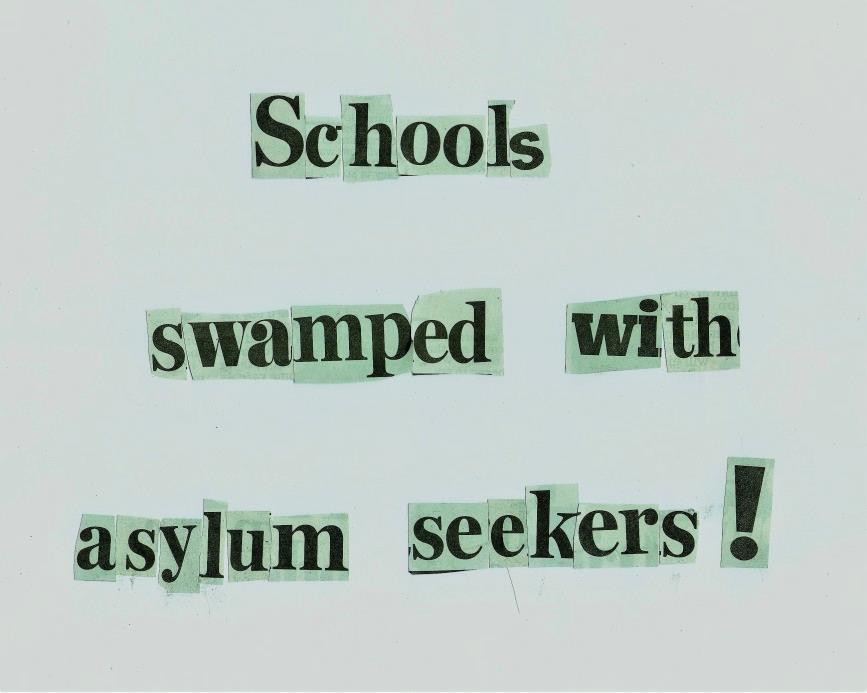

Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Lisa Kalim separates fact from fiction

If you read and believe certain tabloid newspapers you may well have reached the conclusion that UK schools are struggling with a large influx of asylum-seeking children and young people. However, this view is not supported by the most recent data released by the Home Office in February 20181. These give the details of all asylum applications made by children in 2017 and compare the data with the previous four years. Applications from Unaccompanied Asylum Seeking Children (UASC) and those that arrived in the UK with an asylum seeking relative/guardian are included in the data so all children who were seeking asylum during this period have been considered.

How many asylum seeking children started at British schools in 2017?

Probably far fewer than you think. In 2017 a total of 2,206 children applied for asylum in their own right, down 33% from the previous year. Of these, 71% were aged 16-17, 22% were aged 14-15 and 4% were aged under 14 with a further 3% of unknown age. All are entitled to a school or college place. An additional 2,774 applied as dependents of adult asylum seekers, making a total of 4,980 children. Some of the latter were under the age of 5 years at the time of their relative/guardian’s application and so would not all need a school place straight away. When you consider that there were 8,669,085 pupils in UK schools in 2017 (DfE, 2017)2 but only 4,980 of these were newly arrived asylum seekers, it would seem clear that schools are not being swamped by asylum seekers. How can they be when one year’s worth of newly arrived asylum seeking children make up less than 0.05% of the total school population?

But don’t some areas get more than their fair share of asylum seeking pupils?

The UK operates a policy of dispersal for asylum seekers to avoid particular areas receiving much larger numbers than others. This has been in place since 2000 for adult asylum seekers and their families and whilst it is not a perfect system (it has had criticism for removing new arrivals from their extended family in the UK, for example) it has meant that any particular area should not receive more than one asylum seeker per 200 of the settled population and therefore no area should feel ‘swamped’.

For UASC, a new scheme called the National Transfer Scheme has been in place since 2016. Similarly, it limits the numbers of UASC for whom any particular Local Authority is responsible to 0.07% of its total child population. Again, this should mean that no single area should receive a larger number than it is able to manage.

Didn’t the UK take in lots of children when the Calais Jungle closed?

