Site blog

By Hampshire EMTAS Team Leader Sarah Coles

This blog is about terminology and our understanding of a specific group of children for whom English is an Additional Language: heritage language speakers.

Most practitioners who’ve spent any time at all working with

multilingual learners in schools will be familiar with the concept of the

international new arrival; children who come to the UK from overseas having

been immersed in another language from birth.

Where they are typically developing, these children’s first language

skills will be broadly similar to those of anyone who’s had a monolingual start

in life. Older learners who have been

schooled in their language (L1) in country of origin may have literacy skills

as well as oracy, whilst younger children who’ve not yet started to learn to

read and write may have age-appropriate oracy skills only. Whatever their skills in L1, it is often

shortly after their arrival to the UK that these children embark on the task of

adding English to their repertoire, hence they might be described as ‘sequential

bilinguals’; L1 first, followed by English.

Heritage language speakers are a bit different. The term ‘heritage language speaker’ is used to describe a child growing up in a society where their home language is not the same as the majority language. For example, a heritage language speaker might be a child born in the UK to Polish speaking parents. The main language in use at home might be Polish but outside of the home, they will also have exposure to English, the societally dominant language. For these children, the model of bilingualism is ‘simultaneous’; exposure to both languages from birth (or shortly after). What this means is that whilst such a child might have access to good L1 role models at home, overall their access to Polish is typically less than had they been born and raised in Poland. So they may present with different skills in L1 in comparison with a monolingual Polish-only child.

Many UK-born heritage language speakers have their first experience of being immersed for prolonged periods of time in an all-English environment at pre-school. They will, from that point onwards, rapidly develop their vocabulary in English, alongside the continuing development of L1. However, due to their more limited exposure, it would be expected that their L1 oracy skills might develop more slowly than those of a child born and raised in an essentially monolingual setting, where the main language in use in all social situations is L1.

As they reach school age, heritage language speaking children suddenly experience a dramatic increase in the amount of time they spend in social settings where English is dominant. This typically corresponds with a reduction in access to L1. Whilst in Year R, they may find opportunities to continue to use L1, for example in their spontaneous play with other children who share the heritage language; but in adult-led activities they quickly learn that English is required. Often, it is from the start of school that heritage language speakers’ L1 development plateaus whilst their English comes on in leaps and bounds. There can develop a dichotomy in terms of the words the child knows in their two languages too, with the academic vocabulary known only in English and L1 increasingly beached in informal, home-based contexts. Further, parents often notice that when addressed in L1, their child prefers to respond in English.

Thus from Year R onwards, it takes considerable effort on the part of parents to ensure their child does not lose the heritage language. This is where the Family Language Policy (FLP) comes in. FLPs are important in determining whether or not the heritage language will be successfully transmitted to the child and maintained over time, and comprise the unwritten ‘rules’ around language use in the home. In families where parents continue to use L1 at home, its transmission and maintenance tend to be more successful. But in families where parents gradually abandon L1 in favour of English, which is especially likely in families where one of the parents is a monolingual English speaker themselves, the prognosis is much bleaker. Ceding L1 in favour of English might be prompted by their children’s growing preference for the majority language, but the often unintended consequences can include those same children no longer being able to talk to their grandparents, with the chances of the heritage language surviving to the next generation, their children’s children, reduced to zero.

So what does this matter to practitioners? Well, especially in the Early Years, it is

important that schools work closely with parents if the complete loss of the

heritage language is to be avoided. These

days, ICTs gift us with lots of ways in which we can make space for children’s

L1s in Foundation Stage settings, and it’s really important that practitioners

avail themselves of these. If they do

not overtly value children’s L1s and encourage their use at school, children

will quickly learn to leave their heritage languages at the school door to wait

for home time.

To find out more about ICTs that could be used at school to promote children’s heritage languages, see

Use of ICT (hants.gov.uk)

By Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Astrid Dinneen

This term we are launching a new and innovative form of support for pupils in Years 5 and 6 and KS3/4 who are literate in their first language.

The EMTAS Study Skills Programme will be delivered to suitable pupils in withdrawal by EMTAS Bilingual Assistants. It aims to help pupils explore how they feel about their learning and their subjects and to equip them with different tools and strategies they can apply in their lessons and home learning. For example, pupils will explore and annotate texts using Microsoft Translator, learn to use Google Lens to create a glossary, have a go at using Immersive Reader to access information and much more.

The programme consists of 5 sessions of 50 minutes. Each session has been meticulously planned and resourced by the EMTAS team to offer a predictable and consistent scheme of work - regardless of the language in which it is being delivered. For instance, pupils will typically start their sessions by sharing how they have used the tools and skills covered in the previous session in class or at home. They will then consider how they feel about learning a new skill at the start of the session and revisit this again at the end. A new tool and strategy will usually be demonstrated by EMTAS staff and pupils will have the opportunity to have a go themselves using their own or school device. This will offer pupils the space to practise their new skill through the context of what they are currently learning in class. At the end of the final session, pupils will be awarded a special notebook for their hard work both during and between sessions.

The Bilingual Assistant team has worked tirelessly over the last few months to upskill themselves in delivering the programme which is now reaching the end of the pilot phase. We are ready for a full rollout after the October break and look forward to working with you to make the programme as meaningful as possible for pupils. We have reviewed our procedures and adapted our communication folder. EMTAS staff will use this document to feed back on what the pupils have focussed on during their sessions, how they have participated and what skill and IT tool they will be applying in class. This written feedback, together with continued open conversations with our staff, will give you a chance to reflect and build these very skills into your own practice, allowing pupils to draw links between the programme and their lessons. To sharpen your own IT skills and keep up to speed with the technology we’ll be using with your pupils, why not join one of our network meetings?

To find out more about the programme, please visit our website and download a flier. Please also sign up for our free network meeting on Monday 6 November at 9.30.

In this blog, the Hampshire EMTAS Teacher Team considers what best practice might look like in relation to catering for the needs of refugee children on roll in Hampshire Schools.

In recent months, Hampshire has hosted a number of refugee families from Afghanistan, some of whom will remain in the county permanently whilst others will eventually be found a permanent home elsewhere. The children of these refugee families are starting to be taken onto roll at schools across the county, and this has raised a number of questions as colleagues have sought advice on how best to streamline support at this vital point in the children’s lives.

