Site blog

By Olha, EMTAS Bilingual ELSA and Sarah, ELSA at Shamblehurst Primary School

The Little Box of Big Thoughts from ‘Bear Us in Mind’

This blog explores how Bilingual ELSA (B-ELSA) support has worked at Shamblehurst Primary school in Hampshire. It brings together the perspectives of highly-experienced school-based ELSA Sarah, and EMTAS B-ELSA Olha. They collaborated to provide ELSA support to children from Ukraine. After an introductory section outlining why children from Ukraine might need ELSA support, the blog continues in the style of an interview, with questions followed by responses from these two practitioners.

Why B-ELSA support is particularly important for children from Ukraine

The need for this sort of support arises because of the array of challenging experiences many Ukrainian children will have had, related to their displacement from country of origin. For each Ukrainian child who has come to the UK as a refugee from war, their journey will be unique and may include things such as:

- sudden departure from Ukraine when the war started

- loss of their home in Ukraine

- loss of belongings

- separation from family members, who remain in Ukraine

- separation from friends

- leaving their pets behind

- not knowing for how long they will be in the UK

- adapting to living in someone else’s house with their rules and expectations (if with a host family in the UK)

- needing to adapt to life in a new language and culture

- loss of voice

- loss of choice

- loss of power and control over key aspects of their daily lives.

The

above examples all contribute to toxic stress, and come on top of other, more

common situational challenges that any child may experience, such as divorce or

changes in their family’s financial circumstances. Toxic stress can manifest itself in

physiological symptoms such as tummy aches or headaches, and in behaviours such

as withdrawal, regression to an earlier developmental stage or exerting control

through what appear to be acts of defiance or refusal, this strongly linked to the

child having lost their sense of self actualisation.

The EMTAS B-ELSA role was developed as a way of offering support with their emotional literacy to children from Ukraine, many of whom have an attendant language barrier to contend with on top of all the other worries and stresses they carry round with them daily. B-ELSAs work collaboratively with school-based ELSAs to plan, deliver and review ELSA sessions with children from Ukraine. The remainder of this blog draws on the experiences of Olha and Sarah who have successfully worked together to plan and deliver ELSA sessions to children from Ukraine.

How did you identify that your Ukrainian children needed ELSA support?

Sarah: Well, we noticed that there were things happening for the children at school that caused us to become concerned about them. Teachers were key in identifying that there may be a need in addition to learning English. This was discussed with our SENDCo and people on our Senior Leadership Team. Our Head Teacher played a role too and has been very supportive of the collaborative way of working that comes with B-ELSA involvement.

What have been the challenges in getting B-ELSA support to work?

Olha: In general, whilst I have dedicated slots in my calendar for this work, some schools have said they can’t release their ELSA to work with me, so that’s been a problem. Another issue I’ve had has been matching up calendars – mine and the school ELSA’s - to achieve consistency with the days and times of my visits. In this school, it’s been easy because the Head Teacher has been so supportive.

Sarah: To be perfectly honest, before I worked with Olha I did think in schools we are so busy so if she’s coming, it’s two adults to one child. I didn’t get it to start with - I thought ‘why don’t you just do the session on your own?’ But I totally get it now.

Olha: Yes, same here - on a personal level, when I first started B-ELSA work, I wasn’t convinced I needed to be there at all as some children from Ukraine didn’t seem to need me for the language support. I’ve changed my mind about that having had the experience of working with people like Sarah, and seeing how beneficial it is for the children.

Sarah: I think it was crucial you were here. You can give the children a real connection to home, because you give them opportunities to speak in first language. Each week, the children have looked to you for support to express particular things they’ve wanted to say; they’ve really benefited from that. Also the collaborative approach means when you stop coming, the child still has someone they know and can trust in school, someone who understands and is there for them.

How have you gone about collaboratively planning and delivering ELSA sessions?

Sarah: I’ve been really fortunate in that my school has been so open to B-ELSA support. I’ve been given two hours a week for our two Ukrainian children, which is an absolute gift; in my regular ELSA work I don’t usually get the luxury of planning time. Working with Olha, whilst I have suggested some possible activities for sessions, I’ve also valued her opinion and input. With the extra time, we’ve been able to plan sessions together, and we’ve shared our ideas.

Olha: Yes, so 15 mins ahead of the session with the child, we’ve met to recap on the previous session, and share and consider feedback from teachers about what happened for the child during the rest of the week between visits. It’s helped us tailor the sessions so we get them right for each child.

How have you figured out appropriate targets for the children you've worked with?

Sarah: One child had some friendship issues so we’ve done some work on that. They joined Year 5 and had to negotiate their place amongst friendships that were long-established within the peer group. For them, it’s been the social aspects that have been more immediately challenging, yet vital as they need to build a new support network for themselves and to gain a sense of belonging here in school.

Olha: Yes, and it’s been really helpful that Sarah knows the other children in the class. She’s brought that knowledge to the sessions – I wouldn’t have been able to do that bit on my own. For this child, we’ve also worked on boundaries, the need to respect others’ feelings, what we can do for ourselves when we’re feeling upset. So lots of work on emotional literacy.

Sarah: For another child, we decided we’d work on social skills as they’d been having difficulties following instructions in class. We introduced a second child and we played some games together. We talked about the rules of those games. The Ukrainian child said they wanted to make a booklet so we came up with the idea of making a book of rules – things we need to remember when we’re playing with friends. Each week we played a different game and we talked about the rules.

Olha: Yes, they knew we were working on that book, which was their idea. At the end, they were so proud of their book of rules and they took it to share with their class. I believe this child was more focused and engaged because we followed that project with them, their own idea.

How did you draw on the child's first language in your sessions?

Olha: I’ve collected resources in Ukrainian, Russian and English through this role. Some have come from my ELSA training with the Educational Psychology service; I especially like the ones from ‘Bear us in Mind’ – which is a charity set up to support refugee children, including those from Ukraine.

Sarah: We wanted to make sure the children understood the feelings words we were using. We used cards to talk about that. The children definitely needed Olha to be able to do this effectively. Also, after seeing some of the resources in Ukrainian that Olha brought with her, I started using translation tools myself, to create more.

For me, the language options Olha’s opened up for the children is the beauty of it – we’ll come in and have a chat about each child and go in my ELSA cupboard and choose something suitable. For example the feelings cards – we picked a few cards and we asked what’s happening in the picture. If we could add a speech bubble to the picture, what would they be saying/thinking? Because Olha’s been there, the children have been able to use whichever language they like to express their thoughts and ideas. I think this has been a real strength of it.

What has been the hardest part of working in this way?

Sarah: To be honest, at the beginning I was concerned about my waiting list children. I have lots of children with lots of needs. Prioritising the Ukrainian children did make me feel a bit bad. But a child at the top of my list was the one we chose to join some of the B-ELSA-supported sessions, which was great, really fortunate that it worked out that way.

Also, the targets from the teachers needed a bit of work to get them right for the children.