Between 1st October 2016 and 15th July 2017 only 769 children were permitted to move to the UK from the camps in Calais. There were 227 children from Afghanistan, 211 from Sudan, 208 from Eritrea and 89 from Ethiopia. The rest came from a variety of countries, with fewer than 10 children from each. Nowhere near enough to swamp UK schools.

Where have the rest of the children come from?

Sudan is now the country of origin for the largest number of UASC. 89% of all applications in 2017 were from the following 9 countries: Sudan (337), Eritrea (320), Vietnam (268), Albania (250), Iraq (248), Iran (213), Afghanistan (210), Ethiopia (74) and Syria (41). 89% of these children were male. For female UASC Vietnam is the most common country of origin.

For children arriving with a relative or guardian, the countries of origin are similar but with the addition of Pakistan, Bangladesh and India. Numbers from Sudan and Vietnam have increased significantly since 2016, whereas numbers from Iran and Afghanistan have decreased. In contrast to UASC, around 66% of children that arrived with a relative or guardian are female.

How many children are granted refugee status and allowed to stay in the UK?

1,998 initial decisions relating to UASC were made in 2017. Of these 1,154 (58%) were granted refugee status or another form of protection, and an additional 378 (19%) were granted of temporary leave (UASC leave). A further 23% of UASC applicants were refused. This will include those from countries where it is safe to return children to their families, as well as applicants who were determined to be over 18 following an age assessment.

For children with a parent or guardian their decisions are linked to their adult applicant’s. So, if their parent or guardian is granted refugee status, the children are too. In 2017, 68% of asylum applications (excluding UASC) were refused. Only 28% were successful and an additional 4% were granted other types of leave. The numbers being granted refugee status are the lowest that they have been in the last 5 years. The numbers of refusals increased in 2017 compared to previous years. Pakistan, Bangladesh, India and Nigeria have well above average refusal rates, whereas children from Iran, Eritrea, Sudan and Syria are most likely to be granted refugee status. Those refused can choose to appeal the decision. In 2017 only 35% of appeals were allowed, while 60% were dismissed. This means that a large proportion of the asylum seeking children arriving in our schools will not be permitted to remain in the long term.

So, are our schools being swamped with asylum seekers or not?

Based on the facts, I would say definitely not but you make up your own mind. Some schools may have more asylum seekers than others but this does not mean that they are swamped. The numbers arriving overall are falling.

References

1 Refugee Council (February 2018) Quarterly asylum statistics [online]

https://www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/assets/0004/2697/Asylum_Statistics_Feb_2018.pdf

2 Department for Education (June 2017) Schools, pupils and their characteristics: January 2017 [online] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/650547/SFR28_2017_Main_Text.pdf

Written by Hampshire EMTAS Bilingual Assistant Eva Molea, this is the second instalment in a series of blog posts focussing on the experience of parents of pupils with EAL. Read Chapter 1 before enjoying this new post.

March 2015

I needed a strategy. And a pretty good one, too. I needed to make my daughter Alice’s life in the UK enjoyable, cure her homesickness and support her learning. Any of these tasks on their own would have been hard enough, but all together I was not sure I could make it. So, I rolled up my sleeves and started working on our new environment.

An enjoyable life in the UK

The first thing I had to do was to make Alice comfortable

in her new house. So, we made a lovely and cosy room for her, with some of her

toys from Italy, many books in Italian and some in English (now we have loads of

both and we do not know where to put them…). Since she was in the “pink

period”, we chose some of the furniture accordingly, and some decorations as

well. We showed her where everything was in the house, so she could quite

independently have access to what she needed. We taught her how Sky worked, so

she could watch TV whenever she wanted. At the beginning, we allowed her to

watch much more TV than we normally would, but we believed that TV would offer

a good model of English, so she had free access to it for quite a while. In the

first days, she would just watch “Tom & Jerry” or the Warner Bros. cartoons,

as she could follow the story even if she did not speak a word of English. Then

she gradually moved to other programmes without our suggestion, and soon

started to watch feature films, even if with a bit of a struggle.