First and foremost, at the point of referral to EMTAS it has become apparent that not everyone is confident when it comes to telling the difference between an asylum seeker and a refugee. To cut to the chase, the term refugee is widely used to describe displaced people all over the world but legally in the UK a person is a refugee only when the Home Office has accepted their asylum claim. While a person is waiting for a decision on their claim, he or she is called an asylum seeker. Some asylum seekers will later become refugees if their claims for asylum are successful.

The recently-arrived Afghan refugee children are here with their families and because of this they benefit from greater continuity in terms of support from their primary care-givers. Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children (UASC), on the other hand, are minors who are here on their own and therefore don’t have the support of their close families. UASC are accommodated in the care system in the UK but their status in the longer term remains in question. They will be claiming asylum, which – if they are successful – will give them indefinite leave to remain and refugee status. This will give them the right to live permanently in the UK and to pursue higher education and/or work in the UK. Check the EMTAS guidance for more detail on this point.

Moving on to talk about refugees, in many ways the needs of

refugee children are very similar to those of any other international new

arrival, hence staff in schools should, in the main, adopt the same EAL good

practice with these children as they would any others. There are, however, some additional things to

bear in mind.

Refugee children (as well as UASC) may have had to leave their country of origin suddenly, bringing with them very few of their personal belongings and leaving much behind. Because of this, some may experience a greater sense of loss than children whose move to the UK was undertaken in a more planned way. Some refugee children will have left behind members of their extended families as well as friends, favourite toys and pets (where keeping pets is part of their culture), and may be concerned for their safety or not know their whereabouts or even if they are alive. This can be compounded by having little opportunity to communicate with them to check if they’re OK. Older children are likely to be more aware of and affected by this than younger ones, and their awareness may be heightened by conversations within their household as parents talk about and begin to process the events that brought them here.

Some refugee children will have experienced unplanned interruptions to their education, especially those who have spent time in refugee camps en route to the UK or those who have travelled with their families through various countries. Lack of facilities might mean that some have missed opportunities to keep up with their learning, hence there may be gaps. The longer the gap, the more they will have missed – hardly rocket science, but something to bear in mind when thinking about reasons why a child’s reading and writing skills may not be as secure as would normally be expected. The advice with this would be to clarify each child’s education history with parents and then to consider what arrangements might be put in place to help plug any gaps – without causing them to miss even more eg through ill-timed/too many withdrawal interventions (see EMTAS Position Statement on Withdrawal Provision for learners of EAL).

For most refugee children, routine really helps. They benefit from knowing what each school day will hold, so things like visual timetables are helpful. They also benefit from being supported to quickly develop a sense of belonging in their new school. Use buddies – including trained Young Interpreters – to support them as they adjust to their new surroundings. Bear in mind that the less-structured times such as break and lunch times can be more difficult for a newly-arrived refugee child, so check that they are being included and are joining in with play with other children. Teachers may find it helpful to teach some playground games in the relative safety and calm of the classroom, with input and support from other children in their class, with the idea that these games can then transfer to the outside areas.

Support from their peers will be key to the induction and integration of a newly-arrived refugee child. Sit them with peers who can be good learning, behaviour and language role models. Try to match them with peers who are of similar cognitive ability. Remember to reward all children involved with praise where things have gone well eg if they have shown the new arrival their book or repeated an instruction or the new arrival has accepted support from a peer or tried to involve themselves in a task or whatever. With younger learners, consider using a Persona Doll to explore ways of supporting the new arrival with your class.

When it comes to accessing the curriculum, remember the benefits of using first language both to aid access and engagement and to give the child a sense of the value of the L1 skills they bring with them. Use of L1 can be a great way of involving parents too, so make sure you think of ways they can support – perhaps helping their child look up key words or using Wikipedia in other languages to research a topic. If you have a literate child in your class, encourage them to write in L1 and explore how translation tools can be used to build a dialogue with the child and give them the skills to communicate their ideas with others in accessible ways. Many translation tools have an audio component too, so even children who can’t read very well in L1 can benefit from their use in the classroom. For more information about translation tools, see ‘Use of ICT’ on the EMTAS Moodle.

The biggest issues often relate not to language barriers but to culture; there are lots of things we take for granted to be commonly understood, shared experiences which for refugee children will be new, alien. These can include experiences of teaching and learning, for instance a didactic approach wherein the teacher conveys knowledge to the empty vessels that are their charges may have been the norm in country of origin. People whose schooling embodied this sort of approach may find learning through play or learning through engaging in dialogue with others very ‘foreign’; uncomfortably new territory they need to negotiate without any prior experience on which to base their understanding or response.

Refugee children from Afghanistan will almost invariably be Muslim and this in itself raises some issues that schools will need to address. For some children, there will be issues with school uniform, with others, schools may need to rethink key texts they are using in class eg ‘The Three Little Pigs’ with younger learners or ‘Lord of the Flies’ with children in secondary phase may be problematic. For guidance on these and other issues to do with having Muslim children on roll in your school, see the comprehensive guidance from the Muslim Council of Britain (MCB), posted in an open access course on the EMTAS Moodle here.

So to some final advice on how to negotiate this unfamiliar terrain. For one, try to remember always that refugee children’s responses may at first seem strange or oppositional or even rude. This sort of thing is likely to be indicative of a cultural barrier that needs to be overcome with both parties open to moving their respective positions. To get the best results, try to be the party that is receptive to difference and willing to make the most moves to understand and accommodate. If issues arise and you’re not sure what to do, EMTAS is here to support so do get in touch with us.

By phone 03707 794222

By email emtas@hants.gov.uk

Find out more:

In this blog, Hampshire EMTAS Bilingual Assistant Eva Papathanassiou reviews Mantra Lingua’s Kitabu dual-language ebook Library.

I got very excited and relieved a few months ago, when I opened my work inbox and read that I was invited to have access to an application which is literally an e-book library! Excited, because as a Bilingual Assistant, I know how any first language use, tool and resource can be extremely useful and significant for supporting children who have English as an Additional Language (EAL) to engage with the curriculum. Relieved, because this rich and diverse library would be in my hands, at any place, at any time, in less than one minute, without having to travel to our main office to get a resource or having to ask my colleagues to send to me at short notice.

I will briefly present to you this tool which is available as an app (download from Google Play or App Store) as well as through a URL on laptops and computers. I will then share with you two examples of how I have used it and why I am still so enthusiastic about it.