Olha: We agreed on that – it’s been really common in my experience in this role. Teachers sometimes think we have a magic wand and can solve anything and everything, but ELSA support can really only help with one thing at a time.

Sarah: Yes, when we had our Remembrance Day, one child suddenly started talking about everything they’d been through and the teachers and the other children were shocked to hear it. I think when something like that happens, people can go into panic mode.

Olha: I think this is sometimes where it doesn’t work so well in other schools – people lose confidence. They sit back and they seem to want me to do everything, which isn’t how it’s meant to work.

What's been the most useful thing to have come out of your collaboration?

Sarah: The legacy – through the work we’ve done together, the children have accessed the ELSA sessions so they’ve benefited from that. Plus now they know me really well, and they understand I’m always here for them, even if Olha’s visits have ended for the time being.

How do you achieve a sense of closure at the end of a period of ELSA support?

Sarah: Closure was really important for the children. In the end, we decided we’d give each child a card, so I modified one I had. In it, we put that Olha’s saying goodbye but the child can still come and talk to me.

Olha: Yes, a card like

this is a resource we’re now developing at EMTAS. The new cards will be printed with space to

add something personal, special to each child. All the EMTAS B-ELSAs will be able to give

them to the children they’ve worked with.

The

above conversation outlines some of the challenges associated with accessing

B-ELSA support for children from Ukraine and some of the benefits – for the

children, for their peers and for the adults around them. It illustrates how one school has added B-ELSA

support to their work with Ukrainian children and their families, developing a

healing environment in which the children can begin to recover from the trauma

they’ve experienced. To find out more

about working with refugee children and to access various free resources,

including ‘Bear us in Mind’, mentioned by Olha, see Course: Asylum

Seeker & Refugee Support (hants.gov.uk).

By Hampshire EMTAS Team Leader Sarah Coles

This blog is about terminology and our understanding of a specific group of children for whom English is an Additional Language: heritage language speakers.

Most practitioners who’ve spent any time at all working with

multilingual learners in schools will be familiar with the concept of the

international new arrival; children who come to the UK from overseas having

been immersed in another language from birth.

Where they are typically developing, these children’s first language

skills will be broadly similar to those of anyone who’s had a monolingual start

in life. Older learners who have been

schooled in their language (L1) in country of origin may have literacy skills

as well as oracy, whilst younger children who’ve not yet started to learn to

read and write may have age-appropriate oracy skills only. Whatever their skills in L1, it is often

shortly after their arrival to the UK that these children embark on the task of

adding English to their repertoire, hence they might be described as ‘sequential

bilinguals’; L1 first, followed by English.

Heritage language speakers are a bit different. The term ‘heritage language speaker’ is used to describe a child growing up in a society where their home language is not the same as the majority language. For example, a heritage language speaker might be a child born in the UK to Polish speaking parents. The main language in use at home might be Polish but outside of the home, they will also have exposure to English, the societally dominant language. For these children, the model of bilingualism is ‘simultaneous’; exposure to both languages from birth (or shortly after). What this means is that whilst such a child might have access to good L1 role models at home, overall their access to Polish is typically less than had they been born and raised in Poland. So they may present with different skills in L1 in comparison with a monolingual Polish-only child.

Many UK-born heritage language speakers have their first experience of being immersed for prolonged periods of time in an all-English environment at pre-school. They will, from that point onwards, rapidly develop their vocabulary in English, alongside the continuing development of L1. However, due to their more limited exposure, it would be expected that their L1 oracy skills might develop more slowly than those of a child born and raised in an essentially monolingual setting, where the main language in use in all social situations is L1.

As they reach school age, heritage language speaking children suddenly experience a dramatic increase in the amount of time they spend in social settings where English is dominant. This typically corresponds with a reduction in access to L1. Whilst in Year R, they may find opportunities to continue to use L1, for example in their spontaneous play with other children who share the heritage language; but in adult-led activities they quickly learn that English is required. Often, it is from the start of school that heritage language speakers’ L1 development plateaus whilst their English comes on in leaps and bounds. There can develop a dichotomy in terms of the words the child knows in their two languages too, with the academic vocabulary known only in English and L1 increasingly beached in informal, home-based contexts. Further, parents often notice that when addressed in L1, their child prefers to respond in English.

Thus from Year R onwards, it takes considerable effort on the part of parents to ensure their child does not lose the heritage language. This is where the Family Language Policy (FLP) comes in. FLPs are important in determining whether or not the heritage language will be successfully transmitted to the child and maintained over time, and comprise the unwritten ‘rules’ around language use in the home. In families where parents continue to use L1 at home, its transmission and maintenance tend to be more successful. But in families where parents gradually abandon L1 in favour of English, which is especially likely in families where one of the parents is a monolingual English speaker themselves, the prognosis is much bleaker. Ceding L1 in favour of English might be prompted by their children’s growing preference for the majority language, but the often unintended consequences can include those same children no longer being able to talk to their grandparents, with the chances of the heritage language surviving to the next generation, their children’s children, reduced to zero.

So what does this matter to practitioners? Well, especially in the Early Years, it is

important that schools work closely with parents if the complete loss of the

heritage language is to be avoided. These

days, ICTs gift us with lots of ways in which we can make space for children’s

L1s in Foundation Stage settings, and it’s really important that practitioners

avail themselves of these. If they do

not overtly value children’s L1s and encourage their use at school, children

will quickly learn to leave their heritage languages at the school door to wait

for home time.

To find out more about ICTs that could be used at school to promote children’s heritage languages, see

Use of ICT (hants.gov.uk)

By Astrid Dinneen

In a previous blog, Hampshire EMTAS Team Leader Sarah Coles and Specialist Teacher Advisor Astrid Dinneen considered ways of supporting Hatice, a Turkish-speaking pupil in Primary school working within Band A of the Bell Foundation EAL assessment framework. In this blog, we catch up with Hatice and explore EAL practice which may support her as she continues her journey towards full academic proficiency.

It’s been nearly a year since we last wrote about Hatice, a new-to-English pupil literate in Turkish who joined Year 5 in her first UK school. Avid readers of our blog will remember that her teacher chose to put in place EAL-friendly strategies to help her access the curriculum alongside her peers. For example, a home-school journal was embedded so Hatice could discover, research and translate vocabulary in advance of lessons. In addition, grouping was considered to ensure she was exposed to sophisticated speakers of English as part of a trio. Finally, another powerful way to help Hatice engage with her learning in class was to build in opportunities for her to use her first language. She used translation apps downloaded on the class iPad and wrote in Turkish to annotate handouts as well as to demonstrate her learning. This resulted in Hatice feeling included and motivated to take part in a broad and balanced curriculum.