Then we moved to explore the surrounding area. We went to the adventurous discovery of the neighbourhood and then of our small town. We took her to the playgrounds and to the cinema, to the local museum for a play day on dinosaurs, shopping for her school uniform and for food, encouraging her to try new flavours. We took her for a full English breakfast and to eat out. In general, unless it was raining cats and dogs, we took her out every week-end, even if it was just for a walk into town. But the best thing we did was to enrol her to the dance school at the local leisure centre. Since she was very little, she had asked me to go to a dance school, so now she was in for a treat. It turned out to be a great decision because Alice had the chance to meet with other children and make different friends from the ones she had at school. Also, since she had already practised sports in Italy, she knew she had to imitate the teacher, so she could join in quite easily. Her dance teachers were lovely and this helped a lot. She still dances three times a week with the same eagerness of the first days.

Defeating homesickness

To overcome homesickness was definitely a harder task. Alice missed her grandparents, her friends, her teachers, and the entire little universe she was used to live in. We tried to recreate the life she had in Italy: we did not change habits, but stuck to the usual routines. Doing everyday exactly the same things that she was used to in Italy made Alice feel safe and secure. She knew what was coming next, and these little certainties helped her find her way through the bigger changes our lives were going through.

The other thing that was very helpful was that I did not work at that time. We had decided, with my husband, that I would have not looked for a job until September 2015, because I wanted to make sure that Alice had settled in nicely and everything was going well. My husband had moved to the UK in 2013, so Alice and I had been on our own for quite a long time. At that time, I used to work from Monday to Friday from 4.30 to 8 pm. This meant that Alice had to stay with the grandparents, who would alternate in the babysitting during the week. She was looking forward to an intense one-to-one time with mummy, which was served to her on a silver tray when we moved to the UK. She really made the most of it: she would ask for girls’ night in, to go to the cinema, to go shopping. Basically, she really enjoyed being part of a team of two. Yahoo!!

Technology also played an essential role in defeating homesickness. Daily video-calls with the grandparents made distances smaller, and Alice would happily take the tablet to her room and talk to them about her day or play games with them on Skype. We often spoke to our closest friends via Skype, so the children also kept in touch. This also created great excitement the first times we went back to Italy, because they would not feel like strangers when they met after a long period.

So far so good, but now how was I going to help her with her learning since I am an EAL person myself? And with a strong Italian accent too (they say)? Find out in the next chapter of my Diary of an EAL Mum! In the meantime, why not browse the 'For Parents' tab on the Hampshire EMTAS website?

Written by Sarah Coles, Hampshire EMTAS Deputy Team Leader

![Alexander Bassano [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e3/Queen_Victoria_by_Bassano.jpg/256px-Queen_Victoria_by_Bassano.jpg)

Alexander Bassano [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

In the Spring 2018 edition of History Matters, a Hampshire Inspection and Advisory Service publication, a Primary Practitioner said of the subject, “…history is exciting to children when they feel immersed in their learning. The more they see the relevance history has to them, the more excited and interested they will be.” History teaching can, and should, help children see the links that exist between their cultures, traditions and religions and the present day and in order to achieve this, the history curriculum in primary phase is often worked into topics. Lots of schools include a focus on The Victorians. 20 years ago, I taught it in Year 5. More recently, I observed the topic being delivered in a school that had been experiencing a rise in its pupil diversity.

I was not surprised, on walking into the Year 4 classroom at the beginning of this topic, to see a display about The Victorians on the wall. What did cause me to do a double-take was the choice of noteworthy Victorians portrayed therein: Queen Victoria (of course), Darwin, Alexander Graham Bell, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Florence Nightingale. What the display said to me was that the Victorian era had happened in a hermetically sealed capsule, with nothing of value contributed to human civilisation by anyone who wasn’t white or British or male, preferably all three.

Whose history was this that the children were learning about? A balanced, world view of the nineteenth century it most certainly was not. Then I started to wonder how the child from Poland, about whose progress I had come in to advise, would be enabled to make links with his own culture and heritage through this version of history. Would it help him better understand the lasting value of contributions to literature from Poles such as Józef Korzeniowski, better known by his pen name, Joseph Conrad? Or to medicine by Marie Skłodowska Curie, a Polish and naturalised-French physicist and chemist who conducted pioneering research on radioactivity. She was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, the first person and only woman to win this coveted and prestigious award twice. But she didn’t feature on the display either.