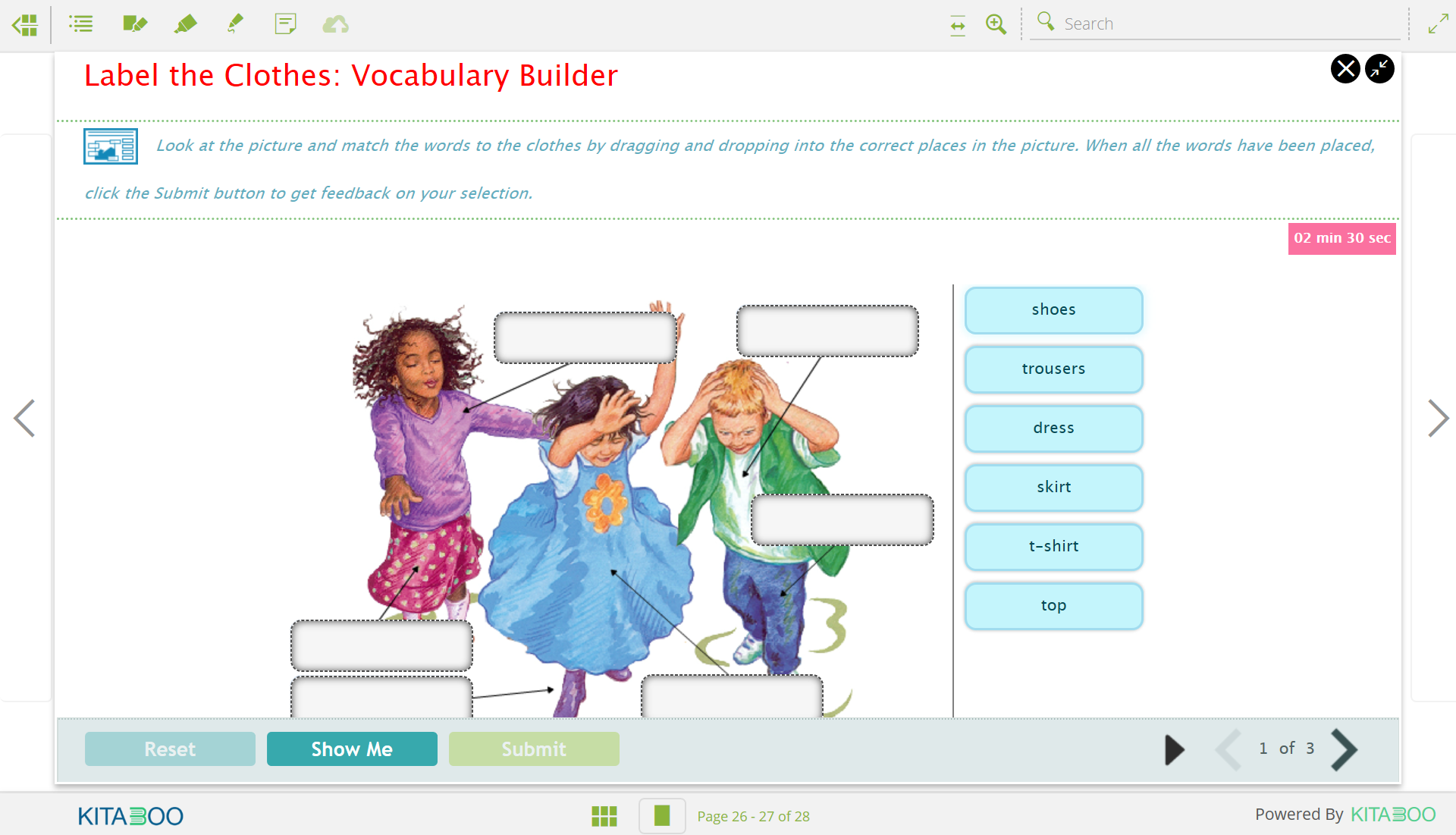

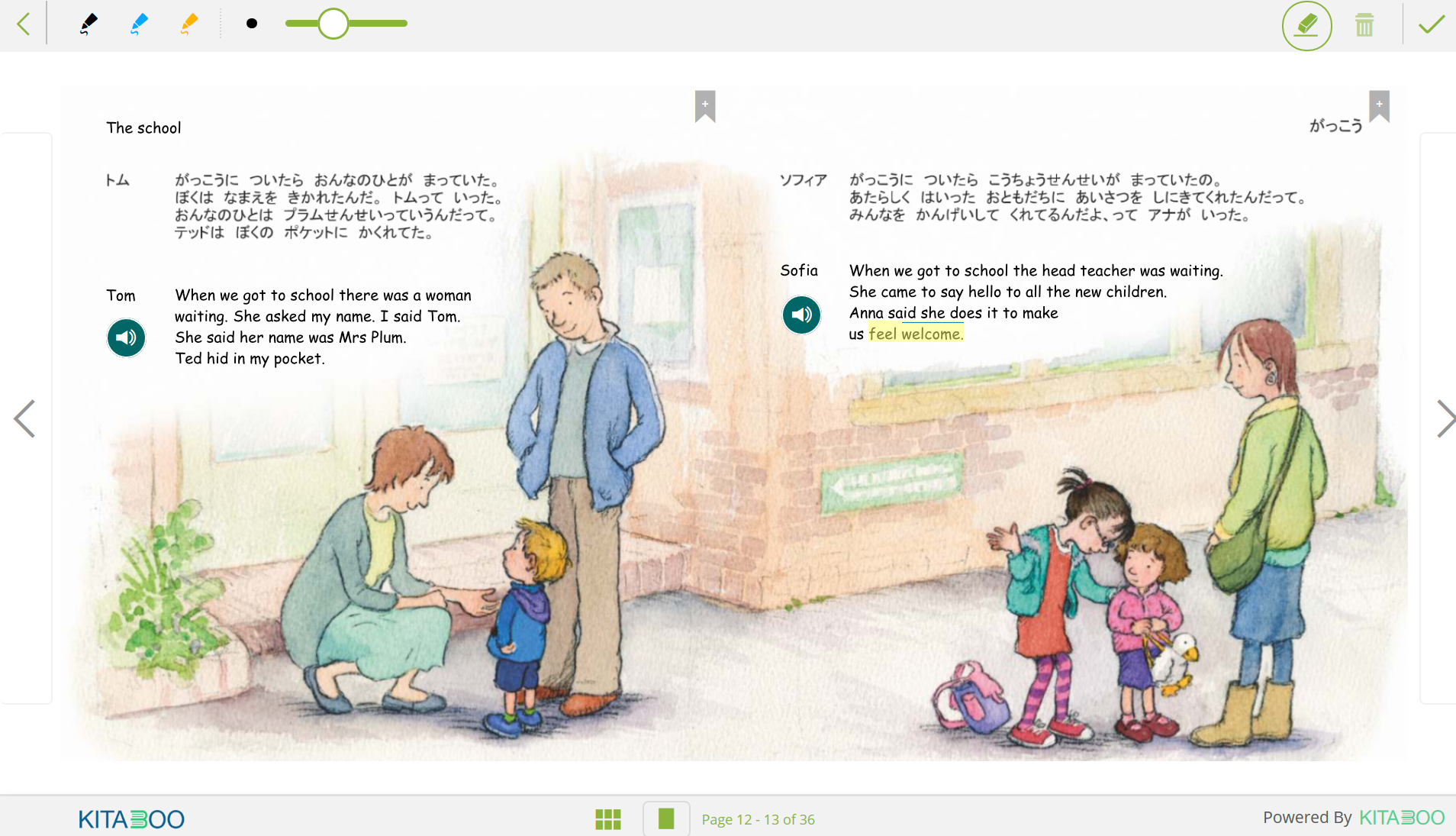

The Kitabu dual-language ebook Library by Mantra Lingua is a bilingual, interactive e-book library which gives you access to more than 550 books in 42 languages. The books are grouped by origin of language and type/genre. The majority of the books are fiction and folk stories for primary to early secondary (KS3) children. The fantastic thing about this library is that every e-book has both text and narration in two languages and different extra features. For example, you can create and share notes in any page, you can highlight a word or you can use a pen to draw, write or erase in any place in the text. You can also ‘tap around to hear the sound’ - tap around the page and hear the sounds of the illustration, making the book very vivid and appealing, especially to young children.

Most e-books contain a video of the story in English and follow on activities at the end for vocabulary and comprehension such as flash cards, labelling the parts of a picture, matching pairs, sequencing pictures and video observations matched with reading comprehension multi-choice questions. As you will read later on, I found the activities extremely useful to both EAL pupils and myself, especially for making the children feel more relaxed and confident, creating a rapport and for assessing first language literacy skills.

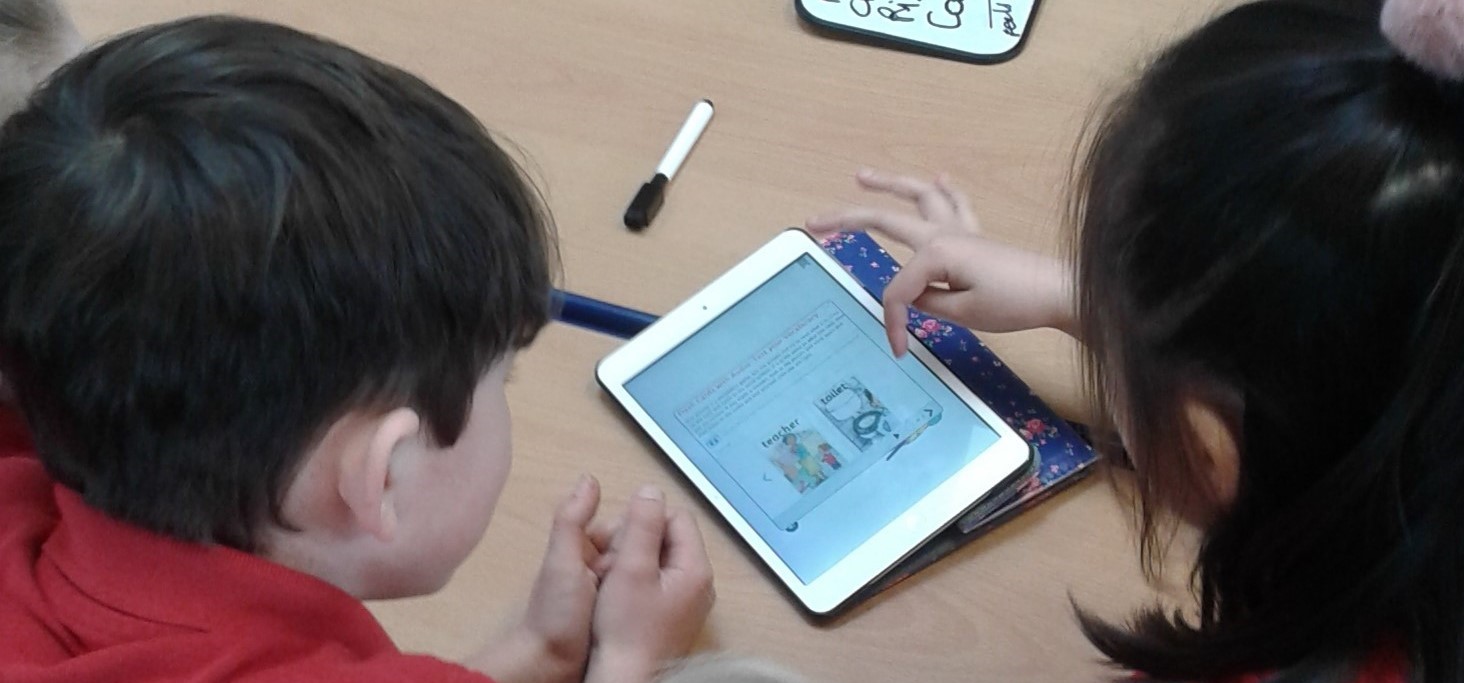

