Site blog

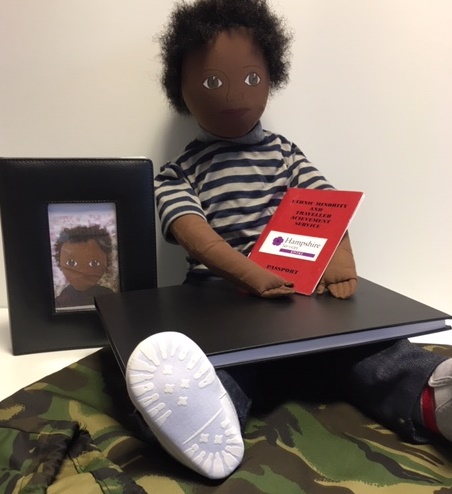

In a previous blog, Hampshire EMTAS colleagues Smita Neupane and Sudhir Lama discussed the use of persona dolls in a project aiming to support transition in Early Years and Key Stage 1 with a particular focus on Service children. In this blog, Cherrywood Community Primary School’s EAL Co-ordinator Dawn Tagima shares one year group’s experience of working with Himal.

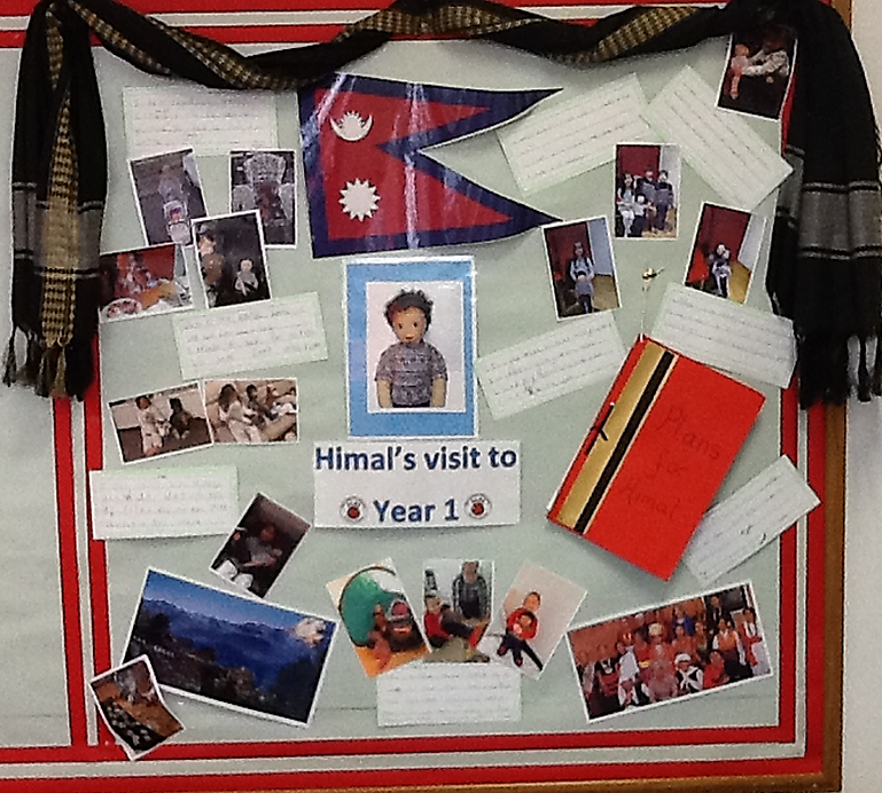

Year 1 children at Cherrywood Community Primary School in Farnborough were delighted to welcome a brand new member to their class, Himal who was from Nepal. Cherrywood Community Primary School has a high number of children with EAL however not many are from a Service background. The school does have experience of working with the local Nepali community and the Year 1 classroom teacher leading this project is herself Nepali. So when the school looked for creative ways to support transition, the persona doll project (and specifically Himal) fitted the bill.

Himal came with his own passport and a 'talking book' which told the children all about his country. The children were told about the fact that Himal was new to this country and how he must be feeling. This encouraged conversations from our children about their own experiences and their own family situations.

Himal was given his own special place to sit in the classroom and the children involved him in every aspect of the school day. They particularly loved sitting and reading to him!

The children made a book about their plans for Himal both in school and at home. Himal was lucky to go home with many of the children to take part in family celebrations and trips out. The children shared this with the class, brought in photos and wrote about it in Himal’s scrapbook.

Himal helped to introduce a brand new topic about feelings and this encouraged the children to produce some amazing work.

Himal has now gone off to another school much to the disappointment of our children but they are always reminded of him with a lovely display in our main hallway and we hope he can come and visit us again when he returns from his 'travels'.

The children gained so much from Himal’s visit. We talked about religious traditions, diversity, beliefs, equality, inclusion, self-esteem, ideas, opinions, sensitivity and pride.

I encourage Early Years and KS1 settings to consider using persona dolls with the children. Simply contact Hampshire EMTAS to discuss the loan of dolls and resources.