Also notable by her absence was Mary Seacole and for me, there was no excuse for this as there are plenty of resources to support teaching about this Jamaican woman’s role in the Crimean war and her contributions to nursing. I wondered if she would still be skipping class the following year, when a couple of children of black Caribbean heritage would be learning about the (white British) Victorians. Of course, she is not the only black person who made a contribution to society during the Victorian era. Less well-known but just as important is the work of Lewis Latimer, the only black member of the Edison Pioneers, who developed the little filament in light bulbs to make it last long enough for the electric light to rapidly replace gas lighting in our homes, streets and workplaces. Or Elijah McCoy, most famous for developing lubrication systems for steam engines.

If education is really to prepare children for life in an increasingly diverse society, we are going to have to relinquish the Anglo-centric view of history that formed the diet of my own history lessons back in the 70s and 80s in favour of approaches that better represent the pupils in front of us and the communities that surround and feed our schools today. Hampshire teachers are fortunate indeed to be able to access the Rights and Diversity Education (RADE) Centre, which is situated right next door to the History Centre. Both centres contain a wealth of resources to help teachers diversify the teaching and learning experiences of Hampshire’s schools. Back to ‘History Matters’, the article to read is ‘Teaching forgotten history: the SS Mendi’, about a ship that sank off the coast of the Isle of Wight on Wednesday 21 February 1917 after colliding with another ship, blinded by thick fog. Nearly 650 people lost their lives in the tragedy, many of them black South Africans from the South African Labour Corps. Now there’s something new to find out about, and a way in which we can raise awareness of the multiplicity of histories that are interwoven into all our cultural pasts.

A small scale piece of research into the ‘Any other White background’ (WOTH) ethnic group in Basingstoke & Deane painted a fascinating picture of the experiences of Polish families in UK schools. Parental engagement and home-school communication emerged as an important area for both parents and practitioners – and an aspect of EAL practice that can be difficult to get right.

What are the challenges?

Despite schools’ best efforts, induction can be a delicate time. Parents may struggle to get to grips with school systems, such as getting uniforms right, understanding timetables, knowing how to pay for school dinners, learning about the purpose of different virtual learning environments, etc. – whilst having to fill out forms in an unfamiliar language.

Keeping up to speed with the school calendar might be another difficulty. Parents of EAL learners may struggle to understand letters concerning events such as parent evenings, trips, data collection, and other special occasions such as sports days and INSET days. In fact, the very use of acronyms such as ‘INSET’ is sometimes another hurdle for EAL parents who are new the UK system and often also new to English, especially when these acronyms can be confused for a common everyday term like ‘insect’!

Parents are very keen to support their children with homework and whilst subject knowledge may not necessarily cause them concern, instructions and key words are more problematic due to the more academic nature of the language. However most of all, parents seem to struggle with never being quite certain whether or not they are in the loop. Often, support comes in the form of an EMTAS Bilingual Assistant who is able to interpret for school systems, routines and curricula. Watch this video clip to learn about their experience.

What’s helpful?

In addition to the use of bilingual staff, parents find a simple text message is very helpful in reinforcing the content of school letters, especially when these contain a lot of information to process. Text messages offer condensed details highlighting the most important facts e.g. dates and times of meetings, things to bring to school, reminders, etc. and help parents to keep track of what is happening and when. Yet this is not always a system in place in all schools.

Other parents are another important resource for families. When unsure about any aspect of school life, EAL parents may look to other parents – EAL as well as English-only. However whilst other parents may be a source of reassurance for some, those who aren’t confident with their English to approach other parents may continue to feel lost and isolated at pick up and drop off times. Some schools have tackled this issue by approaching established parents to become helpers in order to offer support to newly-arrived families.

Receiving feedback from their child’s teacher at the end of the day is another way for parents to feel reassured. In our study, EAL parents said they appreciated school practitioners initiating a conversation about how the children had coped during the day, what they had achieved and what they needed to work on. Sometimes, a thumb up and a word of praise was enough to alleviate parents’ anxieties. This was even more appreciated when parents weren’t confident to take the first step to approach staff themselves. In some cases, EAL parents still felt they were only approached by classroom staff when their child had done something wrong.

