Site blog

By Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisors Lisa Kalim and Astrid Dinneen

In the academic year 2021-22, Hampshire EMTAS saw its highest ever increase of referrals for asylum seekers and refugees with over 300 referrals made by schools. The majority were for children and young people from Afghanistan and Ukraine. The former was caused by the Taliban reclaiming power in Afghanistan in summer 2021 and the latter by the war in Ukraine starting in spring 2022.

In order to better support these children and families, Hampshire EMTAS welcomed new Bilingual Assistants on to the team covering Pashto, Dari, Farsi and Ukrainian languages. The Teacher Team caught up with these new colleagues to find out more about the backgrounds of these children. This highlighted many areas which school practitioners will find useful when settling and supporting their new arrivals. Lisa Kalim and Astrid Dinneen summarise these key areas before concluding with a list of recommendations and further resources.

Climate

In general, Afghanistan has extremely cold winters and hot summers, although there are regional variations. Most of the precipitation falls between December and April, with the summer months being very dry apart from in the south-eastern region. Afghan children may not consider our winters to be particularly cold or our summers particularly hot and may for example not feel the need to wear a coat in winter or short sleeves in summer.

In contrast, Ukraine has a temperate climate, with winters in the west being considerably milder than in the east. In summer, the east often has higher temperatures than the west. Summers are much wetter than winters with June and July being the wettest months. The west of Ukraine tends to have more rainfall than the east.

Geography

Afghanistan is a landlocked country in south-central Asia. It borders Pakistan to the east and south, Iran to the west, and the states of Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan to the north. It also has a short border with China in the extreme north-east. It covers an area more than twice the size of the UK. Afghanistan is divided into 34 provinces, each of which is sub-divided into 421 districts for administrative purposes. There are extensive mountainous areas, as well as high plateaus and plains. Mountains cover about three-quarters of the land area, with deserts in the south-west and north. The people of Afghanistan mainly live in rural areas in the fertile river valleys between the mountains, although the desert areas of the southwest are also becoming more populated. About 4.5 million people live in the capital, Kabul, in the east of the country.

Ukraine is located in eastern Europe and has borders with Belarus to the north, Russia to the east, Moldova and Romania to the south-west and Hungary, Slovakia and Poland to the west. In the south it has over 1,700 miles of coastline along the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea. It also covers an area more than twice the size of the UK but is slightly smaller than Afghanistan. Ukraine is a largely flat, relatively low-lying country consisting of plains with mountainous areas only in small areas near its southern and western borders. The majority of people live in urban areas in Ukraine with rural areas being much less densely populated. The east and west of the country have urban areas with higher populations, together with the cities of Kyiv in the north and Odessa in the south.

Languages

More than 30 languages are spoken in Afghanistan. Many Afghans are bilingual or multilingual. There are two official languages, Dari (also known as Farsi or Persian) and Pashto. Dari is more widely spoken than Pashto, with over 70% of the population speaking it either as a first or second language. It can be heard mainly in the central, northern, and western regions of the country. It is considered to be the language of trade, it is used by the government, its administration and mass media outlets. However, it is estimated that less than 50% of Dari speakers are literate. The primary ethnic groups that speak Dari as a first language include Tajiks, Hazaras, and Aymaqs.

Around 40% of the population are first language Pashto speakers, with a further 28% speaking it as an additional language. It can be heard predominantly in urban areas located in the south, southwest, and eastern parts of the country. Pashto is used for oral traditions such as storytelling as a high proportion of Pashto speakers are not literate in the language. Although spoken by people of various ethnic descents, Pashto is the native language of the Pashtuns, the majority ethnic group.

There are also five regional languages - Hazaragi, Uzbek, Turkmen, Balochi, and Pashayi. Hazaragi is a dialect of Dari. Additionally, there are around 30 other languages spoken by minority groups in Afghanistan including Pamiri, Arabic and Balochi.

There are at least 20 languages spoken in Ukraine. The most widely spoken is Ukrainian which is the country’s official language. Russian is spoken as a first language by approximately 30% of the population, mainly in the east near the border with Russia and in the south in Crimea. Generally, Russian speakers are more likely to live in cities, and are not found in large numbers in rural areas. Many first language Ukrainian speakers will also speak Russian as a second language. However, recently the Russian language has become a very sensitive issue for Ukrainians and now many Ukrainians do not want to use Russian at all. Other minority languages spoken in Ukraine include Romanian, Crimean Tatar, Bulgarian, Hungarian, Armenian, Belarusian and Romani.