Fast forward to now, Hatice is in Year 6. She’s working securely within Band B and she is starting to demonstrate features of Band C, particularly with listening and speaking. Hatice is a popular member of the class. She has many friends and appears very chatty on the playground. She has formed good relationships with a range of adults in the school with whom she also enjoys conversations about her activities and the things she enjoys doing at home and at school. Hatice listens carefully in class and regularly takes part during lessons to contribute to whole class discussions and collaborative group activities. Her home-school journal is still in place hence she continues to be familiar with vocabulary linked to her subjects. She also has a good go at using her keywords in her contributions. Hatice feels more confident about her speaking in English hence she is increasingly attempting to write in English. However her teacher has noticed that whilst pre-rehearsing vocabulary in advance has helped Hatice become familiar with language at single word level, she appears to need further support at sentence and whole text level.

So what now? How can her teacher build on Hatice’s success? What does EAL practice look like for learners who are beyond the early stages of learning English?

It takes a long time for pupils to acquire both informal and more academic language – anything between 5 and 10 years. To make further progress pupils will continue to need support along the way through amazing teaching and learning. In fact Hatice’s teacher should feel reassured in the knowledge that keeping going with EAL-friendly strategies rather than a decontextualised English-first approach is recommended, even after the first few months. This means persevering with practice already in place for Hatice eg inclusion in the language-rich classroom, discovering vocabulary in advance, grouping with good language role-models and using first language as a tool for learning is still recommended.

With the latter in particular, pupils embarking on Band C will still benefit from reading texts in their first language. Technology to support this continues to evolve – colleagues are now encouraging the use of Google Lens and Immersive Reader which both allow pupils to read and listen to translations instantaneously. And whilst pupils like Hatice may increasingly produce their writing in English, it is important for opportunities for first language use to still be part and parcel of teachers’ planning. For example, Hatice may be planning her writing in Turkish and later completing it in English. Encouraging the use of first language at the planning phase reduces the cognitive load, helping pupils keep momentum for the writing phase. Likewise, routinely using translation tools will undoubtedly also continue to support pupils on their journey to full academic proficiency.

New-to-English pupils tend to make rapid progress initially, particularly from Band A through to Band B. This may give us the illusion that they require little EAL support after this point. However, after this initial stage it isn’t uncommon for pupils to reach a plateau as they embark on Band C ie ‘Developing Competence’. This is usually because ‘pupils with advanced fluency in spoken English are often left without support because their conversational competence masks possible limited vocabulary for curriculum purposes’ (Cummins, 1999).

So what else can Hatice’s teacher put in place to help her choose the best ways to express herself?

Let’s explore whole class strategies that will not only benefit Hatice but also her peers, whether they are EAL or not. Her teacher may like to build on the pre-reading of keywords happening at home and plan in whole class word level activities such as bingo games, word races, dominos etc. For example, imagine that a final outcome for a whole-class topic was for pupils to write a balanced argument on whether climate change is natural or man-made. Hatice may have talked about climate change in Turkish at home and translated tier 1 and tier 2 keywords such as hemisphere, scientists, sea levels, etc. in advance. Back in class, the whole class could also focus their attention on this language. A word race for example would see pupils work in pairs or trios to find definitions hidden around their classroom and match them to the keywords. Alternatively, a bingo game would see Hatice’s teacher read out the definitions for pupils to cross off their card (bingo card generator apps can help resource this).

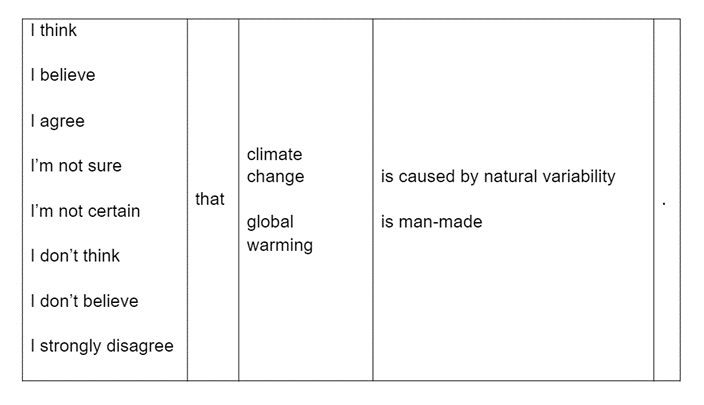

Having focussed pupils’ attention on subject specific language at word level, Hatice’s teacher could support language at sentence level. Sentence structure can be modelled and made explicit thanks to substitution tables - an extremely useful scaffolding tool to support speaking as well as writing. A substitution table is a simple frame which allows the learner to follow the correct syntax in a sentence whilst retaining autonomy over the choice of words. To continue with our theme of climate change, a substitution table could help Hatice (and others in her class) to express her views using more formal language, aided by an interactive opinion line activity:

As for modelling whole paragraphs and longer pieces, Hatice and her class could be provided opportunities for listening and speaking to prepare themselves for writing. Dictogloss lends itself well to this as a What A Good One Looks Like (WAGOLL) activity. In Dictogloss, pupils listen to a pre-prepared model text and take notes. Then they use the language they’ve heard to work with their peers (first orally then in writing) to recreate a similar piece. The end product is typically a piece of writing which includes some of the language and structures used in the model, but is not an exact replica. Dictogloss is an opportunity for pupils to hear a model that includes all the subject specific vocabulary, ideas and other things covered in class, and then to collaborate on using these same components to produce a cohesive piece of writing in keeping with the target genre.

To see what Dictogloss might look like in practice, readers can join one of our online network meetings. We will discuss the steps for Dictogloss and give a demonstration linked to our theme of climate change on January 10th and March 27th. If you cannot wait that long, why not talk to your EMTAS Teacher Advisor about whole staff training? You can also liaise with the English HIAS team to find out how EAL strategies can be woven through the English Learning Journey. For further resources, check our Guidance Library on Moodle and visit the HIAS team’s own platform.

Hatice is pronounced /hætidʒe/

By Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Astrid Dinneen

This term we are launching a new and innovative form of support for pupils in Years 5 and 6 and KS3/4 who are literate in their first language.

The EMTAS Study Skills Programme will be delivered to suitable pupils in withdrawal by EMTAS Bilingual Assistants. It aims to help pupils explore how they feel about their learning and their subjects and to equip them with different tools and strategies they can apply in their lessons and home learning. For example, pupils will explore and annotate texts using Microsoft Translator, learn to use Google Lens to create a glossary, have a go at using Immersive Reader to access information and much more.

The programme consists of 5 sessions of 50 minutes. Each session has been meticulously planned and resourced by the EMTAS team to offer a predictable and consistent scheme of work - regardless of the language in which it is being delivered. For instance, pupils will typically start their sessions by sharing how they have used the tools and skills covered in the previous session in class or at home. They will then consider how they feel about learning a new skill at the start of the session and revisit this again at the end. A new tool and strategy will usually be demonstrated by EMTAS staff and pupils will have the opportunity to have a go themselves using their own or school device. This will offer pupils the space to practise their new skill through the context of what they are currently learning in class. At the end of the final session, pupils will be awarded a special notebook for their hard work both during and between sessions.