EAL parents spoke about the advantages of knowing what was coming up in class from one week to the next. This gave them opportunities to discuss topics in advance at home and in their first language, allowing their children to take a more active part in lessons. Parents found general information shared on the school website about what the children were to learn over the half-term less useful because this information contained less details and didn’t focus on the particular needs of their child.

Next steps

A network meeting was held in Basingstoke to share findings from the research with local infant, junior and secondary EAL practitioners. Delegates discussed specific aspects of home-school liaison they wanted to improve at their school and collaborated on a checklist. To follow up on the practice discussed at the network meeting, practitioners at The Vyne School organised a coffee morning event for parents of EAL learners joining Year 7. The event was attended by key staff along with the school’s Young Interpreters who spoke to the children and families and gave tours of the school. The event was well-attended by pupils and parents from a range of feeder Primary schools who felt supported in their transition to Secondary education.

What action would you take to help improve home-school liaison at your school? Over to you now: read the full research report, learn about the First Language in the Curriculum (FLinC) project, set up the Young Interpreter Scheme® and share the strategies you have found most successful at your school in the comment box below.

Written by Hampshire EMTAS Bilingual Assistant Eva Molea, this is the first instalment in a series of blog posts focussing on the experience of parents of pupils with EAL.

March 1980

Many moons ago, when I was nearly 5, my dad decided to apply for a temporary position as plastic surgeon at Queen Victoria Hospital, in East Grinstead, and was luckily appointed. So, we packed our entire house, the useful and useless (silver cutlery included because one could never ever think of dining without one's own silver fork!), loaded our blue Alfetta and embarked on the three day trip that would change our lives.

It was early 80s, and a very exciting time to be at Queen Victoria Hospital with many other people from all over the world: Australians, French, Israeli, Egyptians, Irish, Italians, just to name a few. And, obviously, some Brits as well! It was also very exciting for us children, all attending the same primary school.

This is the background of my personal experience as an EAL child. I will not say that it was easy at the very beginning - name it the first month. The sense of deep isolation for not having a child to talk to and who understood me was overwhelming and my mum, who did not speak a single word of English, had to do everything in her powers to keep me entertained.

Then I started going to school in Year 1 and it was a blessing. My mum felt relieved (and we all know that a happy mum has happy children) as I picked up the language very quickly and made many friends, making her juggling skills no longer needed.

Besides taking me out of my linguistic isolation, the school gave me much more: thanks to the empiric approach of the British scholastic system, I developed strong observational skills and a genuine curiosity towards what I was being taught, which have been my main features through all my years at school and university. It taught me to challenge what I was learning to prove it right. It helped me develop a very rational approach to everything and the ability to analyse. Should it not be clear enough, I am still very grateful to the system. Also, the environment was amazing: massive playground with forts and a field at the back which had no boundaries. My classroom was big enough to host 30 children, plus a play-pretend corner, a big carpet, loads of toys and walls covered with pictures and resources to support our learning.

Unfortunately, my EAL experience came abruptly to its end after just one year because my dad's contract expired and we repacked all our house plus some other souvenirs, loaded again our Alfetta and headed south. Back to Naples, Southern Italy. I could have never imagined, at the time, that my own daughter would follow my steps.

February 2015

We packed our house, with all its useful and useless clutter, shipped it to the UK - how smart! - and moved in February 2015, my daughter being nearly 6 and halfway through Year 1. Strong from my personal experience, I moved quite light-heartedly. At the end of the day, how hard could it be?? This is when I learnt that every child is different, despite genetics. It also made me understand that I had always seen the whole issue of moving from a happy child's perspective, not from a sensible adult's one. I was not prepared. Not at all.

Fortunately, school started one week after we arrived, and with a school trip to the HMS Victory on day 1. What a great start! A. was very impressed and this put her in a good disposition towards her new school. As soon as her teacher introduced her to the class, a girl came and took her to line up. An unexpected act of kindness that changed one of my most dreaded days into a lovely and very informative school trip - did you know that when Admiral Nelson died he was put in a barrel of rum to be preserved for his funeral?

