Site blog

By Hampshire EMTAS Bilingual Assistant Eva Molea

In Diary on an EAL Mum, Eva Molea shares the ups and downs of her experience bringing up her daughter, Alice, in the UK. In this instalment, Eva supports Alice with her GCSE option choices.

Here we go again! Alice is finally in Year 9 and, after whizzing through Year 7 and Year 8 with full colours and a School Council Cup for receiving more than 500 achievement points in Year 8 (clever cookie!), our trepidatious wait has finally ended: she will finally choose her GCSE subjects!

As many of you might know already from my previous blogs, in our family we like to investigate, plan, think ahead, be ready… in other words: to stress unnecessarily. Taking GCSE options is throwing open a door on the uncertainty of “what’s next”. Which college? What are the requirements? Which university? Where will our precious daughter move to pursue her career? Just helping you read between the lines, this last question means: where are we relocating to be close to Alice and support her? Ah, the dramas of an Italian mum and dad!

Anyway, invitations to the GCSE guided choices evening had been gratefully received and calendars dutifully marked. Nothing could stop US from being there early and take the necessary time to explore ALL of Alice’s interests.

While Alice was taking taster sessions in school and trying to find out if she really liked what she thought she would like, we (read the royal “We”) started doing the groundwork by searching the Internet for information.

First stop, Alice’s school website. Here we found a whole section solely dedicated to GCSE options with lovely short videos made by the teachers to explain what each course entailed, what the assessment would look like, and which would be the target students for said course. There was also a booklet with all the information, to be perused at one’s own leisure. Very interesting bedtime reading… I found the videos very informative and a great way for me, as a parent coming from a different education system, to discover more about the curriculum and to start forming an idea of which subjects would most suit Alice (or maybe which subject I wished suited Alice...).

The website and the booklet explained clearly which were the core subjects, the extended core, and the other options, and how to combine all these. It also stressed the importance for the students to take their decisions according to their personal interests, skills and future career ambitions rather than being in class with their friends.

Once I found out which were the exam boards for each subject, I quickly examined some past papers to find out what they looked like and to judge which options Alice might enjoy the most. I had no clue.

I then searched BBC Bitesize to see how the GCSE section was organised and discovered that contents had been divided according to exam boards, offering for each of them different topics or perspectives. I thought this would be a good starting point because students could look at the content of other boards as well and gain more information, potentially…

Before the big event, we had virtual parents evening, where in 5-minute slots I was given as much information as possible about my daughter’s achievement and progress. All teachers told me that Alice had an outstanding attitude for learning and that she was always engaged and participative in class and, most importantly, very polite and well behaved. This was a very proud-mummy moment. 😊 Many of them hoped that Alice would take their subject, which meant that she had lots of options (great!), but this didn’t make the process any easier (umpf!).

On the GCSE options evening, I left home with a very nervous Alice. She was worried that we might not have enough time to visit all the subjects that she was interested in (Spanish, History, Dance, Drama, Food Tech, Graphics, Photography, and all the mandatory ones). She was also concerned about the exam requirements for each subject, because she doesn’t enjoy tests one bit… can’t really blame her!

On a chilly and clear spring evening, we got to school before the event started and attended the Deputy Head Teacher’s opening speech. It was a very clear presentation, addressed to the students. It was explained to them that, besides the mandatory GCSEs (English Language, English Literature, Maths, Sciences, and RS*), one subject among History, Geography or MFL was to be picked as extended core. There were two more options to be taken from the extended core and/or all the other subjects offered by the school. Heritage Language GCSEs through the EMTAS service were also encouraged. We were very grateful for this opportunity because it would help Alice keep her home language up to the mark and have her skills recognised.

After the

speech, we set on our discovery journey, going from room to room to find out

about the different subjects. Many teachers had gone through the effort of

creating very captivating and informative displays and were providing detailed

information about the curriculum and the exam, as well as answering the

questions from apprehensive parents (present!) and undecided students.

I soon realised

that we were being submerged by loads of information, but none was helping

Alice to take any decision. All subjects seemed very appealing so I changed

strategy and started asking all teachers just two questions: 1. Why would their

subject be a good choice? and 2. Why, of all the children in their year, should

Alice take it?

Some teachers stressed the academic appeal of their subjects, others praised Alice’s attitude and abilities, but the selling point for her was being very capable and competent in a subject. This was such a confidence booster for her! Another very good selling point for her was the (limited) amount of writing that the subject required.😉

By the end of the evening, we came home with some clearer ideas, but still with a lot of question marks. We decided to leave any decisions to the Easter holidays, as we would have more time to consider and discuss each individual subject. During the school break we sat at a table, with Dad as well, and we discussed pros and cons of each subject. Only five made it to the next round: Spanish, History, Dance, Drama and Food Tech.

For Alice, Spanish was non-negotiable, and this was her extended core subject. She had to pick two more, and would have picked Dance and Drama, which would have helped with her career as “Famous Hollywood Actress” (reach for the stars, girl!), but Dad had different ideas. The pragmatism of the engineer, and the insider knowledge of university selection criteria, made him push for a more academic subject that would unlock other doors, should the long and winding road to Hollywood lose its sparkle.

It took a lot of persuasion, and the promise to pay for a performing arts academy, to get Alice to choose History over Drama. Her decision taken, we filled in the form – which actually included two back-up options, Drama and Food Tech – and hit the “Send” button.

When I questioned Alice about the whole process and whether she had enjoyed it, it came out that she had mixed feelings: she enjoyed the taster sessions in school because they cleared some doubts; she felt the pressure of having to choose and would have welcome more tailored guidance from the school; and she rejoiced when we sent the form because she didn’t have to worry about it anymore and could get back to her normal activities. Everything was in the school’s hands now, and Alice was confident that they would have at heart her best interest when confirming the options.

From my perspective, I was left wondering why schools handle GCSE options in different ways? Surely the expectation was that all children came out of school with the same amount of knowledge and the same mandatory subjects, right? Why did some schools take options in Year 8 and others in Year 9? Once you filled in the form, were your options set in stone?

The only thing

left to do now was sit and wait, which required a lot of patience and poor

Alice had not realised that I would be asking her every day “Have your options

been confirmed yet?”.

PS: We are in a

very lucky position because, despite the education experience in the UK being

new to us, our understanding of the English language is good. But not all

families are in the same position, in particular the ones that have recently

moved to the UK. Here are some ideas that might help make their sailing through

secondary school smoother:

- check whether or not parents require an interpreter to discuss their child's progress at parent evenings

- translate invitation letters using translation tools (eg see Review tab in Word) and follow up by a text message. Consider also using the EMTAS language phonelines

- talk about processes for GCSE options in clear terms. Avoid acronyms and write down important points for families to take home

- ensure your website includes a facility for parents to translate information in their own language. Demonstrate how this works

- have tablets available at options evenings and offer the use of Google Lens for parents to access information on displays

- provide information about Heritage Language GCSEs. Source past papers and add these to the Languages Department's display

- Have KS4 Young Interpreters available to welcome parents at options evenings, give tours and talk about their subjects - not to discuss other pupils' progress

- Use the Immersive Reader and Read Aloud facility on websites such as BBC Bitesize to translate and listen to content relating to GCSE options in parents' languages. Videos hosted on YouTube can also be subtitled in different languages.

*Alice does not enjoy RS, she would rather not go to school when she has that lesson. In advance of the GCSE guided choices, I tried to sweet talk the school to make the subject optional, but I was not persuasive enough.

Comments

By Hampshire EMTAS Team Leader Sarah Coles and Astrid Dinneen, EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor for schools in Basingstoke & Deane

With the increase in numbers of children joining our schools from overseas with very little English, practitioners in schools are asking how best to proceed. Should they first focus on teaching the children English or is there another approach?

EAL best practice tells us that the best thing to do for such children is to include them in the full mainstream curriculum being delivered in schools via the medium of English. This can be scaffolded in various ways. The children should not be withdrawn to be taught English separately or as a prerequisite to being allowed to join their peers in regular lessons. But this immersion approach can seem an alarming response; surely the children will not be able to understand anything and will flounder and fail, people may think. So instead some opt for an ‘English first’ approach. They buy in an online English teaching app or print off worksheets for the children to learn the days of the week and the colours in English whilst their peers are learning about how plants grow or the story of The Titanic or Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

The problem with the English first approach is that far from helping, it actually slows down the children’s progress in their acquisition of English, as well as making it harder for them to feel welcomed and included in the life of their new school. Plus it adds to teachers’ workloads; now they are having to source materials for an entirely separate curriculum as well as plan for the rest of their class.

To illustrate this in more detail, consider these two

approaches for the same newly arrived child whom we shall call Hatice*. Assume Hatice

is new to English (Bell Foundation EAL Assessment Framework Band A, to those in

the know) and literate in Turkish.