School starting age

School starting age in both Afghanistan and Ukraine is much later than in the UK. Typically, Afghan children will start school at the age of 7. Many new arrivals into Hampshire will have attended school however many were not able to attend due to factors such as having to work to support their family, school being too far from their home, fears of terrorist attacks on schools, gender and of course COVID. As a result, the formal education of many children is fragmented or minimal. This can make it harder for these children to settle in school in the UK as many are not used to attending school regularly. When attending school in Afghanistan, children would attend half a day (about 3 ½ hours a day) hence attending a full school day in the UK would be very tiring for many new arrivals initially.

In Ukraine, parents will send their children to school between the age of 6 and 7. Until then, children will typically attend nursery where the curriculum is play based and where children still nap in the afternoon. This means that these children will find it hard to complete a full day in Year R and Year 1 due to tiredness as they are used to sleeping in the middle of the day. Additionally, it is common for children to go to bed much later than is usual in the UK ie between 22.00 and 23.00. This can also contribute to tiredness and settling in issues including behaviour problems. In primary school the academic part of the day usually finishes at around 1 pm and children attend clubs in the afternoon.

Attendance

In Afghanistan children may be accompanied to school by family members or neighbours in the early days of the academic year and they will usually walk to and from school without an adult for the rest of the year. Some children may choose not to attend and have a day out instead. Parents may not find out about their children missing school because absences are not routinely reported, particularly in state schools. In private schools however children have a home-school diary which supports communication between home and settings and any issues such as lateness, absences, lack of homework etc. are reported in writing.

In Ukraine, expectations around attendance are different from that in the UK. For example, children with a runny nose and a mild cough are considered by their families to be poorly hence they are kept away from settings for long periods of time eg a week or two. This tends to be encouraged by teachers in Ukraine. Similarly, parents in Ukraine will often take their children out of school to go on holiday or for an extended weekend away.

It may be necessary for school practitioners to have conversations with parents about expectations and the law around attendance in the UK and the requirement to let the school know if children are going to be absent.

School facilities

In both Afghanistan and Ukraine, facilities depend on whether schools are state or private and on whether they are located in a city or a remote village.

In Afghanistan, girls and boys are educated separately in state schools. However in private schools they are taught together. Class sizes in Afghanistan tend to be very large. Facilities in private schools may include buildings with classrooms and sometimes IT and Science equipment whereas in rural areas classes may take place outside as there may not be a building (it might not exist or may have been destroyed). State and private secondary schools are now closed for girls since the Taliban took over in Summer 2021.

In Ukraine there are also regional disparities affecting school facilities as well as differences between private and public sectors. Facilities eg interactive whiteboards may also depend on donations from families. Class sizes are similar to those in the UK.

Teaching and learning

In Afghanistan, children wear a uniform at school. Dari and Pashto are taught in both private and state schools together with Maths, Science, Geography, History and Art. English is taught from Year 4 in state schools and from Year 1 in private schools. IT is taught where facilities allow – sometimes through textbooks, sometimes through practical work. Since the Taliban came back to power there is more of a focus on religious studies than other subjects. Children in Afghanistan are usually taught from the front and are not expected to speak to each other or to work collaboratively, just copy from the board. When children deviate from this, corporal punishment is used to discipline them.

In Ukraine the range of subjects is similar to that offered in the UK. The language of instruction is Ukrainian across the whole country and most pupils, including Russian speakers, use Ukrainian for academic purposes. Russian is not taught in schools and is not part of the curriculum. Often even Russian speaking children are not literate in Russian. Younger children may know only the basics. Older children may be more confident with reading and writing in Russian however this is usually because they have taught themselves or learnt with their parents. Children do not wear a uniform. The teaching style in state schools is traditional with children being expected to sit passively and not move around the classroom. This means that new arrivals in the UK will have to adjust to a more active and collaborative approach to learning. In fact, newly arrived Ukrainian children sometimes report that they cannot distinguish the difference between lessons and break times in the UK.

In Ukraine pupils are used to receiving plenty of homework daily and families – usually mothers – tend to spend large amounts of time supporting their children with this every day. Outside of school families will commonly also employ private tutors. Families arriving in the UK have reported their surprise at how little homework their children receive in comparison. They also report not having a good grasp of how well their children are doing here because of the differences in grading work completed at school and at home. Homework is also very important in Afghanistan and children receive it daily.

