Site blog

By former EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Jess Richards

It’s one thing to be an advisor helping other people welcome new arrivals. It’s quite another when your family become the new arrivals themselves.

At the start of 2024 my husband and I relocated to Texas with our two children. To be absolutely clear, we are in a privileged position. We weren’t escaping conflict or instability, we had the support of a big corporate employer and – most significantly of all – we didn’t have a language barrier to overcome. Nonetheless, moving several thousand miles with kids has been a real education for this so-called ‘specialist’.

I am pleased to say I have seen a lot of excellent practice. My daughter arrived in Kindergarten in the middle of the school year and was literally welcomed with open arms. Teachers stood outside on her first day with signs like an airport arrivals lounge to make sure she knew where to go. They were visibly excited to meet her and make her part of the school community. We received lots of information about aspects that were completely new to us: riding the bus or joining the car lines for school pick up, buying school supplies. Despite the frequency of accepting new students from overseas it hadn’t dampened their enthusiasm. Not once did our arrival feel like an added burden in their busy schedules. School spirit and belonging wasn’t just theoretical; they were living it out every day.

There’s an infographic sometimes used in EMTAS training with concentric circles showing the concerns of newly arrived students. The outside circle is the least complex, applying to any child at a new school without the added burdens of language acquisition or forced displacement. This is the circle where my family sits. Will I make friends? Will I know where to find the toilet? Will they have food I like? These are easy to solve but often overlooked. I have a new appreciation for them now. When you’re operating in a totally different education system, the little things really matter.

What did my children find most challenging? Ironically, my six year-old daughter says it’s the language. She’s a first language English speaker in a first language English setting and yet she’s still navigating linguistic differences every day. We tried to prepare her for the obvious: restrooms, recess, trash. Others she learned by inference or plain old misunderstanding: band aids, tennis shoes, braids. Luckily she isn’t alone in a big expat community and she’s socially confident. A shy child might have found it quite tough.

The linguistic challenges for my three year-old son have been much more stark. Still early in his own English language journey, he had less context to help him piece things together. We talked about the ‘bathroom’ and the ‘restroom’ and his ‘pants’ but didn’t realise how frequently he would be asked, ‘do you need to go potty?’ Once he worked out it was ‘potty’ not ‘party’ (accents are tricky when you’re three!) he still thought it wasn’t for ’big boys’ like him. He assured them in no uncertain terms that he uses the toilet.

Our move has also taught me a lot about an aspect we sometimes overlook: cultural difference. I felt I had lived in America for nearly 40 years through my TV screen. I didn’t expect to feel so…different. Outside of my home country I don’t always know the code. What are suitable topics of conversation? Luckily we have Texan friends who will help us out and fortunately it’s usually fairly low-stakes. My daughter’s school explained that we needed a home-made post box in time for 14th February. Nonethless I didn’t realise every child in my son’s preschool class required a treat as well as a Valentine’s card. Next year we will try not to come off as the stingy Brits.

In the grand scheme of things these are minor issues. However, they serve to underline the scale of the challenge for other children who might be newly contending with language, literacy and sometimes the imprint of trauma. It’s a steep hill to climb. The very best thing we can offer in schools is empathy.

By Hampshire EMTAS Team Leader Sarah Coles and Astrid Dinneen, EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor for schools in Basingstoke & Deane

With the increase in numbers of children joining our schools from overseas with very little English, practitioners in schools are asking how best to proceed. Should they first focus on teaching the children English or is there another approach?

EAL best practice tells us that the best thing to do for such children is to include them in the full mainstream curriculum being delivered in schools via the medium of English. This can be scaffolded in various ways. The children should not be withdrawn to be taught English separately or as a prerequisite to being allowed to join their peers in regular lessons. But this immersion approach can seem an alarming response; surely the children will not be able to understand anything and will flounder and fail, people may think. So instead some opt for an ‘English first’ approach. They buy in an online English teaching app or print off worksheets for the children to learn the days of the week and the colours in English whilst their peers are learning about how plants grow or the story of The Titanic or Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

The problem with the English first approach is that far from helping, it actually slows down the children’s progress in their acquisition of English, as well as making it harder for them to feel welcomed and included in the life of their new school. Plus it adds to teachers’ workloads; now they are having to source materials for an entirely separate curriculum as well as plan for the rest of their class.