I first used the Kitabu dual-language ebook Library last autumn, when I visited a Primary School to meet and support a Romanian pupil in Year 2, Alexandru*, who had recently arrived in Hampshire. One important part of my job is to write an initial profile report of the EAL pupil by collecting important information about the child, their personality, their concerns and challenges, previous education, the level of their literacy in first language and their proficiency in English at the school starting stage (in partnership with the school teacher). Sharing the same language and culture makes the pupil’s initial profile creation a more straightforward task. However, someone who doesn’t share the child’s first language would find the process more challenging due to the lack of mutual understanding and immediate rapport that comes more naturally with someone who shares the same heritage. I don’t speak Romanian so I needed to use any tools and means available that would facilitate this task, but most importantly would enable the pupil and myself to get to know each other a little bit more and establish a bond, a relationship of trust. After a brief cooking activity with his class, it was time for me to get to know Alexandru better and assess his literacy skills. The Kitabu dual-language ebook Library came to my rescue and in two minutes, I had in front of me a selection of 8 bilingual books for Alexandru to choose from. Alexandru seemed very much at ease with the tablet and he happily took it from my hands to explore it. When he noticed the title of the books in Romanian, his face lit up; he chose the book Let’s Go to the Park/Hai să mergem în parc and we both started exploring straight away.