Scenario 1: English first

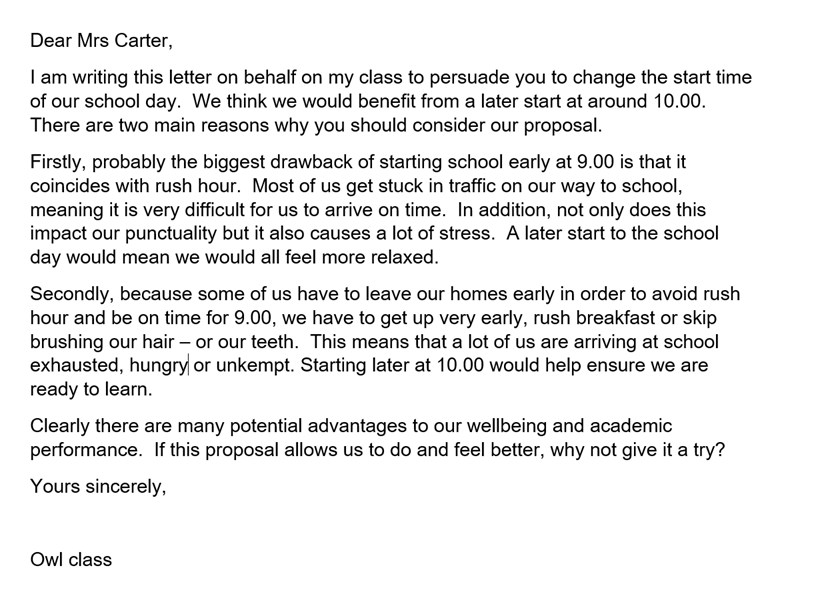

The teacher decides to plan separate provision for Hatice, because they feel their mainstream English lesson is too challenging for Hatice’s level of English. So whilst the other children are preparing to write a letter persuading their Head Teacher to shift the start of the school day back by an hour so they start at 10.00 instead of at 9.00, Hatice will sit on her own and work through some sheets that focus on learning the English words for some colours and common classroom objects. In one example below Hatice is required to draw and colour the correct classroom object in the empty box.

It is a…

|

red |

pen.

|

|

purple |

book.

|

|

|

orange |

chair.

|

|

Fortunately, Hatice is compliant, meaning the teacher can get on with teaching the rest of the class. Hatice spends the whole morning working on these worksheets on her own. She doesn’t disrupt anyone but the teacher notices that she regularly has her head down on the desk and appears to be dozing.

At the end of a couple of weeks at school, Hatice is still very much on the periphery of things in the classroom and needs frequent reminding when she is included in instructions given by the teacher, for example when it’s time to get ready for PE or line up to go to assembly. She spends long periods of time gazing out of the window and generally seems to lack motivation and enthusiasm for anything other than home time.

There has also been a deterioration in her output and she

now very rarely completes the worksheets she is given. Where she has had a go with

tasks that require writing, her handwriting is much less tidy and it seems she is

taking increasingly less care over her work.

With regards to friendships, it seems to be still very early days and Hatice has not formed any strong relationships with her peers. She continues to spend most of her time at break and lunch times on her own.

Her teacher reflects on practice and provision so far. It has

taken a lot of time planning, resourcing and marking the worksheets for Hatice,

yet she does not seem to be making progress. He is not sure what else to do but

feels this is not a sustainable approach in the long term. He is interested in

finding out about alternatives…

Scenario 2: immersion using EAL-friendly strategies

Hatice’s teacher plans to include her in the lesson along with everyone else from the get-go. First off, before the series of lessons begins, the teacher sends Hatice home with a list of words in English to be translated into Turkish with the help of parents. He asks them to talk to Hatice about the concept of ‘persuasion’; what does the word itself mean and in what in real life scenarios might we use persuasion to get the outcome we desire? The teacher recommends the family use a translation tool like Google Translate to help them to do this:

English word/phrase |

Turkish (Türkçe) |

Persuade (someone to do something) |

ikna etmek |

We think |

düşünürüz |

Benefit |

|

Consider |

|

Because |

|

Late/later |

|

Traffic |

|

Drawback |

|

Ensure |

|

Potential |

|

The words the teacher chooses for this are drawn from a model letter which will be used in the lesson the following day. The teacher chooses to write the model himself to incorporate the language of persuasion, different persuasive techniques and ideas already suggested by the children themselves. At other times, he might have used ChatGPT to generate a model in no time.

Having diligently completed her pre-learning at home with

the help of her parents and discussed the concept of persuasion in Turkish, Hatice

is very proud to bring in a dual-language glossary she has started in her

special book. She places it on her desk

next to her pencil case. Her new buddies seem to be taking an interest in the

stickers she has stuck on her book and this adds to her feeling of pride.

She is also pleased to recognise the vocabulary she has researched and translated in a handout placed on her desk by her teacher. Everybody else is given the same handout. Hatice is intrigued and delighted to see she might not be doing different work today. Plus a Teaching Assistant approaches her holding a tablet and shows her how to scan the text to translate it into Turkish. Hatice smiles and chuckles as she reads the translation and discovers the text is a letter asking their head teacher to delay the start of the school day.

Highlighters are distributed and her buddies start a conversation. They’re highlighting parts of the letter. Hatice checks the tablet to see the translation again and tries to match the highlighted text to the translation. She starts to neatly annotate her letter in Turkish. Her teacher looks happy so she continues her annotations and adds to her dual-language glossary words such as ‘firstly’, probably’, ‘clearly’ etc. Her buddies highlighted them so Hatice thinks they must be important.

Later on, the children are to write their own letter using

features of the original. Hatice’s teacher suggests to her that she could write

her letter in Turkish. Hatice happily engages with this, writing fluently and

at length, sometimes self-correcting and adding punctuation. She writes in

paragraphs and her sentence starters seem to vary. She even attempts to

incorporate some English vocabulary eg ‘firstly’ and ‘clearly’. This reassures Hatice’s

teacher who can see she has lots of ideas and things to say. He notices Hatice

sometimes looks at her peers’ writing - both are quite happy to show her their

work – and is making use of the tablet to communicate with them using translation

apps.

What now?

Experimenting with EAL pedagogy has proved promising as it’s meant Hatice has felt included, motivated and able to meet curriculum objectives in a differentiated way. Her teacher would like to build on this by trying other EAL strategies such as substitution tables and Dictogloss, planning further opportunities for listening and speaking and continuing the use of Turkish as a tool for learning. To explore these further why not join one of our online network meetings?

EMTAS

training courses | Hampshire County Council (hants.gov.uk)

*This child's name is pronounced /hætidʒe/

Comments

By the Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisors

Welcome to this new academic year. In this blog you will find out what’s in store for 2022-23, starting with a staffing update and news of fantastic heritage language GCSE results. We also share ideas and resources to celebrate World Fun Fair Month and details of upcoming training opportunities. Finally, we have news of our continued support for refugee arrivals and celebrate the achievement of schools on their EAL Excellence Award.

Staffing

To kick off, we have some news about our staffing. We are delighted to welcome new Bilingual Assistants this year, Olha Herel (Ukrainian), Jenny Lau (Cantonese) and Kubra Behrooz (Dari).

From our Teacher Team, last term we bade farewell to Specialist Teacher Advisor Jamie Earnshaw, who worked with schools in Eastleigh, Fareham and Gosport. In his place, Lynne Chinnery is now covering Fareham and Gosport districts in addition to Havant & Waterlooville and the Isle of Wight. As a temporary measure whilst we wait for our new recruit to join the EMTAS Teacher team, Claire Barker is back on the team and covering Eastleigh and East Hants whilst Kate Grant has added Hart to her brief. Helen Smith is covering Rushmoor and all things GTRSB – that’s Gypsy, Traveller, Roma, Showmen and Boater in case you are wondering about the new nomenclature there, following the lead of the Traveller Movement and ‘The Pledge’.

Finally, Michelle Nye, the erstwhile Team Leader, left EMTAS at the start of this term to take up the role of Executive Head of the Virtual School for Hampshire and the Isle of Wight. In her place, Sarah Coles is currently acting Head of Service with Claire Barker as her trusty sidekick, acting up into the Deputy Team Leader role.

GCSE results

2021-22 was a bumper year for Heritage Language GCSEs. In the summer 2022 exam series, EMTAS Bilingual Assistants supported 106 students in schools across the county with their Heritage Language exams. Students took GCSEs in 11 different languages, with Persian added to the list thanks to Sayed Kazimi, our Pashto, Dari and Farsi-speaking Bilingual Assistant who supported our first ever Persian candidate. Our Admin team gathered in the results from schools as soon as we started back in September; the full list is now on the EMTAS website, but we are thrilled to be able to report that 60 of those students achieved Grade 9, with another 25 being awarded Grade 8. Our congratulations go to all those students.