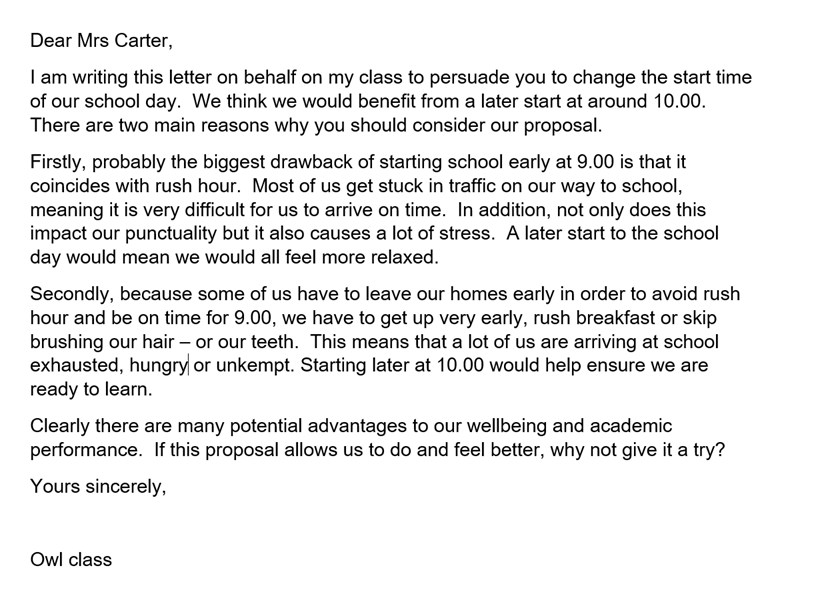

To illustrate this in more detail, consider these two

approaches for the same newly arrived child whom we shall call Hatice*. Assume Hatice

is new to English (Bell Foundation EAL Assessment Framework Band A, to those in

the know) and literate in Turkish.

Scenario 1: English first

The teacher decides to plan separate provision for Hatice, because they feel their mainstream English lesson is too challenging for Hatice’s level of English. So whilst the other children are preparing to write a letter persuading their Head Teacher to shift the start of the school day back by an hour so they start at 10.00 instead of at 9.00, Hatice will sit on her own and work through some sheets that focus on learning the English words for some colours and common classroom objects. In one example below Hatice is required to draw and colour the correct classroom object in the empty box.

It is a…

|

red |

pen.

|

|

purple |

book.

|

|

|

orange |

chair.

|

|

Fortunately, Hatice is compliant, meaning the teacher can get on with teaching the rest of the class. Hatice spends the whole morning working on these worksheets on her own. She doesn’t disrupt anyone but the teacher notices that she regularly has her head down on the desk and appears to be dozing.

At the end of a couple of weeks at school, Hatice is still very much on the periphery of things in the classroom and needs frequent reminding when she is included in instructions given by the teacher, for example when it’s time to get ready for PE or line up to go to assembly. She spends long periods of time gazing out of the window and generally seems to lack motivation and enthusiasm for anything other than home time.

There has also been a deterioration in her output and she

now very rarely completes the worksheets she is given. Where she has had a go with

tasks that require writing, her handwriting is much less tidy and it seems she is

taking increasingly less care over her work.

With regards to friendships, it seems to be still very early days and Hatice has not formed any strong relationships with her peers. She continues to spend most of her time at break and lunch times on her own.

Her teacher reflects on practice and provision so far. It has

taken a lot of time planning, resourcing and marking the worksheets for Hatice,

yet she does not seem to be making progress. He is not sure what else to do but

feels this is not a sustainable approach in the long term. He is interested in

finding out about alternatives…

Scenario 2: immersion using EAL-friendly strategies

Hatice’s teacher plans to include her in the lesson along with everyone else from the get-go. First off, before the series of lessons begins, the teacher sends Hatice home with a list of words in English to be translated into Turkish with the help of parents. He asks them to talk to Hatice about the concept of ‘persuasion’; what does the word itself mean and in what in real life scenarios might we use persuasion to get the outcome we desire? The teacher recommends the family use a translation tool like Google Translate to help them to do this:

English word/phrase |

Turkish (Türkçe) |

Persuade (someone to do something) |

ikna etmek |

We think |

düşünürüz |

Benefit |

|

Consider |

|

Because |

|

Late/later |

|

Traffic |

|

Drawback |

|

Ensure |

|

Potential |

|

The words the teacher chooses for this are drawn from a model letter which will be used in the lesson the following day. The teacher chooses to write the model himself to incorporate the language of persuasion, different persuasive techniques and ideas already suggested by the children themselves. At other times, he might have used ChatGPT to generate a model in no time.