In Ukraine, children would not be expected to play outside when it rains. In fact, settings should be aware that water play – even in the summer months – is not a well-accepted learning activity because the children may get wet. Similarly, sitting on the floor is not acceptable in Ukraine - particularly for girls.

In both Afghanistan and Ukraine children are required to pass assessments in order to progress to the next year group. In practice it is rare for Ukrainian children not to progress but it is relatively common in Afghanistan.

Extra-curricular activities

In Afghanistan children may attend private language centres to learn English outside of school. They may also attend taekwondo or karate clubs as well as private art courses. Some children work part-time to support their families however many families prefer to live modestly to be able to afford extra-curricular activities for their children. Football and cricket are very popular sports in Afghanistan.

Music schools are popular in Ukraine and it is usual for children to attend up to three times a week. Many children will have brought their musical instruments to the UK to continue practising. Sports such as athletics and gymnastics are also very popular and clubs are attended just as often. Children’s assiduity means their skills can surpass that of their UK peers. Settings should make every effort to find out about children’s interests and signpost ways for them to continue developing those skills in or outside of school.

SEND

Children with SEND do not usually attend school in Afghanistan, particularly in rural areas. Instead, it is likely that they would be kept at home. There is very little educational provision available in Afghanistan for children with SEND at present, but this is beginning to change. There are a few schools that specialise in children with SEND in the larger cities, but these are mostly private and so parents would need to be able to afford the fees for their children to attend. Kabul has the country’s only school for visually impaired children which is government funded and there are also schools for hearing impaired children in Kabul and Jalalabad. Additionally, there are other small schools in Kabul catering for children with a wide range of SEND, some of which do not charge fees as they are funded by charitable donations. For those children with SEND who are able to attend standard schools, no additional support is available. These children will not be able to progress to higher year groups if they fail the end of year exams and so may have to repeat a year several times. Many of these children will eventually drop out of school as a result.

In contrast with Afghanistan, children with SEND in Ukraine do usually attend school. In the past, these children were educated away from the mainstream in either special schools for those with SEND, including boarding schools, or in separate classes held in a mainstream school with no interaction with other children without SEND. However, although many children still attend segregated provision, Ukraine is now moving towards an inclusive approach where children with SEND are given the opportunity to attend mainstream schools. This means that many children with SEND now attend standard classes with their peers. Specialist centres conduct assessments of SEND and decide upon the most appropriate form of education for the child in consultation with the parents. Additional support is provided as needed, eg through the provision of Teaching Assistants.

In both Afghanistan and Ukraine SEND can be a sensitive subject for parents with some feeling a sense of stigma or shame around having a child with SEND. Therefore, it is important to be mindful of this possibility when discussing the subject of SEND with parents.

Relationship and Sex Education (RSE)

In Afghanistan children do not learn about sex and relationships at school. In Year 10, pupils may learn about anatomy and how babies are conceived as part of the Biology curriculum but this input excludes girls who do not attend secondary school. They learn about periods at home from their mothers, older sisters or friends and the quality of information is variable. Families may respond differently when informed about the RSE element of the school curriculum in the UK. Some may be happy for their children to receive well-informed advice at school whereas others are more reticent and may prefer to withdraw their children, especially in relation to the theme of same-sex relationships which are not permitted in Afghanistan. It is recommended that settings clarify the content of the RSE sessions and highlight themes such as healthy relationships with parents so they can make an informed decision based on the facts.

In Ukraine, subjects such as Health Education and Biology cover parts of sex education however relationships is not an area that is explored in detail and schools may not provide consistent guidance. Some families may not be comfortable discussing sex education with their children while others may try to do so using books and other resources.

Family and home life

Family is very important in both Ukraine and Afghanistan and it is common for children to live with their extended family, particularly their grandparents. They play a big part in the children’s lives. In fact, grandparents help so much at home that it has been noticed by UK Early Years settings that Ukrainian children can be less independent than their peers with routine tasks such as getting dressed or putting their shoes on. At the same time, it is also usual for Ukrainian parents to leave their young children alone at home to go to work and it can come as a surprise to them that in the UK parents are not expected to do this until children are much older. Similarly young children in Ukraine would usually go to the park or walk to school on their own hence it is useful for settings to be mindful and have conversations about this early on.