World Fun Fair Month

September is dedicated to celebrating our Showmen children and families. World Fun Fair Month was started by Future 4 Fairgrounds which is a community organisation set up by 6 Showmen women to celebrate the Showmen community as well as raise awareness of the challenges they face. Our team is proud to have supported WFFM by collating ideas and resources for schools to use throughout September to celebrate this important month for our Showmen families. There is still time to share children’s work with us so we can display it on the EMTAS website and Moodle. You can share anything from your school’s celebrations by sending it via email to EMTAS@hants.gov.uk with ‘World Fun Fair Month 2022’ in the subject line, ensuring it includes no photos or names of children (only the names of the schools the children attend will be published).

For your diaries - upcoming training opportunities

Back by popular demand this term are our online network meetings which will be co-delivered after school by different members of the EMTAS Teacher Team. There are three dates for a session focussing on catering for the needs of refugee arrivals: September 22nd, October 11th and November 8th. We also have three dates for a session focussing on the needs of new to English arrivals on September 27th, October 20th and November 16th. There are details of how to join these meetings on our website.

This half-term we also recruit for our Supporting English as an Additional Language (SEAL) course. This course is suitable for teachers, EAL co-ordinators and support staff in both primary and secondary phases. This is a two-year course: it comprises of six units taught over 6 days. It is held in Winchester and starts in November 2022 and ends in May 2024 therefore it can be budgeted over three academic years. The benefits of sending a member of staff on this course are far-reaching. Not only does it upskill a member of your staff in becoming an expert in English as an Additional Language (EAL) but it also leads to raising EAL standards at your school. Through the course colleagues will explore different cultural practices, learn how to confidently assess pupils with EAL including whether a child’s needs are SEN or EAL, discover the latest technologies to help support pupils with EAL and become more aware of how to support parents of children with EAL. The course also helps towards gaining the EAL Excellence Award. For more information about SEAL, please visit our website.

Plans are already underway for our not to be missed EMTAS conference which will take place in the Autumn of 2023. Keep an eye out for save the date information which will be sent out this Spring term. We look forward to seeing many of our blog readers at this event which promises to be as thought-provoking as ever.

Refugee arrivals

EMTAS referrals for refugee pupils are continuing to arrive and we are pleased to see many school colleagues book on our network meetings to find out more about how to cater for this group of children and young people. We are also delighted to see schools make good use of our resources centre by borrowing dual language stories, translated texts and devices such as talking pens.

Some schools in Hampshire and on the Isle of Wight have been

receiving requests from Ukrainian parents for patterns of attendance/provision

that differ from full time attendance at school/participation in mainstream

lessons every day. In many cases families are looking to return to Ukraine once

it is safe to do so and it is therefore understandable that they may want their

child(ren) not to miss out on the Ukrainian curriculum. In a recent School

Communication also available on our Moodle we share some considerations and

points to bear in mind which may help with the decision-making around such

requests as well as alternatives to explore.

Later this term we look forward to adding a new blog to our refugee series where we will unpick the differences and similarities between refugees arriving from Afghanistan and those arriving from Ukraine. Later this academic year we will also be sharing cultural information about these countries on our website.

EXA news

In our previous blog we celebrated the achievement of schools on their GRT and EAL Excellence Awards. As we begin this new academic year, we congratulate even more schools on achieving their EAL Award. A huge well done to Endeavour Primary, Shakespeare Infants, Chalk Ridge Primary and St Matthew's CE Primary School for all their hard work and dedication in improving their practice and provision for their learners with EAL.

Those of you who are currently on your journey to achieve an EXA award may have noticed some changes to the criteria we use to validate. We hope this will further improve standards and that you find it more user friendly. Any schools currently in the process are invited to submit their evidence using either the old, new or a mixture of criteria. As always, if you have any questions regarding the EXA award, please don’t hesitate to get in contact with your Specialist Teacher Advisor.

Heritage Honours Award

Would you like to encourage your learners from BME, EAL and GTRSB backgrounds and reward them for their hard work and perseverance? The Heritage Honours Award was created to celebrate the achievements of these learners and is open to all Hampshire and Isle of Wight schools. Learning a new culture and/or English as an additional language can be a long and difficult path so why not recognise this by nominating them for a Heritage Honours Award? Relevant areas of success could include exceptional progress in acquiring EAL, overcoming adversity, first language achievements eg use of first language as a tool for learning, active involvement in the EMTAS first language pupil training program, storytelling, writing in L1, Heritage Language GCSEs, etc. and promoting linguistic, religious and cultural awareness in school. For more information and details of how to nominate please go to the Heritage Honours section on our Moodle.

Finally...

We are all looking forward to continuing working with you and to sharing more blogs written by different members of our fabulous team. Come back next week to read Lynne Chinnery's Memoirs of a Travelling Teacher.

Comments

By the Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisors

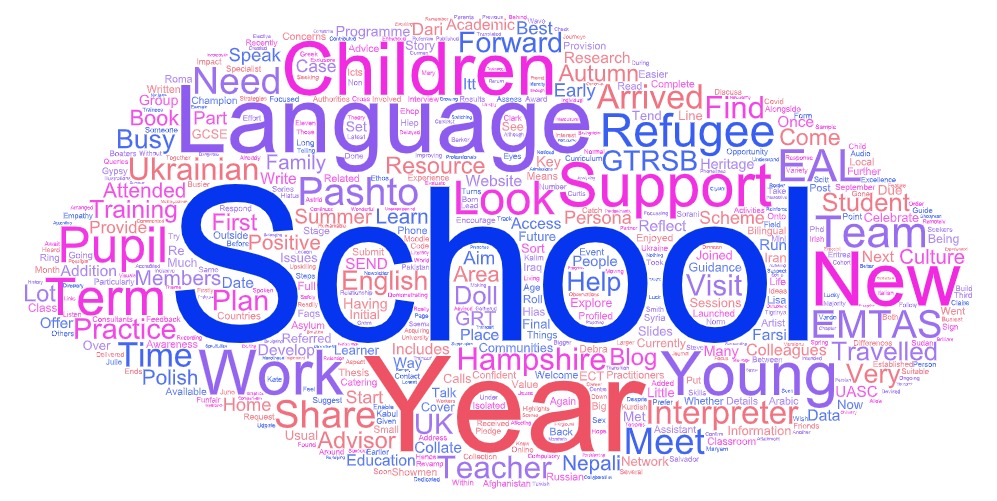

1077 pupils, 60 languages, 70 countries of origin; 2021-22 has been a year like no other. In this blog, we reflect on the highlights of a very busy academic year and share some of the things schools can look forward to after the summer. Notably we discuss our response to our refugee arrivals and Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children, review our SEND work, examine how our research projects are progressing, feedback on our GTRSB work, give an update of developments around the Young Interpreter Scheme, ECT programme and Persona Dolls and celebrate the end of support for Heritage Language GCSEs for this academic year. EMTAS Team Leader Michelle Nye concludes this blog with congratulations, farewells and an update around staffing.

Response to refugee arrivals

As we post this blog, 275 refugee arrivals have been referred to Hampshire EMTAS in 2021-22. These pupils predominantly arrived from Afghanistan and Ukraine with a small number coming from other countries such as El Salvador, Pakistan and Syria. EMTAS welcomed new Bilingual Assistant colleagues to support pupils speaking Ukrainian, Dari/Farsi and Pashto and a lot of work went into supporting and upskilling practitioners in catering for the needs of new refugee arrivals. We delivered a series of online network meetings where colleagues from across Hampshire joined members of the EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor team to find out more about suitable provision. We launched a new area on Moodle to share supporting guidance and resources. We published two blogs – Welcoming refugee children and their families and From Kabul to a school in Basingstoke – Maryam’s story. And we added two new language phonelines to our offer, covering Russian and Pashto/Dari/Farsi.

In the Autumn term you can look forward to further dates for network meetings focussing on how to meet the needs of refugee new arrivals. There will also be sessions where we will explore practice and provision in relation to catering for the needs of pupils who are in the early stages of acquiring English as an Additional Language (EAL). In addition to this, we are planning a blog in which we will interview our new Ukrainian-speaking Bilingual Assistant to share with you the specificities of working with Ukrainian children. The team is also working alongside colleagues from HIAS and HIEP to collate FAQs from queries and observations related to asylum seekers and refugees who have recently arrived into Hampshire.

Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children (UASC)

It’s been a busier than usual year for UASC new arrivals too, with 11 young people being referred to us having made long and dangerous journeys to the UK on their own. They have travelled from countries such as Sudan, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan and Eritrea and speak a variety of languages including Arabic, Kurdish Sorani, Tigrinya and Pashto. The majority have been placed in schools outside of Hampshire and so have been profiled remotely, but some are now attending Hampshire schools meaning that we have been able to visit them in person. There is lots of advice available for schools receiving UASC onto their school roll on our website. This includes detailed good practice guidance and Welcome to Hampshire (an information guide written for the young people) translated into several key languages with audio versions also available.