Having diligently completed her pre-learning at home with

the help of her parents and discussed the concept of persuasion in Turkish, Hatice

is very proud to bring in a dual-language glossary she has started in her

special book. She places it on her desk

next to her pencil case. Her new buddies seem to be taking an interest in the

stickers she has stuck on her book and this adds to her feeling of pride.

She is also pleased to recognise the vocabulary she has researched and translated in a handout placed on her desk by her teacher. Everybody else is given the same handout. Hatice is intrigued and delighted to see she might not be doing different work today. Plus a Teaching Assistant approaches her holding a tablet and shows her how to scan the text to translate it into Turkish. Hatice smiles and chuckles as she reads the translation and discovers the text is a letter asking their head teacher to delay the start of the school day.

Highlighters are distributed and her buddies start a conversation. They’re highlighting parts of the letter. Hatice checks the tablet to see the translation again and tries to match the highlighted text to the translation. She starts to neatly annotate her letter in Turkish. Her teacher looks happy so she continues her annotations and adds to her dual-language glossary words such as ‘firstly’, probably’, ‘clearly’ etc. Her buddies highlighted them so Hatice thinks they must be important.

Later on, the children are to write their own letter using

features of the original. Hatice’s teacher suggests to her that she could write

her letter in Turkish. Hatice happily engages with this, writing fluently and

at length, sometimes self-correcting and adding punctuation. She writes in

paragraphs and her sentence starters seem to vary. She even attempts to

incorporate some English vocabulary eg ‘firstly’ and ‘clearly’. This reassures Hatice’s

teacher who can see she has lots of ideas and things to say. He notices Hatice

sometimes looks at her peers’ writing - both are quite happy to show her their

work – and is making use of the tablet to communicate with them using translation

apps.

What now?

Experimenting with EAL pedagogy has proved promising as it’s meant Hatice has felt included, motivated and able to meet curriculum objectives in a differentiated way. Her teacher would like to build on this by trying other EAL strategies such as substitution tables and Dictogloss, planning further opportunities for listening and speaking and continuing the use of Turkish as a tool for learning. To explore these further why not join one of our online network meetings?

EMTAS

training courses | Hampshire County Council (hants.gov.uk)

*This child's name is pronounced /hætidʒe/

By Hampshire EMTAS Polish-speaking Bilingual Assistants Magdalena Raeburn and Katarzyna Tokarska.

Have you ever felt frustrated or out of your comfort zone because of communication barrier? Have you been on holiday abroad and found it tricky to explain what you need to your local shops, hotels or restaurants?

Imagine now, how much more complex and difficult a situation of an EAL child in a UK school might be. Try to put yourself in their shoes for a while… They come to the UK not for a holiday and not out of their own choice. They have to challenge themselves against a new language, new culture and a local community as well as the unknown school set of rules and regulations.

EMTAS Empathy Training will help you understand the complexity of the challenge that the EAL child faces every day. The aims of the session are:

- To increase awareness of the challenges that EAL learners face in the UK schools

- To give an insight into Polish learners’ cultural school differences

- To share ideas of how to approach the most common challenges experienced by the EAL learners.