The Bilingual Assistant team has worked tirelessly over the last few months to upskill themselves in delivering the programme which is now reaching the end of the pilot phase. We are ready for a full rollout after the October break and look forward to working with you to make the programme as meaningful as possible for pupils. We have reviewed our procedures and adapted our communication folder. EMTAS staff will use this document to feed back on what the pupils have focussed on during their sessions, how they have participated and what skill and IT tool they will be applying in class. This written feedback, together with continued open conversations with our staff, will give you a chance to reflect and build these very skills into your own practice, allowing pupils to draw links between the programme and their lessons. To sharpen your own IT skills and keep up to speed with the technology we’ll be using with your pupils, why not join one of our network meetings?

To find out more about the programme, please visit our website and download a flier. Please also sign up for our free network meeting on Monday 6 November at 9.30.

By the Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisors

In this first blog of the new academic year, the Hampshire

EMTAS Teacher team share important news and highlights. There is much to look

forward to!

Staffing

We are very pleased to welcome five new Bilingual

Assistants (BAs) to our team: Olena,

Alex, Lana, Vlad and Kevin. Olena, Alex, Lana and Vlad speak Ukrainian and

Russian (Lana speaks German too), and Kevin speaks Cantonese. Olena, Alex and Vlad will be joining Olha (who is also a Ukrainian and Russian-speaking BA)

to act as B-ELSAs: bilingual ELSAs who, thanks to government funding, will be

helping to support the emotional wellbeing of our refugees from Ukraine. We

have also had an increase in referrals from Hong Kong and so Kevin will be

joining Jenny and Catherine, our Cantonese-speaking BAs. This will help speed

up response times for BA support for our Cantonese-speaking pupils.

GCSE results

September is always an exciting time of the year as we see results pour in for the Heritage Language GCSEs. This year EMTAS supported 152 candidates with 11 different languages and our Bilingual Assistants were delighted to meet so many talented bilingual or multilingual learners. As in previous years, the student success is spectacular! Results are still coming in, but so far more than 85% of students have achieved grade 7 or above.

Naturally it will soon be time to start the process all

over again, so we are currently updating our training and processes to make

everything run even more smoothly in 2024. We are grateful to all the schools

who have given us useful feedback about their experience of EMTAS support and shared

comments from the examiners’ reports. We look forward to achieving even more

support requests for next summer when we relaunch our request form towards the

end of the autumn term.

SEND/EAL news

After many years of operation, we closed the EMTAS EAL/SEND

phoneline at the end of last academic year. However, we are still very much

here to support colleagues in schools where there are concerns about a child

for whom English is an Additional Language. Now, instead of waiting for Tuesday

afternoon, you can phone us on our main office number at any time convenient to

you during term time. A member of the team will either route your call through

to the Specialist Teacher Advisor (STA) for your district OR take details from

you so that your STA can phone you back. We hope that this will be a more

direct, faster way of accessing support where you are working with children who

are learning EAL and who may have additional needs.

Study Skills Programme

This academic year we are proud to be launching a new and

innovative form of support for pupils in Years 5 and 6 and KS3/4 who are

literate in their first language. The Study Skills Programme will be delivered to suitable pupils in

withdrawal by EMTAS Bilingual Assistants. It aims to help

pupils explore how they feel about their learning and their subjects and to

equip them with different tools and strategies they can apply in their lessons

and home learning. For example, pupils will learn to use Google Lens to create

a glossary, have a go at using Immersive Reader to access a text and much more.

The programme is being piloted this half-term with full roll-out planned for

after the October break. To find out more about the programme and your role in

ensuring it impacts classroom practice, sign

up for our free network meeting on Monday 6 November at 9.30.

GTRSB attendance project

Some of our Traveller

students have persistently poor attendance, and this inevitably impacts on

their learning, progress and attainment. This academic year the EMTAS

Traveller Team is going to be working in collaboration with four schools to pilot

an Attendance Project. The aim of the pilot is to support school staff,

Traveller parents and students to collaborate with the aim of improving the

students’ attendance. It will involve regular monitoring of individual Traveller

student’s attendance, regular communication with parents, coffee events and

promotion of the EMTAS Traveller Excellence Award. It is hoped that this will result in a marked

improvement in the attendance of the targeted students, and will also positively

impact their academic progress.

Training offer

We have been overwhelmed by the positive uptake and wonderful feedback from our training sessions over the years. We're keen to maintain this momentum, so why not join us and ensure you feel confident, knowledgeable and equipped with how best to support our learners of EAL? There are several different training opportunities for you to take part in which include our pan-Hampshire network meetings. Our next network meeting takes place on 11th October 3.30-4.30pm with a focus on using ICT to support learners of EAL. Don't worry if you can't make it as we will revisit these sessions throughout the year. View all our training dates via our website.

In addition to our network meetings, we are once again offering SEAL training. This course is the ideal starting point for teachers and TAs, particularly those who are taking on the role of EAL lead within their school. The course consists of 6 full days spread over 2 years, allowing plenty of time to slowly embed best practice within your school. More information about the SEAL course can be found on our website.

We are almost at capacity for our EMTAS Conference which

takes place on 12th October 2023. It's set to be an

incredible event with guest speakers Jonathan Bifield and Sarah Coles along

with Jacob Parvin and Jack Hill. If you'd like to grab one of the last

spaces, please follow this link for

more information.

Finally...

Stay up to date with EMTAS news – sign up for the bulletin.

By the Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisors

This has

been an incredibly busy year for Hampshire EMTAS with 1089 pupils being

referred to us by 30th June. In this blog we delve deeper

into our data and share interesting trends. We reflect on our work with Unaccompanied

Asylum-Seeking Children and share highlights of our support to Gypsy,

Traveller, Roma, Showmen and Boaters. We also celebrate the end of the GCSEs, share

an update to our late arrivals guidance and give details of our brand-new study

skills programme. We reveal the list of schools who have successfully achieved their

EAL Excellence Award and finish with a staffing update. Team Leader Sarah Coles

has the final word in a concluding paragraph.

This academic year in data

Of the 1089 referrals received this academic year across the county, 825 were made by primary schools and 252 by secondary schools. Other referrals were made by special schools and the Virtual School. We have worked with around 303 schools and outside agencies, including some from outside of Hampshire. Rushmoor remains the busiest district for referrals with schools in this area submitting 249 referrals. Basingstoke and Deane followed closely behind, referring 188 pupils.

The top five languages referred to EMTAS this academic year were Ukrainian (149), Malayalam (88), Russian (79), Cantonese (74) and Nepali (72). Not all of the Russian language referrals have Ukraine as the country of origin; they include referrals for pupils from Russia, Latvia and UK born.

There has been a rise in the number of referrals from Albania jumping from 1 in the previous two years to 26 this year. Likewise Turkish referrals over the previous two years number 36 in total but this year there have been 38.