SEND work

The SEND phone line run by Lisa Kalim continues to be well used by schools as their initial point of contact with EMTAS when they have concerns about a pupil with EAL and suspect that they may have additional needs. There have been almost 100 calls made on this line to date this academic year. After school tends to be the busiest time so if you can ring earlier, it may be easier to get through first time. It is helpful to have first read the information on our website about steps to take when concerned that a pupil with EAL may also have SEND and to have gathered the information suggested in the sample form for recording concerns before calling. In many cases advice can be given over the phone without the need for a teacher advisor visit to the school. However, for others a visit by one of our Teacher Advisors can be arranged. This year, our Teacher Advisors have been especially busy with this aspect of our work and have completed over 60 visits since September. These have focused on establishing whether individual pupils may have additional needs as well as EAL or not and also on the enhanced profiling of those for whom a school will be submitting a request for assessment for an EHCP.

Ongoing research

It’s been a catch-up sort of year for Sarah Coles, with a delayed start to her data collection due to Covid affecting the normal transition programmes schools have for children due to start in Year R in September. Through the Autumn, Spring and Summer terms, Sarah has made visits to schools to work with the eleven children who are involved in her research. The children are either Polish or Nepali heritage and they were all born in the UK. This means they have not experienced a monolingual start to life, hence Sarah’s interest in them and their language development.

The children have talked about their experiences of living in two languages – although as it turns out they’ve had very little to say about this. Code-switching is very much the norm for them and having skills in two languages at such a young age seems to be nothing remarkable or noteworthy in their eyes. They’ve also done story-telling activities in their home languages and in English, once in the autumn term and again in the summer. This will enable comparisons to be made in terms of their language development as they’ve gone through their first year of full time compulsory schooling in the UK.

Early findings suggest big differences between the two language groups. The Nepali children tend to prefer to respond in English and most have not been confident to use Nepali despite all demonstrating that they understand this language when it’s used to address them. This has been the case whether they are more isolated – the only child who has access to Nepali in their class - or part of a larger group of children in the same class who share Nepali as a home language. In contrast, the Polish children have all been much more confident to speak Polish, responding in that language when it’s used to address them as readily as they use English when spoken to in that language. This has been the case whether they’re more isolated at school or part of a bigger cohort of children.

The field work ends in the summer with final interviews with the children’s parents and teachers. Sarah then has a year to write up her findings, submit her thesis and plan how best to share what she’s learned with colleagues in schools.

Young Interpreter news

This academic year Astrid Dinneen launched the Young Interpreter Champion initiative. Young Interpreter Champions are EAL consultants outside Hampshire who are accredited by Hampshire EMTAS to support schools in their area in running the Young Interpreter Scheme according to its intended ethos. Currently 6 Local Authorities are in our directory with more colleagues enquiring about joining.

Established Young Interpreter Champions met on Teams in the Summer term to find out how the Young Interpreter Scheme is developing in participating Local Authorities and to plan forward for 2022-23. They also heard more about Debra Page’s research on the Young Interpreter Scheme under the supervision of the Centre for Literacy and Multilingualism at the University of Reading and with Hampshire EMTAS as a collaborative partner.

The aim of Debra’s research is to evaluate the scheme’s impact on children’s language use, empathy and cultural awareness by comparing Young Interpreter children and non-interpreter children. Her third and final wave of data collection took place during the Autumn term 2021. This year is dedicated to analysing her data and writing her PhD thesis. Her chapter on empathy and the Young Interpreter Scheme is complete and she will soon write a summary about this in a future Young Interpreters Newsletter. She also looks forward to sharing results of what is found out in terms of intercultural awareness and language use.

GRT update

It has been a very busy year for the GRT team. Firstly, we will be moving towards using the more inclusive term of Gypsy, Travellers, Roma, Showmen and Boaters – GTRSB when referring to our communities.

As usual our two Traveller Support Workers Julie Curtis and Steve Clark have been out and about supporting GTRSB pupils in schools. The feedback they receive from schools and families is very positive. The pupils look forward to their opportunity to talk about how things are going and they value having someone listen to them and help sort out any issues. Our Traveller team lead Helen Smith has been meeting with families, pupils and schools to discuss many issues including attendance, transport, exclusions, elective home education (EHE), relationships and sex education, admissions and attainment.

Helen has been lucky enough to work with some members from Futures4Fairground who have advised us on best practice when including Showmen in our Cultural Awareness Training. Members of the F4F team also attended and contributed to our schools’ network meeting and to our GTRSB practitioners’ cross-border meeting.

The team was busy in June encouraging schools to celebrate GRT History Month. We devised activities and collated resources around the theme of ‘homes and belonging’. Helen attended an event to celebrate GRTHM at The University of Sussex. It was aimed at all professionals involved in working with members from all GTRSB communities in educational settings. It was encouraging to see so many professionals attending. Helen particularly enjoyed watching a performance of Crystal’s Vardo by Friends, Family and Travellers.

Sarah and Helen have been making plans for celebrating World Funfair Month in September. We have already put some ideas together for schools on our website and hope to develop them further with help from our friends at Future4Funfairs.

Looking forward to next year, as well as reviewing our GRT Excellence Award, we will be looking at how best to encourage and support our schools to take the GTRSB pledge for schools - improving access, retention and outcomes in education for Gypsies, Travellers, Roma, Showmen and Boaters. Schools that complete our Excellence Award should then be in a position to sign the pledge and confirm their commitment to improving the education for all their GTRSB families.

Early Career Teachers (ECT) programme

The Initial Teacher/Early Career Teacher programme that Lynne Chinnery is preparing for next academic year is really coming together. After a large proportion of student teachers stated they were still uncertain how to support their EAL learners after completing their training programmes (Foley et al, 2018), the EMTAS team decided to do something about it.

Lynne has collated a set of slides to train student and early career teachers on best practice for EAL learners by breaking down the theory and looking at practical ways to implement it in the classroom. The sessions cover such areas as supporting learners who are new to English; strategies to help students access the curriculum; assessing and tracking the progress of EAL learners; and information on the latest resources/ICTs and where to find them.

The programme has been made as interactive as possible in order to reinforce learning, with training that practices what it preaches. For example, it provides opportunities for group discussions that build on the trainees' previous experiences. The trainees can then try out the strategies they have learnt once they are back in the classroom.

Lynne Chinnery has already used the slides on a SCITT training programme and the feedback from that was both positive and useful. One part the students particularly enjoyed and commented on was being taught a mini lesson in another language so that they were literally placed in the position of a new-to-English learner. This term, Lynne and Sarah Coles have met with an artist who is designing the graphics for the training slides - once again demonstrating a feature of EAL good practice: the importance of visuals to convey a message. The focus in the autumn term will be a reflective journal for student teachers to use alongside the training sessions.

Heritage Language GCSEs

This has been a particularly busy year for us supporting students with the Heritage Language GCSEs. We received 136 requests from 32 schools. We provided support for Arabic, Cantonese, German, Greek, Italian, Mandarin, Polish, Portuguese, Russian and Turkish. For the first time this year, we also supported a student with the Persian GCSE.

The details of the packages of support we will be offering next year will be shared with you in the Autumn term. You can also check our website. Remember to get your referrals in to us in good time!

We wish all students good luck as they await their results! A big thank you to Jamie Earnshaw for leading on this huge area of work. Sadly Jamie is leaving at the end of the Summer term. Claire Barker returns from retirement to take over the co-ordination of Heritage Language GCSEs from September.

Persona doll revamp

Persona Dolls are a brilliant resource which provide a wonderful opportunity to encourage some of our youngest learners to explore similarities and differences between people and communities. They allow children time to explore their own culture and learn about the culture of someone else. The EMTAS team currently have around 20 Persona Dolls, all of which come with their own identity, books and resources from their culture to share and celebrate.

Now some of you may have noticed that our Persona Dolls have been enjoying a little hiatus recently. What you will not have seen is all the work that is currently going on behind the scenes in our effort to revamp them. Within our plans we aim to provide better training for schools so that you as practitioners feel more confident in using them within your classrooms. Kate Grant is also looking at ways to incorporate technology so that you can have easier access to supporting guidance, links to learn more about the doll’s heritage and space to share the experience your school has of working with our Persona Dolls. EMTAS know that our schools recognise the value of this wonderful resource and look forward to seeing the positive impact they will have on their return.