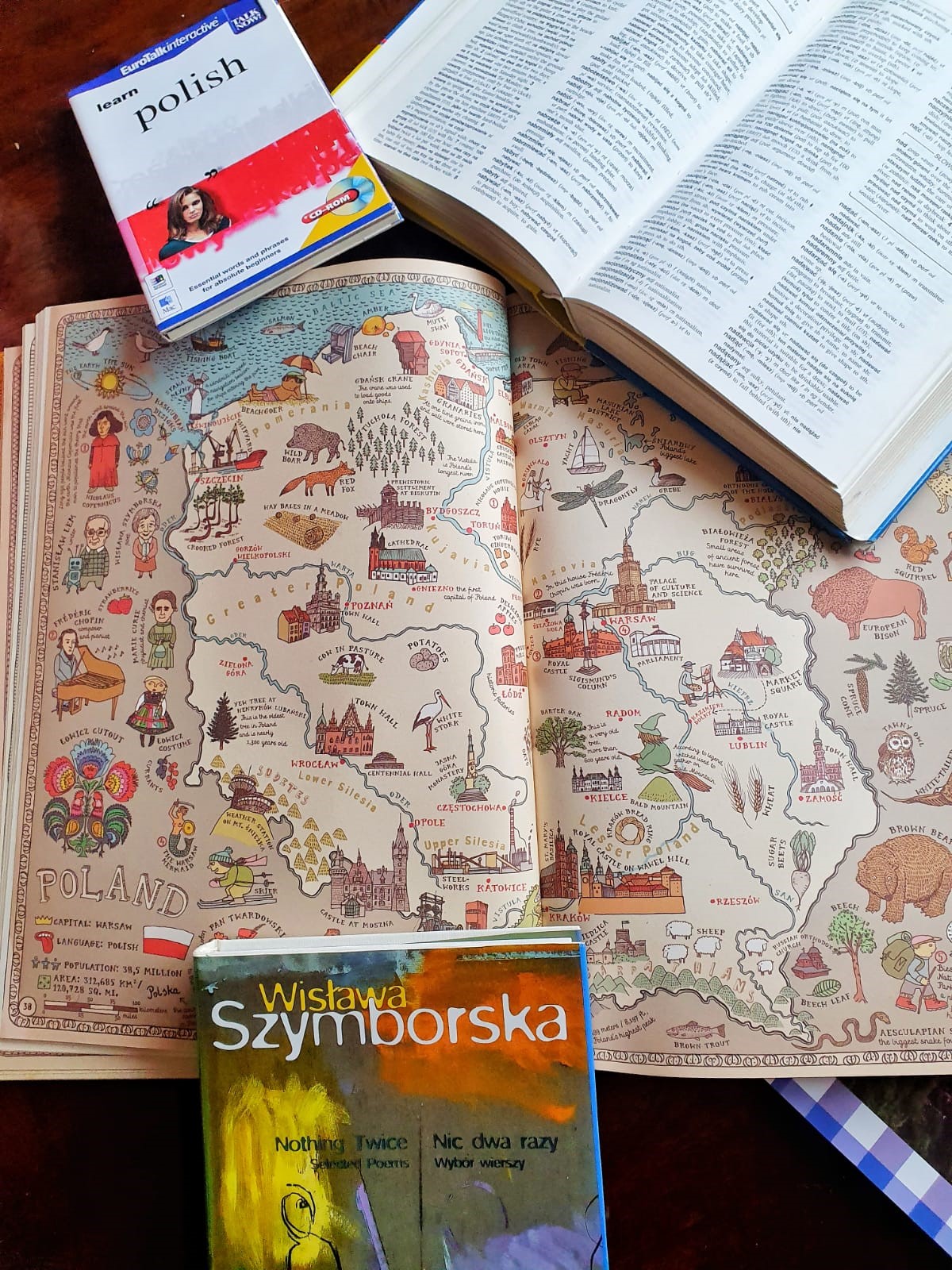

During the training you will have a chance to become an EAL learner in a Polish classroom by taking part in a practical group activity on the geography of Poland. You will be expected to understand the teacher’s presentation, participate in a variety of activities, including group work, match the pictures, read and follow instructions as well as answer questions.

Would it be ‘only’ a language barrier…?

The training participants concluded that acquiring the language is only a part of the bigger picture. Cultural traits, local history, geography and customs are also a part of learning when they are trying to integrate into the new reality.

Our ‘students’ admitted that it ‘really made (them) consider other barriers than language’.

They also discovered that the manifested child’s behaviour in the classroom might have different roots rather than the ‘obvious’ ones… One of the participants said: ‘Very useful to understand how they would/could come across as ‘naughty’ or ‘distracted’’. It was an eye-opening experience.

Our workshop attendees revealed that their ‘survival’ strategy during the session was to answer ‘yes’ to any teacher’s attempt of communication. Have you got such EAL children in your classroom? Our workshop ‘students’ said it was their technique to use to be left alone rather than having to participate in the activity they do not feel competent or confident with. Our participants also felt ‘frustrated’, ‘confused’, ‘not very clever’ and ‘wanted to avoid being asked’. They were ‘easily disengaged’, ‘embarrassed when put on the spot’, ‘wanted to give up’ and ‘finally turned off’.

The session was an opportunity to face your own emotions as well as share the strategies, resources and ideas. Some strategies could involve researching information on the EAL child’s culture, educational system as well as taking your pupil’s personal experience into account.

When the EAL children join the UK classrooms, they need more than technicality of the language and pedagogical strategies. They need our empathy at every step of their challenging, new journey.

Take part in our empathy exercise at the Basingstoke EAL network meeting on January 28th. Limited spaces available and free to Hampshire maintained schools. For enquiries, please contact Lizzie Jenner, lizzie.jenner@hants.gov.uk.