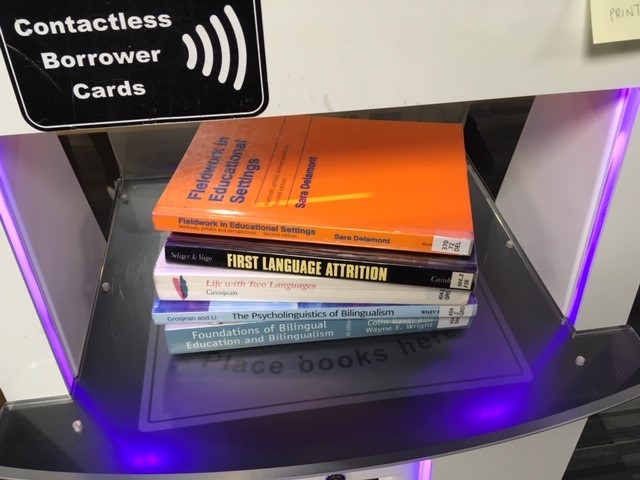

Sarah Coles shares the third instalment of a journal-style account of her reading for the literature review and methodology chapters of her PhD thesis.

Week 5, Autumn 2018

Last time I focused on sequential and simultaneous bilingualism with a light touch on the Critical Period Hypothesis, specifically referencing the age at which one starts learning an additional language, a cause for personal lament. I mentioned how there is a general difference between early starters and late starters, with the acquisition of phonology being the key area in which a difference can be discerned. Apart from that, the notion of there even existing a Critical Period is open to debate, so the jury’s still out. Undaunted I will keep up my efforts, practising asking for things in Turkish when in France.

There are, of course, various factors that are important in second language learning and in this instalment I will talk about two more: aptitude and attitude/motivation. First to aptitude, and the literature reveals that…wait for it…some people are better at learning a second language than others. Ground-breaking stuff you’d never have thought of for yourself, eh? Anyway, in the 50s and 60s, aptitude was a popular area of study and there were many tests developed, each designed to assess language aptitude. These were largely geared towards formal second language learning in the 1960s classrooms of the UK, where students conjugated verbs, did precis and dictation and learned lists of vocabulary (in fact exactly how I was taught French in the 1980s) but rarely – if ever – used the new language to communicate with others. How weird is that? Anyway, when teaching practice evolved to include experience of actual communication (must’ve been after I left secondary school), aptitude testing fell out of favour. There ensued a tumble-weed period of about 30 years until the debate bump-started again in the 1990s when working memory was put forward as a key component of aptitude, conventional intelligence testing having become a subject of much controversy. The net result has been to propose language learning aptitude needs to be redefined to include creative and practical language acquisition abilities as well as memory and analytical skills. Mystic Sarah predicts the conclusion will still be that some people are just better at it than others but that a lot more hot air will have been generated along the way.

Now, if you’re all still keeping up, to attitude and motivation. As you might presume if you give it 5 minutes’ thought, these are difficult things to measure. Gardner and Lambert (1972) helpfully distinguished integrative motivation and instrumental motivation. These go as follows. Integrative motivation is based on an interest in the second language and its culture and refers to the intention to become part of that culture. I wonder if by this they were really talking about assimilation, given they were writing in the 1970s, but that aside they developed tests to measure motivation and attitude. These included factors such as language anxiety, parental encouragement and all the factors underlying Gardner’s definition of motivation. A sort of self-fulfilling prophecy, then. For Gardner, the learner’s attitude is incorporated into their motivation in the sense that a positive attitude increases motivation. This is not always the case, some astute observers note, citing by way of an illustrative example Machiavellian motivation in which a learner may strongly dislike the second language community and only aim to learn the language in order to manipulate and prevail over people in that community. They do like to quibble, these academics.

Instrumental motivation is all about the practical need to

communicate in the second language and is sometimes referred to as a ‘carrot

and stick’ type of motivation. The learner wants to learn the second

language to gain something from it. I can see the carrot here, but where

the stick comes in is less clear, unless it means putting in the effort

required to make progress. Back on planet earth, it is often difficult to

separate the two types. For instance, you might be in a classroom

learning a second language and you might have an integrative motivation towards

your progress in acquiring the second language. You might, for instance,

yearn to have a Spanish boyfriend and fancy going off to live in Madrid or

Barcelona to find him. But you might at the same time have an

instrumental motivation to get high grades in order to ensure you can get onto

the A level Spanish course next year, just in case he turns out to be nothing

more than a pipe dream and you need to rethink your strategic timescales.

People more recently engaged with this aspect of the discussion suggest this

dichotomy (integrative/instrumental) is a bit on the limited side. They

put forward ideas such as social motivation, neurobiological explanations of

motivation, motivation from a process-oriented perspective and task

motivation. So nowadays motivation is seen as more of a dynamic entity,

in a state of constant flux due to a wide range of interrelated factors.

That said, motivation is a good predictor of success in second language

learning. Probably.

By Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Claire Barker

As the summer fast approaches many of us will see our Traveller children and their families disappear for the last weeks of term or dot in and out as they attend the most notable horse fairs around the country. The horse fairs are a valuable and treasured part of the Traveller culture and should be shared and enjoyed in our schools that have Travellers as part of their school community.

The season always opens and closes with Stow Fair which is held in May and October. It takes place at Maugersbury Park and thousands of Travellers come to the showground to trade and parade their horses. This particular fair has been an annual event since 1476 when a Royal Charter was given for a fair to be held.