Families are also very close in Afghanistan. It is common for several families to live under the same roof and under the responsibility of the grandfather who is the decision-maker. Women are responsible for cleaning, cooking, and taking care of all the children. It’s not unusual for aunts and uncles to raise their nieces and nephews as their own children, which may explain why schools may welcome more than one ‘sibling’ within the same year group. To colleagues in the UK children may not strictly fall under our notion of brother or sister but for the children themselves the relationship is very strong indeed. Questions around children’s dates of birth should be asked sensitively and we must be reminded that not all will know their birth dates anyway.

For Afghan families who practise Islam the routine of the home revolves around prayer. Some families (Sunni Muslims in particular) pray 5 times a day while others (Shia Muslims) may pray 3 times a day. They wake up early for morning prayer. There is another prayer late in the evening after which families will have their dinner hence it is not unusual for children to go to bed late at around 23.00. In Ukraine, parents finish work at 18.00-19.00 to collect their children. Life starts then – families may go out and meet with friends. Children will also tend to go to bed late. Families moving to the UK from both Ukraine and Afghanistan have had to adjust to different routines and synchronise their body clocks to that of UK children who usually go to bed earlier and get up earlier too.

Food and diet is another area that families and children from Ukraine and Afghanistan have struggled with since moving to the UK. At the time of writing many families from Afghanistan are still housed in bridging hotels where they are unable to cook their own meals from fresh ingredients or at times of their choosing. Schools have also commented that many children are hungry during the day because they do not like school dinners. Instead they may bring in hard-boiled eggs and bread from the hotel breakfast buffet which is not always enough to sustain them until the end of a busy school day. In Ukraine, families will typically have a big breakfast consisting of waffles, omelettes, fruit, etc. and will usually have a late lunch consisting usually of soup followed by a main meal. Chips, pizzas and sandwiches and other foods offered at school are not considered a proper lunch.

To conclude this section on family life it is important to note that many refugee families coming to the UK have had to leave family members behind. For example, most Ukrainian children have moved here without their fathers and older brothers because they are required to fight for their country (there are some exceptions). Many Afghan children have also left members of their extended family behind and this can cause a lot of anxiety to those who are unsure about the safety of their loved ones. Families, including mothers who have moved to the UK with their children on their own, are having to cope without their usual support network. We must be reminded that for them juggling everything unaided for the first time can be stressful, particularly in a new country where systems, customs, education and much more are so unfamiliar.

Important dates

School settings should note important religious dates for which families may wish to withdraw their children (they have the right to 1 day for each festival). Schools may wish to take an interest and celebrate these dates through cards, assemblies, etc.

Afghanistan:

Independence day: 19th August

New Year’s day in Persian calendar: 21st March

Eid al-Adha: June 29th 2023

Ramadan: will start around March 23rd 2023 and last approximately 30 days

Eid al-Fitr: end of Ramadan, April 21st 2023

Further dates: Afghanistan Public Holidays 2023 - qppstudio.net

Ukraine:

7th January – Orthodox Christmas

Easter

Birthdays and name days

First Communion

Further dates: Upcoming Ukraine Public Holidays - qppstudio.net

Summing up - recommendations

Find out as much as you can about the background experiences of your new arrivals eg previous experience of school if any, literacy levels in home language(s), etc.

Use Google maps to find out where the children lived before moving to the UK. Did they live in a city or a rural area? Consider how this might have impacted access to services, education and other infrastructures. Consider also how this may have impacted their life experiences eg Afghan children will not be familiar with coasts and may for example need support to access stories and language relating to going to the beach and playing with a bucket and spade

Be aware that some Ukrainian parents may not be comfortable conversing in Russian, particularly to a person who is Russian rather than Ukrainian, even though they may be very competent in speaking Russian as a second language. Bear this in mind when planning to use an interpreter for meetings with parents – if a Ukrainian speaking interpreter is not available and you are considering using a Russian speaker instead always check with the family how they feel about using a Russian speaker before proceeding

Set up a home-school communication book to share details of topics covered at school. This helps families become aware of what their children are learning and is also an opportunity for them to discuss their learning at home in first language