Subscribe to our Blog Digest (select EMTAS).

At a recent EMTAS teachers’ meeting we had an interesting conversation about how often we find ourselves repeating the same messages to practitioners about what good practice looks like for schools working with new arrival learners of EAL. We wondered what methods beyond face to face training and written guidance might be effective at communicating those core principles.

Of course we already have various ways of communicating good practice principles to schools in our local authority and the wider educational community, including via School Electronic Communications, Young Interpreter newsletters, our Twitter account @HampshireEMTAS, online EAL training materials and even posting on national outlets such as the EAL-Bilingual Google group.

In thinking about new ways to communicate our messages, we were inspired by Rochdale Local Authority’s brilliant video ‘Our Story’, which explores the feelings of new arrivals on their first few days at their new school. We decided to produce our own video that focused on how to settle, induct, assess and teach new arrivals to ensure they have the best possible start in the UK education system.

To produce our video, we decided on a software tool called Videoscribe (from Sparkol). For those of you unfamiliar with this technology, Videoscribe produces those videos where a hand draws images on a white canvas to the accompaniment of a narration and possibly a musical score.

The first task was to write a script to cover the key messages:

baseline assessment, with the avoidance of standardised testing

valuing linguistic and cultural diversity

building upon the skills and aptitudes of each child

effective buddying

mainstreaming teaching and learning

Having written a script, we pooled our ideas around choosing a strong metaphor through which we could visualise the main ideas (sports day theme) and any potential images that would need to be drawn. Working with a local artist we then incorporated those drawings with the narration into the Videoscribe software. The resulting video can be viewed below:

Do signpost this to colleagues, and let us know what you think.