Locally, in Hampshire, Wickham Fair is always held on 20th May unless that day falls on a Sunday and then the fair will be on 21st May. This year it is an extra special event as this is its 750th anniversary. King Henry III granted a Royal Charter to Wickham in 1269 to hold the fair and markets in the town. It was not a Gypsy Horse Fair at this time but in later centuries it became one of the main English horse fairs for Travellers. A condition of the Charter was that a fair had to be held every year on that day so during World War II a local Traveller placed a carousel in the Square to keep the tradition of the fair going so it could continue after the war.

Appleby Fair is the

big event of the year for Travellers and it happens in the first week in June

and goes on from Thursday to Wednesday with the main events happening on the

Friday, Saturday and Sunday. Like Wickham

and Stow fairs it was also granted a Royal Charter. King James II granted a charter to Appleby in

1685. Many Romany historians claim this

fair is older than five hundred years with some claiming Travellers from the

Roman times travelled to Appleby to trade and parade.

The fairs and the

events surrounding them form a vital heartbeat in the Traveller

communities. It is a time when

Travellers from Ireland, Scotland, Wales and England come together to share

their traditions and values. They trade

together buying and selling horses and goods.

They eat together and socialise and there is lots of catching up with

families from far and wide. The fairs

are often times for family weddings, baptisms and birthday celebrations as the

whole family is together. Many young

Travellers meet their future partners at the fairs.

Romany, Irish Travellers, Scottish Travellers, Welsh Travellers and Showmen come together to ply their goods and catch up on the year’s events. However, the Showmen tend to be at the fairs as service providers running carnivals and catering wagons for all of the Travellers.

Many of the families will take pictures and share them on social media and this provides schools the opportunity to discuss and find out about the fairs and the Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities.

If you have a child from a Traveller community in your school and they are absent for a fair, take the time on their return to ask them to share the magic and experiences they have had. Explore their world together and create a greater understanding of one of Britain’s oldest communities and what they hold dear.

Visit the GRT pages on our website

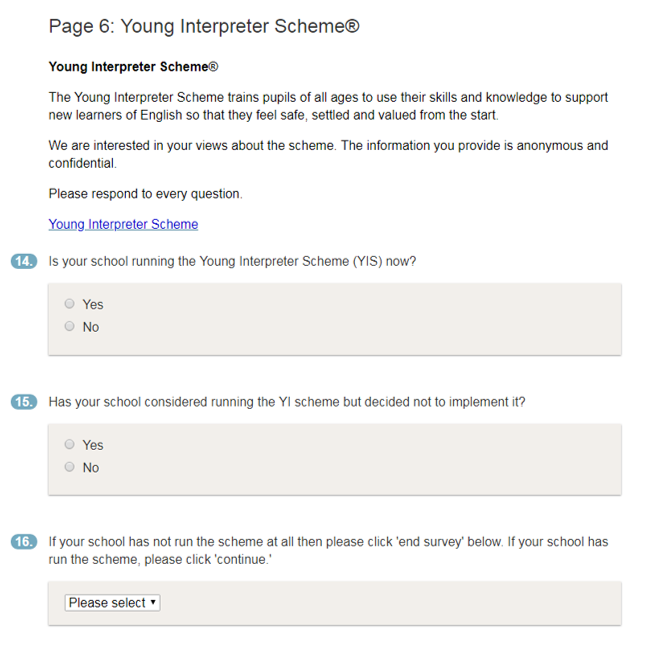

By Debra Page, Masters candidate at the University of Reading

Hi readers. If you’ve not read about me in the Young Interpreters Newsletter, my name is Debra Page. I am conducting research on the Young Interpreter Scheme under the supervision of the Centre for Literacy and Multilingualism at the University of Reading and with Hampshire EMTAS as a collaborative partner. This is the first time the successful scheme will be systematically evaluated since it began 10 years ago. I have worked in research and as an English as a Additional language teacher since graduating with my psychology degree. Now, I am completing my Masters in Language Sciences before starting the PhD. My Masters research dissertation is looking at staff experiences of the Young Interpreter Scheme with a specific focus on motivation for participation in the scheme, views around teaching pupils with EAL and effects of running the scheme on children, staff and schools.

After months of behind the scenes work from the team, a questionnaire has now gone live! The team and I encourage as many staff as possible to complete the questionnaire. This includes people who are running the scheme, who aren’t running the scheme, and staff who work with children with EAL. This anonymous online questionnaire should take around 15 minutes to complete and will allow myself and Hampshire EMTAS to discover what you really think about the scheme, your experiences of participation, and working with children with EAL. Finding out your views in running the scheme (or not) will help EMTAS improve and expand it, plus you will be helping to shape its future.

If you haven’t met me yet, I will be at the Basingstoke Young Interpreters conference on 28th June. If you have any questions about the questionnaire, please email me – debra.page@student.reading.ac.uk.

I hope you choose to help by completing the questionnaire. Please spread the word and share the link!

At a recent EMTAS teachers’ meeting we had an interesting conversation about how often we find ourselves repeating the same messages to practitioners about what good practice looks like for schools working with new arrival learners of EAL. We wondered what methods beyond face to face training and written guidance might be effective at communicating those core principles.

Of course we already have various ways of communicating good practice principles to schools in our local authority and the wider educational community, including via School Electronic Communications, Young Interpreter newsletters, our Twitter account @HampshireEMTAS, online EAL training materials and even posting on national outlets such as the EAL-Bilingual Google group.