Use ICTs to support communication with parents eg Google Translate, Microsoft Translator, DeepL Translate, SayHi, etc. Note some apps have audio features for some languages and not for others so check this in advance. For example, SayHi recognises speech in Ukrainian and Farsi but not in Pashto and Dari (these require the user to input text using an appropriate keyboard). When talking to parents also give a note written in English so they can get help from others to understand any key messages

Focus on pastoral care and support settling in initially

Discuss routines including bedtime

Clarify expectations regarding behaviour, attendance and punctuality

Explain what children should be able to do by themselves depending on their age eg getting dressed and what they should still be supported with eg walking to school

Be open-minded about children’s wider conception of what close family means

Provide ELSA and bereavement support where appropriate. Use interpreters where required

Talk to pupils about how they would like to observe their faith at school. Offer a space to pray

Provide Muslim children with a vegetarian or fish option. Ensure families understand that these meals are appropriate options for their children

Find out about children’s interests, skills and talents they may have developed in their country of origin eg art, sport, music, cooking, etc.

Clarify content of Relationship and Sex Education sessions

Be mindful that for some parents the subject of SEND can be sensitive

Attend training on how to best cater for the needs of refugee arrivals (see Hampshire EMTAS network meetings) https://www.hants.gov.uk/educationandlearning/emtas/training

Further reading and resources

Coming soon: more information about children speaking Pashto, Dari and Ukrainian will be added to our collection.

Many thanks to Olha Herhel, Kubra Behrooz and Sayed Kazimi for supporting the creation of this blog.

In this blog, the Hampshire EMTAS Teacher Team considers what best practice might look like in relation to catering for the needs of refugee children on roll in Hampshire Schools.

In recent months, Hampshire has hosted a number of refugee families from Afghanistan, some of whom will remain in the county permanently whilst others will eventually be found a permanent home elsewhere. The children of these refugee families are starting to be taken onto roll at schools across the county, and this has raised a number of questions as colleagues have sought advice on how best to streamline support at this vital point in the children’s lives.

First and foremost, at the point of referral to EMTAS it has become apparent that not everyone is confident when it comes to telling the difference between an asylum seeker and a refugee. To cut to the chase, the term refugee is widely used to describe displaced people all over the world but legally in the UK a person is a refugee only when the Home Office has accepted their asylum claim. While a person is waiting for a decision on their claim, he or she is called an asylum seeker. Some asylum seekers will later become refugees if their claims for asylum are successful.

The recently-arrived Afghan refugee children are here with their families and because of this they benefit from greater continuity in terms of support from their primary care-givers. Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children (UASC), on the other hand, are minors who are here on their own and therefore don’t have the support of their close families. UASC are accommodated in the care system in the UK but their status in the longer term remains in question. They will be claiming asylum, which – if they are successful – will give them indefinite leave to remain and refugee status. This will give them the right to live permanently in the UK and to pursue higher education and/or work in the UK. Check the EMTAS guidance for more detail on this point.

Moving on to talk about refugees, in many ways the needs of

refugee children are very similar to those of any other international new

arrival, hence staff in schools should, in the main, adopt the same EAL good

practice with these children as they would any others. There are, however, some additional things to

bear in mind.

Refugee children (as well as UASC) may have had to leave their country of origin suddenly, bringing with them very few of their personal belongings and leaving much behind. Because of this, some may experience a greater sense of loss than children whose move to the UK was undertaken in a more planned way. Some refugee children will have left behind members of their extended families as well as friends, favourite toys and pets (where keeping pets is part of their culture), and may be concerned for their safety or not know their whereabouts or even if they are alive. This can be compounded by having little opportunity to communicate with them to check if they’re OK. Older children are likely to be more aware of and affected by this than younger ones, and their awareness may be heightened by conversations within their household as parents talk about and begin to process the events that brought them here.

Some refugee children will have experienced unplanned interruptions to their education, especially those who have spent time in refugee camps en route to the UK or those who have travelled with their families through various countries. Lack of facilities might mean that some have missed opportunities to keep up with their learning, hence there may be gaps. The longer the gap, the more they will have missed – hardly rocket science, but something to bear in mind when thinking about reasons why a child’s reading and writing skills may not be as secure as would normally be expected. The advice with this would be to clarify each child’s education history with parents and then to consider what arrangements might be put in place to help plug any gaps – without causing them to miss even more eg through ill-timed/too many withdrawal interventions (see EMTAS Position Statement on Withdrawal Provision for learners of EAL).