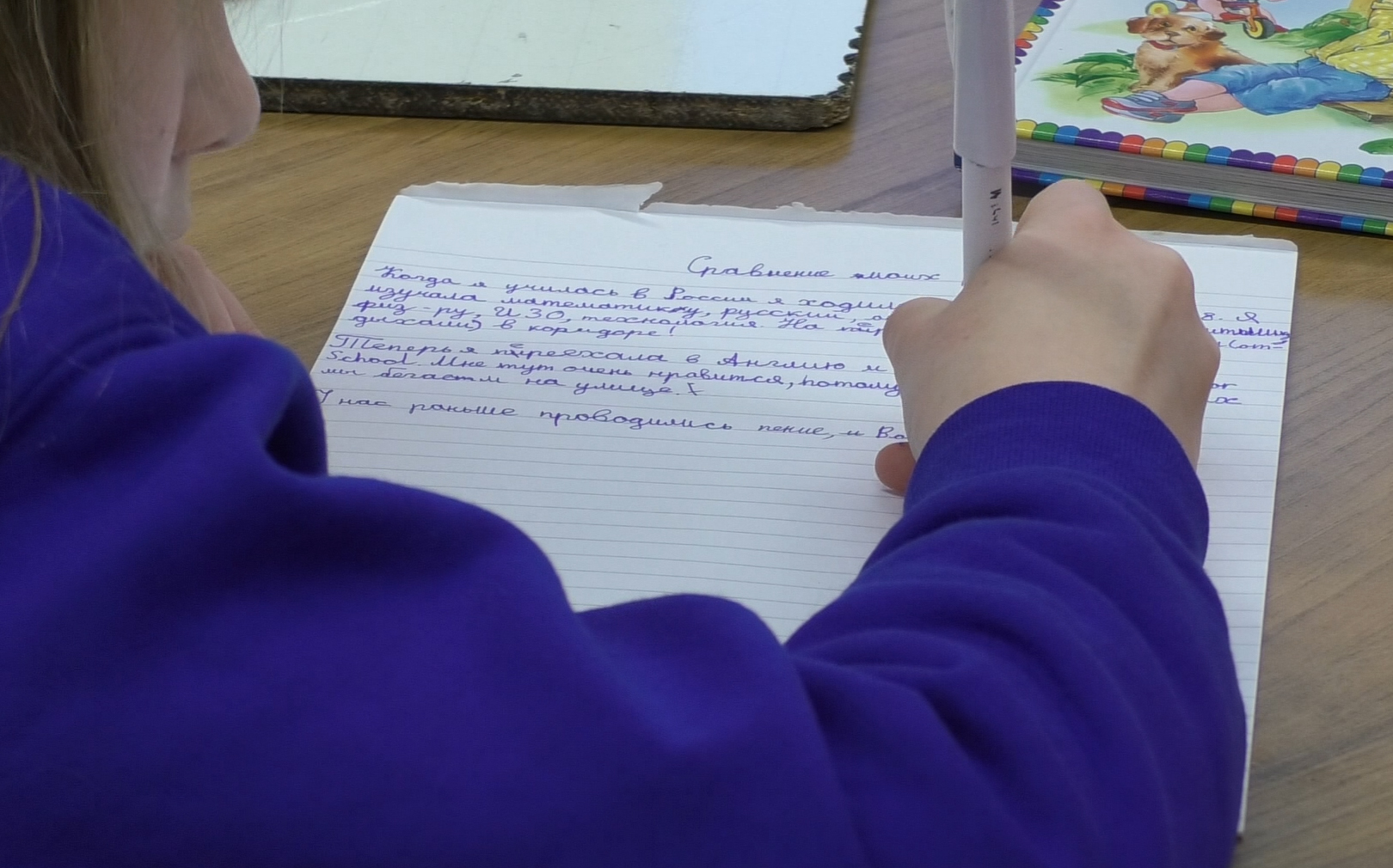

By Hampshire EMTAS Bilingual Assistant Luba Ashton

It can be very challenging for many school practitioners to start working with new EAL arrivals who have either very limited or no English language skills. In this situation, the school staff may have a lot questions and many of them can be about the pupil’s native, or first language skills:

Is the child speaking at an age appropriate level?

How proficient is this pupil in reading and writing?

Is the pupil working above or below age related expectations?

It is very important to find the answers to these basic questions sooner rather than later to start developing the pupil’s English skills with support of their first language prior knowledge and skills.

The best solution is always to invite an EMTAS bilingual assistant to carry out an assessment and get important insight in pupil's educational and cultural background. But when EMTAS are not immediately available, is there anything the school practitioners can do in the meantime, even when they do not share the pupil’s language?

It may sound surprising - but the answer is yes.

This is made possible with the help of the First Language Assessment E Learning resource, created by EMTAS. Using this E Learning tool, practitioners are given advice about how to carry out an assessment of pupil’s skills even in an unfamiliar language.

This resource will explain how to make judgement about reading proficiency; clarify comprehension, notice various features such as accent, intonation, expressing punctuation. It will also help to identify specific strengths and weaknesses in writing; handwriting, quantity, punctuation, self-correction etc.

The E Learning resource provides a practical step by step guide. It is structured into a few parts and gives very detailed instructions on how to assess listening, speaking skills and also reading and writing skills for pupils who are literate in their first language.

Other important steps explained are:

how to prepare for the first language assessment

how to guide and encourage the pupil

best practice to conduct the assessment

how to interpret the outcome of the assessment

how to use the results to further support the development of the pupil’s English skills.

The E Learning resource uses a real life case study of a new arrival Year 6 pupil, Maria. She is a native Russian speaker. The videos provide very useful guidance and enjoyable viewing. It is amazing how much you will be able to say about Maria’s Russian skills without being able to speak Russian!

The materials also provide users with a variety of interactive tools, a check list and links to other resources to support the assessment together with explanations of how to use and where to find them. It is set out to enable the practitioner to make an informed decision as to whether the pupil works at an age appropriate level and help highlight any potential issues.

Feedback from practitioners using this resource has been very positive and I am sure it will be a valuable support for the early assessment of EAL pupils. Visit Moodle for more information.