Finally, a conclusion by Team Leader Michelle Nye

The last time EMTAS topped 1000 referrals was 7 years ago so it has been one of the busiest years we have experienced in quite a while. This was due to the exceptional number of refugee referrals and to a spike in Malayalam referrals whose families have come to work in our hospitals. On top of this we had over 120 new arrival referrals from Hong Kong; these children are here as part of the British Hong Kong Nationals Overseas Programme.

EMTAS recruited additional bilingual staff and welcome Sayed Kazimi (Pashto/Dari/Farsi), Tsheten Lama-North (Nepali), Kubra Behrooz (Dari), Tommy Thomas (Malayalam), Jenny Lau (Cantonese) and Olha Herhel (Ukrainian) to the team.

We are delighted that schools have been committed to improving their EAL and GRT practice and provision and have achieved an EMTAS EAL or GRT Excellence Award this year. Congratulations to St Swithun Wells, Bramley CE Primary, St James Primary, Marchwood Infant, New Milton Infant, St John the Baptist (Winchester District), Bentley Primary, St Peters Catholic Primary, Swanmore College, Poulner Junior, Grayshott CofE Primary, The Herne Primary, Wellington Community Primary, Marlborough Infants, John Hanson, Fleet Infants, Fairfields Primary, Swanmore CofE Primary, Brookfield Community School, Fernhill School, New Milton Junior Elvetham Heath and Red Barn Primary.

We say goodbye to Jamie Earnshaw, Specialist Teacher Advisor, who has been with EMTAS since 2012. During his ten-year tenure, his work has included producing the late arrival guidance on our website, developing our Accessing the curriculum through first language: student training programme now available for pupils in both primary and secondary phases, and for leading on our Heritage Language GCSE work. His are big shoes to fill and we will miss him immensely; we wish him every success in his new venture.

Enjoy your summer holiday and see you again in September.

Data correct as of 30.06.2022

Word cloud generated on WordArt.com

Comments

By Hampshire EMTAS Bilingual Assistant Eva Molea

In Diary of an EAL Mum, Eva Molea shares the ups and downs of her experience bringing up her daughter, Alice, in the UK. In this instalment, Eva tries to understand ability grouping in secondary school settings.

Imagine it was July,

and you were sitting in the garden on a sunny afternoon, with your cup of tea

and a lovely book, engrossed in your reading. Everything was great, and you were

looking forward to an idle couple of hours until you had to taxi your child to

their afterschool club. Hold on to this dream as long as you can…

My dream couple of hours vanished as I straightened up on my chair and tried to make sense of what Alice was telling me. It seemed that, from Year 8 onwards, the school would be grouping children according to their abilities, and that some subjects would be bundled together. Therefore, if a child happened to be brilliant in one subject, but not so shiny in the other one, they would be put in the group (= set) of the less shiny subject.

My first reaction was: This is crazy! One of us must have not understood correctly. Check again.

My second reaction was: This is unfair and penalising – with all the self-confidence and self-esteem consequences, especially after the pandemic – whereas the children should be praised for their abilities and efforts.

I tried to think of the information in the school prospectus, of all the things that my friends with older children at the same school had told me, looked at the school policies but could not find an answer, so I decided to write to the school.

I blamed poor Alice because “she certainly had misunderstood what she had been told and it would not be fair to penalise her in Spanish because of her results in Maths”. Spanish and Maths sounded like a strange matching.

Anyway, less than 2 hours later I received a phone call from the Head of Maths (!) who had kindly made time to talk to me about my email. He explained that for the first time, the following academic year, the school would be trying a different type of subject association which saw Maths with MFL, and English with Science. He also explained that to be in the highest set, Alice would have needed high marks at the last tests. Before calling me, he had discussed Alice’s attainment with the Head of MFL, who had confirmed her being an able linguist, which is often the case with bilingual children. Even so, she might have gone down a set because of her attainment in Maths. My understanding was that there were also some timetabling issues involved.

I was very confused. Like many EAL parents, I had been educated in a different system, where children are taught in mixed abilities groups from Year 1 to Year 13, classes are up to 30 children, every child has favourite subjects or is confident in some areas more than in others, and children learn from each other, and from each other’s mistakes as well. Therefore, I was not prepared for this kind of grouping, and wished I had known before, as it would have given us the chance to put in place some support for Alice so that she could feel more confident with her Maths.

I did ask why parents, especially the EAL ones, were not informed about the grouping system and it seemed that nobody had ever raised the issue. So far. The lovely gentlemen said that he would discuss with the SLT how to communicate more clearly with parents.

Needless to say, I was none the wiser after this conversation, because even if I could in part understand the school’s reasons, I still felt that the children were not being treated fairly.

A lot of questions sprang to my mind: would Alice be able to move from one set to the other if her attainment improved? And would she be able to move from one set to another during the academic year or would she need to wait to be in Year 9 to be in the higher set? Would moving up in Maths automatically mean that she would move up in Spanish too? And what if she moved down? And what if she wasn’t appropriately challenged in a lower set?

At this point, my curiosity had been ignited, so I did a little research about different types of grouping in secondary school.

I looked at the EMTAS Position Statement on the placement of EAL learners, which clearly explains that the language barrier might not allow students to demonstrate their full knowledge or abilities and, funnily enough, Maths is the only subject in which Alice still thinks in Italian.

The position statement highlights that EAL learners might understands ideas or concepts in first language, including those which are more abstract and complex, and be confidently able to demonstrate this understanding in their first language. However, when asked to demonstrate this understanding in English, they might lack the necessary language of instruction to fully understand the task they are being asked to complete. Equally, they might not have a sufficient command of English vocabulary or language structures to be able to convey their understanding to school staff or peers.

According to the Position Statement, a thorough EAL assessment would be needed to find out the knowledge and ability of a child in first language and it would be good to discuss any decisions about grouping/setting/streaming with the learner and their parents/carers, who might not be familiar with the UK education system and how decisions on grouping are taken.

I did further research on setting and streaming and the outcome will be part of an new piece of work EMTAS is doing on EAL Parents FAQ.

Fortunately, a few days after my conversation with the Head of Maths, I received an email saying that Alice had done really well in her last Maths test and, therefore, she would be placed in the highest sets in both subjects. I was very pleased for her. She was safe for this year but would have to work very hard in Maths to remain in the highest set. Obviously, I set Dad on a mission to find the best maths revision guides and exercise books, so that Alice could have a little extra practice every now and then, and kindly asked him to patiently instil his love for Maths in our daughter (after all he is an engineer, offspring of a Maths teacher). Patiently being the key word here, I can see a Maths tutor coming our way. ?

Comments

By EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Lynne Chinnery

With an average of one in six pupils in UK schools learning English as an Additional Language (EAL), every student teacher will unquestionably need a solid understanding of EAL pedagogy and how to apply it in the classroom. But how important is EAL these days? You may have noticed a distinct lack of focus on EAL in the OFSTED Inspection Framework but there is at least a mention in the DfE’s Teachers’ Standards. Does this mean that an understanding of EAL good practice is no longer as important for practitioners as it used to be? Is EAL support and training no longer required apart from a cursory nod?

Clearly not, as the number of EAL learners in our schools is increasing, not declining. The Bell Foundation states that, “nearly half of all teachers in England will be teaching pupils from diverse backgrounds, and superdiversity in schools is becoming the norm.” This is no surprise to the Hampshire EMTAS team as our number of EAL referrals and requests for support continues to grow.