EMTAS has also seen an increase in the number of African languages spoken by children in Hampshire schools with Afrikaans, Akan, Akan Fante, Ghanaian, Herrero, Igbo, Luganda, Lugisu, Malinke, Nigerian, Shona, Swahili, Tigrinya, Twi, Twi Fante and Yoruba all being referred.

EMTAS has

also seen a rise in the number of Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children (UASC) referred

for profiling.

Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children (UASC)

According to the Refugee Council, in the year ending September 2022, the UK received 5,152 applications for asylum from unaccompanied children forced to flee their homes. The children we have met have come from Afghanistan, Albania, Iran, Iraq, Sudan, Turkey and Vietnam. Some of these Unaccompanied Asylum-seeking Children (UASC) have been placed in care and therefore in schools across Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, but we have also been working with the Virtual School to provide profiling assessments for children placed in other counties.

Each pupil has undertaken a long and difficult journey in

search of safety. They then have to learn to deal with a new language, a new

school system and a new culture, without family and friends to support them.

Many are resilient enough to manage this change incredibly well, whilst others

find the new rules and restrictions of school in the UK too challenging,

particularly if they had already left education some time ago in their country

of origin or in some cases have never been to school at all. So, if one of

these brave young people arrives at your school, please do get in contact with

EMTAS as soon as possible so that we can work together to support them as they

learn to adjust to their new life. For more information on UASC, see our Frequently

Asked Questions.

Gypsy, Traveller, Roma, Showmen and Boaters (GTRSB)

As usual the Traveller team have been busy supporting all our schools, families and children. Julie Curtis and Steve Clark, our two Traveller Support Workers (TSWs), have been in schools visiting all our primary aged children whilst Claire Barker, our Traveller Team lead, has been supporting students in secondary schools via our GTRSB clinics. In total, we have supported 285 children this academic year, whilst throughout the year Helen Smith, our Traveller Team Teacher, has helped 22 GTRSB pupils to get places in Hampshire schools.

The school year started off in September with World Funfair Month. We encouraged our schools to celebrate this and provided a pack of ideas and resources to help them get started. Fast forward to June, GRT History Month, and again we provided our schools with a pack of activities and resources to encourage pupils to take part.

We have also launched a couple of new initiatives, including the GTRSB book club. Last term our pupils read The Show Must Go On by Richard O’Neill. One pupil was so inspired by the book that she made an amazing Lego model fairground ride that featured all the characters from the book. We posted a picture on Twitter and Richard O’Neill himself commented. We also launched a gardening club which has been successful in providing some alternative provision for two groups of boys in a primary and a secondary school.

Heritage Language GCSEs

As students come to the end of their time in secondary, it is great to see so many schools celebrating multilingualism by offering Heritage Language GCSEs. This year EMTAS supported more than 152 candidates with 11 different languages, mirroring the amazing diversity of learners in our county. Polish topped the tables with the largest number of candidates, and our Bilingual Assistants have been racing from school to school to carry out all the speaking exams within the assessment window. We are looking forward to results day on 24 August when students can celebrate their achievements and EMTAS staff look on with pride.

Late arrivals

While some students may view GCSEs as the end of an

educational marathon, for others it’s a sprint! Late arrivals (students who arrive

in the UK in Year 10 or Year 11) have very little time to settle into their new

country and new school before they are faced with GCSE exams. Many are new to

English and some must contend with an entirely new alphabet! While not all

undertake a full complement of subjects in this short timescale, it is a

testament to their fortitude and hard work that so many leave with at least one

GCSE. This also reflects the commitment of a host of amazing teachers. Even the

best practitioners sometimes need a little help from their friends, so the team

at EMTAS have recently released updated Guidance

on good practice in relation to Late Arrivals. This aims to help schools

navigate the crucial period when late arrivals first join their school and

ensure they provide the best advice and guidance.

Study Skills Programme

Members of our team have been

busy planning, rewriting and resourcing a brand-new Study Skills Programme for

Bilingual Assistants to offer to schools in the new academic year. The

programme will be suitable for pupils who are literate in their first language

and are working within Band A, B and early stage Band C (particularly for

reading and writing). It will be offered to pupils in Year 5 and 6 as well as

pupils in Secondary school. The aim of the course is to help pupils explore how

they feel about their learning and their subjects and consider different tools

and strategies they can apply in their lessons/homework. It will consist of 5

sessions of 50 minutes to be delivered over half a term. As we write this blog we

are excitedly putting the final touches to the programme and presenting it to EMTAS

colleagues for feedback. We are also looking for schools where our staff could

trial the sessions in the first part of the Autumn term. We thank all our

schools for supporting us while we train our staff to deliver our new programme

after the summer break.

EAL Excellence Award (EXA) celebrations

What a pleasure it is to further celebrate all the schools

who have worked to achieve an EXA award this year. Huge congratulations go

to Sopley Primary, Gosport and Fareham MAT, Portway

Infants, St Matthew's CE Primary, St Patrick’s Primary and St

Bernadette’s Primary who all achieved our Bronze award. Also,

to Roman Way Primary, St Jude's RC Primary, St Michael’s

Juniors, Bordon Infants, Henry Beaufort and Oakmoor for

achieving Silver. Congratulations also go to St Swithun Wells, Cranbourne

Business and Enterprise College, Cove Secondary School and Talavera

Juniors for achieving Gold. We would like to give a special mention to

Merton Infants who are the first school to achieve a revalidation at Gold; an incredible

achievement! We still have a couple of schools to be validated (at time of

print) so please keep up to date by checking our Twitter page

regularly. Well done to all involved and thank you for all your hard

work in supporting your learners with EAL.

EMTAS Staffing update

At the end of the summer term we say goodbye to Lisa Kalim from the Specialist Teacher Advisor team. During her 21-year tenure, Lisa has covered schools in the New Forest, led on Refugees and Asylum Seekers for the team and operated the EMTAS EAL/SEND phoneline, ever-popular with schools. From September, a new system for accessing support for children with both EAL and SEND needs will come into effect so do keep an eye out for information about this change.

We also say good bye to Rekha (Hindi), Kubra (Dari) and to Kasia P (Polish) from the Bilingual Assistant (BA) team. We wish them well in their next ventures.

We welcome Kevin to the BA Team. Kevin joins our Chinese BA

Team and will be working with Cantonese-speaking children from Hong Kong once

he has completed his induction. We welcome Olena and Alex too, both of whom

will be working with children from Ukraine. They will be our very first

Bilingual ELSAs, joining Olha and Vlad, existing members of the EMTAS team.

Together, the four of them will cover referrals for children from Ukraine as

well as providing specialist ELSA support. The new Bilingual ELSA role will begin

in the new term with ELSA training from the Hampshire and Isle of Wight Educational

Psychology (HIEP) team. After their training Olha, Olena, Vlad and Alex will be

deployed to schools. There they’ll work in partnership with school-based ELSAs

to enable Ukrainian children to access ELSA support by removing any barriers

caused by language and/or culture.