In thinking about new ways to communicate our messages, we were inspired by Rochdale Local Authority’s brilliant video ‘Our Story’, which explores the feelings of new arrivals on their first few days at their new school. We decided to produce our own video that focused on how to settle, induct, assess and teach new arrivals to ensure they have the best possible start in the UK education system.

To produce our video, we decided on a software tool called Videoscribe (from Sparkol). For those of you unfamiliar with this technology, Videoscribe produces those videos where a hand draws images on a white canvas to the accompaniment of a narration and possibly a musical score.

The first task was to write a script to cover the key messages:

baseline assessment, with the avoidance of standardised testing

valuing linguistic and cultural diversity

building upon the skills and aptitudes of each child

effective buddying

mainstreaming teaching and learning

Having written a script, we pooled our ideas around choosing a strong metaphor through which we could visualise the main ideas (sports day theme) and any potential images that would need to be drawn. Working with a local artist we then incorporated those drawings with the narration into the Videoscribe software. The resulting video can be viewed below:

Do signpost this to colleagues, and let us know what you think.

Mum, I don’t want to go to school today!

By Hampshire EMTAS Bilingual Assistant Eva Molea

This is the 5th chapter of my Diary of an EAL mum, a series of blogs in which I share the ups and downs of my experience of bringing up my daughter Alice in the UK. So far I have spoken about my experience as an EAL child, how we prepared a cosy nest for Alice to feel at home in her new country, how I tried to support her learning, and the sometimes peculiar choices for lunch. This chapter is about attendance.

Author's own image

Unless I was feeling seriously unwell, for me as a child not going to school was NOT an option. Probably because my parents always told me that going to school was my job and that I had to do it as professionally as possible, which meant being neat and tidy - especially at secondary level, where maintained schools in Italy have no uniforms - and well prepared for my lessons. But mainly because staying at home was DEAD BORING. Not going to school meant being locked up at home, no escape. So why would I ever swap a good 5 hours with my friends for the same amount of time on my own?? Therefore, my approach to the subject had always been simple: we all have to go to school. Until... one morning Alice started crying desperately because she didn't want to go to school and that SHE WANTED TO GO BACK TO ITALY RIGHT THEN.

Oh dear me! She was in such a state that, for the first time, I had to consider not sending her to school. I was very surprised though, as Alice had started going to school everyday at the age of 2 (drop off at 9 am and pick up at 2 pm) and had never told me that she didn't want to go to school. What was I supposed to do? I was worried that, had I allowed her to stay at home that day, she would have asked for it again and again. On the other side, to be fair to the child, we had been in the UK for less than a month and she was still finding going to school very hard and tiring because of the massive effort of processing everything in two languages and because of the linguistic isolation she was still experiencing, which she hated.

So I decided to give her a break and spend the whole day together as a reward for her hard work and intense effort. But I made an agreement with her: this would be the ONE AND ONLY exception in her school life (a bit drastic, I admit, but that's it). In Italy I would have just kept her at home, but here I had to call the school by 9 am to tell them that Alice would not be in school that day and why (schools require all parents to do so, otherwise they call you). I tried and tried but to no avail so I sent an e-mail to the School Office and within minutes I received a reply that it was OK to have Alice at home for that day as homesickness could be a real physical and mental condition. I was very grateful for their understanding. Her school is amazing.

Oh no! I had the hairdresser booked on that day, and a class at the gym I really wanted to go to. AARGH! The wise person that sometimes lives within me told me that instead I needed a plan to make the most of our day together so... We started with the hairdresser (I was not giving this up), next out for lunch, then to the bookshop, played some games at home and cooked a nice dinner for dad who, oblivious of all the things we had done that day, had been only at work (note to self: get a credit card on his bank account).

At the end of Year 1 Alice missed the last day of school too. Our tickets to fly back to Italy for the Summer holidays were a lot cheaper if we flew on the Friday instead of the Saturday, so I went to the School Office and they told me that they understood the issue but the absence was not authorised. I must have had a question mark on my lovely face as the Office, without prompting, explained to me that the Head Teacher had to authorise every absence and holidays were not a good reason to be off school. Obviously I could take my child with me but that would appear as an unauthorised absence on the register. I was very surprised to hear that if Alice made too many unauthorised absences we would have to pay a fine. And being late for school sometimes can count as an unauthorised absence. Aaarghhh! Given my Mediterranean concept of time, I would need to set my watch 10 minutes early to make sure we would be on time!!! The positive news was that Alice would be authorised to be absent during term time for weddings and funerals. So hopefully we will have loads of them. Let’s rephrase this: loads of weddings. Friendly advice: if you wish to know more about attendance policies, please ask the Office at your children’s school or visit the Hampshire EMTAS website.

We navigated swiftly through the rest of Year 1, 2 and 3 with Alice being true to her word up to Year 4 when, all of a sudden after the Christmas break, she started saying that she did not want to go to school. Obviously, I stuck to my principle that she had to go to school every day, until she started to get ill. At the beginning, she was complaining of a constant tummy ache and initially I thought it might have been a bug she had caught in Italy over Christmas. But that went on for a long time and we explored all the possible health conditions, but nothing came out. So, my husband and I started to worry about other issues at school we might not be aware of. So, just to test the waters, I offered her to change school and, much to my surprise, she accepted straight away. She then had to give me reasons for leaving the school she had always been so fond of. And here she opened Pandora's box: friendship issues of two different types, unkind friends and much-too-sticky friends; feeling limited in the choice of children she could play with; feeling the competition on academic grounds; a bit of tiredness because of her busy routines outside school; but the worse thing was the anxiety of not knowing who to talk to for the fear of not being taken seriously. As soon as she had told me all that, she felt immediately relieved, such a big weight having been lifted off her chest. As soon as she told me that, I felt like the worst mother ever. Why hadn't she trusted me enough? Was I being too superficial? Was I too busy to give her the attention she needed? Could have I spotted the sign of her uneasiness by myself? All this called for a large bottle of whisky to drain my sadness into (straight translation of the Italian saying “affogare I dispiaceri nell’alcool”). Sadly, I don't drink...