Alexandru tapped excitedly the different parts of the book and heard the narrative in Romanian and the different sounds of the illustration, scenes of a park full of children playing with their families. Slowly, he read some of the sentences in his first language and he heard the audio and me reading the same sentences in English, whilst he was pointing to the pictures and tapping to hear the different sounds. We moved on to the activities at the end, and we looked to the bilingual glossary with matching images from the book where we could both hear and read the words in both languages. Alexandru had the opportunity to learn some new English words, teach me some Romanian ones and correct my pronunciation and at the same time he felt happier, more relaxed and engaged. He also wrote some words in capital letters in his own language showing his writing ability, which seemed appropriate to his age and previous education. Alexandru also built his vocabulary further with different games when he labelled the parts of an image by dragging the correct word at the correct place and matching different pictures to words on the tablet and submitting his answers. This e-book enabled me to engage in an informal conversation with Alexandru, made both of us feel more at ease and get to know each other a little bit better while I had the opportunity to assess Alexandru’s first language (and partly English) listening, speaking, reading and writing skills.

A second example where I found the Kitabu dual-language ebook Library extremely beneficial was when I was asked to take over the support of a Japanese girl in Year 2 at another Primary School after one of my colleagues left our team. Hinata* had learned to write in her first language at nursery in Japan and firstly joined the school in the summer term of the previous academic year, in Year 1. The school had very successfully used Hinata’s previous skills for various writing activities and the EMTAS department had already sent a bilingual book for Hinata to read together with her classmates. Hinata appeared rather shy when she had to speak to her teacher or in front of her class and she used one word answers or gestures for communication.

During one of my visits, I was asked by Hinata’s teacher to supervise a ‘guided reading’ group activity where Hinata and three of her friends would have the opportunity to read and discuss the bilingual book, Mei Ling’s Hiccups/メイリンのしゃっくり, lent by EMTAS as a hard copy.

Hinata appeared reluctant to read out loud in Japanese but she did read each page to herself and subsequently she happily heard the rest of the group who took turns to read the text in English. Very soon Hinata appeared more relaxed and took her turn to read parts of the text in English. Everyone was impressed with her reading skills and praised her efforts. We got into a conversation about parties and Hinata was able to answer closed questions and give one-word answers, using key vocabulary from the book i.e. balloon, party, drink. Having been exposed to the Kitabu dual language ebook Library very recently, I enthusiastically searched to find any appropriate Japanese books. I was thrilled to find Mei Ling’s Hiccups as an e-book and straight away I found the follow-on vocabulary and comprehension activities. In school, Hinata together with her classmates quickly got engaged in matching pictures to words and labelling different parts of a picture. Soon Hinata appeared much more confident to demonstrate her comprehension by tapping, dragging and listening to the questions, very often volunteering her answers and at the end we went back to the book text and Hinata heard parts of the story in Japanese and read several phrases in English.

Last week, I visited the Primary School again for Hinata’s follow up visit. I was looking forward to seeing and supporting Hinata again and I remembered how much Hinata together with her classmates had enjoyed the bilingual book and its linked Kitabu activities, the first thing I did was to download another Japanese e-book from the app.

Hinata was joined by three other children and all together we went to the school library to read the new e-book, Tom and Sofia start School. Hinata was again hesitant to read in her language but she was very happy to listen to the text in Japanese, read some pages to herself and the rest of the group seemed excited to hear the story in a different language and took turns to read or hear the audio of the text in English. Very often after this activity, they asked Hinata questions like ‘is this how you say the word cool?’ repeating the last word they heard from the Japanese audio. Hinata replied by ‘yes’ or ‘no’ and she was also able to answer a few comprehension questions with one word answers with no hesitation. Afterwards, we watched the animated video of the story and we proceeded to the Video Observations follow on activity where you answer comprehension multi choice questions based on what you have just seen. Hinata’s confidence grew and very soon, she volunteered to answer the questions by choosing the correct answer on the tablet, take her turn to read small portions of the text in English together with her peers and participate in the other activities such as labelling the parts in a picture or matching pairs of images and words.

I used the Notes feature to write a comment on where and how Hinata read in the book and the children used the pen to circle different words in the e-book to demonstrate their comprehension. We highlighted more tricky words or phrases like ‘feel welcome’ and the group discussed what the phrase meant with examples. They also had the opportunity to listen to and read the definition of the word ‘welcome’ in English from an e-book. Hinata took part in all group activities contentedly and apart from learning through a new story and its key vocabulary, she was enabled to demonstrate her listening and reading comprehension and reading out loud skills confidently in front of the small group of her peers. In addition, she paid attention to the given instructions in English (read by me) or heard by the activity audio and followed what she needed to do together with her classmates, proud when she submitted a correct answer. At the end of the session, the group talked about their ‘special friends’ at home, pets or toys and Hinata told everyone that hers was a bunny.

Knowing how important it is for EAL pupils to continue using their first language in school and at home, the Kitabu dual-language ebook Library with text and audio in two languages, interactive activities and animated stories gave me an excellent opportunity to create a rapport with children who do not speak English or Greek (my own first language) and enabled me to assess their first language and English skills, through story-telling, informal chats, videos and games. Both Alexandru and Hinata felt more confident and engaged, happier to express themselves and participate, something more evident in a group setting.

The Kitabu dual-language ebook Library with its extensive bilingual library is another excellent tool for enriching children’s learning environment by use of their heritage language; something essential for confidence-boosting, self-expressing, demonstrating academic knowledge, studying more efficiently and independently and most importantly maintaining their culture and sense of identity.