For most refugee children, routine really helps. They benefit from knowing what each school day will hold, so things like visual timetables are helpful. They also benefit from being supported to quickly develop a sense of belonging in their new school. Use buddies – including trained Young Interpreters – to support them as they adjust to their new surroundings. Bear in mind that the less-structured times such as break and lunch times can be more difficult for a newly-arrived refugee child, so check that they are being included and are joining in with play with other children. Teachers may find it helpful to teach some playground games in the relative safety and calm of the classroom, with input and support from other children in their class, with the idea that these games can then transfer to the outside areas.

Support from their peers will be key to the induction and integration of a newly-arrived refugee child. Sit them with peers who can be good learning, behaviour and language role models. Try to match them with peers who are of similar cognitive ability. Remember to reward all children involved with praise where things have gone well eg if they have shown the new arrival their book or repeated an instruction or the new arrival has accepted support from a peer or tried to involve themselves in a task or whatever. With younger learners, consider using a Persona Doll to explore ways of supporting the new arrival with your class.

When it comes to accessing the curriculum, remember the benefits of using first language both to aid access and engagement and to give the child a sense of the value of the L1 skills they bring with them. Use of L1 can be a great way of involving parents too, so make sure you think of ways they can support – perhaps helping their child look up key words or using Wikipedia in other languages to research a topic. If you have a literate child in your class, encourage them to write in L1 and explore how translation tools can be used to build a dialogue with the child and give them the skills to communicate their ideas with others in accessible ways. Many translation tools have an audio component too, so even children who can’t read very well in L1 can benefit from their use in the classroom. For more information about translation tools, see ‘Use of ICT’ on the EMTAS Moodle.

The biggest issues often relate not to language barriers but to culture; there are lots of things we take for granted to be commonly understood, shared experiences which for refugee children will be new, alien. These can include experiences of teaching and learning, for instance a didactic approach wherein the teacher conveys knowledge to the empty vessels that are their charges may have been the norm in country of origin. People whose schooling embodied this sort of approach may find learning through play or learning through engaging in dialogue with others very ‘foreign’; uncomfortably new territory they need to negotiate without any prior experience on which to base their understanding or response.

Refugee children from Afghanistan will almost invariably be Muslim and this in itself raises some issues that schools will need to address. For some children, there will be issues with school uniform, with others, schools may need to rethink key texts they are using in class eg ‘The Three Little Pigs’ with younger learners or ‘Lord of the Flies’ with children in secondary phase may be problematic. For guidance on these and other issues to do with having Muslim children on roll in your school, see the comprehensive guidance from the Muslim Council of Britain (MCB), posted in an open access course on the EMTAS Moodle here.

So to some final advice on how to negotiate this unfamiliar terrain. For one, try to remember always that refugee children’s responses may at first seem strange or oppositional or even rude. This sort of thing is likely to be indicative of a cultural barrier that needs to be overcome with both parties open to moving their respective positions. To get the best results, try to be the party that is receptive to difference and willing to make the most moves to understand and accommodate. If issues arise and you’re not sure what to do, EMTAS is here to support so do get in touch with us.

By phone 03707 794222

By email emtas@hants.gov.uk

Find out more:

EMTAS’s ‘Welcome to Hampshire’ information guide for unaccompanied asylum seeking children (UASC) has been updated. By Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Lisa Kalim.

Do you have unaccompanied asylum seeking children (UASC) in

your school? If so I recommend that you

have a look here at EMTAS’s newly updated information guide for UASC and encourage your UASC to

use this useful resource, perhaps assisting them by printing a copy out for

them. This booklet was written

specifically for the young people in our schools who are UASC and aims to help

them settle into their new lives in Hampshire as smoothly as possible. It was first created over ten years ago as a

result of feedback received from UASC who had been in our school system for

several years and who shared what they wished they had known about when they

first arrived. It has been updated

regularly ever since. It seeks to provide

information on various topics that will be relevant to unaccompanied asylum

seekers including:

- what happens at each stage of the asylum process

- what their rights and responsibilities are

- housing

- education and schools/colleges/universities

- health care

- working in the UK

- sport and recreation

- how they can attempt to contact family and friends in their home country including those they have become separated from

- details of organisations that can provide support to them.

It has been written as simply as possible to allow those UASC who are already able to read in English sufficiently to access it independently, either in a printed version or via the online version on our website. For those who can understand English well but are not yet able to read it to the level required there is also an audio version here.