Finally, a conclusion by Team Leader Sarah Coles

As you can see, 2022-23 has been no less busy for EMTAS than 2021-22. Stepping into the role of Team Leader has brought with it both challenges and opportunities and whilst I’ve got used to these, the team has continued to work hard around me to make sure our Service continues to deliver professional, high-quality support to children, families and schools. Being at the forefront of developments in the EAL and GTRSB worlds has long been a source of pride to us, and this year we have continued to innovate and to inspire in all sorts of ways, some of which you have read about in this blog. I look forward to continuing in post in September as EMTAS enters its thirty-second year.

By Hampshire EMTAS Bilingual Assistant Eva Molea

In Diary on an EAL Mum, Eva Molea shares the ups and downs of her experience bringing up her daughter, Alice, in the UK. In this instalment, Eva supports Alice with her GCSE option choices.

Here we go again! Alice is finally in Year 9 and, after whizzing through Year 7 and Year 8 with full colours and a School Council Cup for receiving more than 500 achievement points in Year 8 (clever cookie!), our trepidatious wait has finally ended: she will finally choose her GCSE subjects!

As many of you might know already from my previous blogs, in our family we like to investigate, plan, think ahead, be ready… in other words: to stress unnecessarily. Taking GCSE options is throwing open a door on the uncertainty of “what’s next”. Which college? What are the requirements? Which university? Where will our precious daughter move to pursue her career? Just helping you read between the lines, this last question means: where are we relocating to be close to Alice and support her? Ah, the dramas of an Italian mum and dad!

Anyway, invitations to the GCSE guided choices evening had been gratefully received and calendars dutifully marked. Nothing could stop US from being there early and take the necessary time to explore ALL of Alice’s interests.

While Alice was taking taster sessions in school and trying to find out if she really liked what she thought she would like, we (read the royal “We”) started doing the groundwork by searching the Internet for information.

First stop, Alice’s school website. Here we found a whole section solely dedicated to GCSE options with lovely short videos made by the teachers to explain what each course entailed, what the assessment would look like, and which would be the target students for said course. There was also a booklet with all the information, to be perused at one’s own leisure. Very interesting bedtime reading… I found the videos very informative and a great way for me, as a parent coming from a different education system, to discover more about the curriculum and to start forming an idea of which subjects would most suit Alice (or maybe which subject I wished suited Alice...).

The website and the booklet explained clearly which were the core subjects, the extended core, and the other options, and how to combine all these. It also stressed the importance for the students to take their decisions according to their personal interests, skills and future career ambitions rather than being in class with their friends.

Once I found out which were the exam boards for each subject, I quickly examined some past papers to find out what they looked like and to judge which options Alice might enjoy the most. I had no clue.

I then searched BBC Bitesize to see how the GCSE section was organised and discovered that contents had been divided according to exam boards, offering for each of them different topics or perspectives. I thought this would be a good starting point because students could look at the content of other boards as well and gain more information, potentially…

Before the big event, we had virtual parents evening, where in 5-minute slots I was given as much information as possible about my daughter’s achievement and progress. All teachers told me that Alice had an outstanding attitude for learning and that she was always engaged and participative in class and, most importantly, very polite and well behaved. This was a very proud-mummy moment. 😊 Many of them hoped that Alice would take their subject, which meant that she had lots of options (great!), but this didn’t make the process any easier (umpf!).

On the GCSE options evening, I left home with a very nervous Alice. She was worried that we might not have enough time to visit all the subjects that she was interested in (Spanish, History, Dance, Drama, Food Tech, Graphics, Photography, and all the mandatory ones). She was also concerned about the exam requirements for each subject, because she doesn’t enjoy tests one bit… can’t really blame her!

On a chilly and clear spring evening, we got to school before the event started and attended the Deputy Head Teacher’s opening speech. It was a very clear presentation, addressed to the students. It was explained to them that, besides the mandatory GCSEs (English Language, English Literature, Maths, Sciences, and RS*), one subject among History, Geography or MFL was to be picked as extended core. There were two more options to be taken from the extended core and/or all the other subjects offered by the school. Heritage Language GCSEs through the EMTAS service were also encouraged. We were very grateful for this opportunity because it would help Alice keep her home language up to the mark and have her skills recognised.

After the

speech, we set on our discovery journey, going from room to room to find out

about the different subjects. Many teachers had gone through the effort of

creating very captivating and informative displays and were providing detailed

information about the curriculum and the exam, as well as answering the

questions from apprehensive parents (present!) and undecided students.

I soon realised

that we were being submerged by loads of information, but none was helping

Alice to take any decision. All subjects seemed very appealing so I changed

strategy and started asking all teachers just two questions: 1. Why would their

subject be a good choice? and 2. Why, of all the children in their year, should

Alice take it?

Some teachers stressed the academic appeal of their subjects, others praised Alice’s attitude and abilities, but the selling point for her was being very capable and competent in a subject. This was such a confidence booster for her! Another very good selling point for her was the (limited) amount of writing that the subject required.😉

By the end of the evening, we came home with some clearer ideas, but still with a lot of question marks. We decided to leave any decisions to the Easter holidays, as we would have more time to consider and discuss each individual subject. During the school break we sat at a table, with Dad as well, and we discussed pros and cons of each subject. Only five made it to the next round: Spanish, History, Dance, Drama and Food Tech.

For Alice, Spanish was non-negotiable, and this was her extended core subject. She had to pick two more, and would have picked Dance and Drama, which would have helped with her career as “Famous Hollywood Actress” (reach for the stars, girl!), but Dad had different ideas. The pragmatism of the engineer, and the insider knowledge of university selection criteria, made him push for a more academic subject that would unlock other doors, should the long and winding road to Hollywood lose its sparkle.

It took a lot of persuasion, and the promise to pay for a performing arts academy, to get Alice to choose History over Drama. Her decision taken, we filled in the form – which actually included two back-up options, Drama and Food Tech – and hit the “Send” button.

When I questioned Alice about the whole process and whether she had enjoyed it, it came out that she had mixed feelings: she enjoyed the taster sessions in school because they cleared some doubts; she felt the pressure of having to choose and would have welcome more tailored guidance from the school; and she rejoiced when we sent the form because she didn’t have to worry about it anymore and could get back to her normal activities. Everything was in the school’s hands now, and Alice was confident that they would have at heart her best interest when confirming the options.

From my perspective, I was left wondering why schools handle GCSE options in different ways? Surely the expectation was that all children came out of school with the same amount of knowledge and the same mandatory subjects, right? Why did some schools take options in Year 8 and others in Year 9? Once you filled in the form, were your options set in stone?

The only thing

left to do now was sit and wait, which required a lot of patience and poor

Alice had not realised that I would be asking her every day “Have your options

been confirmed yet?”.