*pseudonym

Find out more about Kitabu dual-language ebook Library (Mantra Lingua is offering parents of learners of EAL free access to the Kitabu dual-language ebook library until the end of August - see attachment for details)

Visit the Hampshire EMTAS website

Congratulations

to Eva who was appointed as our new Bilingual Assistant Manager since writing

her blog.

As the situation regarding the Covid-19 outbreak continues to unfold and as schools, parents and children adapt to their new ways of working the Hampshire EMTAS team is sharing how they will keep up their support.

Hampshire EMTAS is still open for business and colleagues are working hard in the background to maintain our usual level of support:

- The Specialist Teacher Advisors are working on new material and training and are still available for support and advice via email, telephone or videoconferencing (preferably on Microsoft Teams). They are keeping a close eye on the situation and will contact colleagues booked to attend network meetings with an update. Note some events may still happen virtually so do continue to book on and look into downloading Microsoft Teams.

- CPD continues to be available through our EAL e-learning, which is free to Hampshire schools. Please contact us to sign up.

- The Bilingual Assistant Team are going to produce translations of key resources for the EMTAS website. They are also able to produce translations and voice-overs in other languages for curriculum resources to be used with those children they’ve been supporting e.g. PowerPoints to be used in teaching inputs. If teachers in schools have anything like this they want adapted for their learners, please get in touch.

- The Traveller Team are working on new resources for schools and a contingency plan for Gypsy, Roma and Traveller History Month, which for communities in Hampshire is being postponed but which promises a range of fun activities including line dancing and a postcard competition.

- Our language phone lines, SEND/EAL, ELSA and GRT phonelines are still running hence Hampshire practitioners and parents can continue to phone the EMTAS main phone number to speak to a member of staff. Note a list of Hampshire EMTAS colleagues’ email addresses will be shared with Hampshire schools via a ‘school com’ hence school practitioners will also be able to contact particular members of staff directly.

- Our Resources Manager is still processing some orders e.g. for digital subscriptions to the Young Interpreter Scheme but will be unable to send resources out to schools. Our Admin team is working remotely but is still responding to calls and emails from schools.

- We are working on publishing activities for Young Interpreters to carry out from home on our Moodle (free access). Note that a decision will be made about the Basingstoke Young Interpreters Conference after the Easter break.

Finally, we are keen to continue posting blogs every other week but acknowledge our original schedule will need to be tweaked to ensure articles are pertinent to our readers in these highly unusual circumstances. As far as possible our blogs will include useful links for digital resources and advice to support you and families throughout the pandemic. Please subscribe to the blog digest to stay up to date (select EMTAS on the sign up form).

We will start here with a non-exhaustive list of suggested resources which school practitioners are encouraged to share with parents where appropriate. We would like to draw your attention particularly to the Kitabu Dual Language ebook Library. A review of this library written by Hampshire EMTAS Bilingual Assistant Eva Papathanassiou is coming very soon. In the meantime, Mantra Lingua is offering parents of learners of EAL free access to the library. Please contact us for details which you can share with your families.

List of resources

Coronavirus information in other languages

- Doctors of the World

- World Health Organisation (WHO) – choose your language in the top right-hand corner

- Translated posters for hygiene tips from New South Wales Health (Australia)

Ebook libraries

- Download eBooks, eAudiobooks and eMagazines for free from Hampshire libraries

- Ebooks and audiobooks for children currently available for free at World Book Online

- Kitabu Dual Language ebook Library (blog coming soon)

- Free streaming for children on Audible. Includes stories in six languages

- International Childrens Digital Library

Resources for parents and their children

- Free resources for Young Interpreters via the Hampshire EMTAS Moodle

- National Literacy Trust – Parent Zone

- Secondary resources for home learning with the English and Media Centre

- Free British Sign Language course for under 18s

- Free home learning resources for Secondary students from the British Library Learning

- Collaborative Learning Project - Collaborative Activities are ideal for learning at home. You collaborate to make up an activity. You collaborate to do the activity. Then you sanitise the activity and pass it on to another parent or carer

- BBC Bitesize – cross-phase and cross-curricular learning resources

- BBC Programmes categorised as learning

- #stayathomestorytime - 6pm on Instagram – a daily children’s story by Oliver Jeffers

- Jack Hartman on Youtube - maths and English with physical exercises to do

- Topmarks - resources for KS1 and KS2

- The Confident Teacher – weekly themed activities and resources

- @littlelessons20 on Twitter. Two video lessons each day suitable for primary pupils

- Kelly’s Home Centre on Facebook - live free virtual cooking classes for children aged between 6 and 14

- Cambridge Assessment – offering their ResourcePlus suite, with videos and teaching resources, for free. Secondary phase

- EAL journal – for further links of suggested websites and activities

Culture

- The Royal Opera House - programme of free online content for the culturally curious at home

- ‘A list of free, online, boredom-busting resources’ from Chatter Pack. Includes links to virtual tours of museums and galleries, links to concerts and much more

- Snow Mouse – a wintry 40-minute tale for the under-fours

Online learning platforms

- Education City - resources to support literacy, numeracy and cross curricular work (including a Learn English module)

- Learning Village – blended learning materials for EAL learners

Technology

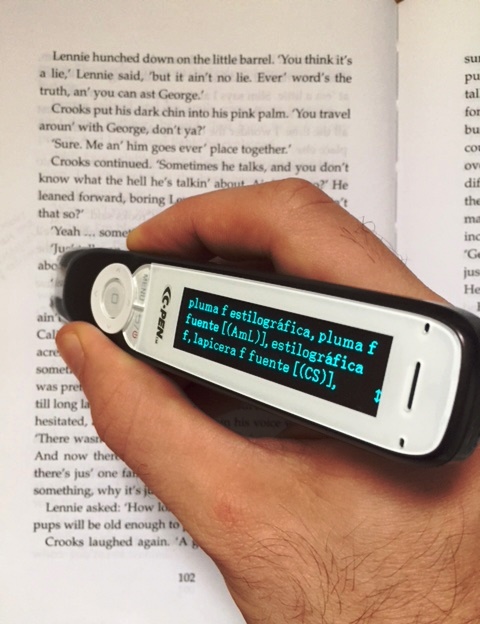

- Parents can order a free 14-day trial C-pen to be sent home in order to support their children's literacy.