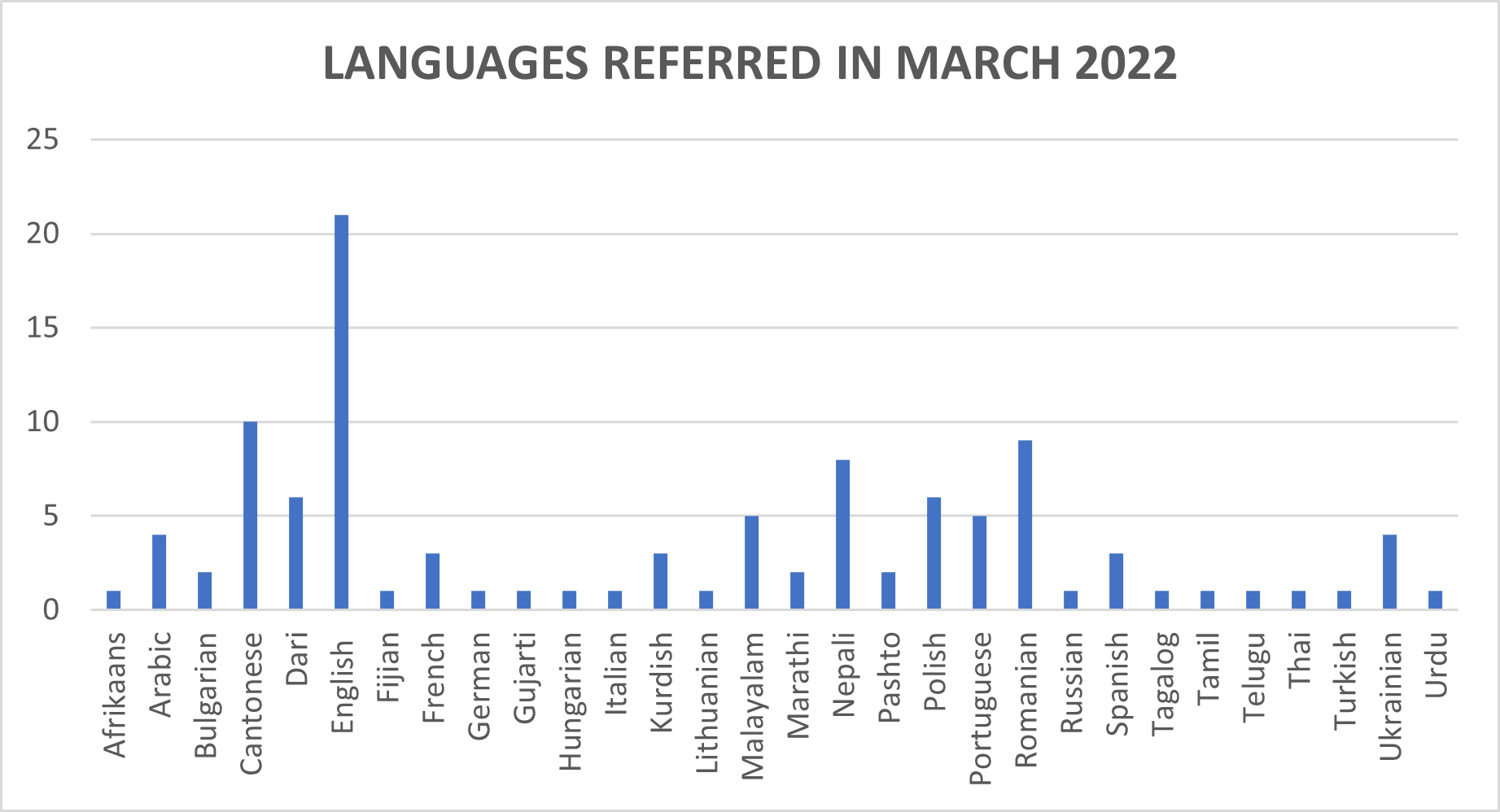

In fact, schools sought our support for a total of 30 different languages in March alone! It is therefore rather worrying that EAL is a key area flagged up by both student teachers and newly-qualified teachers as one they feel the least prepared in.

In a study by The Bell Foundation and the University of Edinburgh (Foley et al, 2018), a third of student teachers reported that they had “little” or “little to no” understanding of how to support the language and literacy needs of their EAL learners. And although the majority of trainees understood that teachers had a responsibility for EAL, approximately one half of them said that they had received no EAL input at all during their school placements. It was even found that the teacher trainers themselves lacked confidence in their own knowledge and experience of EAL. This is despite the fact that standard five in the Teachers’ Standards states that teachers must “have a clear understanding of the needs of all pupils … including those with EAL” and “be able to use and evaluate distinctive teaching approaches to engage and support them.”

Furthermore, the National Curriculum Statutory Guidance (2014, Section 4.5) clearly states that teachers must ‘take account of the needs of pupils whose first language is not English’, showing that EAL should be an important component of teacher education programmes. EAL is not a separate subject, but rather a pedagogy that should be considered throughout the curriculum, and needs to be taught as a distinct discipline to ensure its theory, practice and strategies are understood. Students’ training courses can differ greatly from region to region and the opportunities for EAL experience will depend very much on the schools they are placed in and the training provided on their course, all of which seem to be rather hit and miss.

Some areas that were lacking in Initial Teacher Training

(ITT) programmes were identified in the Bell Foundation/Edinburgh University study and

they include:

- understanding the value and use of home

languages in the classroom

- the need for student teachers to expand their

own knowledge about other languages and their differences

- developing understanding of the cognitive and

emotional demands of moving between languages

- learning to apply their EAL theory and

practice across all subjects and levels.

I was particularly surprised that understanding the value of other languages in the classroom was identified as one of the missing areas. It seems to me that promoting the first language is one of the key elements of good EAL practice and the responsibility of every school. Without it, we are ignoring a significant part of an EAL learner’s life and identity, as well as missing out on a valuable resource right there in the classroom. (If you would like ideas and resources to support the use of the first language across the curriculum, see the section Use of First and Other Languages on our Moodle.)

Whatever EAL training is put in place for ITTs, it will need to continue and be built upon as teachers enter their first years of teaching and beyond. The NQT programme was replaced with the Early Careers Framework (ECF) in September 2021 and this phase extended to two years. The Early Career Teachers (ECTs) will have support from a dedicated mentor as well as time off timetable for induction activities and training, in the hope that fewer of them will leave the profession during their induction period. The DfE are also hoping that the ECF will build on the ITT and “become the cornerstone of a successful career in teaching”.

Yet once again, we have a discrepancy between what is expected and what is taught. The new ECF is closely aligned to the Teachers’ Standards, and yet makes no reference to EAL, which means that as long as the training providers stick to the ECT programme, the inclusion of EAL is discretionary. And so it would seem that the EAL training provided in the ECF could be as ad hoc as that in the ITT.

The last annual DfE survey of NQTs (which was pre-Covid) showed that many were concerned about their ability to teach EAL. I doubt much has changed since then. In her article How well prepared to teach EAL learners do teachers feel? Emily Starbuck says that “NQTs have consistently given this aspect of their training the lowest rating.” In fact, most of those questioned reported having had little or no training on their ITT to enable them to meet the needs of EAL learners. They also felt that it would be difficult to improve their practice due to a lack of external guidance; many stating that CPD opportunities and school support in the field of EAL were unavailable. As one teacher in the survey said, “Most of the training was geared towards mainstream.”

The Bell Foundation report clearly states that in order for all teachers to be prepared to meet the needs of EAL learners, Initial Teacher Education should not be seen as a separate component in a teacher’s career but should be viewed as the first step in their continuing professional development. It is therefore important that the groundwork on EAL taught to trainee teachers in the ITT stage is built upon as they progress through their careers.

Why then is EAL not being addressed more in Initial Teacher Training (ITT) programmes and the ECF? Without knowledge of best-practice principles in the field of EAL and guidance on how to apply them, student teachers and early career teachers are more likely to make poor or uninformed decisions when faced with learners who are new to English as well as more advanced EAL learners. Some examples the EMTAS team have seen include the deceleration of students, unnecessary withdrawal from the classroom and the use of inappropriate resources. Inexperienced students and teachers are also more likely to judge a student’s ability from their spoken communication (BICS), and therefore fail to provide enough support with their academic and literacy skills (CALP). (To understand BICS and CALP, watch this: Terms to Know: BICS and CALP.)

Newly-qualified and student teachers will need ideas and strategies that they can use to scaffold the curriculum content for their EAL learners; an hour-long session on ‘the basics’ of EAL is not going to suffice. With this in mind, I have been working with my colleagues at Hampshire EMTAS on an in-depth ITE and ECF training programme to fill this potential void and deliver up-to-date training. Using the pedagogy of EAL to guide the trainees, but with practical ideas for EAL support in the classroom, we hope that our training programme will give the attendees the confidence they need.

We hope that the termly training sessions will run as a steady progression from Initial Teacher Training right through to the end of the Early Career Teacher programme. The training will consist of a set of modules, based on the findings of The Bell Foundation's recent research, but using strategies, resources and ideas from across the Hampshire EMTAS Teacher Team. Each session is designed to be as interactive as possible, with plenty of group activities and discussion, so that the trainees have the opportunity to share their experiences in the classroom and learn from each other. This will have the additional benefit of promoting the value of collaborative work by having the trainees experience it for themselves.

There will be a reflective journal to

accompany the course so that the ITTs and ECTs can review their learning and

thoughts from each session, as well as plan strategies to explore once back in

the classroom. Some of the areas that will be included in the training are:

- understanding the

stages of language development such as the silent period

- ways to include

the EAL learner in the classroom and scaffold their learning

- collaborative work

and setting/grouping

- knowing how to

advise parents on bilingualism/multilingualism

- assessment,

tracking and planning for EAL.

We also ensure that student teachers and ECTs are made aware of appropriate, up-to-date resources and where to find them.

By equipping students and teachers with the knowledge and strategies they need, I hope that they will view EAL in a similar way to Sheila Hopkins: 'multilingualism should be seen as a valuable resource and an integral part of a child’s identity, rather than as a hindrance'.

I will continue to work and build on the training course

and hope to share my progress once I'm done – although as we all know from Kolb’s

Learning Cycle, a teacher’s work, just like a student’s, is never really

“done.”