PS: We are in a

very lucky position because, despite the education experience in the UK being

new to us, our understanding of the English language is good. But not all

families are in the same position, in particular the ones that have recently

moved to the UK. Here are some ideas that might help make their sailing through

secondary school smoother:

- check whether or not parents require an interpreter to discuss their child's progress at parent evenings

- translate invitation letters using translation tools (eg see Review tab in Word) and follow up by a text message. Consider also using the EMTAS language phonelines

- talk about processes for GCSE options in clear terms. Avoid acronyms and write down important points for families to take home

- ensure your website includes a facility for parents to translate information in their own language. Demonstrate how this works

- have tablets available at options evenings and offer the use of Google Lens for parents to access information on displays

- provide information about Heritage Language GCSEs. Source past papers and add these to the Languages Department's display

- Have KS4 Young Interpreters available to welcome parents at options evenings, give tours and talk about their subjects - not to discuss other pupils' progress

- Use the Immersive Reader and Read Aloud facility on websites such as BBC Bitesize to translate and listen to content relating to GCSE options in parents' languages. Videos hosted on YouTube can also be subtitled in different languages.

*Alice does not enjoy RS, she would rather not go to school when she has that lesson. In advance of the GCSE guided choices, I tried to sweet talk the school to make the subject optional, but I was not persuasive enough.

By Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Kate Grant

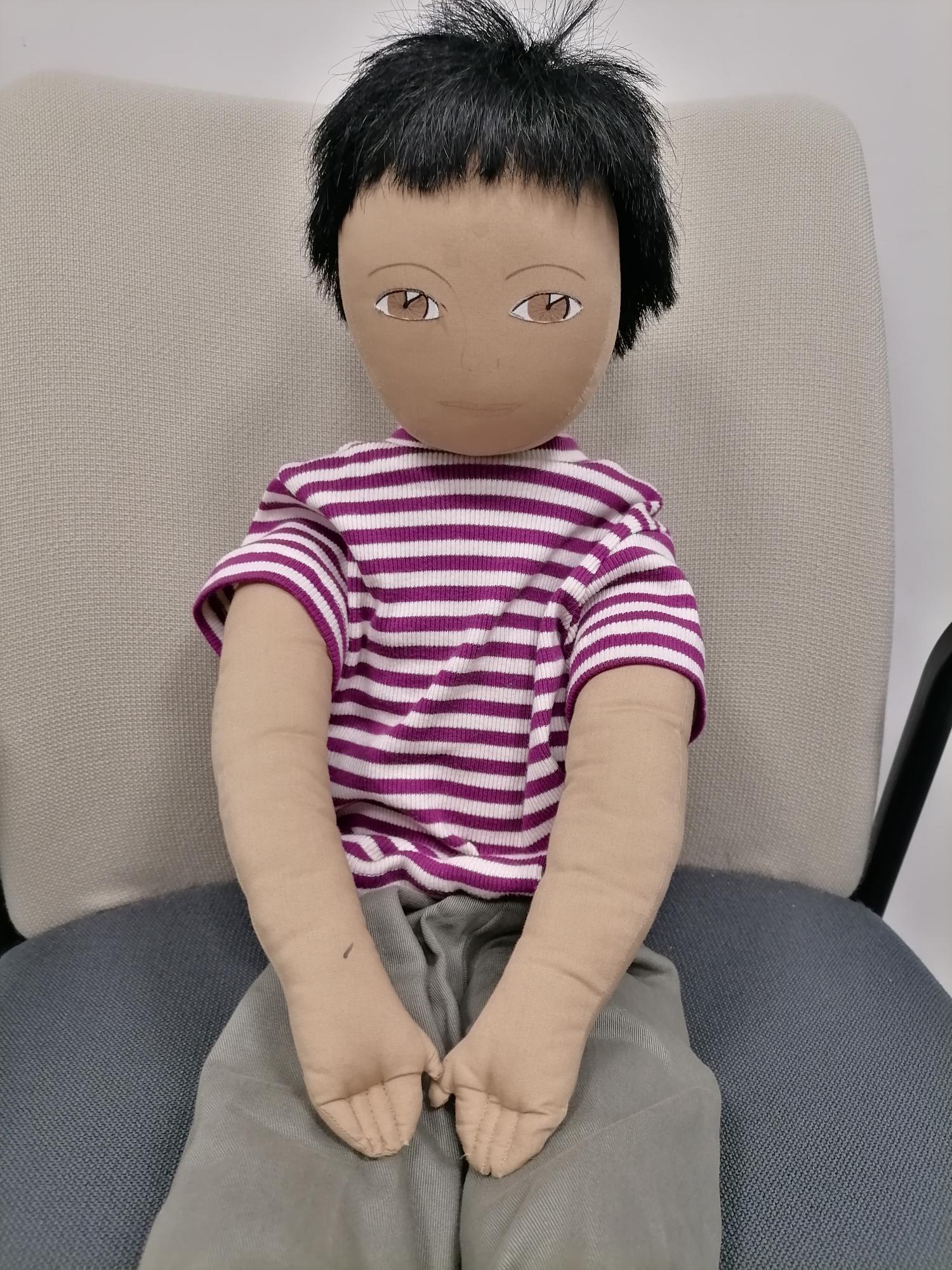

In this blog, Kate Grant interviews Albanian born Persona Doll Avdi. She asks how practitioners can work with EMTAS Persona Dolls to engage young learners with topics such as diversity, culture and stereotypes.

The Persona Dolls approach affords children an engaging, enjoyable and interactive safe space where they can address challenging issues, share their lived experiences and have their voices heard and valued. It helps our youngest learners to develop their emotional literacy and empowers children to use their voice. The approach is designed to facilitate dialogue around bias and stereotypes which so many of our youngest learners will have already encountered.

If you have used EMTAS Persona Dolls previously you will have noticed that they have been taking a well-deserved rest. After all, it’s not easy visiting lots of schools and making friends all over the county - just ask Avdi! Whilst the dolls have been relaxing, Kate has been working behind the scenes on making the use of EMTAS Persona Dolls in school more accessible, relevant and most of all fun. So without further ado please welcome Avdi to tell us more…

Avdi: Përshëndetje (hello) everyone, my name is Avdi and I am from Albania. Kate has asked me to share with you how working with Persona Dolls can help support your youngest learners in school. This is the perfect topic for me to talk about as I have been a Persona Doll my whole life!

Kate: What do you like about being a Persona Doll?

Avdi: One of the main things I love about being a Persona Doll is that I get to travel around the county, meeting lots of children and learning about different schools. I am always amazed by how warmly the children welcome me into their classroom - they sometimes even give me a school uniform to wear. But most of all, I love hearing the brilliant things children say when I go to visit their school and it often surprises their teachers too as we delve into conversations about issues they might not ordinarily get to discuss such as discrimination and inequality. Big topics for our youngest minds.

Kate: How do you support the children?

Avdi: I find that the children see me as being just like

them. This helps create a safe environment where they are happy to share and

talk about aspects of life they may not normally get to discuss. I think of it as providing children with a

window into someone else’s life, but they often find aspects that mirror their

own too. That’s what life is all about, learning

about yourself and others and embracing the similarities as well as the

differences.