Fitness and wellbeing

- Live PE workouts each morning with Joe Wicks, Body Coach, on Youtube

- PE workouts on demand with Les Mills Born to Move

CPD for school staff

- EAL elearning

- Blog

- Hampshire EMTAS website

- Bell Foundation

- Naldic

Visit the Hampshire EMTAS website

Subscribe to our Blog Digest (select EMTAS)

A review by Jamie Earnshaw, Hampshire EMTAS Teacher Adviser.

© Copyright Hampshire EMTAS 2018

As a monolingual teacher of English as an additional language, I often find myself working with students I do not share a first language with. I tend to work with students in the secondary phase of their education, the majority of whom are working on GCSEs. This often involves having to read and use texts full of more complex, academic language, usually based on more abstract concepts. I work with students from a variety of backgrounds; some fully literate in their first language, others not able to read or write but are fully competent in speaking and listening. Therefore, the way I help students to access unfamiliar texts very much depends on the individual student. The C-Pen was quite the breakthrough for me in supporting in my role.

The C-Pen is simple to use for those who are not tech savvy. Just plug it in to charge and before long, it’s ready to use. The simple menu screen makes it easy to select the target language. Then, as easy as it sounds, the tool is ready to be used. The tool works by the user highlighting the target text using the pen, either in print or on screen, and then it provides a translation of the word in the selected other language, along with a definition of the word. So, the C-Pen can be used by students working in English who want to know what particular words are, and their meaning, in their first language. Alternatively, students using first language texts to support their understanding of key concepts can use the pen to check the definition of any words in their first language they are not familiar with, keeping in mind that higher level texts may well have advanced language students have not even learnt in first language.

The pen will read out the target word and provide a definition of the word, in the two languages selected, on the screen of the pen. For those students not secure in reading, the fact that the pen reads out the target language overcomes this possible barrier. Nevertheless, this audio functionality is of course beneficial for all EAL learners; the importance of students hearing target language modelled is a fundamental principle of good practice for supporting students who are learning English as an additional language.

Often lessons are so fast paced, it can be difficult for students to use a traditional bilingual dictionary to look up individual words. With the C-Pen, it is much easier for students to look up words in fast succession as the tool works instantaneously. And, another real benefit of the pen, is it allows students to store texts and words they have looked up in files on the pen, so students can easily go back and look at any text they have looked up during their day and they can then download the files to their computer. They can therefore easily go over any texts or words, to recap their learning. They can even use the pen to audio record any ideas or thoughts they have.

The C-Pen very much encourages students to develop their independence in accessing and understanding unfamiliar texts. Students are easily able to use the pen without support from others. Nevertheless, it is of course a great tool for students to use collaboratively with others students too. Students who speak different languages, working on the same text, can use the pen to easily switch between definitions in different languages when focused on particular words/text.

Whilst it is important for students to be able to understand language at word level, it is also essential that students are able to use the language in context. The C-Pen supports with this. As well as giving a definition of the text, it also provides a sentence, in both English and the other language selected, in which the target word is used.

The C-Pen functions in English, Italian, German, Russian, Spanish and French. It really is a must have for all learners of English as additional language.

More strategies for KS3 and KS4 can be found on the Hampshire EMTAS website.

Written by Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Chris Pim

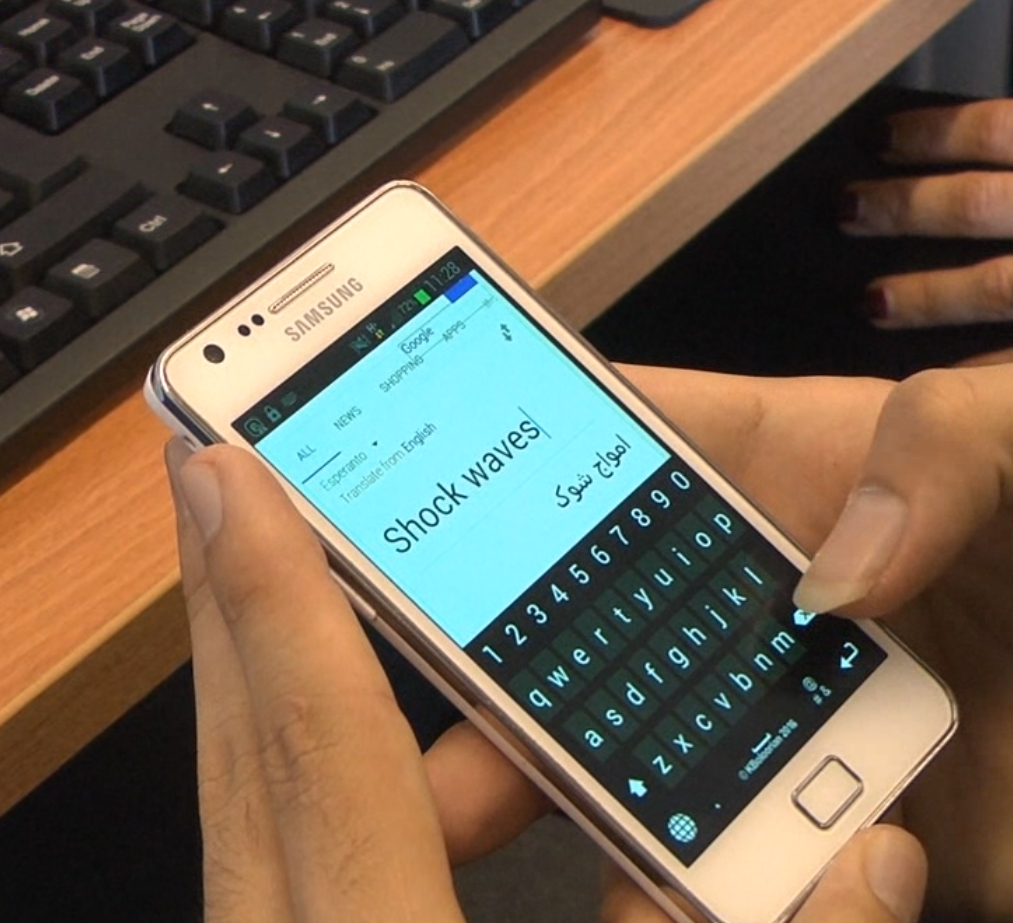

As a trainer I often find there can be a wide range of assumptions or even misconceptions about the effectiveness of digital translation tools for supporting learners of English as an additional language (EAL) and their families. Whilst there is no doubt that these tools are continuing to improve over time, they do have their limitations. So what can we say about their effectiveness - in what contexts are they useful and how can we make best use of them?