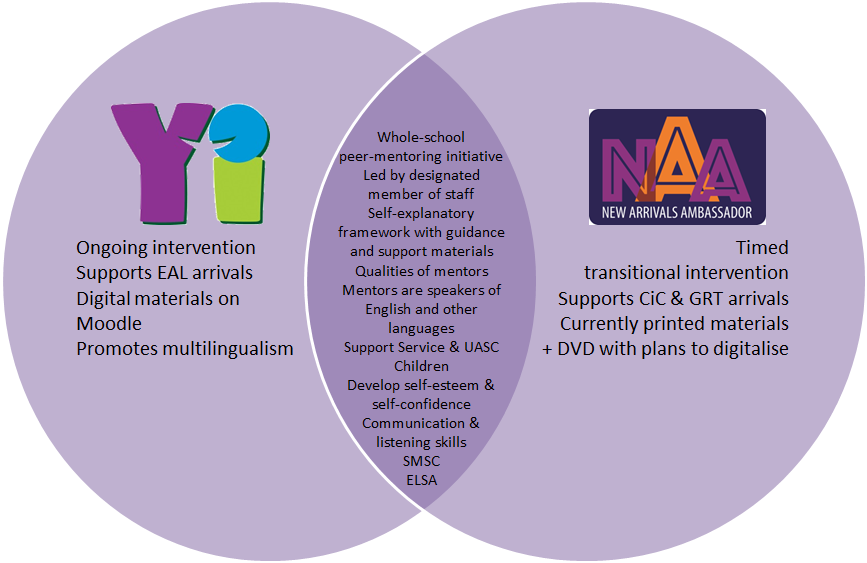

Several articles about the Young Interpreter (YI) Scheme and New Arrivals Ambassador (NAA) Scheme have already featured in the Hampshire EMTAS blog and many schools in Hampshire and across the UK are running either peer mentoring scheme - sometimes both - to support their new arrivals. Other schools have questions. Which scheme should we go for? Do they overlap? What difference is there? Our scheme managers Astrid Dinneen (YI) and Claire Barker (NAA) shed some light.

© Copyright Hampshire EMTAS 2019

Q: How did the schemes come about? Why did EMTAS decide to develop two separate schemes?

Astrid Dinneen: Back in 2004 we saw an increase of new EAL arrivals in schools after the accession of several countries to the EU. To support the well-being of these children, Hampshire EMTAS worked with school-based practitioners in four Hampshire schools to develop the Young Interpreter Scheme. The aim was to create a special role and train children/young people to become buddies and help new-to-English arrivals to feel welcome and settled. We are very proud to have won several awards since piloting the YI Scheme. Can you believe that the scheme is running in over 900 schools now?

Claire Barker: The New Arrivals Ambassador Scheme was borne out of a need by Children in Care, Traveller Children and Service Children to gain extra support when they arrived in schools at irregular times of the school year. Like the Young Interpreter Scheme, the aim was to support the well-being of these groups of children and to ensure they had a smooth transition into their new setting. The idea was to provide a short, sharp, peer mentoring programme lasting about half a term or in line with the needs of the newly arrived child. The scheme evolved after a successful piloting period that involved six schools covering all three phases.

Q: So each scheme is designed to support different groups of children, is it?

Astrid Dinneen: Yes. If your aim is to support EAL pupils whilst promoting the linguistic diversity of your school community then you may like to consider the Young Interpreter Scheme.

Claire Barker: And if your aim is to support all children joining your school at irregular times of the school year, including Children in Care, Traveller children and Service children, then you may like to consider the New Arrivals Ambassadors Scheme.

Astrid Dinneen: Of course some Service children and Children in Care (and particularly Unaccompanied Asylum Seeking Children) will also have English as an Additional Language so it's worth considering your school's needs carefully. Some schools are successfully running both schemes.

Q: How would running both schemes look?

Astrid Dinneen: An important feature of the YI and NAA schemes is that each is delivered by a designated member of school staff. In schools where both schemes are running it’s a good idea for each to be led by different people who can cater for their own scheme’s specificities and also collaborate on joint work. For example, the Young Interpreter Co-ordinator will buddy up Young Interpreters with new EAL arrivals. When a new EAL arrival also happens to be a Service child, then Young Interpreters can work alongside New Arrival Ambassadors to show them the ropes.

Another important aspect of running the Young Interpreter Scheme is that the Co-ordinator regularly meets with the Young Interpreters to guide them and keep them motivated in their role. This follow up phase could be another opportunity for joint work and there are suggested activities on the YI’s Moodle. For example, why not work together to promote both NAA and YI roles by creating a movie trailer?

In terms of pupil selection I think the qualities you would look for in Young Interpreters are similar to those you would expect from a New Arrival Ambassador. Pupils should be friendly, empathetic, welcoming and good communicators. Young Interpreters can be speakers of English only and they can be speakers of other languages too. The same could be said of the NAA, couldn’t it?

Claire Barker: It certainly could and the schemes complement each other when both are running in the same school setting. It is worth remembering that the NAA Scheme is a timed transitional intervention whereas the YI Scheme is ongoing with its support. The aim of the NAA is to develop the self-esteem and self-confidence of the newly arrived child so they are able to function independently after half a term.