Kate: How will teachers find time to use Persona Dolls?

Avdi: We work within the Early Years Foundation Stage and Key Stage 1/2 curriculum, so we are not an add-on. In fact we’re a different approach to teaching Personal, Social, Emotional Development, Knowledge and Understanding of The World and Relationships and Sex Education. Kate has linked all the relevant parts of the curriculum with our guidance documents so that teachers can see the objectives they can cover whilst working with us. For example you will see we provide an authentic way to approach the People, Culture and Communities element of the Early Years Foundation Stage curriculum [1] and the Respectful Relationships aspect of the Key Stage 1/2 curriculum [2].

Kate: What happens when you visit schools?

Avdi: I normally visit once a week for a half term. When I first go into a school, I explain that I am feeling a bit nervous about being somewhere new with people I don’t know yet, and the children discuss how they could help make me feel more comfortable. It’s lovely to hear how kind the children are and accepting of new people - I wish people were always like this. The next week when I return, I am more confident so I let their teacher share a PowerPoint I have made to tell them a bit more about myself, my home, my language and my interests. The children always want to tell me about themselves too and we find similarities and differences with each other.

By week 3 I am really enjoying being with my new group of friends and I share that something has been worrying me. For example, another child has been unkind to me because my hair is different to theirs. The teacher helps me talk to the children and they respond with so much empathy. A lot of the time, the children tell me they have experienced similar things and we talk about what helped them eg speaking to an adult at school. My new friends always give me good advice, so I go away and try some of their ideas. When I return for my final visit, I feel so much better because they supported me. I explain that I must return to my school again and might not see them, but we will still be friends. I like to surprise them with an e-postcard after my final visit. This shows I am still thinking of them and gives me an opportunity to ask them to write to me about our time together.

Kate: What is different about the way EMTAS Persona Dolls work now?

Avdi: Kate is working on making everything available online because we know how busy teachers are and we want everything to be readily accessible in the moment. Once everything is ready to go, it will all be uploaded to our Moodle where you will find the guidance documents, a list of all our Persona Dolls, suggestions for what to do during each visit and some social stories for teachers.

When I visit your school I will have a lanyard with a QR code so that teachers can find what they need instantly. When teachers share the Persona Doll’s PowerPoint it will contain video links to find out more about the culture and language(s) of the doll’s country of origin together with traditional dances and nursery rhymes in first language.

Kate: Is there anything else you want to tell everyone?

Avdi: Just that I am really excited to get back into schools and to meet lots of new friends. Oh, and if any schools would like to pilot our revamped way of working please email Kate at kate.grant@hants.gov.uk.

[1] Explain some similarities and differences between life in this country and life in other countries

[2] The importance of respecting others, even when they are very different from them (for example, physically, in character, personality or backgrounds), or make different choices or have different preferences or beliefs.

By Hampshire EMTAS Team Leader Sarah Coles and Astrid Dinneen, EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor for schools in Basingstoke & Deane

With the increase in numbers of children joining our schools from overseas with very little English, practitioners in schools are asking how best to proceed. Should they first focus on teaching the children English or is there another approach?

EAL best practice tells us that the best thing to do for such children is to include them in the full mainstream curriculum being delivered in schools via the medium of English. This can be scaffolded in various ways. The children should not be withdrawn to be taught English separately or as a prerequisite to being allowed to join their peers in regular lessons. But this immersion approach can seem an alarming response; surely the children will not be able to understand anything and will flounder and fail, people may think. So instead some opt for an ‘English first’ approach. They buy in an online English teaching app or print off worksheets for the children to learn the days of the week and the colours in English whilst their peers are learning about how plants grow or the story of The Titanic or Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

The problem with the English first approach is that far from helping, it actually slows down the children’s progress in their acquisition of English, as well as making it harder for them to feel welcomed and included in the life of their new school. Plus it adds to teachers’ workloads; now they are having to source materials for an entirely separate curriculum as well as plan for the rest of their class.

To illustrate this in more detail, consider these two

approaches for the same newly arrived child whom we shall call Hatice*. Assume Hatice

is new to English (Bell Foundation EAL Assessment Framework Band A, to those in

the know) and literate in Turkish.

Scenario 1: English first

The teacher decides to plan separate provision for Hatice, because they feel their mainstream English lesson is too challenging for Hatice’s level of English. So whilst the other children are preparing to write a letter persuading their Head Teacher to shift the start of the school day back by an hour so they start at 10.00 instead of at 9.00, Hatice will sit on her own and work through some sheets that focus on learning the English words for some colours and common classroom objects. In one example below Hatice is required to draw and colour the correct classroom object in the empty box.

It is a…

|

red |

pen.

|

|

purple |

book.

|

|

|

orange |

chair.

|

|

Fortunately, Hatice is compliant, meaning the teacher can get on with teaching the rest of the class. Hatice spends the whole morning working on these worksheets on her own. She doesn’t disrupt anyone but the teacher notices that she regularly has her head down on the desk and appears to be dozing.

At the end of a couple of weeks at school, Hatice is still very much on the periphery of things in the classroom and needs frequent reminding when she is included in instructions given by the teacher, for example when it’s time to get ready for PE or line up to go to assembly. She spends long periods of time gazing out of the window and generally seems to lack motivation and enthusiasm for anything other than home time.

There has also been a deterioration in her output and she

now very rarely completes the worksheets she is given. Where she has had a go with

tasks that require writing, her handwriting is much less tidy and it seems she is

taking increasingly less care over her work.

With regards to friendships, it seems to be still very early days and Hatice has not formed any strong relationships with her peers. She continues to spend most of her time at break and lunch times on her own.

Her teacher reflects on practice and provision so far. It has

taken a lot of time planning, resourcing and marking the worksheets for Hatice,

yet she does not seem to be making progress. He is not sure what else to do but

feels this is not a sustainable approach in the long term. He is interested in

finding out about alternatives…

Scenario 2: immersion using EAL-friendly strategies

Hatice’s teacher plans to include her in the lesson along with everyone else from the get-go. First off, before the series of lessons begins, the teacher sends Hatice home with a list of words in English to be translated into Turkish with the help of parents. He asks them to talk to Hatice about the concept of ‘persuasion’; what does the word itself mean and in what in real life scenarios might we use persuasion to get the outcome we desire? The teacher recommends the family use a translation tool like Google Translate to help them to do this:

English word/phrase |

Turkish (Türkçe) |

Persuade (someone to do something) |

ikna etmek |

We think |

düşünürüz |

Benefit |

|

Consider |

|

Because |

|

Late/later |

|

Traffic |

|

Drawback |

|

Ensure |

|

Potential |

|

The words the teacher chooses for this are drawn from a model letter which will be used in the lesson the following day. The teacher chooses to write the model himself to incorporate the language of persuasion, different persuasive techniques and ideas already suggested by the children themselves. At other times, he might have used ChatGPT to generate a model in no time.