The first point that is worth mentioning is that these tools won’t be putting translators out of a job any time soon. It is certainly the case that these tools are not reliable enough for formal written translation and there are many stories, perhaps apocryphal, of nuance being completely lost because a word like ‘detention’ translates as ‘prison’. Moreover, clarification can’t easily be sought once the translated material escapes into the real world. We should also be cautious about replacing professional interpreters in situations where accuracy of face to face communication is essential, such as in formal meetings, particularly where the topic involves sophisticated or esoteric subjects and where there may be additional safeguarding issues.

So what place do these tools have for communication and curriculum-related support? It might help initially to clarify the distinction between standalone translation devices or scanning pens and other solutions that utilise the power of the internet. The former examples have been programmed with a specific set of in-built translations for vocabulary and stock phrases. These devices will be fairly accurate so long as, particularly for vocabulary, the user can pick the correct option from a range of homographs or grammatical constructs. The latter versions, online tools, will be more unpredictable but potentially much more powerful, especially when used judiciously.

Modern online tools use the immense processing power of neural networks, piecing together their output from known good translations in the target language that exist around the World Wide Web. This is how the system learns and improves and in fact certain language learning tools like Duolingo are helping by contributing to the accuracy of online translated materials. Connected devices such as phones and tablets and appropriate apps (such as SayHi and Google Translate) are beginning to transform how EAL students can benefit from using their first language skills. For example, using Google Translate a user can scan printed text with the camera on their chosen device and, as if by magic, the text will change in real time into target language. Similarly, where before the effectiveness of online translation required a user to be able to read rendered text, now a user can use the listening capability of a mobile device to register speech and read out an oral translation in a naturally synthesised accent for the target language.

This is where digital translation becomes genuinely useful. So, for ad-hoc communication, whether face-to-face or via video conferencing technologies like Skype, the conversation is mediated by the participants who can check for clarification in the moment and fall about laughing if it all goes wrong. Meaning is more important than grammatical accuracy in this context. Moreover, for more academic work users can type or talk and get instant translation which they can mediate for themselves to enhance their access to the curriculum.

Practitioners can use these technologies to communicate with students in lessons. They could translate the aim of the lesson or a key concept and also prepare resources such as bilingual keyword lists, notwithstanding the complexities of ensuring they choose the correct words. With short paragraphs, removing clauses can produce more accurate translations. Additionally, it is also possible to reverse translate to check for accuracy.

Many of these tools are free, or really low-cost, so what’s not to like? Try them and encourage your EAL learners as well. You may be surprised at the results!

written by Chris Pim, Hampshire

EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor

How to use computer games to enrich the curriculum and raise standards in reading and writing for all pupils, including more advanced learners of English as an additional language (EAL)

Introduction

Most pupils have direct experience of playing computer games, whatever their linguistic or cultural heritage. Minecraft, you may be aware, is one of the most successful games of all time. So how could you capitalise on the interest in digital gaming to engage your learners and develop approaches that can raise standards across the curriculum?

Using computer games for language learning across the curriculum – some considerations

Not all computer games are created equal – to coin a phrase. Games that are specifically designed for education, such as English language learning games, may not be that successful because pupils realise that they are no more than thinly disguised tests and don’t respond positively to them.

In an educational context the best games are immersive; the player inhabits a realistically rendered 3D world influencing a narrative- rich storyline through the actions of their character/avatar. From a learning perspective, especially for EAL pupils, professionally produced computer games contain clear graphics, authentic storylines, audio narration/music and rich texts that provide a clear context and make meaning explicit. Some also provide obvious links to the curriculum such as through historical, geographical and scientific settings and scenarios.

You also need to be aware that all marketed computer games are subject to an age rating to determine their appropriateness for children and young people (Pegi). This is an important factor in determining the type of computer game that you might choose to use with your pupils.

As you read this article you may already have ideas for suitable computer games. However you might like to consider any of the following: The Myst series, Minecraft Storymode, Syberia, The Longest Journey, Tintin - Search for the Unicorn, The Room series and Amerzone.

Curriculum opportunities

There are numerous opportunities for developing thinking, talking and writing around computer games. For example, there is obviously merit in allowing pupils to play the game in pairs/groups as the quality of discussion will benefit EAL learners as they work alongside supportive peers. There is also tremendous potential in playing parts of the game as a whole class, projecting game play onto a large digital display. One pupil plays the game and peers suggest where to look, which objects to interact with and generally help to decide on particular courses of action at major decision points. Pupils can also debate particular courses of action. This all helps to develop more academic types of language that will improve written outcomes.

Playing a computer game from start to finish won’t be possible. But the game can be moved on by playing video game walk-throughs sourced from the internet. Featured texts within the game can be used as the basis for EAL-friendly activities; vocabulary-building games, Directed Activities Related to Texts (DARTs) and collaborative writing tasks like Dictogloss.

When playing computer games it is immediately apparent how fruitful the medium is for developing writing within different text types - for example, encouraging descriptive writing around realistic settings and well-defined characters. The format also encourages learners to produce recounts of game play sessions. Finding solutions to puzzles and making progress through the game provides opportunities for instructional and explanation-based texts. Students can discuss/argue the relative strengths and weaknesses of any particular game or perhaps the appropriateness of its age-rating from the perspective of a player or parent. Pupils could also write computer game reviews.

Why not also challenge your pupils to create persuasive videos to advertise a chosen computer game? Using professionally produced video game adverts sourced from the internet you can demonstrate persuasive techniques, such as rhetorical questions, repetition, lists of three, hyperbole etc. Next, using images and video captured from their chosen game, encourage pupils to collaborate on the production of a promotional video using iMovie’s Trailer feature. You will find this activity is especially beneficial for more advanced EAL learners as it acts as an intermediate scaffold for writing persuasively.

As you can see there are many ideas for integrating computer games into the classroom to improve the reading and writing skills of your more advanced EAL learners alongside their peers. So, what’s stopping you? You won’t be disappointed with the outcomes!

To read a research case study focussed on using immersive games to improve the writing of more advanced EAL learners visit: https://eal.britishcouncil.org/eal-sector/eal-and-immersive-games