But the linguistic isolation struck her quite soon, so we had the before-going-to-school tantrum and the after-school one. The "I want to go back to Italy right now" desperate cry and the unintelligible sobs that showed all her frustration at not being able to function as well as she was used to in Italy.

But I was not prepared to give up. Nor to let her do so.

To be continued… Come back soon to read the next chapter of this unique parent diary, using the tags to help you.

Visit the Hampshire EMTAS website for information and guidance on how to help settle a newly arrived pupil into school.

Pairing up new arrivals with pupils who speak the same language is a good way of alleviating the anxiety of the first few weeks when everything is new, different and sometimes overwhelming. Coping in an unknown language for academic as well as social purposes over long periods of time is extremely tiring.

Newly-arrived pupils need appropriate support as they adjust to their new surroundings and routines and it makes complete sense to allow pupils to learn school routines, meet new friends and settle in at school through a language that is familiar to them. It also makes sense for pupils to engage with their learning through first-language, as anything that is cognitively challenging can then be discussed more easily and in greater depth. In short, first-language is an asset and a useful tool for learning as well as for settling in – so much so that for some, it might appear reasonable to ask bilingual pupils to interpret in all sorts of situations.

The use of children and young people as interpreters

There is limited guidance on the use of children and young people as interpreters at school and limited research around this theme, especially in the UK. What we do know is that ‘child interpreting’ is an underestimated role. Somehow, children and young people rarely have any concept of what a fantastic skill they have. What we also know is that whilst some feel extremely proud of being able to support their family through interpreting, others may perceive this to be a burden.

This is the case particularly when children and young people are requested to interpret in situations where the language and concepts involved are too difficult or unfamiliar for them to understand and relay accurately. Research also suggests that in the context of lessons, child interpreters are comfortable interpreting for routine tasks that require everyday language but struggle to interpret for new concepts where the language is more demanding due to its academic nature.

So, is it fair to ask Kacper to translate photosynthesis into Polish for us?

Some pupils who have been to school in their home country and studied this subject already may be quite confident to do so. However, more often than not learners will rely on English keywords when discussing their work in first language. Therefore, we should be careful not to assume that children and young people can cope with the language demands of the classroom to such a degree than they can replace bilingual assistants, professional interpreters and good quality, EAL-friendly teaching and learning. This is not to say that Kacper can’t help. In fact, he would benefit from his school setting up a peer-buddying programme such as the award-winning Young Interpreter Scheme®.

Young Interpreter Scheme

The Young Interpreter Scheme® is a successful, low-cost, self-sufficient framework consisting of training for learners aged 5-16, designed to skill them up to help new arrivals with English as an Additional Language feel welcome and settled in their new school environment. It supports pupils by giving them the tools to use their qualities and language skills effectively to help other pupils. The scheme also upskills school practitioners in charge of delivering the scheme thanks to guidance informed by research, self-explanatory resources and interactive e-learning material. These resources enable Young Interpreter Coordinators to train pupils and guide them in their role whilst preventing them from being used in inappropriate scenarios. The Young Interpreter Scheme® provides very clear guidance on the situations where pupils should be operating. For example, showing non-English speaking visitors around the school, buddying with new arrivals during breaks and lunchtimes and demonstrating routines, not interpreting for concepts in the classroom.

The Young Interpreter Scheme® gives children and young people who, like Kacper, interpret on an ad hoc basis, real recognition of their skills through a high-profile role defined, by clear parameters which ensure their safeguarding. Through this, the scheme also sends positive messages about multilingualism. This impacts pupils’ sense of identity and belonging at school, their relationships with pupils from other language groups as well as their leadership skills. The Young Interpreter Scheme® also provides a stepping stone to pupils who may like to consider interpreting as a career in the future.

To find out about how your school can set up the Young Interpreter Scheme®, visit the Hampshire EMTAS website and Moodle or head to Twitter and Facebook.

Astrid Dinneen is co-ordinator of the Young Interpreter Scheme.

Article first published in April 2017 by ATL https://www.atl.org.uk/latest/kacper-what%E2%80%99s-photosynthesis-polish