For those who are unable to access either the written or audio versions in English there are translations available in the three most commonly spoken languages by our UASC here in Hampshire – Arabic, Pashto and Farsi. These can be found here. Please check that your young person is able to read in the relevant language before providing them with this resource as some UASC may not have had the opportunity to learn to read or write in their country of origin due to difficulties with accessing education. EMTAS hopes to be able to provide audio versions of these translated booklets in the future, starting with Arabic, so keep an eye out on our website.

It is helpful if UASC can be given access to Welcome to

Hampshire as soon as possible after their arrival in Hampshire but even if they

have already been living here for several months or years it can still be

useful to them as they may have forgotten some of what they were told early on

or there may just have been too much information for them to take in all at

once at a stressful time. Welcome to Hampshire can be referred to by the young

person from time to time as needed, for example as they progress through the

asylum system and would like a reminder about what will happen next.

Reading Welcome to Hampshire can also be useful for staff

as it will give them an idea of the types of areas that are likely to be

important to their UASC and explains the asylum process simply. It also contains a section on useful contacts

which staff may also find helpful if working with UASC.

At the end of the booklet there is a form on which the

young people are invited to give feedback to EMTAS about Welcome to

Hampshire. This feedback is then used to

update future versions to ensure that it stays relevant and includes

information on everything that the young people feel they need. I would appreciate it if you could encourage

any UASC in your school who use the booklet in whatever format to complete it,

with assistance from a member of your school staff if needed. The young person can write in any language

they like, or their views could be scribed for them. Responses can either be posted to EMTAS’s office

in Basingstoke (address is included in Welcome to Hampshire) or sent via email

to lisa.kalim@hants.gov.uk.

I’ll end with a quote from a 16 year old UASC from Iran who

helpfully provided us with the following feedback:

‘When I first came here, I didn’t know where I should live

or what I would do. This little book

helped me to find out what I needed to know.’

Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Lisa Kalim separates fact from fiction

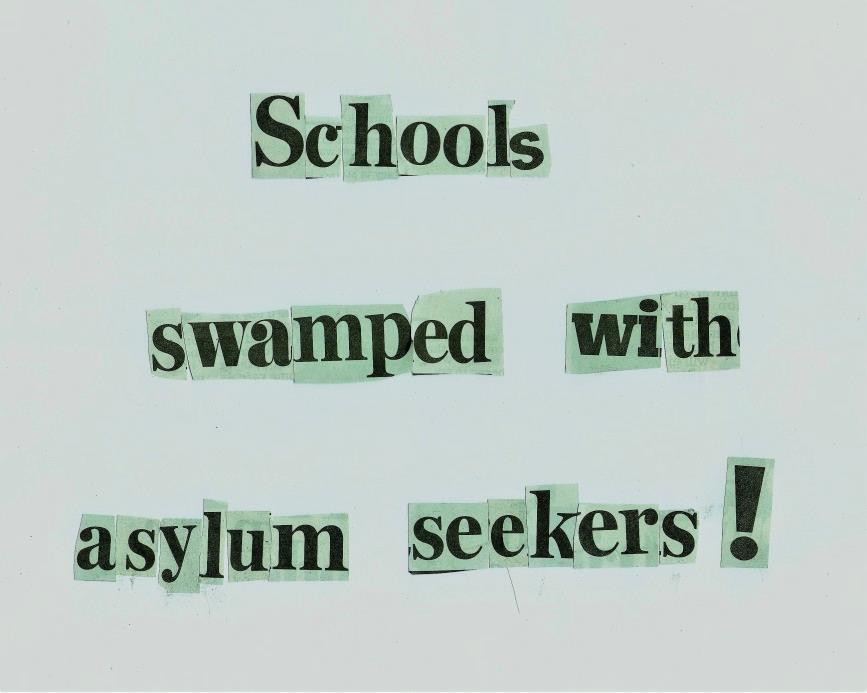

If you read and believe certain tabloid newspapers you may well have reached the conclusion that UK schools are struggling with a large influx of asylum-seeking children and young people. However, this view is not supported by the most recent data released by the Home Office in February 20181. These give the details of all asylum applications made by children in 2017 and compare the data with the previous four years. Applications from Unaccompanied Asylum Seeking Children (UASC) and those that arrived in the UK with an asylum seeking relative/guardian are included in the data so all children who were seeking asylum during this period have been considered.