I addressed the issue with the school the following morning and, at pick up time, Alice and I had a meeting with the teachers who had promptly and delicately discussed this in class with all the children and everything was back to normal. I think I might be repeating myself but her school is amazing.

If I had a lesson to take home from my experience this was to pay attention to everything Alice tells me (which is hard work as she is a chatterbox, I wonder who she takes after...). It is in the little things that we can spot any difficulties our children are facing and an early detection can help us set things right before they become worrying.

Anyway, since then, I have never heard her saying "Mum, I don't want to go to school today". But, they say, never say never…

Sarah Coles shares the second instalment of a journal-style account of her reading for the literature review and methodology chapters of her PhD thesis.

Week 3, Autumn 2018

Week three of the PhD experience and this time I dwell on second language acquisition in early childhood and whether or not there is a difference in one’s eventual proficiency in a language due to acquiring it simultaneously or successively in early childhood. Simultaneous bilingualism is where 2 (or more) languages are learned from birth, ie in a home situation where both languages are more or less equal in terms of input and exposure, a child would develop 2 first languages. I am not volunteering to try and explain this to the DfE, who seem thus far only able to comprehend home situations in which children are exposed to just the one language, but maybe some followers of this blog don’t find it such a strange notion. If so, then perhaps they are in the company of researchers who suggest children growing up in this sort of situation proceed through the same developmental phases as would a monolingual child, and they are able to attain native competence in each of their languages. I personally think there are many variables at play in any teaching and learning situation, things like motivation, confidence, opportunity, resilience and the like, and they all play a part in our lifelong learning journeys. I also think the concept of “native competence” is problematic. What do we mean by that term? How are we measuring it? Do we mean just listening and speaking or reading and writing as well? What about the different registers – does – or should - fluency in the language of the streets count for as much as academic English delivered with Received Pronunciation? Who says so? Then I consider the many monolingual speakers of English I have known; they are not all comparable in their competence in English, despite experiencing a similar sort of education as me, many of them over a similar period of time. Thus ‘native competence’ is not a fixed, immutable thing – in an ideal world, you don’t stop developing your first language skills when you meet the ARE for English at the end of Year 5, do you? ‘No’, I hear you chorus, clearly agreeing with me that it’s a moveable feast. So now even the yardstick implied by the term “native competence” is starting to look a bit flimsy and unfit for purpose. Funnily enough, it wasn’t nearly so problematic until I started all this reading.

Moving swiftly on: if, however, two or more languages are acquired successively, a very different picture emerges from the literature. It has been argued that in successive bilingualism, learners exhibit a much larger range of variation over time with respect to the rate of acquisition as well as in terms of the level of grammatical competence which they ultimately attain. In fact it is doubtful, asserts a guy called Meisel writing in 2009, that second language learners are at all capable of reaching native competence and he says the overwhelming majority of successive bilingual learners certainly does not. Controversial or what? And Meisel is not on his own here; there are many people who agree with the “critical period hypothesis” which essentially boils down to the idea that there is an optimal starting age for learning languages beyond which, and no matter how hard you try, you will never become fully proficient (whatever that means). Johnson and Newport (amongst others) say this age is between 4 and 6 years - which makes me feel a bit downhearted, like I have completely missed the bilingual boat here. Curses.

It all makes for a rather depressing prognosis for older EAL learners, those late arrivals for instance, yet we know from other research that those of our EAL learners who’ve had long enough in school in the UK can achieve outcomes at GCSE that are comparable with their English-only peers, and this can only be a Good Thing, opening doors for them as they go through their teens and into adulthood. For next time, I will try to read something more uplifting, though I expect whatever that turns out to be it will raise more questions than it answers. Keep tabs on the journey as it unfolds using the tags below.