References

Naldic (2016) EAL Learners in Schools

The Bell Foundation (2018) University of Edinburgh Research Report, English as an Additional Language and Initial Teacher Education

Department for Education (2021) Teachers’ Standards in England

The

Bell Foundation (2019) University of Edinburgh Executive Summary, English as an

Additional Language and Initial Teacher Education

The

Bell Foundation (2020) Designing New ITE Curricula: EAL Content

Recommendations

DfE (2019) Early Career Framework

DfE

(2018) Newly Qualified Teachers: Annual Survey, 2018 Research Report

Hamish

Chalmers (2018) How well prepared to teach EAL learners do teachers feel?

Sheila Hopkins (2022) Supporting trainee teachers to teach EAL pupils

Hampshire EMTAS Guidance Library

Comments

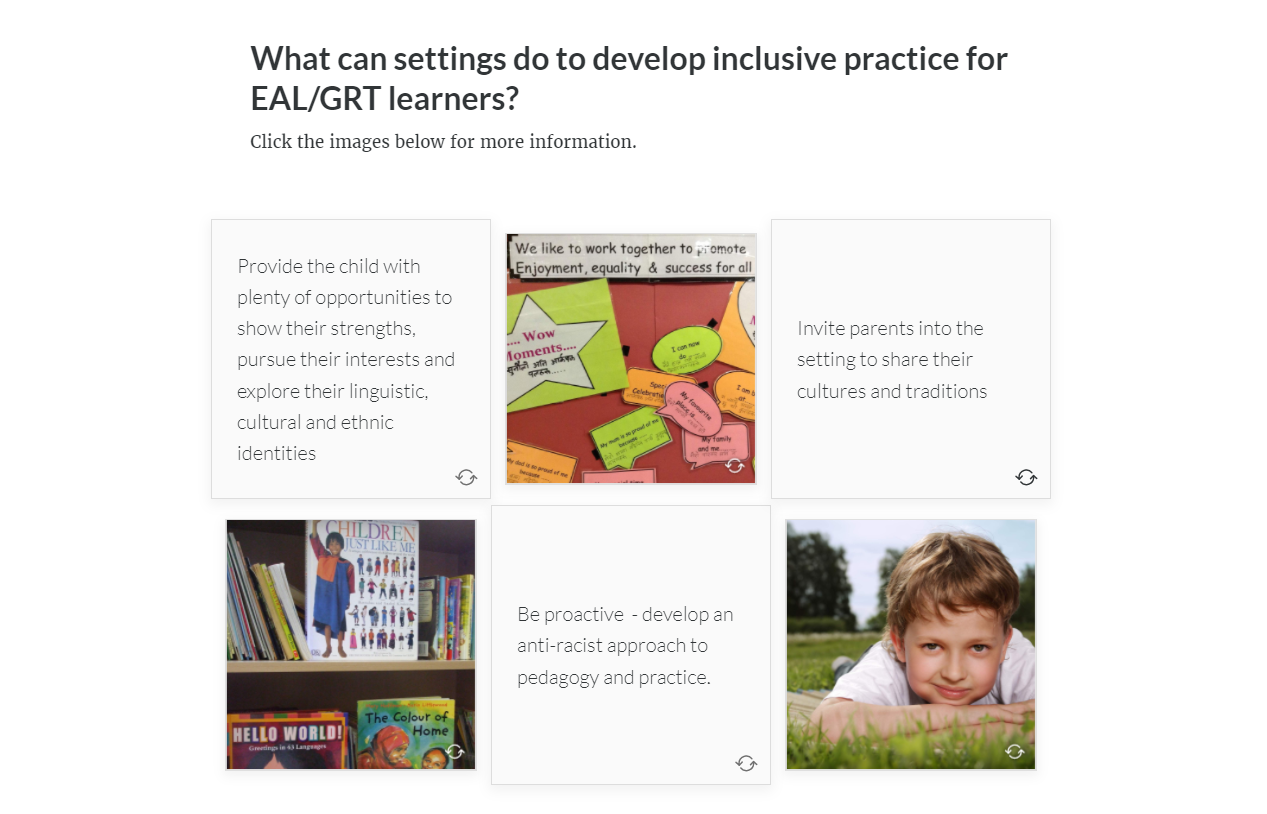

Written by Helen Smith, Lynne Chinnery and Sarah Coles, all of the Hampshire EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor team, this blog presents the latest addition to the suite of EMTAS e-learning modules, 'Developing Culturally Inclusive Practice in Early Years Settings'. The new module is aimed at practitioners working in Early Years settings with children and families for whom English is an Additional Language (EAL), or who are from Gypsy, Roma & Traveller (GRT) or Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) backgrounds.

The EYFS Statutory Framework states that “providers have a responsibility to ensure positive attitudes to diversity and difference. Not only so that every child is included and not disadvantaged, but also so that they learn from the earliest age to value diversity in others and grow up making a positive contribution to society”. The themes of inclusion and diversity pinpointed in this statement form the foundation on which the EMTAS Early Years e-learning module sits.

Why Early Years e-learning?

Practitioners in Early Years settings often wonder if what they’re doing for the EAL, GRT and BME children in their care is good practice, as inclusive of the needs of all children and their families as possible. Elsewhere, in settings that don’t have any children from these backgrounds – few and far between these days - work in this area is recognised as equally important. Yet it can be a challenge to find affordable guidance and training to help develop practitioners’ knowledge and understanding of their inclusion brief, without which they may not feel entirely confident when it comes to delivering fully inclusive practice in settings.

There are many questions practitioners might have about their contributions towards the diversity and inclusion agenda. For instance, what advice should they give families whose home language is not English? Should they tell them to carry on speaking their home language(s) to their child or swap to English instead? The answer to this one is that parents/carers should carry on using their strongest language with their child. It really doesn’t matter what that language is; young children can cope with more than one language from an early age and for parents to continue using the home language whilst their child gained exposure to English in an Early Years setting would be one way of raising a child bilingually (there are others). It is also the best way of ensuring that the child develops secure language skills whilst at the same time staying in touch with their cultural and linguistic identity.

For some children, coming into an Early Years setting can bring

many new experiences they have to learn to manage. For GRT children used to an ordered,

uncluttered home environment, the setting might seem chaotic and overwhelming

with its bright colours, numerous toys and messy play. GRT children may have played outside a lot

and may therefore find being indoors sitting still at an activity very

challenging. The e-learning explains

this and other aspects of GRT cultures so that practitioners can grow their

understanding of how best to support GRT children attending their setting.

Other children may come with limited or no experience of being in an English-speaking environment. Accustomed to being spoken to in Urdu or Dari or Polish at home, this can be disconcerting and can result in some children becoming silent in the setting, especially at the beginning – which in turn can be a cause for concern to practitioners and parents alike. The e-learning will help staff better understand things like the ‘silent period’ as well as know what to do to support a child through it.

The term “Black and Minority Ethnic” is more comprehensive and generally encompasses a much broader sweep of children and families, not all of whom will speak another language or have lived in another country. The issues around diversity that staff in settings need to consider in relation to BME children may arise out of language differences, cultural differences, religious differences and/or differences relating to ethnic identity. Images on display in a setting should positively reflect diversity, especially so in settings where the majority population is white. Think also about the books used for story telling; do they include pictures of different kinds of families or of children of different ethnicities? Have you thought about choosing stories that don’t focus on pigs if you work with Muslim families? Or stories that reflect some of the home experiences of your GRT children? If this all seems a bit overwhelming, take heart; the e-learning will help guide you through the diversity maze and empower you to make some carefully considered choices when it comes to provision in your setting.

Towards a more holistic view of the unique child

Cultural and/or language barriers can mask what children are able to do, hiding their interests, skills, abilities and home experiences from staff in settings. Yet it’s really important that practitioners make efforts to find out what children bring with them to the setting. This can help staff better tailor provision so each child receives the best experience from their attendance.

Completing the e-learning will support practitioners to explore and understand what the features of a truly inclusive setting are. This will in turn help them develop their own practice so they give the best start to all their children.

Getting started

Try doing a learning walk around your setting with another member of staff. Ask yourselves if what you see reflects the diversity that exists in the wider world. Do the books you share with children include different languages and images of people from diverse backgrounds? Do you have cooking utensils from other cultural traditions in your home corner? What about the clothing in the dressing-up box?

If you’re not sure where to begin with a learning walk like this, the EMTAS Early Years e-learning can help. It presents guidance and information about a range of issues related to inclusion and diversity using images, short pieces of text and interactive activities like the one shown below.

Screen shot of an interactive activity from the Early Years e-learning module

Included in the module is a checklist practitioners can use to evaluate practice and provision in their setting. It will support you to develop an action plan appropriate to your own children, staff and setting, so any developmental work you undertake will be focused and meaningful, delivering positive change. It also signposts you to further sources of guidance and to resources you might use with children in your setting, many of which are free.