I agree with Astrid that the two schemes work better when managed by different people in the school so the lines of what each scheme has to offer do not become blurred. Whilst the skills and qualities of a Young Interpreter and an Ambassador are virtually the same, the job description is very different and each has its own demands and specialist areas for the trained pupils. NAA pupils have to learn to build relationships and trust quickly as their support is delivered over a short period of time. Schools do utilise the trained Ambassadors in different ways throughout the year. Some schools use the Ambassadors to support the new intake in September and to work with classes and tutor groups throughout the academic year. Many schools use the Ambassadors alongside their School Council to represent the school on Open events like Parents’ Evenings. Some schools use their Ambassadors to support existing pupils who are struggling with their well-being and life at school. The scheme has flexibility to be adapted to the setting it is being used in.

Both schemes complement each other and pupils who are Young Interpreters and Ambassadors are highly skilled and proficient peer mentors who can offer linguistic support, well-being support and transition support. Both schemes develop self-esteem and confidence in the Young Interpreters and Ambassadors as well as in the pupils they are supporting and provide opportunities for personal growth.

Q: Where can our readers find out more?

Astrid Dinneen: You can learn more about the Young Interpreters on our website, follow us on Twitter or Facebook or read the December issue of the Young Interpreters Newsletter.

Claire Barker: There is information about the NAA on our website. You can also use the tabs below to read other blogs relating to both schemes.

Written by Hampshire EMTAS Bilingual Assistant Eva Molea, this is the first instalment in a series of blog posts focussing on the experience of parents of pupils with EAL.

March 1980

Many moons ago, when I was nearly 5, my dad decided to apply for a temporary position as plastic surgeon at Queen Victoria Hospital, in East Grinstead, and was luckily appointed. So, we packed our entire house, the useful and useless (silver cutlery included because one could never ever think of dining without one's own silver fork!), loaded our blue Alfetta and embarked on the three day trip that would change our lives.

It was early 80s, and a very exciting time to be at Queen Victoria Hospital with many other people from all over the world: Australians, French, Israeli, Egyptians, Irish, Italians, just to name a few. And, obviously, some Brits as well! It was also very exciting for us children, all attending the same primary school.

This is the background of my personal experience as an EAL child. I will not say that it was easy at the very beginning - name it the first month. The sense of deep isolation for not having a child to talk to and who understood me was overwhelming and my mum, who did not speak a single word of English, had to do everything in her powers to keep me entertained.

Then I started going to school in Year 1 and it was a blessing. My mum felt relieved (and we all know that a happy mum has happy children) as I picked up the language very quickly and made many friends, making her juggling skills no longer needed.

Besides taking me out of my linguistic isolation, the school gave me much more: thanks to the empiric approach of the British scholastic system, I developed strong observational skills and a genuine curiosity towards what I was being taught, which have been my main features through all my years at school and university. It taught me to challenge what I was learning to prove it right. It helped me develop a very rational approach to everything and the ability to analyse. Should it not be clear enough, I am still very grateful to the system. Also, the environment was amazing: massive playground with forts and a field at the back which had no boundaries. My classroom was big enough to host 30 children, plus a play-pretend corner, a big carpet, loads of toys and walls covered with pictures and resources to support our learning.

Unfortunately, my EAL experience came abruptly to its end after just one year because my dad's contract expired and we repacked all our house plus some other souvenirs, loaded again our Alfetta and headed south. Back to Naples, Southern Italy. I could have never imagined, at the time, that my own daughter would follow my steps.

February 2015

We packed our house, with all its useful and useless clutter, shipped it to the UK - how smart! - and moved in February 2015, my daughter being nearly 6 and halfway through Year 1. Strong from my personal experience, I moved quite light-heartedly. At the end of the day, how hard could it be?? This is when I learnt that every child is different, despite genetics. It also made me understand that I had always seen the whole issue of moving from a happy child's perspective, not from a sensible adult's one. I was not prepared. Not at all.

Fortunately, school started one week after we arrived, and with a school trip to the HMS Victory on day 1. What a great start! A. was very impressed and this put her in a good disposition towards her new school. As soon as her teacher introduced her to the class, a girl came and took her to line up. An unexpected act of kindness that changed one of my most dreaded days into a lovely and very informative school trip - did you know that when Admiral Nelson died he was put in a barrel of rum to be preserved for his funeral?

But the linguistic isolation struck her quite soon, so we had the before-going-to-school tantrum and the after-school one. The "I want to go back to Italy right now" desperate cry and the unintelligible sobs that showed all her frustration at not being able to function as well as she was used to in Italy.

But I was not prepared to give up. Nor to let her do so.

To be continued… Come back soon to read the next chapter of this unique parent diary, using the tags to help you.

Visit the Hampshire EMTAS website for information and guidance on how to help settle a newly arrived pupil into school.