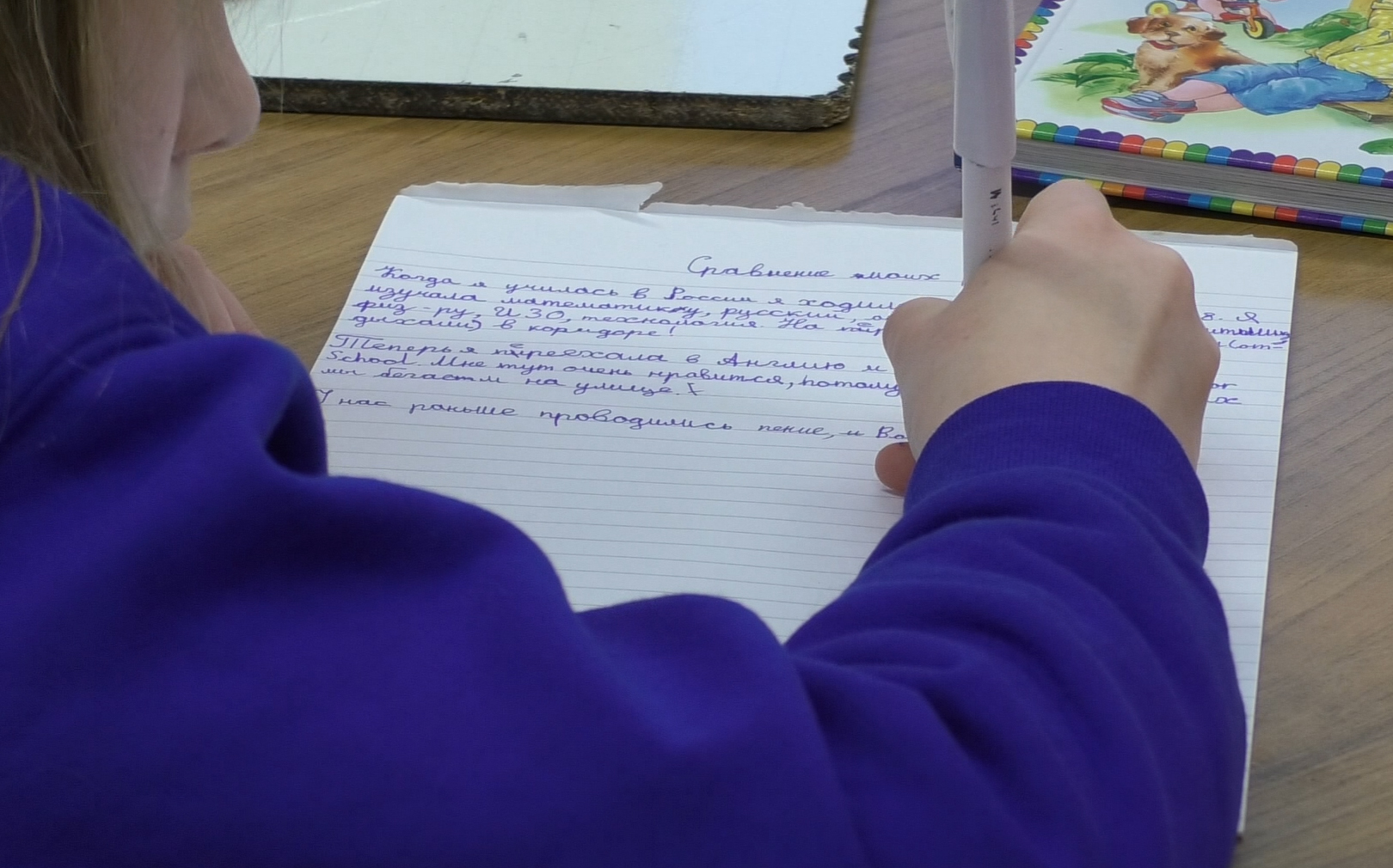

By Hampshire EMTAS Bilingual Assistant Luba Ashton

It can be very challenging for many school practitioners to start working with new EAL arrivals who have either very limited or no English language skills. In this situation, the school staff may have a lot questions and many of them can be about the pupil’s native, or first language skills:

Is the child speaking at an age appropriate level?

How proficient is this pupil in reading and writing?

Is the pupil working above or below age related expectations?

It is very important to find the answers to these basic questions sooner rather than later to start developing the pupil’s English skills with support of their first language prior knowledge and skills.

The best solution is always to invite an EMTAS bilingual assistant to carry out an assessment and get important insight in pupil's educational and cultural background. But when EMTAS are not immediately available, is there anything the school practitioners can do in the meantime, even when they do not share the pupil’s language?

It may sound surprising - but the answer is yes.

This is made possible with the help of the First Language Assessment E Learning resource, created by EMTAS. Using this E Learning tool, practitioners are given advice about how to carry out an assessment of pupil’s skills even in an unfamiliar language.

This resource will explain how to make judgement about reading proficiency; clarify comprehension, notice various features such as accent, intonation, expressing punctuation. It will also help to identify specific strengths and weaknesses in writing; handwriting, quantity, punctuation, self-correction etc.

The E Learning resource provides a practical step by step guide. It is structured into a few parts and gives very detailed instructions on how to assess listening, speaking skills and also reading and writing skills for pupils who are literate in their first language.

Other important steps explained are:

how to prepare for the first language assessment

how to guide and encourage the pupil

best practice to conduct the assessment

how to interpret the outcome of the assessment

how to use the results to further support the development of the pupil’s English skills.

The E Learning resource uses a real life case study of a new arrival Year 6 pupil, Maria. She is a native Russian speaker. The videos provide very useful guidance and enjoyable viewing. It is amazing how much you will be able to say about Maria’s Russian skills without being able to speak Russian!

The materials also provide users with a variety of interactive tools, a check list and links to other resources to support the assessment together with explanations of how to use and where to find them. It is set out to enable the practitioner to make an informed decision as to whether the pupil works at an age appropriate level and help highlight any potential issues.