How many asylum seeking children started at British schools in 2017?

Probably far fewer than you think. In 2017 a total of 2,206 children applied for asylum in their own right, down 33% from the previous year. Of these, 71% were aged 16-17, 22% were aged 14-15 and 4% were aged under 14 with a further 3% of unknown age. All are entitled to a school or college place. An additional 2,774 applied as dependents of adult asylum seekers, making a total of 4,980 children. Some of the latter were under the age of 5 years at the time of their relative/guardian’s application and so would not all need a school place straight away. When you consider that there were 8,669,085 pupils in UK schools in 2017 (DfE, 2017)2 but only 4,980 of these were newly arrived asylum seekers, it would seem clear that schools are not being swamped by asylum seekers. How can they be when one year’s worth of newly arrived asylum seeking children make up less than 0.05% of the total school population?

But don’t some areas get more than their fair share of asylum seeking pupils?

The UK operates a policy of dispersal for asylum seekers to avoid particular areas receiving much larger numbers than others. This has been in place since 2000 for adult asylum seekers and their families and whilst it is not a perfect system (it has had criticism for removing new arrivals from their extended family in the UK, for example) it has meant that any particular area should not receive more than one asylum seeker per 200 of the settled population and therefore no area should feel ‘swamped’.

For UASC, a new scheme called the National Transfer Scheme has been in place since 2016. Similarly, it limits the numbers of UASC for whom any particular Local Authority is responsible to 0.07% of its total child population. Again, this should mean that no single area should receive a larger number than it is able to manage.

Didn’t the UK take in lots of children when the Calais Jungle closed?

Between 1st October 2016 and 15th July 2017 only 769 children were permitted to move to the UK from the camps in Calais. There were 227 children from Afghanistan, 211 from Sudan, 208 from Eritrea and 89 from Ethiopia. The rest came from a variety of countries, with fewer than 10 children from each. Nowhere near enough to swamp UK schools.

Where have the rest of the children come from?

Sudan is now the country of origin for the largest number of UASC. 89% of all applications in 2017 were from the following 9 countries: Sudan (337), Eritrea (320), Vietnam (268), Albania (250), Iraq (248), Iran (213), Afghanistan (210), Ethiopia (74) and Syria (41). 89% of these children were male. For female UASC Vietnam is the most common country of origin.

For children arriving with a relative or guardian, the countries of origin are similar but with the addition of Pakistan, Bangladesh and India. Numbers from Sudan and Vietnam have increased significantly since 2016, whereas numbers from Iran and Afghanistan have decreased. In contrast to UASC, around 66% of children that arrived with a relative or guardian are female.

How many children are granted refugee status and allowed to stay in the UK?

1,998 initial decisions relating to UASC were made in 2017. Of these 1,154 (58%) were granted refugee status or another form of protection, and an additional 378 (19%) were granted of temporary leave (UASC leave). A further 23% of UASC applicants were refused. This will include those from countries where it is safe to return children to their families, as well as applicants who were determined to be over 18 following an age assessment.

For children with a parent or guardian their decisions are linked to their adult applicant’s. So, if their parent or guardian is granted refugee status, the children are too. In 2017, 68% of asylum applications (excluding UASC) were refused. Only 28% were successful and an additional 4% were granted other types of leave. The numbers being granted refugee status are the lowest that they have been in the last 5 years. The numbers of refusals increased in 2017 compared to previous years. Pakistan, Bangladesh, India and Nigeria have well above average refusal rates, whereas children from Iran, Eritrea, Sudan and Syria are most likely to be granted refugee status. Those refused can choose to appeal the decision. In 2017 only 35% of appeals were allowed, while 60% were dismissed. This means that a large proportion of the asylum seeking children arriving in our schools will not be permitted to remain in the long term.

So, are our schools being swamped with asylum seekers or not?

Based on the facts, I would say definitely not but you make up your own mind. Some schools may have more asylum seekers than others but this does not mean that they are swamped. The numbers arriving overall are falling.

References

1 Refugee Council (February 2018) Quarterly asylum statistics [online]

https://www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/assets/0004/2697/Asylum_Statistics_Feb_2018.pdf

2 Department for Education (June 2017) Schools, pupils and their characteristics: January 2017 [online] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/650547/SFR28_2017_Main_Text.pdf