Contact EMTAS to discuss how to gain access to the Early

Years e-learning for staff in your setting.

The price varies according to the number of registrations you need.

Further reading/resources

Free guidance for EYFS from The Bell Foundation:

https://www.bell-foundation.org.uk/app/uploads/2019/01/Guiding-principles-for-EYFS.pdf

Food for thought plus signposting available from Entrust:

Reflecting

on Equality, Diversity and Inclusion in the Early Years | Entrust

(entrust-ed.co.uk)

Suppliers of multicultural books:

Multicultural

Diversity Children's Books - Letterbox Library

Mantra Lingua UK |

Dual language books and bilingual books and resources for bilingual children

and parents and for the multi-lingual classroom.

Free comprehensive guidance pack from Hampshire EMTAS:

Guidance

for Early Years/Year R settings | Hampshire County Council (hants.gov.uk)

Comments

By Chris Pim

In this 100th blog I take a Janusian look at the whole field of EAL, celebrating the significant progress that has been made over many years, as well as touching on a few worrying trends that might give cause for concern in the future. I hope that my thoughts will be received not so much as a ‘Swan Song’ but more as a conversation piece.

Over the last 25 years, as a specialist teacher advisor working in two local authorities, as an independent consultant and an author, I have seen many changes in policy and practice with respect to children and families from BME backgrounds and those learning EAL. Changes which have broadly been for the better.

Most encouraging is the fact that the attainment of pupils learning EAL has improved enormously over time. Whilst there are still groups that continually under-attain, and results are not always consistent across the country, the gap in attainment between EAL learners and their non-EAL peers has continued to narrow throughout key stages and across virtually all subjects. It is likely that a generational change is partly responsible for these data. There is no doubt that research into English Language Learning in general is better articulated than in the past and findings have become much more effectively communicated through training and guidance materials; consequently, practitioners are more equipped to cater for the needs of EAL learners than before. Credit where credit is due, continuous funding from government for Local Authorities and schools has been a major factor in these successes, not-withstanding that the funding is no longer ring-fenced for EAL work and now comes directly to schools or is used to buy-back a central LA ethnic minority achievement service through a locally agreed formula.

In the past, EAL has been routinely conflated with SEN in the minds of practitioners, and pupils would often be grouped inappropriately with less able learners. Pupils learning EAL could be withdrawn from the mainstream classroom for lengthy and usually unnecessary interventions, were usually denied full access to the curriculum and were frequently offered cognitively undemanding work. This often resulted in lowered self-esteem and stagnant rates of progress for learners, not just in acquisition of English but also academic progress in all subjects. These practices have largely been eradicated in recent years and in fact rather than seeing EAL learners as language disabled, practitioners understand that in fact bi/multilingualism is an asset and that proficiency in first and other language can be used as a tool for wider learning. Indeed, in the most supportive schools EAL learners act as supportive buddies for newly arrived pupils, become language ambassadors or get trained through the nationally recognised Young Interpreter Scheme.

Practitioners now have a more grounded understanding of their EAL learners than before because schools conduct robust baseline assessments for them. Using one of a range of EAL assessment frameworks that have been developed in the last few years, practitioners can track Proficiency in English (PiE) in a granular way for all their EAL learners, rather than relying upon National curriculum levels for English which were never a good fit for looking at English language acquisition across the curriculum. The BELL Foundation’s EAL assessment framework, the one recommended for school use in Hampshire, is extremely well thought through. It is a formative tool that is expressed via a set of ‘can do’ statements on a 5-point scale from New to English through to Competent across the 4 strands of English.

All this is very encouraging, but there are clouds on the horizon. Currently there is a distinct absence of governmental narrative around EAL practice and provision. This lack of a national focus is reinforced by how infrequently EAL appears to be referenced in Ofsted reports and the recent removal of the person in post as the National Lead for EAL, ESOL and Gypsy, Roma and Travellers is worrying. For a while the DfE required all schools to report Proficiency in English (PiE) data for every EAL learner on roll. However, this is no longer required - why this is a retrograde step was effectively articulated by NALDIC in a June 2018 position statement.

It is also concerning how many LA ethnic minority achievement services across the country have been lost or become drastically reduced in size. Worrying amounts of digital book burning have also taken place in recent years around EAL pedagogy, for example due to a change in government in 2010. However, if you know where to look, superb guidance developed years ago through the National Strategies is still available eg via the National Archives.

Within this self-inflicted vacuum we must look to national organisations to take the lead and provide unequivocal and freely accessible materials and guidance. The BELL Foundation should be commended for their recent work in this area. It is worrying how much online material now sits behind paywalls, something which is perhaps a sign of the times. It is encouraging, however, to still find beacons of EAL excellence online, such as free learning materials provided by the Collaborative Learning Project. There are also open access materials available via some local authorities, such as EAL Highland and the Hampshire EMTAS guidance library, to name just two. The EAL-bilingual Google group is still a useful place for sharing good practice, although there is scope to develop this further as more of an altruistic, collaborative, forum rather than its increasing use as a marketplace for selling services.

There are a few well established companies producing brilliant tools and resources. Mantra Lingua, as an example, has decades long experience in working with EAL practitioners to produce bilingual materials, bespoke products and clever digital tools. Long may they continue to do so. There are other companies also producing credible, tried and tested tools and resources that are broadly EAL-friendly, such as TextHelp, Talking Products, Cricksoft and ScanningPens to name just a few.

However, I also have some concerns about the increasing numbers of individuals/companies crashing in upon the EAL market. At times it seems like the Wild West, where sales representatives canter into town plying their latest cure-all tonics to the unwary or those looking for a quick fix. Despite bold claims, in my opinion, some of these products are no more than costly pedagogical placebos and at worst have detrimental impact on the children they purport to help. It is incumbent on all of us to check the credibility of any research claims made about these products to ensure they are EAL-friendly, that their implementation fits best practice principles and that scarce money is not being wasted.

We know a lot about what works best for pupils learning EAL (a synthesis can be accessed via The EAL MESHGuide), but we need continued research in the area. Whatever we decide to do, I would suggest investing time in researching things we don’t know rather than things that we implicitly do know. A recent long-term piece of rigorous research by Steve Strand and Dr Ariel Lindorff, Department of Education, University of Oxford (see article by BELL Foundation) established that it can take a long time for young New to English learners to achieve Competency (on average, more than 6 years for children starting in reception). Whilst this research did quantify empirically some potential rates of progress for PiE as assessed on the BELL Foundation EAL assessment framework, this finding is unlikely to be a major surprise to most practitioners. Neither will be the revelation that PiE significantly impacts overall attainment for learners of EAL throughout all key stages. Really, who knew?

So, what should we be researching then? How do we know what is important to help shape future practice and provision? Asking practitioners working in real contexts would be a good start. This is precisely what researchers at Oxford Brookes University have started to do. Distilling research proposals from the wider community of EAL practitioners they have defined a list of 10 potential areas for future research. Number 1 on the list, for example: What is the impact of inclusion teaching vs pull out teaching for EAL learners? This seems like an interesting and timely area of study. Implicitly I have always believed that withdrawal provision for EAL learners is rarely as successful as high-quality teaching in mainstream classrooms. However, there has been little rigorous research in this area to back up my assumption. I shall be interested to see the results.

I would like to finally finish by thanking the many amazing pupils, parents and dedicated professionals I have had the pleasure to work with and which has sustained me in my lengthy career working in this field.

References

Setting

Research Priorities for English as an Additional Language: What do stakeholders

want from EAL research? Chalmers, H. 2021 (Oxford Brookes University)

Ofsted

removes one of the voices for EAL in the inspectorate. NALDIC journal blog.

Chalmers, H. 2021.

Excellence and Enjoyment: Learning

and teaching for bilingual children in the primary years, PNS, 2006.

DCSF

(2009) Ensuring the attainment of more advanced learners of English as an

additional language (EAL), Nottingham:DCSF

EAL MESHGuide, Coles, S., Flynn, N., Pim C.

Hampshire EMTAS Guidance Library

Collaborative Learning Project

The

Young Interpreter Scheme®

New

Report: Proficiency in English is central to understanding the educational

attainment of learners using EAL, but how long does it take to achieve, and

what support do these learners need? Blog article, BELL Foundation

EAL

Highland

Mantra

Lingua

The BELL Foundation

(EAL Programme)

The

BELL Foundation EAL Assessment Framework

EAL-Bilingual Google group

Withdrawal of English as an

Additional Language (EAL) proficiency data from the Schools Census returns,

NALDIC, 2018

Comments

By EMTAS Specialist Teacher Advisor Lisa Kalim