Feedback from practitioners using this resource has been very positive and I am sure it will be a valuable support for the early assessment of EAL pupils. Visit Moodle for more information.

by Smita Neupane and Sudhir Lama, Nepali Bilingual Assistants with Hampshire Ethnic Minority and Traveller Achievement Service

Have you ever used a Persona doll? Do you know how and why to use a Persona Doll? Persona Dolls are an ELSA resource and emotional literacy support tool used to initiate talk and to share experiences within the classroom. EMTAS were awarded an amount of money in an MOD bid to work with Infant and Early Years settings to introduce Personal Dolls to help all children cope with the demands of moving school, house, and even country with a particular focus on Service children. The Persona Doll project is also designed to involve the family and community and to share experiences with peers. It has an intergenerational element with the involvement of secondary pupils supporting the creation of some of the resources.

In the beginning…

Hampshire is an area rich with Service children across the length and breadth of the county and spanning all the educational phases. The project is designed to support Early Years children but to make it relevant, the experiences of older children was needed and had to be included in the package.

Initially, before the Persona Dolls had joined us, the work started at The Wavell School, with two Nepali Bilingual Assistants from Hampshire Ethnic Minority and Traveller Achievement Service (EMTAS) interviewing students with backgrounds from Fiji, Nepal, Malawi and Jamaica. They shared their stories and were open and honest about their experiences including the difficulties faced during transition and the worries about having a parent in the forces. They spoke of homesickness and missing friends and family, the foods they missed and aspects of their lives that had changed. Some of the students were UK born so had not lived in their parents’ country of origin so they took time to find out as much about their culture and history as they could through their families and community. The students created talking books from this information that included pictures and speech both in English and first language. Some of the books included nursery rhymes from their culture and how to count in their first language. The books are proactive and help bring the Persona Dolls alive. The Wavell children chose the dolls and named them ready for their journey into their schools.

First steps…

When the Talking books were all prepared and each Persona Doll had its name and a passport produced, they were packed up ready to travel with their big note book to record their experiences. The dolls have been taken to infant and primary schools all over the county and the idea is that they stay in that school for roughly half a term and then they are off on their travels again. The doll is taken into the school and introduced into the class where it will be staying and the children get to ask it questions and to find out what it likes and dislikes.

Some ground rules were set:

- doesn’t matter how dirty the doll gets

- no face painting, hands or feet painting of the doll!

- it is not to be used as a reward

- it has to be included on the register

- it has to have its own seat, peg etc.

- it has to have lots of different experiences

- everything has to be recorded in the Persona Doll’s book and shared.

The first doll to leave EMTAS was Himal, a Nepali boy, and he went off to Talavera Infant school and Becky the class teacher. Becky and the class totally embraced this project and the work was amazing. Himal attended an Eid festival where he was gifted new shoes. He went to a Christening. He went to a hot tub party (but just watched). He also shared his feelings about moving to a new school and how this made him feel.

The Persona Dolls generate lots of discussion with the children. It encourages them to think about how they feel when they experience trying something for the first time. It makes them think about what a good friend is and how a good friend can support a new arrival. It allows the children to talk about things that may worry them about transition and about what is happening in their lives at home and at school.

Desired outcomes …

It is hoped that the eight dolls will continue to transition from setting to setting and may even revisit schools they have been to already as can happen with Service children.

One of the aims of the project was to help build up pupil self esteem and confidence. It is hoped that through exposure to the stories children will want to talk and share their own feelings and experiences. Through listening to each other’s experiences it helps children realise that they are not alone in what they are feeling and it is okay to feel that way.

While the project has a fun element of taking the doll to different celebrations and events it is also teaching social and emotional skills through communication and responsibility.

The feedback so far from two schools has been very positive and the children have loved having their guest to stay and were really sad when they left. This too helped teach pupils resilience as many children feel unhappy and lost when their best friend moves on and this helps them build up coping strategies to deal with this and invites discussion within the classroom to look at feelings.

Do you want to be part of this?

If you are a Hampshire school and would like to be part of this ongoing project please email Claire Barker, claire.barker@hants.gov.uk. We would be delighted to have you come on board and training is available this term.

Please see our website for further information on the use of Persona Dolls.

If you are a school outside Hampshire and would like a chat about how to set this up in your area, please contact Claire Barker, claire.barker@hants.gov.uk.

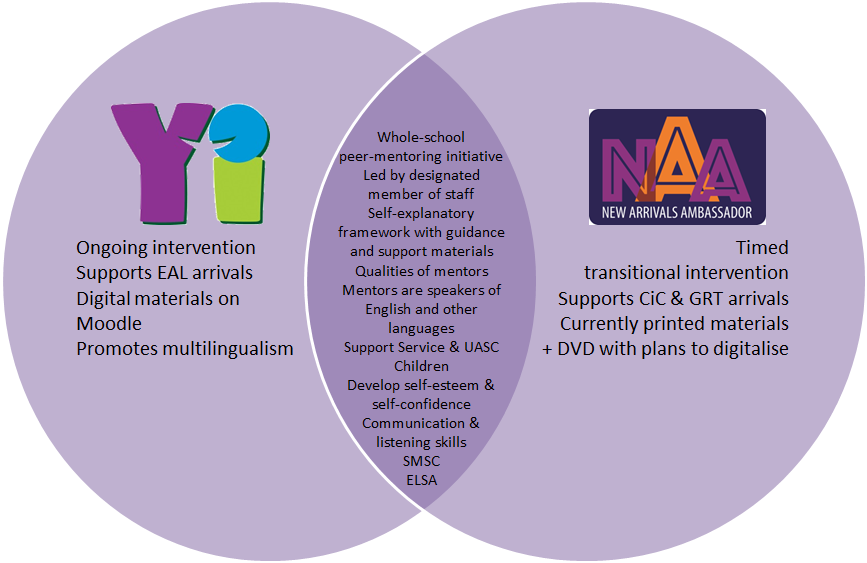

Several articles about the Young Interpreter (YI) Scheme and New Arrivals Ambassador (NAA) Scheme have already featured in the Hampshire EMTAS blog and many schools in Hampshire and across the UK are running either peer mentoring scheme - sometimes both - to support their new arrivals. Other schools have questions. Which scheme should we go for? Do they overlap? What difference is there? Our scheme managers Astrid Dinneen (YI) and Claire Barker (NAA) shed some light.

© Copyright Hampshire EMTAS 2019

Q: How did the schemes come about? Why did EMTAS decide to develop two separate schemes?

Astrid Dinneen: Back in 2004 we saw an increase of new EAL arrivals in schools after the accession of several countries to the EU. To support the well-being of these children, Hampshire EMTAS worked with school-based practitioners in four Hampshire schools to develop the Young Interpreter Scheme. The aim was to create a special role and train children/young people to become buddies and help new-to-English arrivals to feel welcome and settled. We are very proud to have won several awards since piloting the YI Scheme. Can you believe that the scheme is running in over 900 schools now?

Claire Barker: The New Arrivals Ambassador Scheme was borne out of a need by Children in Care, Traveller Children and Service Children to gain extra support when they arrived in schools at irregular times of the school year. Like the Young Interpreter Scheme, the aim was to support the well-being of these groups of children and to ensure they had a smooth transition into their new setting. The idea was to provide a short, sharp, peer mentoring programme lasting about half a term or in line with the needs of the newly arrived child. The scheme evolved after a successful piloting period that involved six schools covering all three phases.

Q: So each scheme is designed to support different groups of children, is it?

Astrid Dinneen: Yes. If your aim is to support EAL pupils whilst promoting the linguistic diversity of your school community then you may like to consider the Young Interpreter Scheme.

Claire Barker: And if your aim is to support all children joining your school at irregular times of the school year, including Children in Care, Traveller children and Service children, then you may like to consider the New Arrivals Ambassadors Scheme.

Astrid Dinneen: Of course some Service children and Children in Care (and particularly Unaccompanied Asylum Seeking Children) will also have English as an Additional Language so it's worth considering your school's needs carefully. Some schools are successfully running both schemes.

Q: How would running both schemes look?

Astrid Dinneen: An important feature of the YI and NAA schemes is that each is delivered by a designated member of school staff. In schools where both schemes are running it’s a good idea for each to be led by different people who can cater for their own scheme’s specificities and also collaborate on joint work. For example, the Young Interpreter Co-ordinator will buddy up Young Interpreters with new EAL arrivals. When a new EAL arrival also happens to be a Service child, then Young Interpreters can work alongside New Arrival Ambassadors to show them the ropes.

Another important aspect of running the Young Interpreter Scheme is that the Co-ordinator regularly meets with the Young Interpreters to guide them and keep them motivated in their role. This follow up phase could be another opportunity for joint work and there are suggested activities on the YI’s Moodle. For example, why not work together to promote both NAA and YI roles by creating a movie trailer?

In terms of pupil selection I think the qualities you would look for in Young Interpreters are similar to those you would expect from a New Arrival Ambassador. Pupils should be friendly, empathetic, welcoming and good communicators. Young Interpreters can be speakers of English only and they can be speakers of other languages too. The same could be said of the NAA, couldn’t it?

Claire Barker: It certainly could and the schemes complement each other when both are running in the same school setting. It is worth remembering that the NAA Scheme is a timed transitional intervention whereas the YI Scheme is ongoing with its support. The aim of the NAA is to develop the self-esteem and self-confidence of the newly arrived child so they are able to function independently after half a term.

I agree with Astrid that the two schemes work better when managed by different people in the school so the lines of what each scheme has to offer do not become blurred. Whilst the skills and qualities of a Young Interpreter and an Ambassador are virtually the same, the job description is very different and each has its own demands and specialist areas for the trained pupils. NAA pupils have to learn to build relationships and trust quickly as their support is delivered over a short period of time. Schools do utilise the trained Ambassadors in different ways throughout the year. Some schools use the Ambassadors to support the new intake in September and to work with classes and tutor groups throughout the academic year. Many schools use the Ambassadors alongside their School Council to represent the school on Open events like Parents’ Evenings. Some schools use their Ambassadors to support existing pupils who are struggling with their well-being and life at school. The scheme has flexibility to be adapted to the setting it is being used in.

Both schemes complement each other and pupils who are Young Interpreters and Ambassadors are highly skilled and proficient peer mentors who can offer linguistic support, well-being support and transition support. Both schemes develop self-esteem and confidence in the Young Interpreters and Ambassadors as well as in the pupils they are supporting and provide opportunities for personal growth.

Q: Where can our readers find out more?

Astrid Dinneen: You can learn more about the Young Interpreters on our website, follow us on Twitter or Facebook or read the December issue of the Young Interpreters Newsletter.

Claire Barker: There is information about the NAA on our website. You can also use the tabs below to read other blogs relating to both schemes.